Urvashi Vaid

Urvashi Vaid, 2012. Credit: Photo by Jurek Wajdowicz, courtesy of the artist.

Urvashi Vaid, 2012. Credit: Photo by Jurek Wajdowicz, courtesy of the artist.

This episode has been made possible with support from the National LGBTQ Task Force, the country’s oldest national LGBTQ advocacy organization. Learn more about the Task Force at thetaskforce.org.

———

Episode Notes

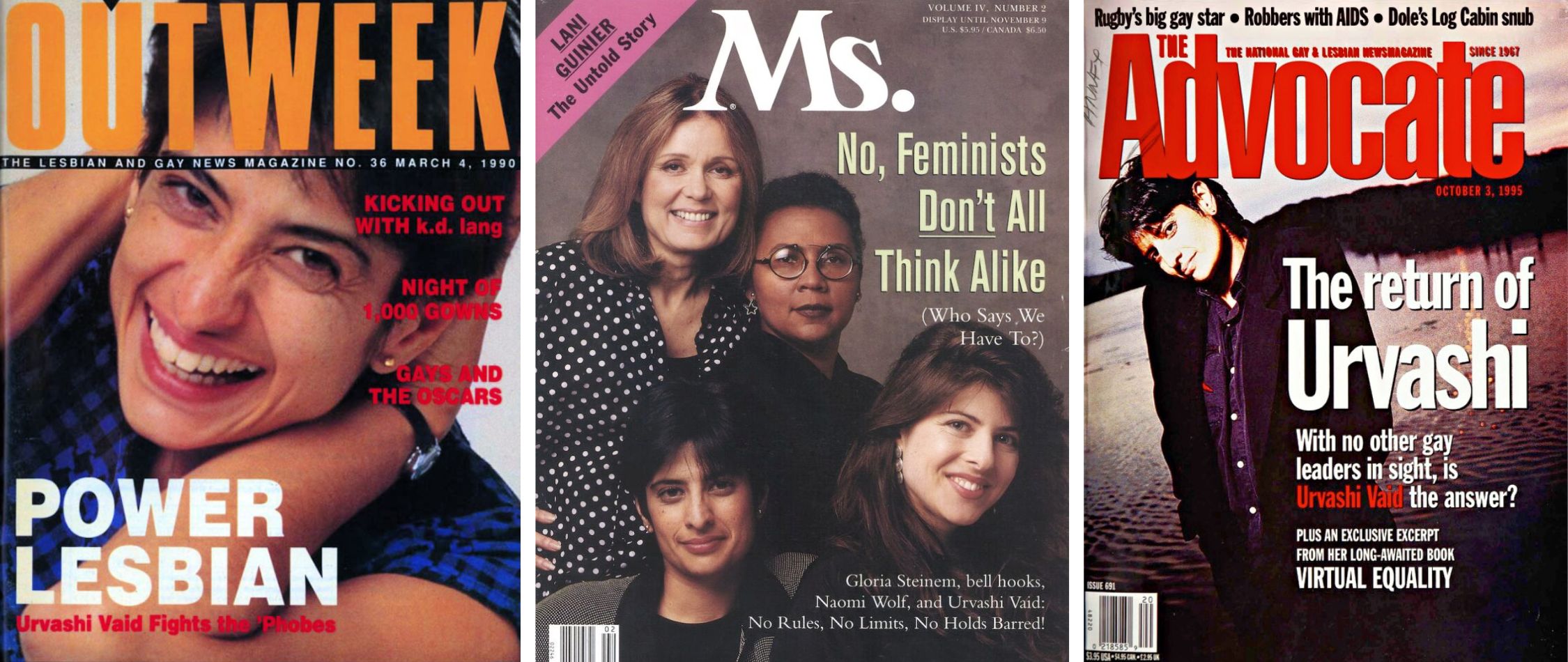

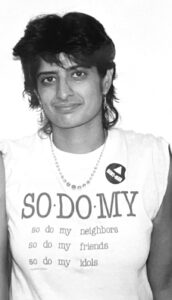

Indian-born activist and lawyer Urvashi Vaid was fiercely attuned to injustice from an early age. Adamant that the fight for LGBTQ equality cannot be separated from other progressive struggles, she became one of the most influential, outspoken, and inspiring movement leaders in recent history.

———

Learn more about Urvashi Vaid in this New Yorker profile by Masha Gessen, in her New York Times obituary, or on her website. At the top of the episode, Eric Marcus recounts his earliest memory of Vaid at a 1976 student protest at Vassar College; read his in memoriam piece about Vaid in the Vassar Quarterly here (Eric later corrected the piece in a letter to the editor to indicate that while Vaid participated in the protest, it had been organized by other students).

In the episode, Vaid describes the fraught relationship between straight feminists and lesbians in the second wave women’s liberation movement. In 1969, as leader of the National Organization for Women (NOW), Betty Friedan had accused lesbians of undermining the feminist movement, labeling them the “lavender menace,” and led the expulsion of lesbians from NOW. The following year, a group of women calling themselves the Lavender Menace (later, the Radicalesbians) staged a protest at the Second Congress to Unite Women and penned “The Woman Identified Woman,” a manifesto challenging sexism and homophobia within the movement. Read the manifesto and learn more here.

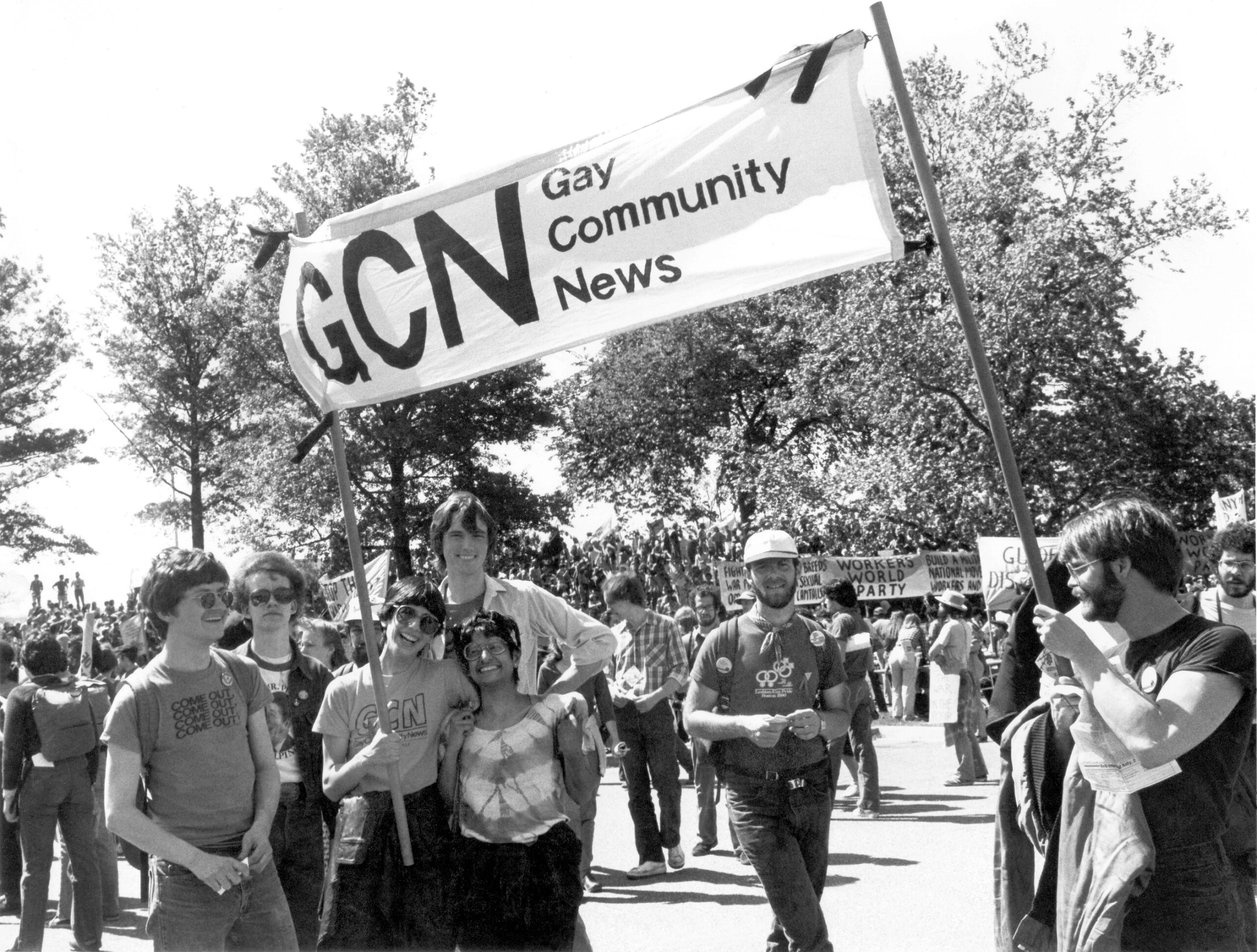

After college, Vaid attended law school at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts. Boston in the late 1970s and early 1980s was a hotbed of gay rights activism, and was home to the influential weekly newspaper Gay Community News (GCN), where Vaid worked and served on the board of directors. Read more about GCN, which was published from 1973 to 1992, here or watch this interview with its cofounder David Peterson. You can check out the paper’s very first issues and many others online. The GCN archives are kept at the Northeastern University Archives.

In the interview, Vaid mentions many of her GCN colleagues: Amy Hoffman, who wrote An Army of Ex-Lovers: My Life at the Gay Community News; activist Eric Rofes; institution builder Richard Burns; author and historian Michael Bronski; former longtime executive director of Lambda Legal, Kevin Cathcart; author Andrea Freud Loewenstein; author and professor Cindy Patton; Sue Hyde, who worked at the National LGBTQ Task Force for more than 30 years and cofounded the Creating Change Conference with Vaid; and GCN columnist Nancy Walker, who was featured in this MGH episode.

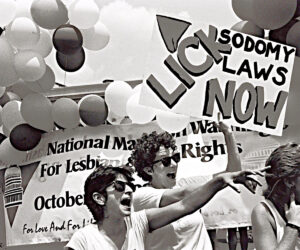

Vaid also describes a controversial 1981 GCN cover featuring “an incredibly anatomically correct drawing of a male penis … tied up with barbed wire”; you can see the graphic, not-safe-for-work image here. The cover was created in response to a virtually unprecedented move by Congress to veto a Washington, D.C., city council bill meant to legalize most sex acts between consenting adults. Learn more here. The District would not decriminalize sodomy for another 12 years.

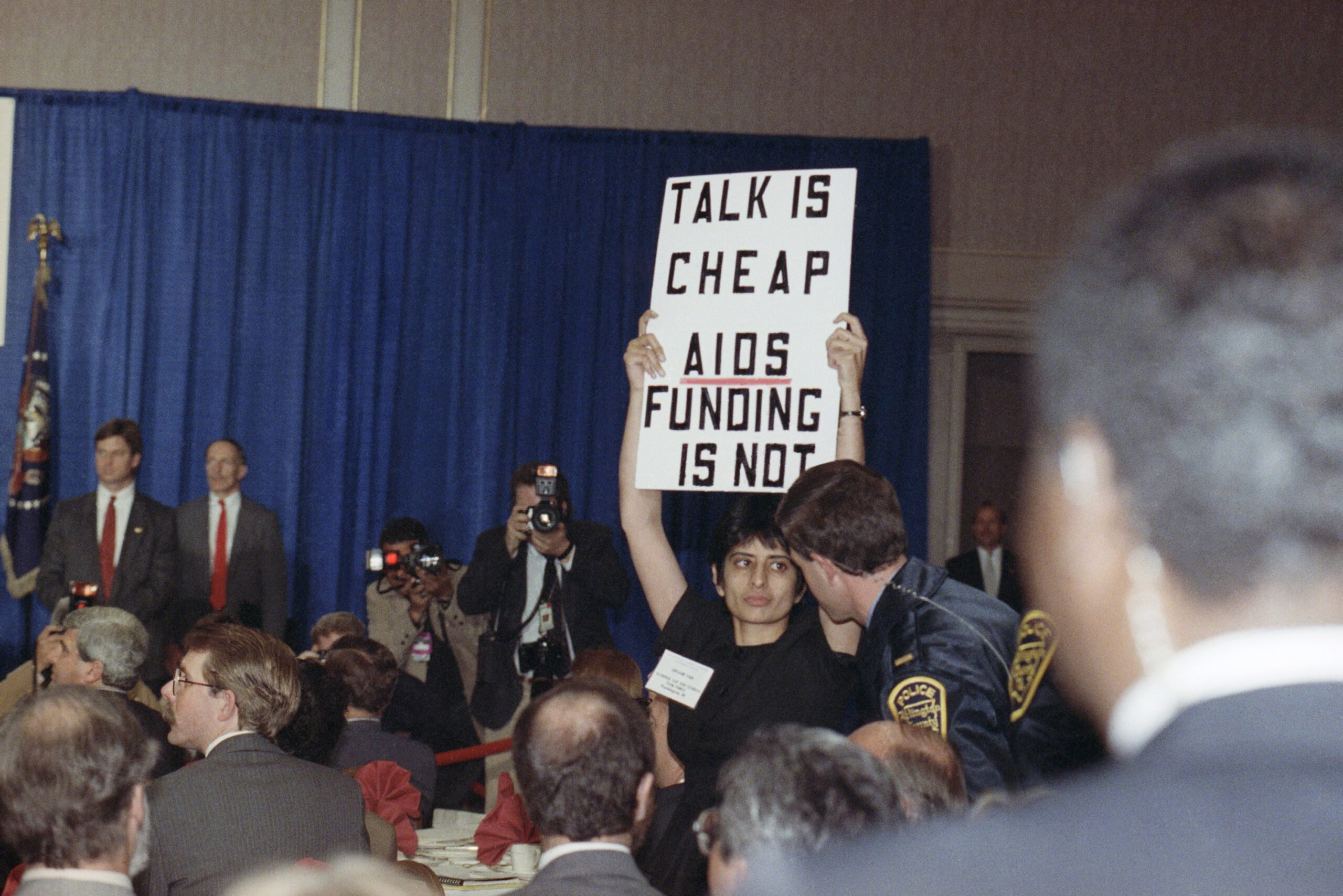

In 1990, while Vaid was executive director of NGLTF (the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, now the National LGBTQ Task Force), she famously interrupted President George H. W. Bush during a press conference while holding up a sign that read, “Talk Is Cheap, AIDS Funding Is Not.” Read the press release the NGLTF issued about the protest here. Vaid remained a public critic of Bush for his mishandling of the AIDS epidemic.

Vaid was a central organizer of the 1993 March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay, and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation. Watch footage of the march—including a snippet of Vaid’s speech starting at 10:03—here. To see Vaid’s speech in its entirety, go here. For reflections on the march’s significance, have a look at this photo essay, compiled on the occasion of the march’s 25th anniversary.

In her 1995 book, Virtual Equality: The Mainstreaming of Gay and Lesbian Liberation, Vaid criticized the movement for abandoning its radical roots in favor of assimilationist politics. In 2012, after more than 30 years of activism, she published Irresistible Revolution: Confronting Race, Class, and the Assumptions of LGBT Politics, in which she took the movement to task for being “co-opted by the very institutions it once sought to transform.” You can hear Vaid elaborate on these issues in this footage from the 2011 Dyke March in Boston.

Vaid died on May 14, 2022. She was survived by her longtime partner, political humorist Kate Clinton. Watch a joint interview with them from 1993 here, and one from 20 years later here. Vaid was aunt to gender nonconforming writer and performance artist Alok Vaid-Menon, who posted this tribute to Vaid. At Vaid’s funeral service, Patti Smith’s “People Have the Power” was played—a song that held deep meaning for Vaid. Give it a listen.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus: At Vassar, um, did you ever encounter any problems because you were lesbian-identified?

Urvashi Vaid: I think that I intimidated a lot of people. People stayed away and made assumptions about what I thought, or, “Oh, don’t even go to her with this one because she’ll just yell at you.” It always amazes me that people think of me as an intimidating person.

EM: Why?

UV: But I think… Because I don’t identify as that. You know, I’m short, I’m kind of scrawny and, uh, I think I should learn how to use it more to my advantage because I don’t, I don’t do it very effectively.

———

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

This episode is produced with the support of the National LGBTQ Task Force in honor of Urvashi Vaid, their one-time executive director, and one of the most dynamic, forceful, and visible leaders in the fight for LGBTQ rights and equity and social justice in recent history.

My earliest memory of Urvashi Vaid dates back to the fall of 1976. Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York. It was at a student protest—my very first. Vassar, a former women’s college that had gone co-ed in 1969, had put out a promotional brochure meant to attract male applicants. It managed to offend both male and female students and the campus was in an uproar. Urvashi and I were both 17. I was a freshman; Urvashi was already a sophomore. I still remember Urvashi’s commanding presence in the thick of the raucous demonstration, and her self-assured determination as she moved from the main protest outside into the admissions office for a sit-in: clearly not her first protest. I followed along quietly—no chanting for me—until I joined the sit-in, too.

It occurs to me that our different roles at that protest—Urvashi, out front and out loud, and me, following behind and mostly observing—hinted at the different paths we would take in life. Urvashi quickly moved into a national leadership role in what was then known as the lesbian and gay civil rights movement, and I stayed in the background, asked questions, and wrote about what I learned.

That’s how, at 31, we ended up sitting across from each other in December 1989. Me, recording oral histories for my book, she, the executive director of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, the country’s oldest national LGBTQ advocacy organization, which had been founded in 1973.

So here’s the scene. We’re at Urvashi’s Task Force office in Washington, D.C. I’m nervous about interviewing her. The fierceness that makes her such an effective voice in the movement is intimidating. But her easy laugh and the warmth and pride with which she talks about her family are disarming. Urvashi was born in 1958 in New Delhi, India, and moved to the U.S. when she was 8. With her parents and two sisters, she’d settled in upstate New York, where her father, a writer, had been hired as an English professor at SUNY Potsdam. I start by asking Urvashi about her early childhood.

———

EM: Interview with Ur-va-shi Vaid, Friday, December 15, 1989. Interviewer’s Eric Marcus. Location is the office of Ur-va-shi Vaid—or Ur-vashi Vaid?

UV: Ur-vashi.

EM: Is it Ur-vashi Vaid? Okay.

When did you realize you were different?

UV: You know, I always felt I was different all my life. Um, I think as a little girl in India, I did. Uh, and when I moved, when my family came to the States, um, I attributed that to being an Indian girl from an Indian, very Indian-identified family. You know, we ate Indian food at home. My mother wore saris. We spoke a mixture of Hindi, Punjabi, and English in the household. Um, I, when I came here, spoke with a fairly thick accent. I would often confuse v’s with w’s, as Indians do. “Vant”—I “vant” to do this.

Um, and I, so I, I think to some extent, my feeling of difference was about the cultural difference that, that, uh, was a big part of my—is a big part of my life. Um, but I, uh, I, I think, you know, as I grew older and, and through teen years, and, and, uh, college, that, that feeling persisted. And I always felt like an outsider and very questioning of the things as they were.

And my family also encouraged me and my sisters—I have two older sisters—to be very independent, and ideas had very great importance in my family. So you were encouraged to think for yourself and question everything—except of course parental authority.

EM: So over dinner you might have discussions about all sorts of issues.

UV: We had an incredible intellectual life in my family. My, my parents, um, pulled themselves out of poverty in India through education. And so their value was on education. Ever since I can remember, you know, the assumption was, you’re not only going to college, but you’re going to get some kind of graduate degree.

They just never believed in, in, uh, sex-role stereotyping in the sense of career, education, uh, being a force in the world. Um, but they were very traditional parents when it came to, um, everything like dating and, you know, expectations around, uh, being straight, uh, and having a family and raising children.

Both my sisters are married and have, are having kids and they’re married to Indian men, and my parents are very, very happy about that. And they still wonder why I can’t be, you know, “normal” in that sense, um, after all these years.

So to go back to your question about… Like, the debate around the table was, uh, fairly, uh—we were just encouraged to read and, and to talk about ideas and…

EM: What kinds of things might you talk about?

UV: Oh, like, D. H. Lawrence. A book.

EM: Really?

UV: I mean, I remember reading D. H. Lawrence when I was 10, you know? My father taught English literature. And so there were always books.

We might talk about—I remember vividly watching, uh, the conventions in ’69 and arguing about who was good and who wasn’t. Nobody in my family, I think, until I became a political activist, was a political activist. Yet, they were very aware of what was going on and had opinions about everything.

The war of course, the Vietnam War. I mean, I was a youngster when all the organizing and the rallying was happening. I mean, we’re the same age—we were 10 in ’68. And I remember marching in demonstrations, in Potsdam and I, I was just always, I, as long as I can remember, I have paid attention to what was going on in the world.

I mean, I would spend, I spent, while my friends were out playing, I was in libraries. I loved to go to the college library with my mother or father. Um, she worked as a librarian for a while and, you know, and I would just, like, read the card catalog and go to sections and browse and pull things out and read things. And, um, I can remember doing that at eight, nine, 10. Um…

EM: When did you get to the homosexual section in the card catalog?

UV: Oh, I did. I found the, the section on homosexuality at the Potsdam Public Library. I was probably 13 or 14. I remember reading, uh, just whatever was there, all these, a lot of clinical books, by, by MDs and studies by psychologists and, and doctors about homosexuality as a disorder. So I do remember going through that bookshelf.

EM: Were you looking specifically for it, or you just stumbled on it?

UV: I think I stumbled on it. I didn’t identify that I w—I didn’t know what my sexual orientation was. I guess my experience of coming to my sexual orientation was that I really thought about it when I saw openly gay people, and that’s when I got to college.

EM: What happened when you got to college?

UV: Uh, I got involved, I immediately got involved with student activism. I got to college in ’75 and the college was in transition. It had gone co-ed in ’69, but, you know, the large influxes of men were coming in in our class and the classes after that, so that was a big issue. There was issues about budget stuff, raising tuition, cutting back financial aid. Admissions policies were in flux.

From there I got really involved in the women’s, um, at Vassar also I got really involved in the women’s movement. I, I was really swept up emotionally by, by the, by the women’s movement. It changed my life, it did. Um, and I got real involved in the women’s center, which—we changed the name to the Feminist Union.

EM: When did the issue of, of lesbians come up within the Feminist Union or did it not? Because it was an issue within the women’s movement.

UV: Yeah. I mean, to be a feminist in the ’70s—and I think even to some people today—means to be lesbian. I mean, the word “feminist” became a slur, I think, in part because it was associated with lesbians. And what happened to lesbians in the women’s movement was very tragic. As I was entering college, the National Organization for Women was getting ready to purge lesbians from its leadership.

But in the second wave, um, a lot of lesbians were very, very involved in the creation of these women’s organizations, and started working on abortion issues, on violence against women issues. Um, you know, the network of rape crisis centers and battered women’s shelters did not exist before the women’s movement and organizers like me—I feel proud I was a part of that.

But anyway, I got involved with these groups and that’s when I met lesbians who were out, who were comfortable with their identity. And I was fascinated, you know, I had not met women who… I could identify with these women. I felt like, okay, this is the kind of model that I’ve been looking for. It was like a great recognition for me, personally, um, ’cause I’m not a conventional girl and I never felt like one. I never was into makeup or high heels or, or foofing up or… You know, I respect brains and, and action. And I’m a doer.

And, um, and I was, it was until I got to college that I met women that I could really identify with. So to me, it was like, I immediately was attracted to some people and I acted on the attraction and then it, then it was like—boom—it was, like, crystal clear to me. You know, I dated men, too…

EM: Was there conflict over that?

UV: Yeah, there was conflict. I didn’t know who I was and, and I don’t know, I think it’s that thing about behavior and identity. Like, if you asked me when I came to a lesbian identity, um, I would say that I don’t think I was a lesbian until I got out of college and moved to Boston and lived in a gay community. And that’s when I really knew: yeah, you know, I’m a lesbian.

In college it was much more of like, well, I dated women, I dated men, but I didn’t really have that big-picture connection. It was a very specific universe. It was Vassar college. It was just 2,000 people. It was this little petri dish—that’s what we called it—you know, where everybody was growing their own mold.

EM: It was, it was.

UV: It was! And, um, it was hard to have a—I don’t… So, yeah, so it’s hard for me to answer that question sometimes. And I was confused. I thought I was bisexual. Like, I had to have a label, right? I didn’t know what it would be, but, you know, by the end of college especially I sort of was like, well, I’m not really heterosexual, um…

EM: What am I?

UV: But I’m—am I homosexual? I mean, I, and I carried a lot of baggage about what it meant to be gay. Um, you know, I liked men. You know, I’m not a “man-hater.” Uh, and, and at the, at the time that I came into the women’s movement, there was all that stuff about separatism. And separatism was almost the thing that you did…

EM: Which meant what?

UV: … if you were a lesbian. Um, separatism means that you’re, you choose to direct your primary energies, work, life, love, every creativity towards women if you’re a women’s separatist, or towards men if you’re a male separatist. And I think our, our communities, the gay men’s community and the lesbian community in many ways are still very sexually separate and separatist communities. Um, not as a conscious ideology, but I think de facto our communities are very separate. And I think, you know, I don’t like that.

One of the things I miss the most about Boston, for example, from my years in Boston, is that Boston was an incredibly mixed gender movement. There were men and women working together in every organization that I worked in. I mean at institutions like, um, GCN.

EM: Gay Community News.

UV: Gay Community News, which is a national news weekly published out of Boston since 1973. Um, a bunch of men left because they didn’t want to work with lesbians and they didn’t see why the paper had to cover reproductive issues and why it was going off in this other direction. And a bunch of women came in and left because it was too male and too patriarchal and, you know, not responsive to them as women.

And the people who were left were people like us. People like Amy Hoffman and Richard Burns and, um, Eric Rofes, and Cindy Patton, Sue Hyde, Kevin Cathcart, um, Nancy Walker, Michael Bronski, Andrea Freud Loewenstein, and a whole bunch of other people who really worked together to come up with what I think is a very exciting gay liberation politics.

It was a politics that said that for society to change to the point where gay people can live openly, freely without prejudice and discrimination and violence, that we would need to change systems like sexism, that we would need to change racism. It was a politics that said we should not run away from sexuality. We can’t avoid that issue and say, “Oh, we’re just like you.” We’re not just like them. We’re different people. We’re different, not just in our sexual behavior, but in our viewpoint. Our experience of being the outsiders, our experience of being the hated ones, the queers, gives us a certain perspective that makes us different from somebody who has never had to be outside of anything.

EM: Mm-hmm. How did you wind up at GCN? Was that before law school, after law school, during law school?

UV: Um, it was before and during, um, I moved to Boston with my best friend from college because we were both very involved in the women’s movement. And we wanted to work in a women’s community. And so we sat down and we said, well, what city?

New York was too crazy, you know, D.C. was too far away from our families and our lives. And Boston was a hotbed of, of, uh, publications and, and ideas. And community groups. And, and so we moved there. We founded a group house—a nice vegetarian lesbian household that belonged to the Boston Food Co-op.

And we did community organizing in my part of Boston, Allston-Brighton, around violence against women and community safety in general. And it was a—for Boston, it was one of the most diverse neighborhoods with a lot of immigrants from Southeast Asia, with a Black population, with students, with elderly people. It was a real mix for Boston.

EM: Did being South Asian help your work at all?

UV: Um, well, I think me—I have the ability because of, I’m not white and I’m not Black, that I… In some ways I feel like, as an Indian, I don’t threaten people or push the buttons immediately. And so I get a lot of access and acceptance from both communities or from, from all sorts of places.

EM: By the time you moved to Boston, had you come out to your family?

UV: No, because, um, I, as I said, I don’t think I really had an identity as a gay person until I’d been living in Boston for a little while. And, and it made me realize that it was possible to be gay for the rest of your life, not just in behavior, you know? And I developed more of a political consciousness about gay oppression in Boston than I had ever had in college.

You know, I, I used to read GCN, and I thought it was a great, exciting paper. Um, and I got involved by just showing up on Friday nights and helping stuff—they used to use volunteers, we still use volunteers to stuff the paper and to get it out to the subscribers, put the labels on… Very basic volunteer work. And I just kept going and, and through that, met people and became friends. And before I knew it, I was on the board of directors.

EM: From reading, uh, GCN, it, it sounds exciting and incredibly difficult because you, you didn’t all agree.

UV: A lot of our early discussions that I remember were around this, the tension of women and men working together to forge, uh, a mixed movement. It had not really happened. Um, the, I think the gay liberation throughout the ’70s was very, very male-led and, um, and lesbians went into the women’s movement. Well, in the late ’70s and into the ’80s, lesbians have been coming back into the mixed gay and lesbian movement. And it’s like, the rhetoric of being a mixed movement has to come into contact with the reality of sharing power with women.

And, you know, men, gay men are trained to be men in society, to be in charge, and then like everybody who—I mean, women have a hard time sharing power too, and men do, too. And so there were a lot of those kinds of issues.

EM: Any memorable meetings?

UV: So many.

EM: One or two. Issues that you were involved in where you felt you needed to argue strongly.

UV: Oh, one of the biggest, most contentious issues was, that I remember, was in 19—I think it was 1981, um, around, uh… It was a cover by an artist from Maine who did a drawing, um, to illustrate the… The D.C. sodomy law was overturned by the, w—was, uh—what do you call it—repealed by the District city council. And then Congress overturned the repeal. They reinstated the sodomy law.

But to illustrate that, this guy, this artist drew an incredibly anatomically correct drawing of a male penis, uh, tied up with barbed wire. It was the barbed wire cock cover, we called it. And, uh, and it was such a h—that was one of the… Visual—for a newspaper, you know, visual images are as hotly debated as what’s in, what’s in the words. And, and I remember women being in an uproar about, “Why is this, this, you know, graphic, uh, genitalia on the cover of a paper that seeks to serve lesbians, and you’re not going to get readership…” And, and, and, by the way, every time we had a, uh, uh, you know, cover, cover with women’s breasts on it, we would get irate letters from men saying, “What are you doing with this?” If we got an equal number of letters from the women as from the men, we always knew we were doing something right.

———

EM Narration: In Boston, Urvashi thought of herself as a street activist and community organizer, focused on making a difference at the neighborhood and city level. But when the AIDS crisis hit, it threw into stark relief the challenges facing the gay community. Challenges that required a broader, national approach and that further crystalized her belief that the fight for lesbian and gay rights was closely entwined with other progressive struggles. That included the issue of abortion. She was emphatic—and prescient—about why LGBTQ people should care about reproductive rights.

———

UV: For the longest time, the gay rights movement could not understand why reproductive freedom was a gay issue. And I think there are still many people… I get letters from members saying, “Well, why are you doing so much on this issue,” you know, “when there’s so many important gay issues that we need to tackle?”

Well, the reason it’s a gay issue is because a woman’s right to control her body free from state intervention, free from the intervention of the church, free for moral posturing—the, the autonomy, the, the reproductive and sexual autonomy of a woman’s life is the same kind of autonomy that we’re fighting for as gay people: the right to control our sexual and reproductive lives free from state intervention and free from church intervention.

It’s the same issue. And it’s not—and, and, and if you look at the legal cases, the—what we were trying to establish in the Hardwick case came from the reproductive cases. What we did was we tried to argue that the court has recognized the right to privacy in certain decisions, a right of the individual or of a family or of a couple to make a decision based on their own lives.

And that government does not have a r—role in regulating a certain sphere. They can’t tell you when to have a kid. They can’t tell you that you must have a kid. That’s the right to privacy. And nobody—it makes sense. It makes good sense. The problem is it’s not an enumerated right in the Constitution. It’s not like the Second Amendment: you can bear arms. ’Cause there is no thing, there’s no amendment that says you have a right to privacy in these areas.

But what the court had done historically was construct it from borrowing from other decisions, reading into certain language that is in the Constitution, saying that, “All powers not enumerated here are reserved to the individual or the states,” or, you know, and it created this right to privacy. And what we did in the Hardwick case was come to, into court at every level and argue that that right to privacy included or envisioned the right of adults to engage in private, consensual sex. And that the state, government, a government, has no role in regulating that conduct and those choices, but we lost.

EM: Unfortunately. Did you, have you ever gotten letters from, uh, from women who disagree with, with the reproductive rights view?

UV: No. I generally get them from men. Yeah, no, I mean, I think I, you know, I think people get confused about defending a woman’s right to an abortion and, and, between that and how they actually feel about abortion.

And I think there’s a lot of people in our community who have problems, morally or whatever, ethically, with abortions, and they may not choose them in their lives. But I think that our community has to recognize that we must defend a woman’s right to choose. It is the same right that we are arguing for for us as gay people.

EM: How then do you translate that into the work of an organization like NGLTF as executive director? How do you balance, um, the, the importance of, of fighting for reproductive rights against the other work of the organization?

UV: Right. I think at NGLTF we’re not just a single issue organization. We don’t, I don’t think anybody here on the staff or the board believes that the world, that, that gay lib—oppression will end with the passage of a gay rights bill, you know. Um, and we want to work—I think there’s a real, over the years in this organization, over the 16 years of it, um, we’ve grown in our vision of what… There are just some issues that we’ve now incorporated that are as much our issues as the feminist movement, for example.

And I think you can say that, um, reproductive choice is squarely on our agenda and it isn’t going to go away, I don’t think. I don’t see it in the next 10 years.

———

EM Narration: Urvashi Vaid served as executive director of the Task Force until 1992. She went on to work at the Ford Foundation and the charitable Arcus Foundation—the same foundation that, incidentally, provided the initial funding for the Making Gay History podcast. After Arcus, Urvashi served as a senior fellow at Columbia University’s law school before starting her own nonprofit consulting firm. Urvashi also launched a super PAC, called LPAC, to promote LGBTQ women in politics. But perhaps her most important legacy was cofounding the annual Creating Change Conference, which has trained generations of LGBTQ activists who have continued the work that Urvashi so passionately championed.

The last time I saw Urvashi was about a year ago during a Zoom call with fellow founding board members of the new American LGBTQ+ Museum in New York City. Urvashi was fully engaged in the conversation, but at one point apologized for getting up from her chair and moving around. She was going through another round of treatment for breast cancer and was uncomfortable sitting for long.

Urvashi Vaid died on May 14, 2022. She was 63 and was survived by her two sisters and her partner of 34 years, the comedian Kate Clinton.

The month after Urvashi’s death, Roe v. Wade was overturned in a highly controversial decision by the U.S. Supreme Court.

———

Many thanks to everyone who makes Making Gay History possible, including producer Inge De Taeye, audio engineer Cathleen Conte, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. Special thanks to our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham, and our founding production partner Jenna Weiss-Berman at Pineapple Street Studios. And thank you, as well, to the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division for their assistance with photos and other images. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

A very special thank-you to the National LGBTQ Task Force for underwriting this episode in honor of their former executive director. For more information about the Task Force and the organization’s mission, visit thetaskforce.org.

Season eleven of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation; Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS; the Calamus Foundation; Christopher Street Financial; Mary Cadagin and Lee Wilson; Louis Bradbury; David Quirolo; Andra and Irwin Press; Eric Lee; and the hundreds of other donors who help us bring LGBTQ history to life through the voices of the people who lived it, including Patrick Hinds and Steve Tipton. Thanks Patrick and Steve!

Head to makinggayhistory.com where you’ll find all our previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature. It’s also where you can see photos of Urvashi as a young girl and teenager, which her sister, Jyotsna Vaid, was kind enough to provide.

If you’ve already subscribed to our brand new Patreon channel, this week you’ll have access to video of my recent conversation with Jyotsna as she reflects on her late sister’s life and legacy. Not a Patreon subscriber yet? I hope you’ll consider signing up today. For a $5 a month donation, you’ll get previously unreleased bonus clips from my archive and new video interviews with a range of people I know you’ll enjoy meeting. Find out more about joining Making Gay History’s Patreon community at patreon.com/makinggayhistory or go to makinggayhistory.com and click on the Patreon link in the home page banner.

I’m Eric Marcus. So long, until next time.

###