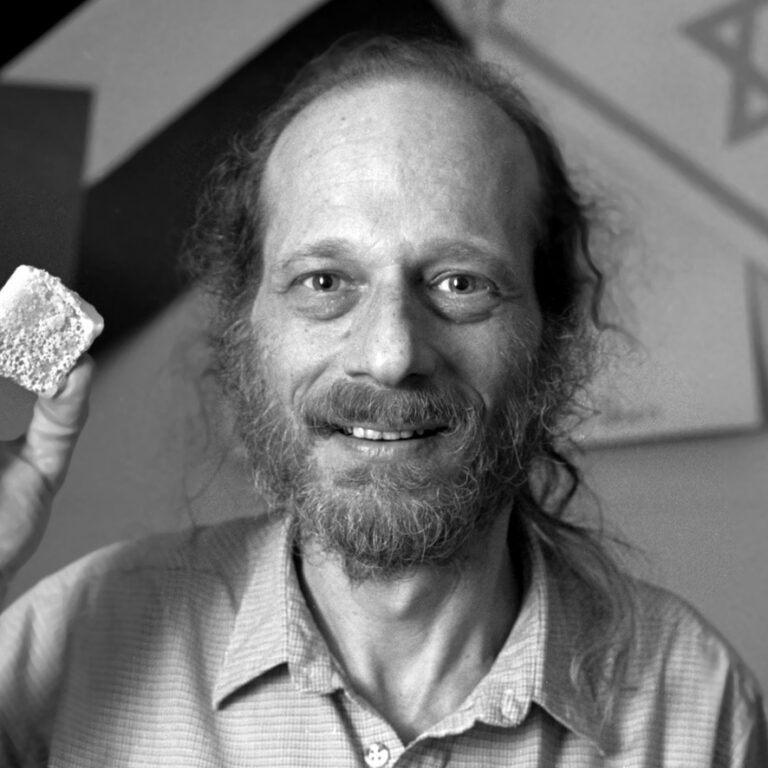

Faygele Ben-Miriam

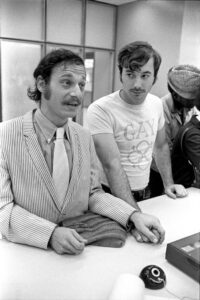

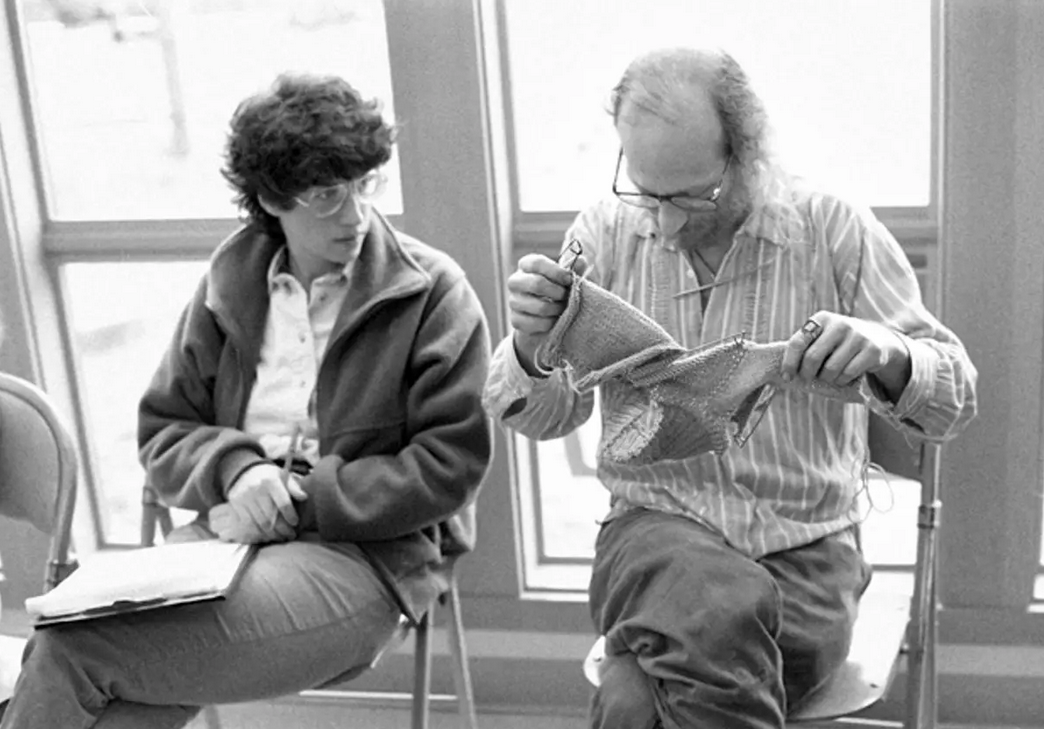

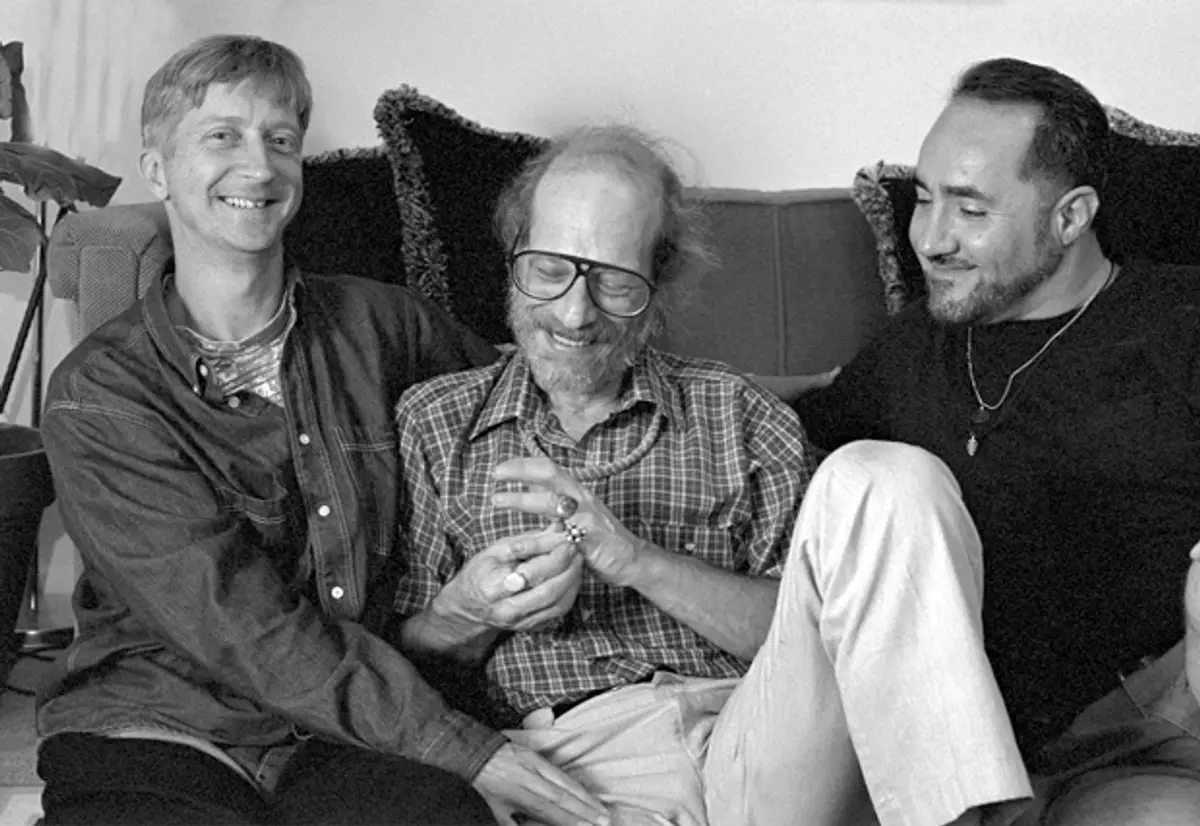

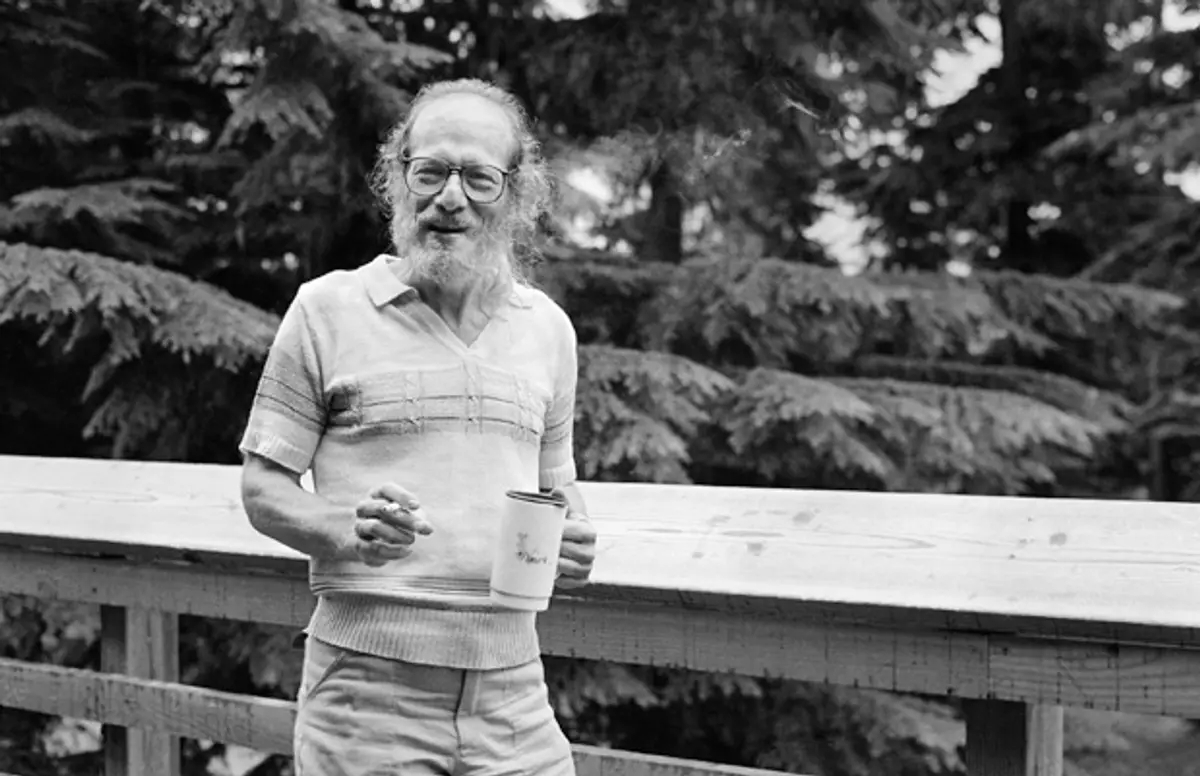

Faygele Ben-Miriam in an undated photo. Credit: Photo by Geoff Manasse, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections.

Faygele Ben-Miriam in an undated photo. Credit: Photo by Geoff Manasse, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections.Episode Notes

In 1972, Faygele Ben-Miriam’s penchant for wearing dresses to the office got him fired from his government job in Seattle. The fact that he had recently brought one of the very first same-sex marriage lawsuits was another strike against him. Undeterred, he went back to court and sued his employer.

———

Learn more about Faygele Ben-Miriam in this short bio or this in-depth Tablet magazine profile.

While studying at the City College of New York in 1969, Ben-Miriam joined the school’s gay student organization, Homosexuals Intransigent! (HI!). Read HI!’s newsletters here. To learn more about early LGBTQ student organizations, go here.

As a representative of HI!, Ben-Miriam took part in meetings of the Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations (check out the minutes of ERCHO’s spring 1968 meeting here); the North American Conference of Homophile Organizations (NACHO); the Christopher Street Liberation Day umbrella committee (click here to read their bulletins and reports); and the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA).

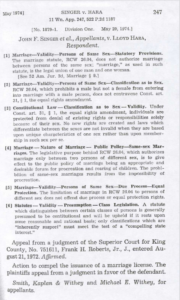

Ben-Miriam is best known for his use of the legal system to challenge anti-gay discrimination. On September 20, 1971, he and his friend and roommate Paul Barwick unsuccessfully applied for a marriage license at the King County Administration Building in Seattle. They sued, which earned them the distinction of being among the first same-sex couples to fight for the legal right to marry. Learn more about the case in this 2006 Seattle Times article, which features an interview with Barwick. Read the 1974 legal appeal here. For an overview of other early same-sex marriage cases, have a look at the paper “Glorious Precedents: When Gay Marriage Was Radical” by Michael Boucai.

The second pioneering legal case Ben-Miriam was involved in began in 1972, when Ben-Miriam was fired from his job at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) for “flaunting” his homosexuality. With the help of the American Civil Liberties Union, he sued for discrimination. The case made it all the way to the Supreme Court, which in a landmark 1977 decision overturned a lower court ruling that had upheld Ben-Miriam’s firing.

As a result of the case, the EEOC began enforcing prohibitions against discrimination on the basis of “sexual preference,” and Ben-Miriam was awarded back pay for the entire five-and-a-half-year span of the lawsuit. The case is notably absent from the EEOC’s timeline of LGBTQ workplace equality.

Ben-Miriam was actively involved in gay organizing efforts in his adopted hometown of Seattle. Learn more about LGBTQ activism in Seattle in this brief history or in Gary L. Atkins’s 2003 book, Gay Seattle: Stories of Exile and Belonging.

Ben-Miriam also helped produce the pioneering 1973 gay country music album, Lavender Country, by the band of the same name; listen to the track “I Can’t Shake the Stranger Out of You” here. Lavender Country’s frontman, Patrick Haggerty, was a friend of Ben-Miriam’s; in this recent NPR StoryCorps segment, you can hear Haggerty discuss Ben-Miriam’s legacy.

Lavender Country released their first new album in 49 years in February 2022. Haggerty died on October 31, 2022. Watch a short documentary about him here and read his New York Times obituary here.

In the mid-1970s Ben-Miriam helped develop the Elwha Land Project, an initiative by Gay Community Social Services, a Seattle nonprofit, to build a gay collectivist farm on the Olympic Peninsula. Ben-Miriam wrote about the project in RFD Magazine here. He then spent some time at the Wolf Creek Sanctuary in southern Oregon, a birthplace of the Radical Faeries, an inchoate movement originated by Harry Hay, who was one of the founders of the Mattachine Society and was featured in this MGH episode.

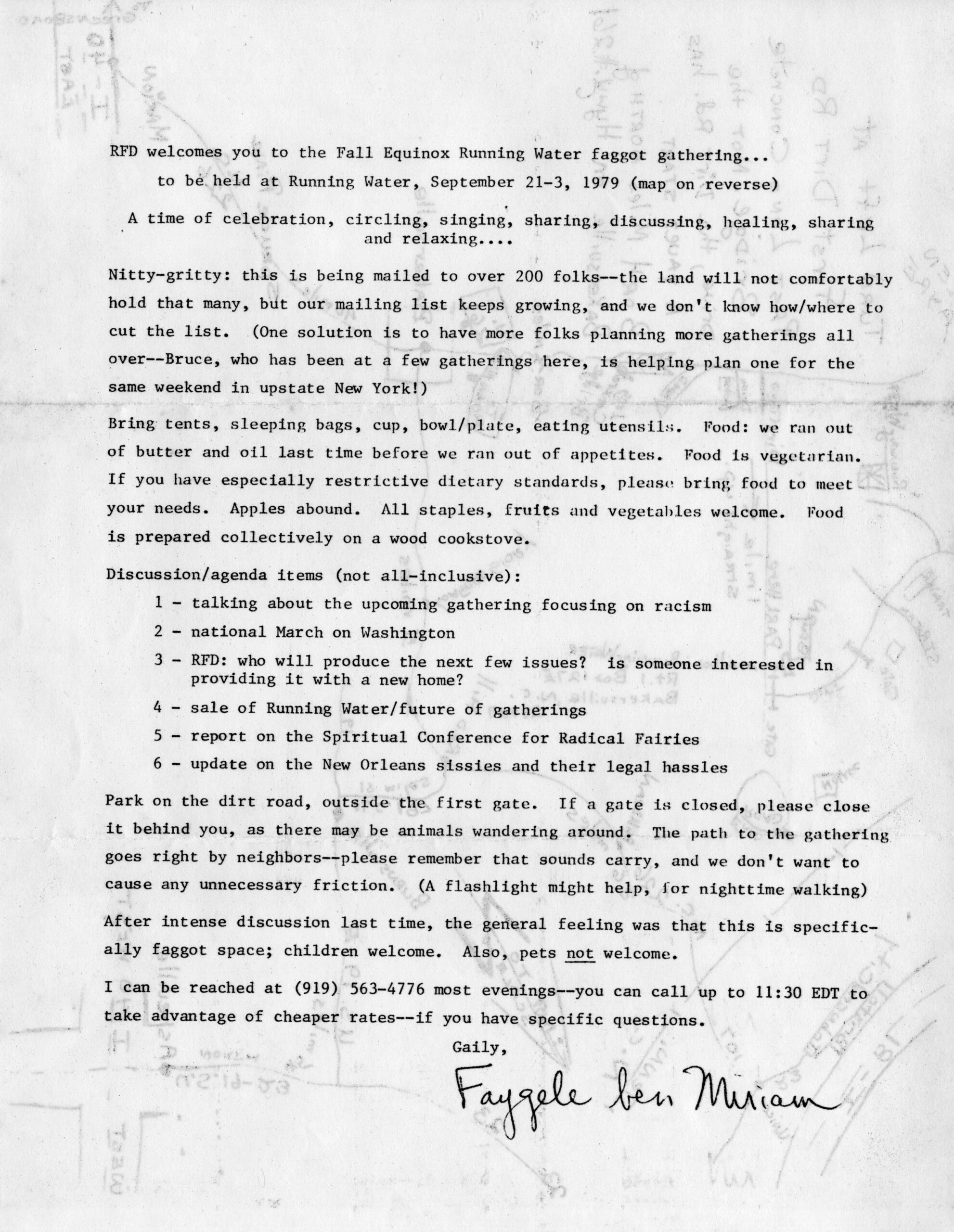

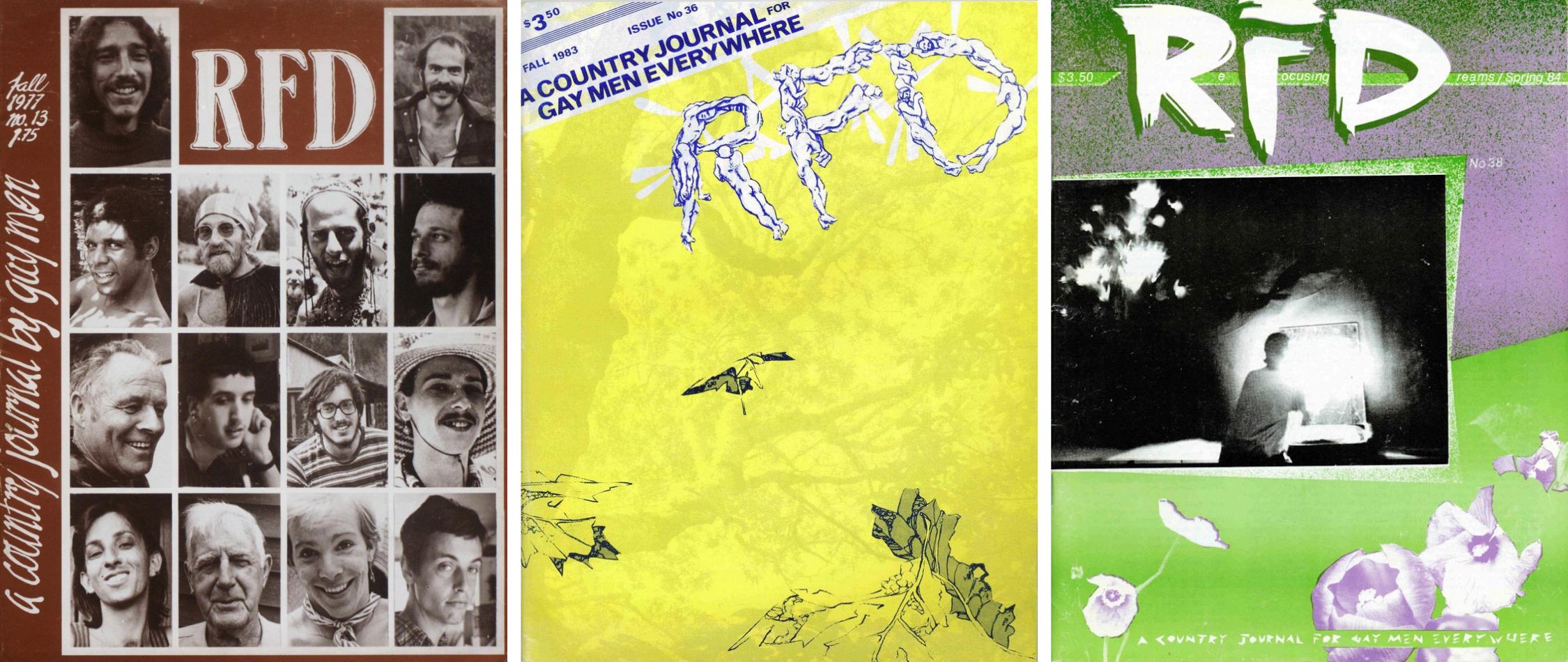

In 1975, Ben-Miriam became “keeper” of RFD Magazine, a publication for “rural fairies,” and moved its production to Running Water Farm in North Carolina, where he lived until 1984 before returning to Seattle. Explore RFD back issues here. This dissertation about gay liberation in the Carolinas references some of Ben-Miriam’s movement work during his time there.

Ben-Miriam’s activism extended beyond gay rights. He also served on the National Board of the New Jewish Agenda, worked with the International Jewish Peace Union, and was active in Kadima, which describes itself as “Seattle’s premier progressive Jewish Community.”

Ben-Miriam died on June 5, 2000, surrounded by family and friends. He was 55. His parting words, as reported in RFD, were, “Don’t mourn. Organize!”

———

Heads-up: In the interview, you’ll hear Faygele Ben-Miriam refer to intellectually disabled people using an outdated and now offensive term.

———

Episode Transcript

Faygele Ben-Miriam: I’m kind of bored with picket lines. I’ve been on picket lines since the ’60s. You know, there’s other ways to get a point across. I prefer guerrilla theater myself.

Eric Marcus: Any that you were involved in?

FBM: Oh, yeah. One of my favorites was, especially in the days I was wearing dre—it was around the days I was wearing dresses… Seattle had just started its tremendous expansion. There was lots of construction downtown and construction workers… Minis were in, in style then.

EM: Mini skirts?

FBM: Mini skirts, my favorite style. And these construction workers would whistle at women. And I would look back up at the construction worker and I’d whistle at them. And there were ways that, politically, I mean, this helped empower women and it also helped that these men could be made to see that this was indeed a two-way street.

EM: Did you get any comments back?

FBM: Oh yeah. They’d be pissed as hell.

———

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

Back in 1988, as I did research for the original edition of my Making Gay History book, one of the big themes that emerged was how gay and lesbian people used the legal system to challenge discrimination—including in the military, employment, child custody, and accommodations. To get advice on who could help me bring some of these cases to life, I called Tom Stoddard. Tom was the executive director of the Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, the nation’s first legal organization dedicated to achieving full equality for LGBTQ people.

Tom knew just the activist: Faygele Ben-Miriam, a transplanted New Yorker living in Seattle, who Tom called a one-person litigation team. Most famously, Faygele had sued the U.S. Civil Service Commission when he was fired from his government job in 1972 for “flaunting” his homosexuality. The year before, Faygele had also tested the limits of Washington State’s marriage statute, which didn’t explicitly state that marriage had to be between a man and a woman. Faygele and his friend Paul Barwick applied for a license to marry. When they were turned down, Faygele became the plaintiff in one of the first same-sex marriage lawsuits in U.S. history.

Faygele Ben-Miriam was born John Singer in 1944, the oldest of 4 children in a secular Jewish home. Leftist political engagement ran in the family. His mother, Miriam, in particular worked to advance a wide range of social justice causes, and ran a Planned Parenthood clinic. Faygele inherited his mother’s radical inclinations, and then some. Across the decades, he carried his zeal for organizing and gay community-building from the East Coast to the Pacific Northwest to the Southeast and back again. For a year and a half, he didn’t wear traditionally male clothing. And he was something of an uncredited spiritual father to the Radical Faeries movement, the gay anti-establishment group co-founded by Harry Hay of Mattachine Society fame. How could I not interview him?

So here’s the scene. I arrive at Faygele’s very modest house a mile and a half up the hill from downtown Seattle. Faygele’s not what I expect. He’s a slight, balding, rabbinical-looking guy in jeans and a well-worn sweater. He looks like an aging hippie from my old neighborhood back in Queens. I’ve been invited for dinner, and as I’m welcomed into Faygele’s home and introduced to his roommates, I’m enveloped by the aromas of what promises to be a delicious meal. Faygele’s a great cook, an even more accomplished baker. The dessert that’s baking in the oven even rates a rave in my post-interview notes: “Incredible,” I’ll later write.

We settle in at the dining table, where I get Faygele miked up. I start by asking him about his elementary school years on suburban Long Island.

———

EM: Interview with Faygele Ben-Miriam on Monday, November 20, 1989, at 6:00 p.m. at the home of Faygele Ben-Miriam in Seattle, Washington. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Tape one, side one.

Was Levittown unremarkable, your time there, or were you a troublemaker from the start?

FBM: Uh, I did a little bit of troublemaking there. It was during the, uh, Eisenhower years. The school prayer was instituted during that time, and the phrase “under God” was inserted into the Pledge [of Allegiance]. And our family fought that. I fought it as an elementary school student by not saying it, sitting down during the prayer.

And my mother politically fought, like, in the PTA and outside, fought that issue. So at one point one of the local Catholic churches was denouncing our, our family from the pulpit specifically as communists. And the neighbor kids that I used to play with, you know, all of a sudden were screaming “commie” at us across the street.

EM: You were just, you were, weren’t even a teenager yet.

FBM: Oh no. I was about eight or nine.

EM: Uh-huh.

FBM: Yeah, we started early. I come from a political family.

EM: Uh-huh.

FBM: We were, we were committed to equality, that it was, it was just and right. And along with that, that was part of being Jewish, was being involved in, in all of these struggles. Um, I was in a group that was working at integration in various ways. I traveled in an integrated crowd in high school, which used to anger some people, both Black and white, who were not happy with, with, with Blacks and whites hanging out together and socializing. Um, I was in a crowd that involved a lot—there was a lot of interracial dating going on, uh, where parents were just, you know, parents never knew about it. And if they did, there was hell to pay.

Even parents who believed in gen—one of the lawyers for the Scottsboro Boys, um, his daughter was in my crowd, and I remember their shock and horror when she was trying to date a Black man. She was white. She was Jewish.

Um, my job used to be, since I was so presentable, I used to pretend I was dating these, these women. And go pick them up Friday and Saturday night, couple of them, you know, sequentially, and get them out of the house, and then they could go off on their dates.

EM: With Black boyfriends.

FBM: Yes.

EM: Uh-huh. Why were you so presentable? Oh, because you’re a nice Jewish boy.

FBM: Yes.

EM: A nice Jewish gay boy, though.

FBM: Well, I wasn’t, um, I wasn’t—let’s see, if that was high school, I wasn’t out yet. I didn’t know that I was gay until I was 18, till my freshman year of college.

EM: Mm-hmm.

FBM: I came out in ’62. In October of ’62 was my first experience and also pretty much when I put it all together, that this is a viable option. Um, I didn’t spend a whole lot of time, uh, I didn’t waste much time, once I realized that it was a possibility that two men could have sex. And I was out to my friends throughout most of the ’60s, and even during being in the Army. My family by that time knew.

EM: Did you have any problem with your friends or family?

FBM: Uh, my mother’s position was, she didn’t think you could have a happy life and because she wanted me to have a happy life, and that’s why she was against it. And much later on, she was telling me one of the things that hit her was, my god, I’m not gonna have any grandchildren. I mean, she had three other kids, but you know, it was—she knew it was irrational.

My house was, uh, in, in a lot of ways, a sex-positive household and family. I mean, we were always allowed to bring home dates of the—it was assumed they would be of the opposite gender. My sister could do, you know, could do that, too. Um, it wasn’t just a boys-only thing, um…

EM: But what happened when your parents found out you were homosexual?

FBM: Well, I remember once bringing a boyfriend home, just on a—not for the night. And my father was very upset that I should have brought—he picked up right away that this was my boyfriend, not just a friend. And so my father definitely had, um, some problems coping with me during that time. Certainly after the movement started and as soon as I got active, he had, um… I think he’d come to terms with the fact that I was indeed gay and that was maybe all right, but then why go out there and announce it?

But given, given how we were raised to be political and stand up, it just seemed perfectly natural to me. And I mean, he, even, even to the end—’cause he’s dead now—uh, when I changed my name to Faygele and I sent a letter home, ’cause I was living in Seattle at the time. And it was a good letter, my mother reports, you know, an interesting one, ’cause I was doing lots of things, uh, mostly movement things. And he had enjoyed reading the letter and he got to the closing and saw “Faygele” and just took this letter and crumpled it up and threw it against the far wall. And so from that point on, I never signed a letter home. It was always “Love,” comma, “Me.”

I was adamant that… It was—he wouldn’t accept that name, but I wasn’t going back to the other.

EM: Why the name change? And for, for my, for the readers who don’t know what “faygele” means, can you define “faygele” for me.

FBM: Okay. “Faygele” is in Ashkenazic Jewish tradition a perfectly valid woman’s name that—in my grandparents’ generation, there were women named Birdie, which would’ve been the translation of that. Um, it also had the connotations among the older Yiddish-speaking people and first generation Americans who, when they wanted to refer to someone who was a faggot, but it wasn’t proper to say it—in the same way that you didn’t call someone “Black” or “Negro,” you always called them “schvartzes,” as if that made it nicer, that no one else would know what you were talking about—that “faygele” was the phrase for “faggot.” And so it seemed to me that since I was both adamantly Jewish, whatever that means, and adamantly gay, that I should have a name that refr—reflected both of my cultures.

And then after my father rejected my first name, I decided to reject his name, Singer. And since I’m also a product of my mother, then I took her name, and unlike many of the people who took their mother’s last name—which is simply their mother’s father’s name, which seemed to be, not be getting any place—I, in line with Jewish tradition, which is matrilineal to boot—in other words, we trace through our mothers, not our fathers, it doesn’t matter who the hell your father is… Um, “ben” is Hebrew for “son of,” and so I am “the faggot son of Miriam.” And my mother kind of gets off on that name. She does like it, when she, uh, got used to it all.

EM: Let’s go back now again, um…

FBM: … to the ’60s.

EM: You were drafted into the Army, you joined the Army, …? How did you wind up in the Army?

FBM: Combination of factors. The draft board was breathing down my neck, and part of it is, I wanted to prove that, um, it was possible to be gay and in the Army. And of course not say anything about it until after I came out. I mean, I had already rationalized that the question that they ask about, “Do you have homosexual tendencies?” is, no, I didn’t have tendencies. I mean, I, I was queer. So that I could answer their question and not feel compromised.

EM: Was that the question specifically?

FBM: Yeah.

EM: “Do you have homosexual tendencies?”

FBM: Mm-hmm.

EM: And you answered truthfully.

FBM: Yes, most definitely.

EM: Going into the military, you must have been frightened.

FBM: I was a little bit, but, you know, I—at some level I thought that I, people didn’t necessarily realize I was queer, you know. Over time I realized that that’s ridiculous. I mean, they have—listen to me, look at me, and how can they not figure it out?

EM: Mm-hmm.

FBM: But at the time I thought maybe I was sort of passing. It’s, it’s only when I hear a tape that I always have this reaction: “Is that me? I sound so faggy.” So, um… My speech teacher at City College, who—um, Mr. Reddish would say, “Mr. Singer, you need to learn how to lower your voice.” And he at that point, in front of the whole class, gave me a lesson. And I had to sing the lowest note I could, come up four steps from it. He said, “That is your natural speaking voice.” Anyway.

EM: Was it?

FBM: No, I’ve switched back to this one, whatever it is.

EM: So, so you’re dra—so you were drafted.

FBM: So I, I got drafted. I was a 1-A-O non-combatant, which meant I went in as a medic, which wouldn’t necessarily have stopped me from going to Vietnam—other non-combatant medics were sent there—but I was sent to Germany, and I did my two years there. Turns out I was in a, a setting with, um—I could, I was out to all of my friends. I was the major drug dealer on post, people had to deal with me whether they liked me or not. Um, I was well-liked by a lot of people. And my friends gave me a lot of support for being, for being gay, that I didn’t have to hide it.

In some ways it was a very nice environment. It was a family. We created a small collective within the military, a very un-militaristic group that did its best to fuck up the system every chance we could. I mean, medics were known to have the least shined of anyone’s shoes, things like that.

EM: When did you leave, um, the military?

FBM: Got out…

EM: Did you serve the full two years?

FBM: Yeah. Oh yeah. I’m now on 10 percent disability for psychological nervous condition. Um, I’m not quite sure exactly what the, the mumbo jumbo is around it, but it was traumatic being in an all-male environment. Um, and then being forced out of it. It just threw me for a couple of loops.

EM: Uh-huh. Okay.

FBM: Um, let’s see, I got out in June ’69, and moved back to New York. Actually, I moved in with my parents for a few months in Mount Vernon.

EM: June ’69 then… What good timing.

FBM: Well, I didn’t know about Stonewall. Um, I started back up at City College that summer. There at that point was already a gay group at City College called Homosexuals Intransigent, exclamation point. I immediately looked them up and joined. And through HI!—Homosexuals Intransigent!—I ended up going to some of the early planning meetings of the Christopher Street Liberation Day umbrella committee.

EM: Oh!

FBM: So I started dealing with the likes of Craig Rodwell and I got involved in, uh, ERCHO and NACHO—East Coast Regional Homophile Organizations and North American Conference of Homophile Organizations. Oh, I was also involved in GAA in New York. And then about March of 1970, I moved away.

EM: Why did you leave? These were exciting times.

FBM: Yeah, they were. Um, well, one thing—I had gotten held up going into my building in the East Village, not a pleasant feeling.

EM: Mm-hmm.

FBM: It was time to move on. I knew I was getting more and more political. Our family was around and we all had the same name. If they had a queer in the family doing this other politics, it would invalidate what they were doing. I mean, I wouldn’t have made that equation now. I, at that point, I didn’t want there to be a carryover from what I was doing affecting what they were doing.

So I got a van and I started—I left with this woman that I’d been sharing an apartment with, not a lover. And she wanted to go to Seattle and I kind of wanted to go to San Francisco. And we stopped in Detroit, picked up one of my Army friends. The two of them fell in love, became a couple, and they stayed in Seattle and I went to San Francisco, where I got a job with Bankers Mortgage Company.

I got that job in August of ’70. I was terminated in January of ’71. I was caught kissing a man in the elevator—my, I was saying goodbye to my boyfriend. Um, god knows what else. I mean, they were very uncomfortable having me.

EM: Because…?

FBM: ’Cause I was too open. I was too outrageous. I was too threatening.

EM: Mm-hmm. You left, then left San Francisco.

FBM: I lost my job. I couldn’t afford to stay there. I moved to Seattle. I moved in with the people I had come cross-country with. Went on unemployment, 32 whole dollars a week. Seattle had already had—it had a GLF here, it had a campus gay group, and it had a counseling service. Had a lesbian resource center.

We had a collective—uh, shortly after I moved here, we got a house, about ’71, and we ran a gay community center along collective lines. Uh, about that time I also—when my unemployment ran out, I got a job with EEOC.

EM: What is EEOC?

FBM: Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

EM: Doing what?

FBM: I was a secretary. It was interesting; my boss in the interview said, “This job, you not only have to have good skills, you have to have empathy for minorities.” And I said, “Well, I am a minority twice over. I’m Jewish and I’m gay.” And he was very impressed with that. And he said later that’s why he hired me.

About that time I discovered that—I discovered from Pete Francis himself, who was the senator who had introduced the state legislation about changing the definition of marriage. “Marriage is a contract between persons 18 years and older who,” and then they list various qualifications: you can’t be mentally retarded, you can’t… It never mentioned gender. And on Pete Francis’s part, that was very deliberate. And he wanted someone to test this.

So we talked at the household about it. I was into challenging it. Who we gonna do it…? There was one man in the house that I—we weren’t lovers, particularly, we were good friends. We had slept together—I mean, things were fluid in those days. Paul and I decided we’re gonna go down for a marriage license.

The clerk refused to issue a license. I mean, the TV cameras were there when we went to get the license. I mean, it was all quite, quite…

EM: You called a television station in advance.

FBM: Oh, yes. Yes. I mean, we had a lot of political expertise in this crowd. The local papers picked it up, the local TV stations, AP-UPI. Um, we got some interesting feedback, like letters from people in small-town Washington saying, you know, “I thought I was the only one.” And the news about a gay movement had never reached these people.

EM: Uh-huh.

FBM: The National Lawyers—we went to ACLU, would they be the lawyers in this case? ACLU wouldn’t take it. They said, “This is a little too frivolous for us to touch.” So, um—

EM: Marriage. This was too frivolous.

FBM: Well, let them stand on their own record. National Lawyers Guild—there was a collective in town. They took the case. Really wonderful people. Um, and we took that up through the second level, I guess, and lost, and decided we didn’t have the money or the energy… I mean, the National Lawyers Guild provided free legal help, but they needed money just for filing fees and stuff. In the meantime, we had the community center going. And so we dropped that case.

And then, as I said, I was working at EEOC, and all of a sudden we got hit up with this Civil Service Commission wanted me fired. The local Civil Service Commission office, which covered all local, you know, all hirings and firings, ultimately. And the list of charges that they drew up included such things as that I had applied for a marriage license and in doing so I—when the reporters asked me where I worked, I said “EEOC,” and their line of reasoning was that if known homosexuals were gonna be working for the government, it would cause people to lose their faith in the civil service system.

Um, and in the list of particulars, they listed, well, my van had things painted on it, like “Faggots Against Fascism,” and, uh, “Gay Power.” That I’d been caught kissing another man in the elevator at previous employment, all those kinds of things. Uh…

EM: So the issue here was, you were not just homosexual, you were “flaunting” it.

FBM: Yes, I was “flaunting” it and holding it up as a valid lifestyle. Um, I went back to the ACLU and I said, “Okay, is this now not frivolous enough? I’m losing my job.”

They had to take it. They did, um—they had a hell of a time finding a cooperating attorney who would take the case off and on. Um, I had about four attorneys in the course of the five and a half years that it took to fight the case. My coworkers signed a letter in defense of me that had absolutely no bearing. At one point EEOC had the choice of keeping me on during the appeal or firing me, and they chose to not keep me on.

Now, at that point, I had been wearing dresses to work. I was still getting excellent performance ratings. I wore the dresses—I mean, I spoke to this, this one woman who was my supervisor, a, a wonderful feminist. And I, one day I remember saying to her when I was working there, “Lynn, if we’ve been defending men with long hair and women wearing pants to work, shouldn’t that same law apply in reverse?” And she said, “Technically, yes, it would.” That you cannot make a dress code that applies to only one gender. And for the most part, my coworkers took it in stride.

The one outfit that crossed the boundary of outrageousness for them was, I borrowed a pair of black lace pants from, uh, a wonderful queen faggot in town. It had black lace underpants and a see-through sequined black top. Um, and so basically you could see skin where you shouldn’t see skin. And that one even my coworkers were a little bit upset about. The dresses didn’t bother them. And the truth be told, most of my friends tell me—and it’s probably true—that I had some of the tackiest outfits in town. It was the days of micro minis, um…

EM: So you wore micro minis.

FBM: I wore anything. I wore full-length gowns. I, I can show you some of the gowns—I still have them. Um, the difference between my wearing a micro mini and a woman wearing a micro mini is, I didn’t believe in underpants in those days—I don’t now, I didn’t then, I hadn’t for years—is that it’s very difficult to stay covered in a micro mini. It’s a real challenge.

EM: Why did you, why…?

FBM: Why did I wear dresses?

EM: Why did you wear dresses?

FBM: Um, I liked them. And I was experimenting. I mean, part of the things about being gay was the freedom to play around with and experiment with all kinds of things. And that was one of them. To see what it felt like to wear a dress. It was in some ways very liberating. In some ways it gave me an incredible insight, more than any other man around, of the vulnerability that women are up against constantly, especially when you’re wearing high heels. It’s very hard to run in high heels.

EM: Did you wear high heels?

FBM: Well, if, if it went with the outfit, yes.

EM: Uh-huh.

FBM: It was interesting ’cause a lot of the women, the feminists, the, the, the lesbian feminists that I knew, had a lot of trouble with drag. But I, and I also had a transsexual roommate, the two of us together, each from different perspectives, won over a lot of those women to being supportive of what we were doing.

EM: So you weren’t in drag.

FBM: That I wasn’t just, it wasn’t just drag, that it was a real political statement. And they understood that they couldn’t wear dresses because for them it was stereotypical behavior and they just couldn’t do it. I mean, those were the days when dykes had to wear bib overalls and have crew cuts, you know—the, the, the female clone look.

EM: Politically correct dress.

FBM: Yes. Yes. Um, there were other drag manifestations, but I was really the only one who took it to that extreme. I mean, for a year and a half I didn’t wear specifically male clothing. It gave me a picture of myself that I needed to see: that genital male that I am, that doesn’t define all of me. It lets me see sides of me that maybe after long analysis and long contemplation, I might have come to see. But it’s like a cram course.

———

EM Narration: Faygele Ben-Miriam eventually won his lawsuit against the U.S. Civil Service Commission. He was offered reinstatement at his old job and back pay and benefits to cover the five and half years during which his case made its way through the courts, all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court. The case helped lead to a new Civil Service Commission policy that federal employees could not be discriminated against based on “sexual preference.”

Faygele took the settlement but declined to take his old job back. He finished out his working life at the U.S. Department of Labor, where he worked as a secretary until his retirement in 1995.

He died five years later, on June 5, 2000. He was 55. His death was variously attributed to lung cancer, brain cancer, and HIV. His mother, Miriam, in whose honor he’d renamed himself, survived him.

———

Thank you to Making Gay History’s hardworking crew, including producer Inge De Taeye, audio engineer Cathleen Conte, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter.

Special thanks to our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham, and our founding production partner, Jenna Weiss-Berman at Pineapple Street Studios. And thank you to the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division for their assistance with photos and other images. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Season eleven of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation; Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS; the Calamus Foundation; Christopher Street Financial; Mary Cadagin and Lee Wilson; Louis Bradbury; David Quirolo; Lee Schere; Andra and Irwin Press; and Patrick Hinds and Steve Tipton.

Head to makinggayhistory.com where you’ll find all our previous episodes, archival photos—including of Faygele—full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature. That’s also where you can sign up for our newsletter so you’ll have the latest information on what we’re up to next.

And I invite you to join our new Patreon community, where $5 a month gets you access to exclusive new interviews and previously unreleased audio from the Making Gay History archive. This week, we’re adding a bonus clip from my interview with Faygele in which he makes a vigorous case for building community outside what he called the country’s “gay ghettos.”

Find out more and sign up at patreon.com/makinggayhistory or go to makinggayhistory.com and click on the Patreon link in our banner.

I’m Eric Marcus. So long, until next time.

###