Robert Bauman

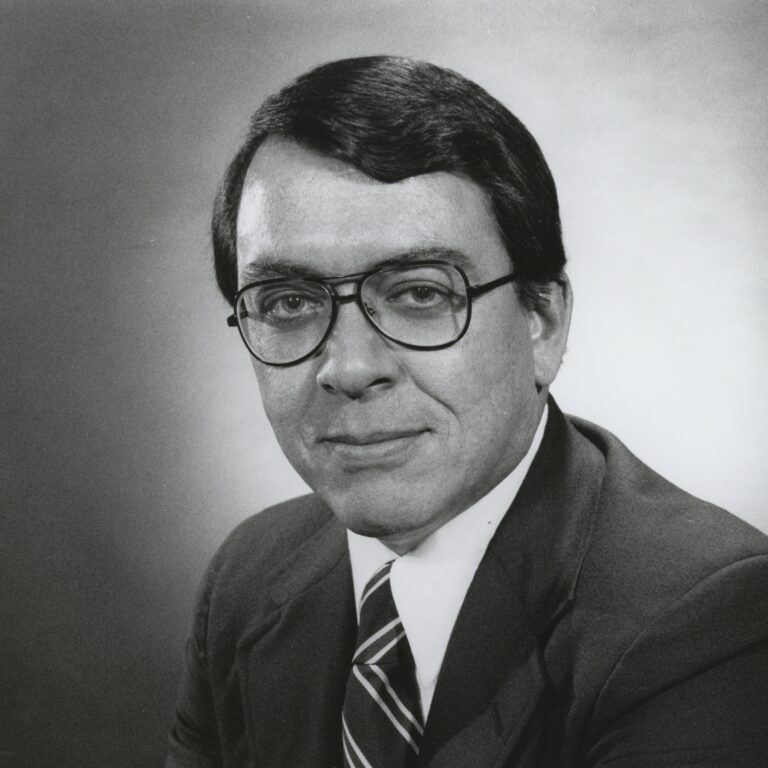

Congressional portrait of Robert Bauman, who served in the U.S. House of Representatives from August 21, 1973 to January 3, 1981. Credit: Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Congressional portrait of Robert Bauman, who served in the U.S. House of Representatives from August 21, 1973 to January 3, 1981. Credit: Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Episode Notes

In 1980, conservative congressman Robert Bauman was caught soliciting sex from a 16-year-old boy. The scandal landed the married father of four on the front page of newspapers across the country. It spelled the end of his political career—and the start of a years-long journey toward self-acceptance.

———

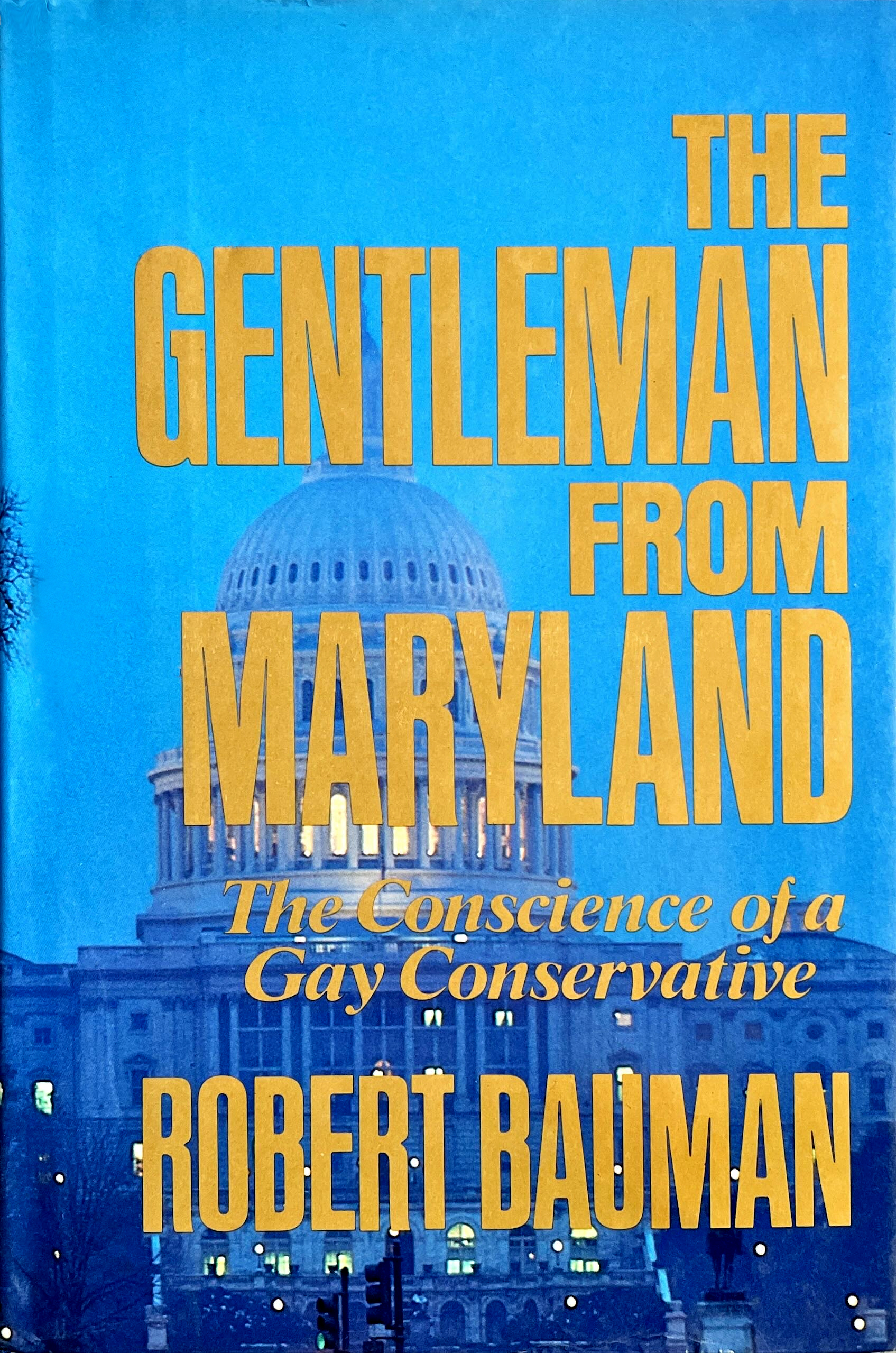

Learn more about Robert Bauman in this short congressional biography and this 2012 Washington Blade interview. Or have a look at his autobiography, The Gentleman from Maryland: The Conscience of a Gay Conservative, which was published in 1986; you can read a review here.

In the 1970s, Bauman was a rising star among conservative Republicans of the New Right. A 1976 New York Times article that Eric Marcus quotes from in the episode described Bauman as the “gadfly of the House, its most active nit-picker, its hairshirt, its leading baiter of its most powerful members”; read the article in its entirety here. He was a founder of conservative groups including Young Americans for Freedom and the American Conservative Union, and crusaded against a woman’s right to abortion, a procedure he publicly equated to murder.

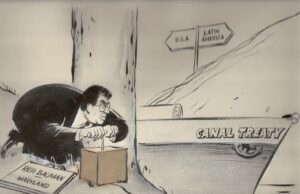

As representative of Maryland’s 1st congressional district, Bauman co-sponsored the Family Protection Act (an antecedent to today’s “Don’t Say Gay” laws), which sought to deny federal funds to any organization that presented “homosexuality as an acceptable alternative lifestyle” and allow businesses to fire employees for being gay.

In 1980, while seeking reelection, Bauman was charged by the FBI with soliciting sex from a teenaged boy. In a press conference, he attributed his actions to the “twin compulsions” of alcoholism and “homosexual tendencies.” He pleaded nolo contendere to the misdemeanor charge and entered a court-supervised rehabilitation program, but he did not drop out of the race, even when another man attempted to blackmail him. Bauman assured voters that he did “not believe the federal government should be in the position of supporting homosexuality.” He lost his bid for reelection, then tried to run again in 1982, but withdrew before the primary.

By 1983, Bauman had rebranded himself as an out gay conservative—a move not welcomed by all in the community. He was hired as a lobbyist by the Gay Rights National Lobby (which would later merge with the Human Rights Campaign) and argued before the American Bar Association against the kinds of legislation he’d once supported. You can read about his new role as an out gay public speaker here and listen to a speech he gave to the Concerned Republicans for Individual Rights (the precursor to the Log Cabin Republicans) here; he begins at 52:45.

In the mid-1980s, Bauman cofounded the short-lived Concerned Americans for Individual Rights (CAIR) with Leonard Matlovich (featured in this MGH episode) and other gay conservatives. Learn more about the group in this interview with CAIR spokespeople Jeff Snow and Bonnie McGinley, starting at 8:45. CAIR was formed in part to counter the virulently homophobic views espoused by Republican politicians like Senator Jesse Helms and Representative William Dannemeyer. However, as Bauman explained to Eric in 1989, the group “never got off the ground because we couldn’t get any gay Republicans to openly come out and do anything about it. They wouldn’t even write checks. They would give cash so there was no traceable evidence.”

To wit, one of CAIR’s secret cofounders, Terry Dolan—better known as the founder of the National Conservative Political Action Committee—died in 1986 publicly denying both his homosexuality and his AIDS diagnosis. That conflict was echoed in the two separate memorial services that were held after Dolan’s death: an official, closeted one, and one where his homosexuality was acknowledged. Bauman spoke at the latter. In 1990, Bauman debated Rep. Dannemeyer live on C-SPAN; you can watch the entire video here.

Bauman’s aforementioned 1986 autobiography, The Gentleman from Maryland, outed Massachusetts Congressman Barney Frank, who recalls the tense episode in this essay. Frank came out publicly the following year to much community acclaim. In his 1989 interview with Eric, Bauman maintained that he was under the impression that Frank was already out when he made mention of the Democrat’s sexual orientation in his book, saying “I don’t really think I dragged him out of the closet. I thought he was out of the closet; I thought the way I phrased it was simply an acknowledgement of a known condition.” In 1989, when Frank found himself the subject of a sex scandal of his own, Bauman wrote this op-ed in his defense.

In the episode, Bauman mentions two other gay congressmen: the closeted Stewart B. McKinney and Gerry Studds, who became the first openly gay member of Congress after his homosexuality was disclosed in a 1983 sex scandal. Washington, D.C., has a long history of gay sex scandals, rife with forced outings. Learn more in James Kirchick’s 2022 book Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington.

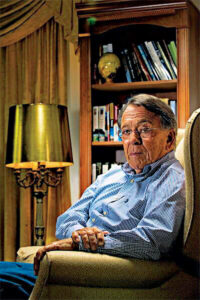

Since leaving politics, Bauman has written several books about offshore living and banking, as well as articles and reviews in a wide range of publications ranging from the Los Angeles Times to The Advocate. He lives in Wilton Manors, Florida, one of the gayest zip codes in the country.

———

Episode Transcript

Robert Bauman: I’ve had so many people say to me, uh, “How can you be gay and conservative? It’s impossible.” And of course they equate conservative with homophobia, with Jesse Helms, and so on, um, and, and I understand that attitude, but it’s, they’re wrong. Uh, and there are a lot of gay conservatives, not, not all of ‘em in the closet, but, uh, you can be, and it’s our fault for not coming out and having more courage to speak out. And I’m, I didn’t have to have much courage, ’cause I was yanked out, but, but, uh, it’s, it’s, it’s not, it’s not, uh, a contradiction in terms any more than it is to be liberal and gay.

———

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus, and this is Making Gay History.

When former Congressman Robert Bauman and I recently caught up on the past 30-plus years of his life in preparation for this episode, we discovered we both had the same question. What was he doing in my book? Among the 49 people whose oral histories I included in the original edition of Making Gay History, Bob Bauman is an anomaly. As he himself pointed out, “All these people that are heroes, and I’m a villain, so to speak.”

Unlike the other people I featured, Bauman did not earn a spot in my book through his involvement in the LGBTQ rights movement. But he did make gay history. In 1980, the Republican congressman was charged with soliciting sex from a 16-year-old boy in a splashy scandal that drew widespread media attention, not to mention plenty of liberal schadenfreude.

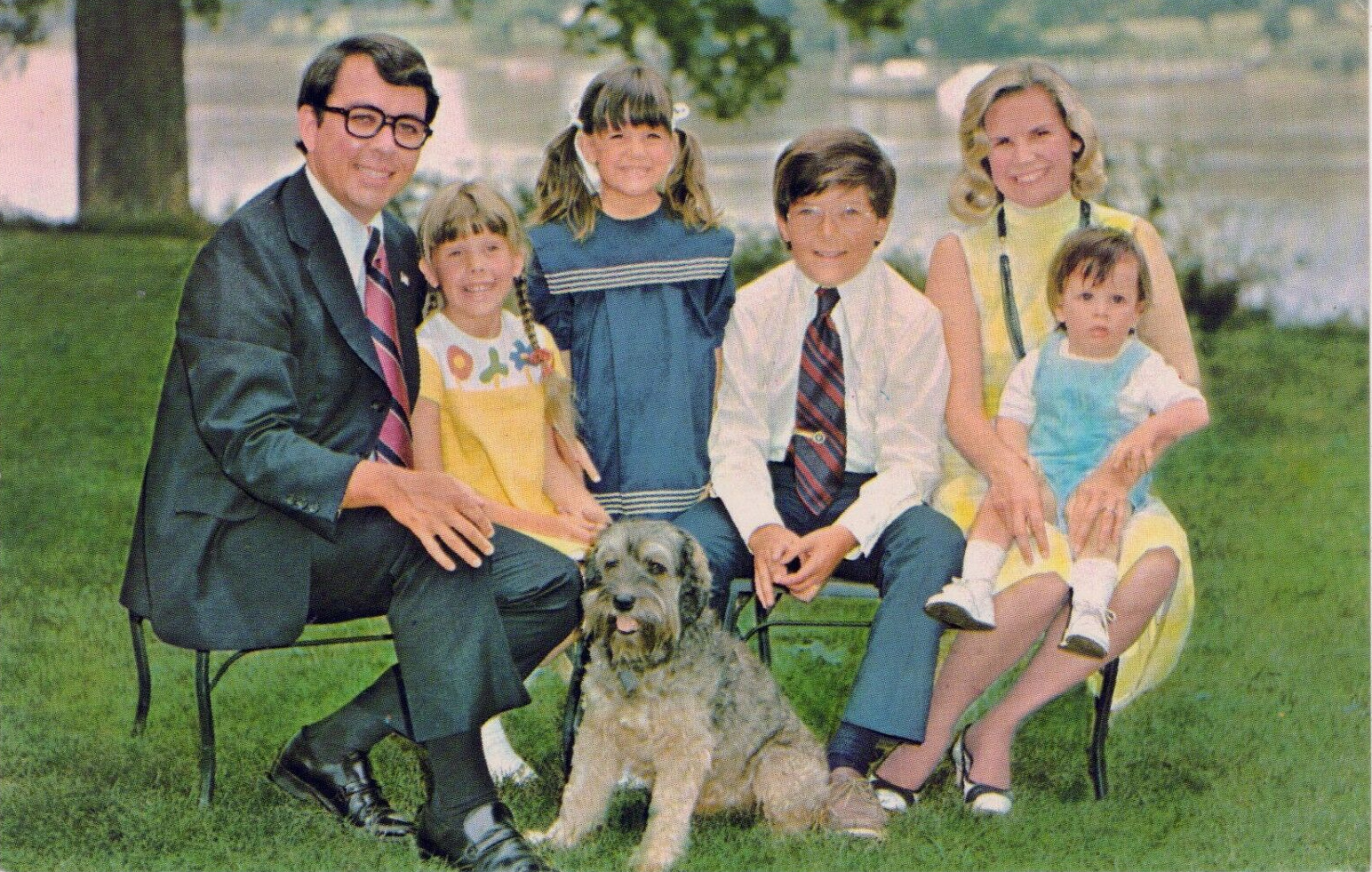

It was a stunning fall from grace for the 43-year-old right-wing conservative from Maryland. Since his election to the House of Representatives in 1973, Bauman had quickly risen to prominence as a savvy political player. He relished being a thorn in the side of the Democrats. A 1976 New York Times article described him as the “gadfly of the House, its most active nit-picker, its hairshirt, its leading baiter of its most powerful members.” And as a staunch proponent of traditional family values, the devout Catholic father of four was no friend to gay people or their quest for equal rights.

But as the scandal laid bare, Bauman had been living a double life. As he framed it at the time, he’d been brought down by the “twin compulsions” of alcoholism and “homosexual tendencies.” It seemed a classic tale of hypocrisy writ large, and I’m sure I was among those who thought that Bauman got what he deserved when his very public drubbing got him bounced out of office soon after.

So how did I come to include him in a book about the gay and lesbian civil rights movement? I’m not sure. But I do love a good story, and Bauman’s operatic downfall certainly had all the elements of one. Besides, in spite of the contempt I felt for who Congressman Bauman had been, he was still “one of us.” And I was impressed that after everything he’d been through, he was still standing.

Bauman was born in 1937 in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, to an unwed mother and adopted when he was six weeks old. His adoptive mother died when he was 8. And when his father remarried soon after, young Bob was sent off to military school in Virginia. If Bauman was a villain, he was a compelling one, even down to his origin story.

So here’s the scene: It’s mid-December 1989. With five minutes to spare, I show up at what I think is Bauman’s place in Washington, D.C. As it turns out, I’m off by about 20 blocks and have to race to the right address. I arrive ten minutes late—I hate being late. But Bauman is gracious as he welcomes me at the door, flanked by Ruthie and Patrick, his Jack Russell terriers. Bauman is a short, trim man with graying brown hair in a stylish cut—a more stylish cut than I expect to see on a conservative, I catch myself thinking. I’ve been warned that Bauman’s not a nice guy, but I like him right away. We chat amiably about my work as I set up in his living room and clip my microphone to his crew neck sweater. I press record.

———

Eric Marcus: Interview with former Congressman Robert Bauman, Saturday, December 16, 1989, at 2:00 p.m., at the home of Robert Bauman in Washington, D.C. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Tape one, side one.

Are the memories clear of that experience? What was a day like at school?

RB: A typical day there? Just a typical day at any military installation: wake up in the morning, you know, to a bugle, and march to, uh, breakfast, and march to class, and march to lunch, and march to gym, and march to dinner, and lights out, you know? It was, it’s pretty much regimented throughout.

EM: Did it strike you as at all odd, at all odd being sent away from home at that age?

RB: Uh, what struck me most of all was the, uh, the terrible, uh, feeling of homesickness. You just, you know, total debility. You couldn’t do anything. You just felt isolated, alone, and sad, and, uh, weeping a lot. Phone calls home, things like that.

EM: So you were on your own from a very early age?

RB: Yeah, I was on my own and I decided, if no one wanted me—’cause I took the experience as being a sort of rejection—if no one wanted me, then I would, uh, show the world. I’d do it on my own. I didn’t need anybody.

EM: Uh-huh.

RB: And I, three years of analysis 35 years later, uh, pretty well, uh, confirmed that I had followed that pattern to a T.

EM: Uh-huh. What sorts of things did you learn about boys growing up in that kind of environment?

RB: Well, I think that most of them were, as I was, essentially lonely. They came there usually because of discipline problems, but more often because their parents had no time for them or found them inconvenient.

I think most of them shared the feeling of rejection and, uh, a lack of self-worth. But I think it manifested itself in this sort of macho, uh, ac—uh, conduct where everyone tried to outdo the other and, and, uh, certain kids got sort of picked on. So it was a, it was a sort of, uh, brutal sort of, uh, system. But not unlike college hazing or high school or anything else.

EM: But it happened younger and—

RB: Much younger, at a time when kids are a lot more vulnerable and impressionable. I mean, you had a range from about 6 to 12, 13 years old. And, uh, there was a lot of homosexual activity. Uh, generally the, the rule was that, uh, it would be, it’s, it was alright to engage in these activities, which were usually initiated by someone else—you didn’t initiate them. I’m not sure how it ever happened if someone else was always, had to be, but the… And another rule was, unwritten, was that it was acceptable to do these things, but you, if you appeared to want to do them too much, you were too eager, you, you enjoyed them excessively, then you were queer.

EM: Mm-hmm. Did you participate?

RB: Oh, sure.

EM: Are you one of those kids who probably enjoyed it a little too much?

RB: Uh, no, I don’t think, uh, you can say that in a, in a, in a, uh, erotic sense I enjoyed it as much as I did the, uh, um, the closeness of another human being, the warmth of the embrace. Uh, the act of sex itself was not, was certainly pleasing momentarily, but I think it was the closeness, and that would probably fit together with the whole situation I found myself in.

EM: What was going on in the outside world? Were you aware of what was going on in the outside world at that time?

RB: Oh, I had an acute interest in public affairs. I was—1948 I was deeply, emotionally involved in the election. I was very much for, uh, Tom Dewey’s getting defeat—defeating Truman, heartbroken when, uh, when Truman won.

EM: What, what year did you identify yourself as a Republican?

RB: Um, was probably, uh, about a year before I went to military school. An aunt gave me a book about Lincoln called Abraham Lincoln’s World, and—my aunt Louise, my father’s sister—and I read it cover to cover twice. And I thought he was such a—well, I wouldn’t have used the phrase then—role model, but he was so pleasing to me as a human being that I became a Republican right then and there and vowed that I would be a lawyer and that I would go into politics.

EM: At the age of seven?

RB: Yes.

EM: You finished your, your eighth year at the military school.

RB: Yeah, I was there about, I guess, two full years. Maybe—I’m trying to think—it was two and a half years. Went to, uh, West Virginia, where my father had been transferred. And, uh, that’s when I, was the first time I really had to live with my stepmother, and I don’t think we were there a week together before it was total clash all the time. And, uh, I right then and there decided, how can I get out of this?

But, uh, one of my escapes was music, uh, in the form of the, the boys’—the children’s choir. A nun… I went to Catholic school and my, my, my, um, I was raised more or less an indifferent Methodist.

EM: A what?

RB: An indifferent Methodist.

EM: I thought for a second it was a denomination I…

RB: Yeah. Right. It sounds like it, doesn’t it? But, uh, I, I, I got involved in this Catholic, uh, choir scene, Gregorian chant, and the music and the liturgy, uh, literally entranced me. And, uh, I became a Catholic when I was, let’s see, when I was about 14, I think. And for a time there, I was greatly enamored of a young lady who was in my class, whom I, uh, who didn’t re—was unrequited love. And, uh, so I became a Catholic, fell in love.

EM: What appealed to you about Catholicism?

RB: Well, primarily my historic sense, uh, was that if the Church had been founded by the son of God, Jesus Christ, I ought to belong to it.

EM: Mm-hmm. Were there any teachings that troubled you?

RB: No. Anything that was taught was right.

EM: You must have learned the, the, the, Leviticus—

RB: No, that was much before people even talked about things like that.

EM: Uh-huh. Did you go away for high school?

RB: Oh, yes. I, um, well, I was, uh, in my sophomore year when I became a page, so I went three years to Capitol Page School.

EM: How did you even get the idea to, to become a page? Was…

RB: Well, my, uh, interest in politics did not abate, and, uh, in 1952, Eisenhower versus Stevenson, I was 14 years old—I guess 15 years old. We had moved back to Maryland. And, anyway, I was, got very active in the local campaign in, uh, in Easton, and formed a group of, uh, kids who rode around town on bikes—Bikes for Ike—giving out, uh… Although I was for Bob Taft for the nomination, I was not for Eisenhower, whom I considered an interloper.

But, anyway, it, uh, it drew—my activities drew attention to me on the part of, um, our local congressman. And I read in the New York Times, must have been December of ’52, that the Republicans, having taken over Congress, the House and Senate, that all of the patronage employees were to be fired and replaced by Republicans. And they said, “Including the pages, of which there are,” and they listed the number—it was like 50-some or something.

Light bulb went on. And I, I had an appointment at the dentist that I had to leave school to go to. And instead of going to the dentist, I went to—I, I called and arranged an appointment to see the local congressman, who was also from Easton.

EM: You just called him up?

RB: Yeah. I called his secretary.

EM: Oh.

RB: And, um… Well, Easton is not a big town. It’s only 7-8,000 people. And Ted Miller was the kind of congressman that you’d see on the street and say, “Hi, Ted.”

EM: Uh-huh.

RB: I didn’t know him, but I knew of him. So I went to see him and I told him I wanted to be a page. And he checked me out and said that, uh, people had given him good reports. And he said, “I’ll see what I can do.” And, um, I think I, I took office the day after Eisenhower did. I went to the Eisenhower inaugural as, as the congressman’s guest. And the next day I was, uh, raised my right hand and swore an oath of allegiance to the United States government, against all enemies, foreign and domestic. The first time I did that, of many times, and I was a page.

EM: That must have been a very exciting moment.

RB: Oh, it was indeed. It was indeed. Not only was I escaping from, uh, my domestic situation, but I was, I was right where I wanted to be. I mean, I was, I could walk 30 feet from the page bench out through the main door and stand where Abraham Lincoln had been a congressman.

EM: Was your stepmother glad to see you go?

RB: I don’t think it was, she was so glad to see me go. I mean, I think she was pleased that I was gonna be earning the princely sum of $450 a month, which in 1953 was quite a salary for anybody.

EM: Yes. Were you going to school at the same time you were a page?

RB: Yeah. They have a page school for, uh, pages, a high school that was part of the D.C. education system.

EM: You were an adolescent by then. Did you have an awareness of your attractions to men at that time?

RB: I was aware of those feelings certainly from the time I was in military school.

EM: Mm-hmm. Were you aware of what the rest of the world thought of it?

RB: No, not particularly. I knew what my immediate circle thought of it.

EM: Mm-hmm.

RB: It was, you know, well beyond anything Oscar Wilde ever described it as. Much lower, much more horrible.

EM: Mm-hmm. During the McCarthy era, this, this issue came up…

RB: But not so that I really noticed it.

EM: And you certainly didn’t connect your feelings with…

RB: No.

EM: … the perverts they were talking about, if, when…

RB: Well, I wasn’t gay. I wasn’t a homosexual. I mean, I, I was thoroughly convinced of that. I mean, it was a matter of, uh, building, uh, certain walls within your mind. And, uh, I couldn’t be one person like that. Not only had the Church told me about sin, and I assumed that, you know, anything like this was sinful. Although the Church never told me that directly, but I heard, I picked that up from my peers.

I mean, most of the attitudes about homosexuality are almost by osmosis in our society. Now they’re much more openly anti and, and also tolerance is much more open, but then it was just ingrained, inculcated by the, the, the wink of the eye, the, uh, the, the joke, the, the comment, the, uh, you know, “less-than-a-man”…

EM: Mm-hmm.

RB: So there were a lot of different things that operated giving me the opinion that that was something I sure wasn’t, thank God.

EM: Mm-hmm.

RB: But then I didn’t understand why I found the bodies of my fellow boys, my little boy friends attractive. It didn’t make much sense to me.

EM: Did you do anything about it?

RB: No. Other than what happened at military school. Besides, I had passionate, passionate love for this little girl in West Virginia that, uh, had come and gone.

EM: Mm-hmm. So that convinced you further that you were fine.

RB: I was okay. Yeah. Anything that happened was “a phase”…

EM: Right, right.

RB: … as we say, in the community.

EM: You got married.

RB: Hmm. Yep.

EM: In what year?

RB: Uh, 1960. My wife and I were both, uh, had a great deal in common. We’re both Roman Catholic. Uh, we both had alcoholic fathers. Uh, we’re both, uh, very strong conservative, politically, both active in the Nixon campaign. She’d worked on the Hill. I worked on the Hill. I met her when she was president of the Young Republicans at the Catholic girls’ school here. I was president of the Young Republicans at Georgetown. Uh, we loved each other quite, uh, strongly, and, um, it was just a match made in heaven.

EM: But it also turned out that you both liked men.

RB: Yeah. That’s the way it turned out.

EM: When did the, the issue of, of homosexual rights enter your consciousness? Or when was it an issue for you politically?

RB: I don’t know. I suppose when I was in Congress I would get a certain number of letters, uh, in, uh, the mail about that.

EM: What kinds of letters did you get?

RB: The few that I got on the topic were, uh, generally supportive of gay rights and wanted me to, uh, support that view.

EM: How did you respond to that at that time?

RB: Uh, I had a very good legislative aide, who wrote a draft letter, um, to answer some of these. And it was a traditional and well, uh, stated Catholic viewpoint of homosexuality: that I didn’t condemn the individual, but I condemned the act. And, uh, that I was sorry, but I couldn’t support legislation that would enhance or give special status to, uh—the usual arguments—uh, to, uh, what essentially was perverse activity and sinful activity, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.

EM: Were you engaged in sinful activity at that time?

RB: Oh, yes. Sure.

EM: How did you reconcile that?

RB: Well, we, I didn’t feel I had to reconcile it, obviously. It was an unreconcilable dichotomy. Well, I was convinced that I wasn’t homosexual, but I knew I had a problem. And of course I drank to escape the, uh, obvious conflict. And of course, eventually, it led to, uh, um, my being confronted by my wife, my priest, and uh, and, uh, going into, um, therapy, and eventually into treatment for alcoholism.

EM: Too quick, too quick.

RB: No, but I, I say, that very conflict, which you so glibly threw off there as, “Well, how did you deal with it?” it took me, it has taken me now—let’s see, what time is it?—almost 10 years to deal with it.

EM: Right. How did she confront you?

RB: Uh, she found some, uh, uh, male magazines or something, which was not the first time. And it was just the last straw. I mean, she knew something was wrong for a long time.

EM: Mm-hmm. That must have been a nightmare for you.

RB: Well, it was a nightmare for her.

EM: Obviously. It must have been a nightmare for both of you.

RB: Yeah. We were married, oh, 20 years.

EM: Right. Um, was she fully aware of what, what that meant for the life you had together?

RB: I’m not sure. I can’t speak for, uh, what, what she was aware of at the time, but I think she was appropriately aware of her own survival. And, uh, she made the right decision, and that is to get the hell out and save herself.

EM: Mm-hmm.

RB: And she decided she was gonna separate from me and, and we were gonna—although she didn’t say so at the time, eventually it led to a divorce and even an annulment in the Church.

EM: Well, did she come home one day and say, and say, “I’m leaving.” Was that the confrontation?

RB: Well, no, no. The confrontation was, “You’ve gotta do something about this.” And the something that I did about it was to go sit down with a close friend of mine, Father John Harvey, and in a period of about two or three hours one evening when I was still in Congress, when there was no hint of scandal, everything was fine, except I was engaging in this conduct and I was drunk and I was…

So I went to Father Harvey. We had three hours, and he told me some months later, he said it was one of the most painful sessions he’d ever had, particularly when I told him towards the end and he asked me, “Have you ever told anyone about any of this?”… I was talking about everything we’re talking about today, and I was, what—this was 1980, so I was, uh, 42 years old—I’d never talked to anybody about it.

EM: Ever.

RB: Ever, ever. And I was telling him all these things and, um, and in fact, he put on his surplice at one point—a stole, uh, to hear confession. Uh, he said, you, “Should I consider this as a confession?” I said, “Sure. I, I would appreciate that.” And he gave me absolution. But be that as it may, so that was really the first time, uh, that’s how it was confronted. And so I, uh, December, January of 1979-80, um… I started going to a psychologist in February, uh, stopped drinking on May 1—the last drink I’ve ever had—uh, 1980.

And, uh, so when in September 1980 I learned that I had been under investigation for more than a year by the FBI, it was a total surprise to me. I mean, for, there were six months there where I was going through sort of a semi-euphoria thinking that I had gotten my life together. I was going to a shrink, I was gonna deal with this problem I had about sexuality, and Carol and I were gonna be happy and live ever after, and, and I wasn’t gonna drink anymore. And so, and so, and so on.

But at the time all this happened, a task force had been formed to look into the activities of a number of congressmen and senators, 12 or 13 of them. None of the others whom, who were being investigated or on whom they had information, no action was taken against any of them, including Studds, including, uh, Stewart McKinney, who later died of AIDS. Uh, and some who are still in Congress, actually. So, uh, this was a political decision.

EM: Why you?

RB: Why me? Because, uh—a number of reasons, um, not the least of which was probably a certain dash of hypocrisy—more than a dash. But the real reason was…

EM: Your own personal hypocrisy.

RB: Yes. But, but, but, really, uh, I was a threat. I had become in the House of Representatives which the press called the “watchdog” of the House. I had been on the staff there for years as a page and a, and a, and a legislative aide on the floor. And I used my knowledge of the rules to block all kinds of things that the Democrats wanted, including pay raises. And Tip O’Neill once said to me—uh, on the floor, he says, “I personally resent the gentleman from Maryland.” I said, “Mr. Speaker, no higher honor could come to me.” You know, something like…

I was a prick. And, uh, and so there were a lot of people who had—in fact, one nameless staffer was quoted in the Baltimore Sun when all this happened to me in ’80, saying, “It couldn’t have happened to a nicer guy,” you know? So…

EM: You were not liked.

RB: No. And, uh, but I was effective. And I really had caused a lot of political problems and so, you know, suddenly you see this son of a bitch, uh, uh, in and out of parking lots with, with the hustlers and gay bars and his license plate on the car, and he’s drunk, and it was a natural.

EM: How were you publicly exposed? How did that happen?

RB: Well, the, uh, Justice Department sent two FBI agents to my office in early September of 1980, uh, at that point a little less than eight weeks before the election, uh, and informed me of all this shit that they had dredged up, and that I had the choice, according to the U.S. Attorney Charles Ruff—uh, of course a Carter appointee—of, of pleading nolo contendere to a charge of solicitation for prostitution, a misdemeanor under the District law, or I would be charged with every felony they could and every other misdemeanor they could come up with, including, uh, uh, white slavery—you know, the old Mann Act applies in the District for transportation within the District for immoral purposes—uh, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.

So, you know, you become at that point, very, uh, illogical. And I really thought I could contain the situation. It was all thought of in terms of the election. And that was the most important thing. And, um, on October 3, I think it was, pleaded nolo. And of course it was, I was, the next two weeks were just frontpage every day, all over, not only in the Washington Post, but all over the world. And the press was so intrusive that we had to take the kids out of town for about a week.

EM: When you say intrusive…

RB: They were going to their school and trying to interview the kids. I mean, little kids, and, uh, their teachers and their friends. And, I mean, there were more television units on the streets of Easton than there were people. And, uh, it was crazy, it was absolute madness.

EM: What was that like sitting at home?

RB: The mind has a capacity to withdraw at times of extreme stress, at least mine does. It, it denies the reality of the situation and it says to itself, this can’t be happening to me. Don’t worry about it. It’ll be worked out some way or another. You just don’t wanna confront it. And eventually of course you have to, especially if you’re in the middle of an election campaign.

EM: So you—

RB: So I sat in the house for four or five days. Uh, Carol and I, we talked about it. We had a meeting of all our political leaders. They all came to the house and the consensus, without objection, from about 40-50 leaders from my district was, “Run—you look fine to us. Go out there and show ’em you’re the same old Bob Bauman.”

But, you know, the ultimate, uh, ultimately I lost the election by less than two percentage points, about 7-8,000 votes.

EM: Was that crushing?

RB: No, it was a relief, in one sense. Um, it was a relief because I just, it was like having a root canal every day, 24 hours a day. And suddenly it stopped. I needed the time to deal with, uh, a lot of issues inside and, and, uh, to, uh, try and achieve some serenity, which I’ve done.

Denial is a very, very strong, uh, emotion. I mean, when people have heard me say since, uh, “Well, I wasn’t gay until 1983,” and they’d say, “What, what the, what the hell are you talking about?” And I really mean it took two and a half, almost three years of religious and psychiatric counseling for me to one day look at a piece of paper that the Catholic Church sent me saying my marriage had been annulled. And they didn’t give reasons, but when I called the priest in charge of the, uh, Wilmington diocese and asked him, “What are the grounds?” he said, “Mistake of person.”

And so I had to get canon law. I had to get Father Harvey to call Catholic U. And, well, “Mistake of person,” he said, “it means that there could have been no, uh, proper union in marriage because Carol didn’t realize that you were incapable of marriage. And neither did you. You may not have, or you may have, but you were homosexual throughout this. You couldn’t have contracted a valid marriage.”

So I, it really was a mistake of person. I was one of the people who made the mistake. I didn’t know who I was. And, uh, when I looked at this paper, I said, “What am I fighting this for?” If the Church says I’m gay, the holy Roman Catholic Church, my Church says I’m gay, all right. Fine.

———

EM Narration: After Robert Bauman accepted his identity, he worked to support the movement in positive ways. That included testifying in 1983 before the American Bar Association to endorse legislation to ban discrimination against gay people. And he spoke at fundraisers for the Human Rights Campaign. But in the decades since I interviewed Bauman, he’s mostly kept a low profile. He’s traveled extensively and he’s written several books, as well as scores of articles and reviews in publications ranging from the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal to The Advocate. For the past twenty years he’s lived in Wilton Manors, Florida, one of the gayest cities per capita in the United States.

When the dust had settled on the scandal that yanked Bauman out of the closet and upended his family, his youngest daughter, Vicky, found a silver lining. She told her dad, “It’s a good thing this happened in one way because we would have never known who you were.”

Bauman, who is 85 years old, is close to his family, including his former wife, Carol, who also lives in Florida. In addition to their four children, they have nine grandchildren, and four great-grandchildren.

———

Thank you to Making Gay History’s hardworking crew, including producer Inge De Taeye, audio engineer Michael Bognar, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter.

Special thanks to our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham, and our founding production partner, Jenna Weiss-Berman at Pineapple Street Studios. And thank you to the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division for their assistance with photos and other images. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Season eleven of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation; Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS; the Calamus Foundation; Christopher Street Financial; Sam Freedman; Mary Cadagin and Lee Wilson; Louis Bradbury; David Quirolo; Andra and Irwin Press; Patrick Hinds and Steve Tipton; and Lauraberth Lima and Ariela Rothstein. Thanks, Laura and Ariela!

Head to makinggayhistory.com to see photos of Bob Bauman as a kid, with his family, and with Richard Nixon and a number of other U.S. presidents. On our website you can also find all our previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature.

And I invite you to join our new Patreon community, where $5 a month gets you access to exclusive new interviews and previously unreleased audio from the Making Gay History archive, and at the same time, you’ll be supporting Making Gay History’s mission. This week, we’re adding video of a recent catch-up conversation I had with Bob Bauman, as well as a bonus clip from my 1989 interview with him in which he tells a very surprising story about Harvey Milk.

Find out more and sign up at patreon.com/makinggayhistory or go to makinggayhistory.com and click on the Patreon link in our homepage banner.

I’m Eric Marcus. So long, until next time.

———

RB: I was invited by a prominent, conservative Republican senator who could have helped me immensely in getting a job with the government—the last 10 years have not been kind to me economically. And, uh, he invited me to lunch at the Senate dining room. And he said, uh, “I really think you should get back into government, it’s a shame Reagan doesn’t have your advice in, in some position.”

He said, “I do want to ask you a question before I do anything. What do you think about homosexuality as a sin?” And I said, I gave him the Catholic Church view about the nature of homosexuality, and that’s not a sin. And he said, “But what do you think about homosexual conduct?” And I said, “Well, I have to be honest with you, as someone who’s known you a long time, to tell you that I cannot believe that God would create a human being, uh, as he does me or any other homosexual, and then tell him that the rest of their life will be denied any right to intimacy or love with someone to whom they’re naturally attracted. I don’t think God, that is my kind of God.”

He says, “Well, then you, you don’t believe it’s sinful?” I said, “I think that’s probably what I just said.” He said, “Bob, I can’t help you.” I said, “I understand.”

EM: Do you understand?

RB: Yes, I understand it.

###