Stella Rush (“Sten Russell”)

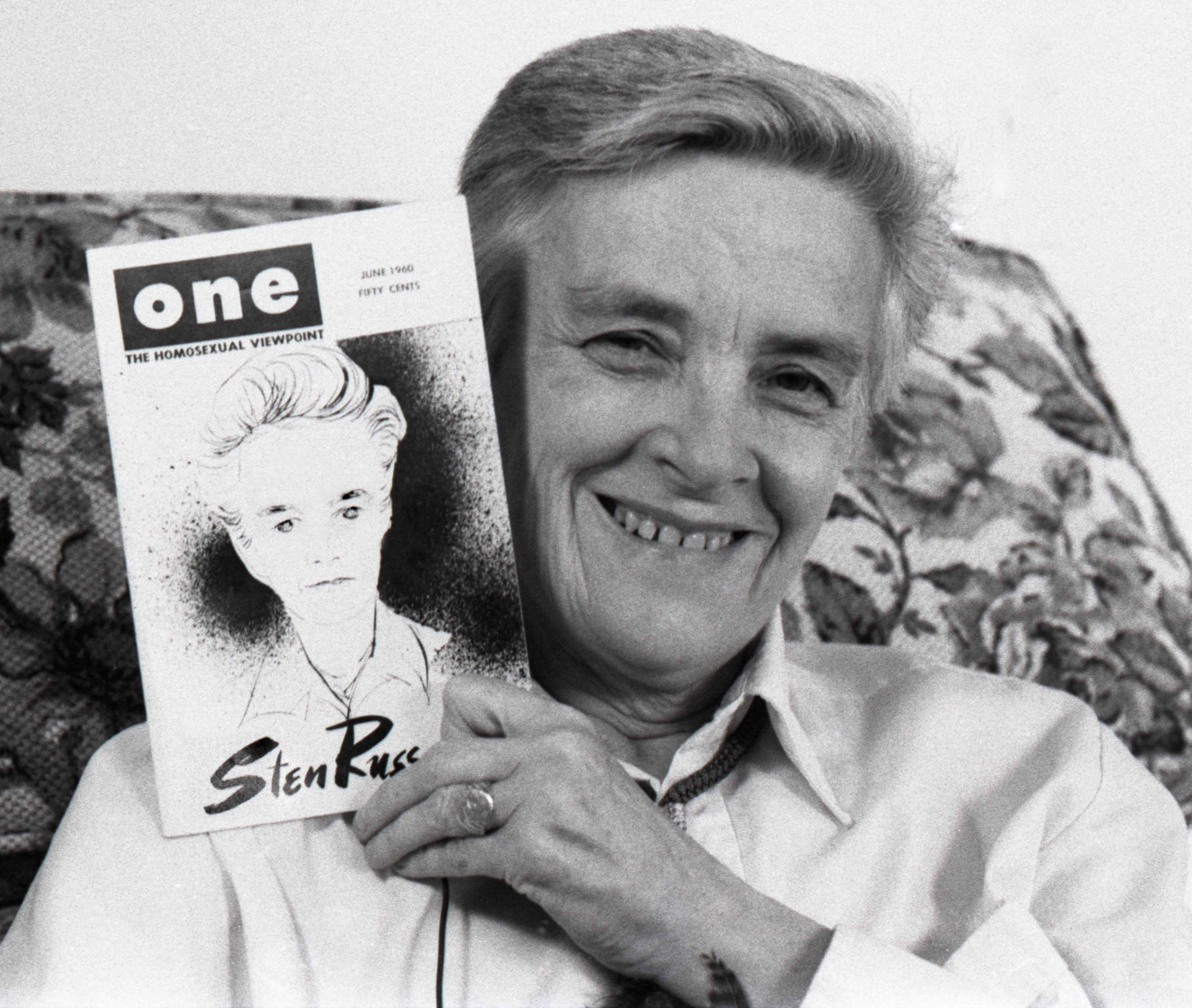

Stella Rush (aka Sten Russell) during taping for Lesbian Herstory Archives Daughters of Bilitis Video Project, San Francisco, May 15, 1987. Credit: Still from DOB Video Project, © Lesbian Herstory Archives DOB Video Project, LHEF, Inc.

Stella Rush (aka Sten Russell) during taping for Lesbian Herstory Archives Daughters of Bilitis Video Project, San Francisco, May 15, 1987. Credit: Still from DOB Video Project, © Lesbian Herstory Archives DOB Video Project, LHEF, Inc.Episode Notes

From Eric Marcus: When I sat down with Stella Rush in her landlord’s apartment to interview her in 1989 in Costa Mesa, California, I only knew the very broad outlines of her life—that she was born in Los Angeles on April 30, 1925, and was the only child of an only child. Her father died when she was two. She attended Berkeley for two years and then transferred to UCLA, but left after completing her junior year.

What interested me in Stella’s life was her work writing for ONE magazine, the first national gay magazine. The reason I wound up interviewing Stella in her landlord’s apartment was that Stella had three people living in her apartment and she was staying at a nearby motel. For some reason, I didn’t ask anything more about her living arrangements. Perhaps I felt it would be intrusive, although that usually didn’t stop me from at least asking the question.

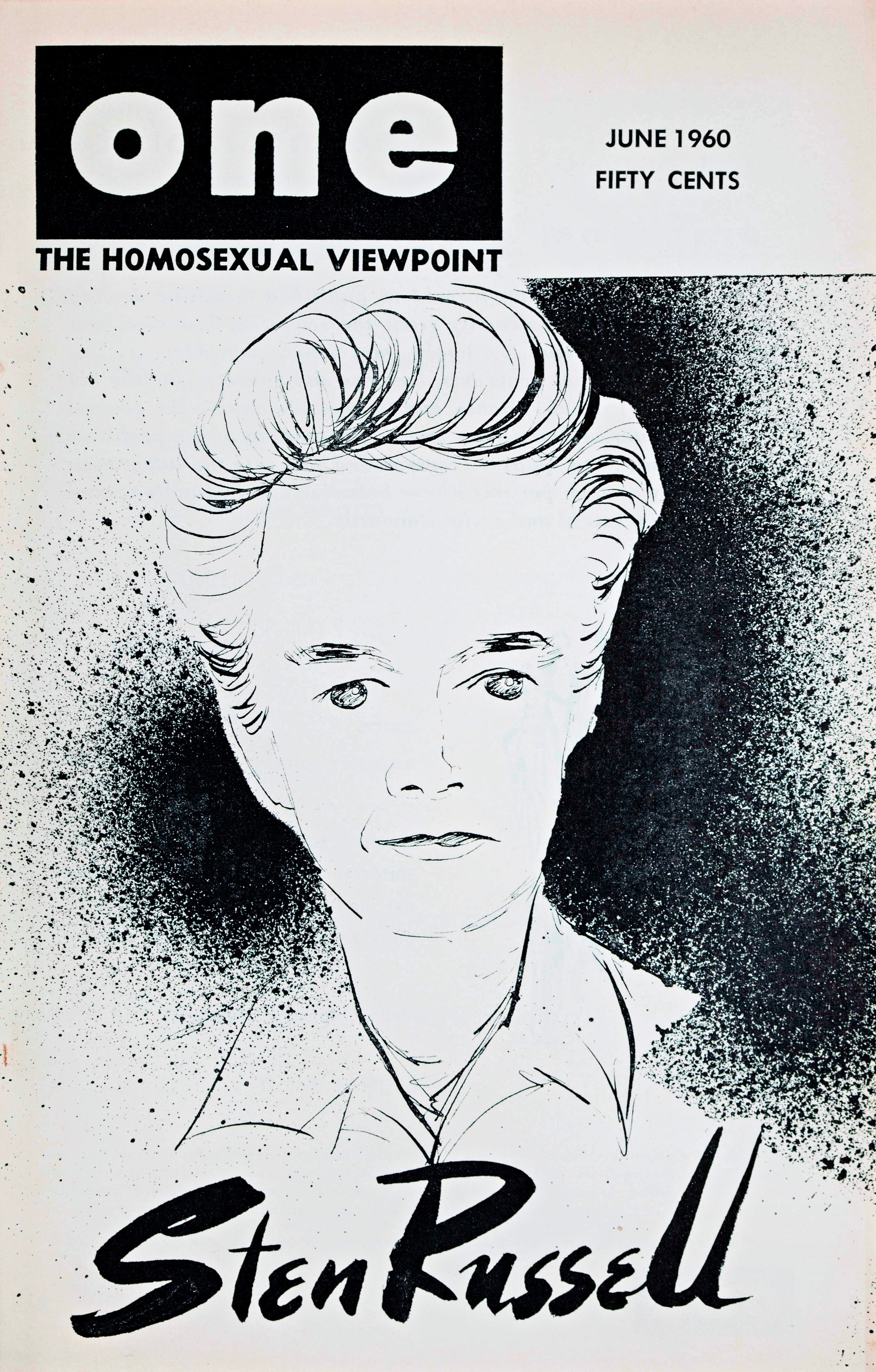

As I came to learn, Stella Rush was ahead of her time. She defied the binaries that defined the lives of women in the mid-20th century (gay/straight, butch/femme) and she defied society’s expectations—marriage, kids. She took a huge risk by writing for ONE magazine while working as a civil servant at the peak of the Lavender Scare. If discovered, she would almost certainly have been fired. That’s where “Sten Russell” came in, Stella’s nom de plume. Sten was the byline for dozens of ONE magazine articles beginning in 1954 and it even graced the magazine’s June 1960 cover.

In 1956 Stella began writing for The Ladder, the Daughters of Bilitis magazine, as well. But by the late 1960s her work as a reporter, writer, and poet was over and Stella retreated from any active role in the movement.

Two years before I met Stella, her partner of 30 years, Helen Sandoz, who went by “Sandy,” had died. The two met at a ONE meeting attended by members of the Daughters of Bilitis, including Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin, who became lifelong friends. (Have a listen to our MGH episode featuring Phyllis and Del.) My impression from talking with Stella was that, without Sandy’s stabilizing influence, she was struggling.

As with most of the people I interviewed for my oral history book, I didn’t stay in touch with Stella. And when we began work on Stella’s Making Gay History episode, I assumed that Stella was no longer alive. When we tried to find out what had happened to her in the intervening years, we kept hitting dead ends. Stella’s Wikipedia page showed her as still being alive. We knew historian Marcia Gallo had spoken with Stella in 2002, but her last-known address in Westminster, California, just led to three disconnected phone numbers. No obits. No death notice. Nothing. So maybe Stella was alive after all. But maybe not.

It wasn’t until we called in a favor from an investigative reporter friend to pull background check information that we turned up a record of the date Stella died: July 25, 2015. She was 90 years old.

We kept digging. More disconnected phone numbers and bounced emails, but eventually—and, sadly, after we had finished recording the episode—we heard back from someone who Stella had lived with toward the end of her life. Sue Beck characterized herself as Stella’s “chosen daughter.” Sue was able to fill me in on the later years of Stella’s life.

What I learned from Sue was that she met Stella and Sandy in 1972 at a meeting of The Prosperos, a spiritual organization based in southern California. Sue was then 24 and was quickly taken under Stella and Sandy’s wing.

Sue told me that in later years Stella stayed in touch with an “old lesbians group” in San Francisco and corresponded with many people. She also met a wide-ranging group of people through meetings for lesbians with substance abuse issues. Sue explained, “They didn’t realize Stella’s history with the movement. She was just a sweet lady who would talk to them for hours through any crisis.”

As Stella’s physical health declined, Sue said she moved Stella to an assisted living facility a mile away from where she lived in Westminster, California. But Stella feared that she wouldn’t be accepted because she identified as a lesbian and soon moved into Sue’s guest room. Stella lived with Sue for several years before moving to a nursing facility in Anaheim where she spent the final three years of her life.

I asked Sue why there were no obituaries or even a death notice about Stella and she explained that Stella said “we should let her notoriety die out.” Sue added, “She was self-effacing and very private to most people. Stella had not disclosed to many acquaintances her background in the lesbian civil rights movement and she didn’t want to shock anyone after her death. We had talked about it several times as she grew more and more frail, and she told me that she wanted to fade out of memory and didn’t want a ceremony. I told her I didn’t know if I could do that, and she told me to do my best to keep it simple. I tried to follow her wishes, and feel she also has a place in history that needs to be documented.”

Six months after Stella was cremated, Sue, who is an ordained deacon, presided over a burial at sea arranged through the Neptune Society. Sue recalled, “Stella wanted to be a part of the eternal ocean.” It was the same burial that Stella had arranged for her beloved Sandy.

To learn more about Stella Rush, I suggest exploring the resources, links, and full transcript of her Making Gay History episode that follow below.

———

Read a biographical overview of Stella Rush by Judith M. Saunders in this chapter from Before Stonewall: Activists for Gay and Lesbian Rights in Historical Context, edited by Vern L. Bullough. In the same book, Rush herself also contributed a chapter on her longtime partner and fellow activist Helen Sandoz (aka Helen Sanders) here.

Watch a May 15, 1987 interview with Stella Rush and Helen Sandoz (off-camera) from the Lesbian Herstory Archives’ Daughters of Bilitis Video Project.

In the late 1980s, Jim Kepner wrote an essay on Stella Rush, Helen Sandoz, and the other women who contributed to ONE, which you can read here. For a historical overview of ONE magazine, ONE, Inc., and the ONE Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries, go here. Be sure to check out our episode on the founders and early contributors to ONE, including Kepner, here. You can read Rush’s resignation letter from ONE, Inc. here.

You can read a snippet of Rush’s reporting on the 1960 Daughters of Bilitis convention in San Francisco in The Ladder here. For information about The Ladder, the magazine published by the Daughters of Bilitis, read Malinda Lo’s AfterEllen.com article. And take a tour of a GLBT Historical Society exhibit about The Ladder in this video.

To learn more about the Daughters of Bilitis, read Marcia M. Gallo’s Different Daughters—A History of the Daughters of Bilitis and the Rise of the Lesbian Movement and be sure to listen to our episode with DOB co-founders Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, too.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History!

In our last episode, you heard from some of the men who started ONE—the trailblazing organization that published the first national gay magazine. But ONE was made up of more than just the men. Unlike the Mattachine Society, which focused on gay men, and the Daughters of Bilitis, which was the first lesbian organization, ONE set out to include both men and women from the start.

Stella Rush was one of the women who wrote for ONE. But you wouldn’t find her name in the magazine. Instead, you’d need to look for Sten Russell. Stella and Sten were two sides of the same coin. Sten was Stella’s pen name—a byline that appeared regularly in ONE magazine beginning in the mid-1950s. Stella was a woman caught between categories, in search of acceptance. She was bisexual, and described herself as “ki-ki,” a derogatory term used in mid-century lesbian culture for women who didn’t sort themselves into the butch-femme binary.

Growing up gay in the 1970s, I often felt like I just didn’t fit in. I think we’ve all felt that at times. But for Stella Rush, that was her whole life.

The stories Stella told me offered a window into a world I never knew. California in the 1940s and ’50s, where even in the homosexual underground there were strict rules constraining roles and relationships. And Stella didn’t like rules.

So here’s the scene: I arrange to meet Stella at her Costa Mesa, California, apartment—about an hour south of L.A.—but when I get there she heads me off at the pass. She says that her place is a mess and she’s got three people staying there besides, so she ushers me into her landlord’s apartment, which contains her landlord and his gurgling fish tank. Out the window, children are at play.

Stella is dressed in a light-colored polyester pants suit, black shoes, and a cap over short, salt and pepper hair. Her fingers are chewed to the bone. As I disentangle wires and get set up, Stella pauses from chewing on her nails. I clip the microphone to her jacket and press record.

———

Eric Marcus: Interview with Stella Rush. Monday, August 21, 1989. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Tape one, side one.

Stella Rush: Um, Gary, do you need to watch your TV? We can go back upstairs, hon. Cuz this is gonna go on…

Landlord Gary: No. [Inaudible.]

SR: Okay.

Gary: I’ll just turn the light on in this place.

SR: I’d like it if you pull the doodads, cuz it’s real bright in my face…

Gary: Sure, you can go on.

SR: I had been in love with one guy in college. He was a Black man, and, I mean, it was a true love, and we were engaged to be engaged, and nobody talked to us but communists, and we weren’t communists. I was nearly thrown out of my dorm.

EM: For dating him.

SR: Yeah.

EM: Because he’s Black.

SR: Yeah.

EM: Which, where were you at school?

SR: I was at, um, Berkeley. The war had not quite ended yet, as I recall. I think they dropped the bomb on Hiroshima right after I got up there. [Makes exploding bomb sound.] Mushroom cloud. And I met Dave. So I tried, you know? Even though, well, okay, okay, I’m capable of loving both sexes.

And so I was dating this guy, and I was going to bed with him, and—oh, God, he was beautiful. I was in love with his body, as an artist. So it was a big thing to get married and have kids because you’re supposed to get married and have kids. With David, I knew that I couldn’t raise Black and white kids. You know, mixed Black and white kids. I wasn’t even sure I could raise kids that weren’t of a mixed racial marriage. So I thought that, I thought that I chose, chose the gay thing.

I came out in December of 1948, at the old If Club. And it was half gay, half straight. It was a tourist bar. So I sat up where the tourists sat. And I dressed like a gay person, but I didn’t know they had a uniform.

EM: What do you mean, you dressed like a gay person?

SR: I had on Levi’s and leather jackets, and you didn’t do that in 1948 unless there was something really strange.

EM: Why did you do it, then?

SR: I just thought I was asserting my individuality. I didn’t know that meant you were gay. I mean, I thought, that’s perfectly ridiculous. I felt more comfortable that way. I’ve always hated women’s clothes.

And these two women tried to pick me up. And they were real feminine looking. Well, they had come from their jobs and they were dressed—well, I didn’t dress that way on my job. I cannot remember, I’ve never been able to sort that out. How come I was dressed that way? Maybe I wasn’t working that day. I sure as hell couldn’t go to work like that. I’ve always conformed to whatever minimal standard of dress you had to conform to as a woman in order to work. But, ugh, pantyhose, didn’t even have those then. Garter belts. You name it. Yuck! Anyway, there I was, and they tried to pick me up, and I said no. I was hostile. Came up to my end of the bar! Silly twits.

So I go to the bathroom, and this lady whose name, I think, was Betty… Yeah, it was Betty and Valerie. And she was real sweet, and she said, “Hey, gonna ask you one more time. You look lonesome. And we just want to take you to a bar. We’re not going to hurt you.” And whatever. I don’t know. I don’t know how she put it, but she put it really nice. And I thought, Oh, what the hell. Why not? “We’re gonna go to a bar and dance.” And I told her I wasn’t gay. And she said, “Mm-hmm. Yes. Of course.” [Laughs.] “Sure.”

Well, we get to this—I can’t even remember the name of the bar. It was down in Venice on the beach. And it’s all women, and they’re dancing. Valerie, although she looked very feminine, had a very strong masculine sense about herself, and she led. Well, and I only knew how to follow in dancing. I only knew how to follow a good man, a good dancer who had a strong lead. And I had to be kind of half-smashed to do that. Well, okay. I enjoyed the dancing very much, but the whole atmosphere of the place, and the whole… I thought, well, it’s just like the books, it’s terrible, that’s what it is.

EM: Why? Can you describe what you mean?

SR: Well, because the connotation of having to live that kind of a hidden life. And in the gay bar society, you had this structure.

EM: Of butch and femme.

SR: Yeah, and of having to look that way. And what happened that night was that somewhere in the middle of the night I woke up, and I thought, Oh my God. And I went back over my life, had I ever really loved a woman that I wanted sex with?

So then when I went back to the bar, deciding that I was gay, by jing, and that’s what I was gonna be. And I didn’t know where else to start. God, there weren’t any lesbians in college who were going—these nasty people who would attack me, seduce me, or otherwise bring me out, so I had to go blunder into it. So I go blundering in. And I sit down, and I probably had on my Levi’s and leather jacket again, and I sit down in the gay end of the bar.

EM: And because you dressed that way, what did people assume about you?

SR: They assume I’m a butch.

EM: Which meant what then?

SR: Well, that was where the bad news came. I sit down, and the first question this girl asked me, and I tell her, “Wow, you know, I’ve just figured out I’m gay! And here I am, and what do you gotta know?” Well, first she says, “Are you a butch or a femme?” I said, “What’s that?” This was the first piece of bad news. The language was so ugly to me. All these bleepin’ words that you had to know, and they were all ugly. And she told me what a butch was, and a butch as close as I could figure out was an imitation man. Did all the things that men did, and it sounded really tiring. I said, “Well, okay, what’s a femme?” Well, that was worse. They didn’t say it was worse, but I mean, they defined femme for me.

EM: Which was?

SR: Well, you know, you went out on the butch’s elbow here, and you were, you dressed the way feminine women dressed, and it sounded to me like the butch imitated a man, and the femme imitated the way we think feminine women should be with their man. And I just simply said, “S’posin’ you’re both?” “Ah, my God,” she said, “don’t say that.” I said, “Don’t say what?” I said, “S’posin’ you’re both, you got a word for that? I’m both.” She said, “Don’t say that, Stella, that’s almost as bad as being bisexual.” Well, I already knew I was that, so, oh good, I can go kill myself. [Laughs.]

EM: So you were a bisexual butch femme.

SR: I’m a bisexual ki-ki sonofabitch butch femme. Oh, boy! You know, I thought, Oh, if I had any place to run, I’d go there.

EM: A bisexual what, I’m sorry, butch femme?

SR: I said ki-ki. K-I hyphen K-I. Ki-ki is the equivalent of, in the gay world, of a woman—she can’t make up her mind. One minute she’s a butch, another minute she’s a femme, you know? She can’t make up her mind. And it’s almost as bad, quote-quote, as being a bisexual between the two worlds.

EM: Uh-huh.

SR: That’s the ultimate low.

EM: Mm-hmm.

SR: I was in trouble. Definitely in trouble. Because, you know, well, you know, okay, what was it gonna mean if I was a ki-ki? Well, it was gonna mean that I was gonna be ostracized. And I was.

I was attracted to a woman more masculine than myself. But in that society, I was a dead duck. Because a, you know, a butch could not afford to make love to another obvious butch. I mean, there was something terribly wrong with this, you know?

And I may not have much masculinity. And I didn’t see myself as having a lot of masculinity. But I don’t think I would have survived without what I got. I don’t plan on any asshole butch confused person taking it away from me.

And so I just, you know, went, now hear this. I have cut myself in half to be part of this gay society, you know? I have this potential. Now, in order to belong to this group, I have to cut off my heterosexual potential. That leaves 50 percent of me. And if you think that I’m going to cut the 50 percent of me into 25 percent, you’ve got another think coming. Screw this. I am ki-ki. And I know that there’s plenty of people around here who probably are, because there’s nothing normal about this crap. It’s not normal.

I could understand denying that you were gay, because of all—or a lesbian, or whatever, before you came out, because of all of your fear, and all the consequences that would mean in your life. But once you accepted yourself enough to get into this life, why, then you had to go play all these damn games. Well, I think it’s because maybe I had a handle on the masculine/feminine part of the self.

EM: You were comfortable with who you were.

SR: Well…

EM: Or you were just so much in the middle that you could not—

SR: I just simply, I mean, I just… What I did know of myself I wasn’t willing to give up any of. What little I knew of myself was important to me.

EM: You had to lie in the outside world, and you sure as hell weren’t going to lie in the world that you were becoming a part of.

SR: Yeah. No, no way.

EM: Yeah.

SR: I just seem to be maimed all over the place. I was too busy fighting for survival, social survival, anywhere I went. You know? It didn’t seem to make any difference where the hell I was, I was fighting for social survival, to be myself.

EM: Did you begin writing for ONE then, did you go to meetings for ONE magazine? How, what was your involvement?

SR: I was, well, I was, well, I was on the periphery there, from ’53 on. And I was, I was scared to death, really, all during that period, I was simply terrified.

EM: Of what?

SR: Of getting into an organization that might make me public.

EM: Mm-hmm.

SR: One way or another.

EM: So you were frightened about even going to meetings, or associating with any of the people involved?

SR: I was just scared all the time.

EM: Let’s talk a little bit about the pseudonym issue.

SR: Oh, okay. Sten Russell to me is not a pseudonym so much as it is a pen name. It was, at the time, a way of buying time.

EM: When you say “buying time,” what do you mean?

SR: Well, at that time, I was in civil service, and at that time, boy, practically all you had to do was point at someone.

EM: And?

SR: And, well, in the ’50s, with McCarthy and the witch hunts, they were, you know, homosexuals…. And at that time, there was a moral turpitude law. Homosexuals, they were immoral by definition. And they didn’t have to prove you were sleeping with anybody, they just had—well, all they had to do was make accusations. At least that’s the way it felt at the time, because this was back, we’re talking, when I was in that particular civil service was 1950 to 1971.

EM: So when you say “buying time,” you mean…

SR: Well, because if I wrote under my own name, and somebody was out to get me, and they happened to see it in a gay magazine like the Daughters of Bilitis or ONE or the Mattachine or whatnot, and they wanted to do me in, all they’d have to do would be to spin it across my boss’s desk, say, “That’s Stella Rush.” And then he asks me, “Are you Stella Rush? Are you this…,” you know, whatnot. It just seemed easier that if I was Sten Russell and he says, “Is this you?” Why, I mean, uh, I’d figure out what I did then. In other words, I couldn’t be identified instantly from my writing. To me, it is a writer’s pseudonym, it’s a pen name.

My first name, my Sten, was an interesting thing. I wrote for a while under the name of Ben, because I was so pissed at the butch/femme thing. ’53 was when I got associated with ONE, and ’55 I was writing poetry, and the young woman who was keeping my poetry, who was Eve Elloree, who was an artist on ONE magazine, she couldn’t stand the Ben.

EM: The Ben?

SR: Ben.

EM: The first name Ben.

SR: Yeah. Ben Rush, or whatever I was signing my stuff. She took the STE from Stella, and the N from Ben, and filed me under Sten. And then when I had to come up with a name to write my stuff for, for in the magazines, I picked the name of the street that we lived on. Russell. And that fit good.

EM: Did the men at ONE magazine take women seriously?

SR: They were men. I really would say in defense of Don Slater and Dorr Leg and Jim Kepner, who was the more, the softer—that’s not to say he doesn’t have strength—but the liberal and the softer and the see-three-sides-of-everything kind of person. But all those men were serious in their attempt to make it a coeducational organization. What they didn’t know, and couldn’t know, particularly Don and Bill, was that women didn’t have any practice in that. I mean, a woman either came along and was strong enough, dumb enough, and sure enough of herself… They either were integrated and knew who they were and they had these strengths or they didn’t. There was no way to get them in a male-dominated organization, and they were, it was a male-dominated—by necessity, it was invented by them, for God’s sakes. But they did try, much more, from what I can tell, to integrate women. That’s why their feelings were very badly hurt when I went to the DOB thing.

EM: Were there real differences between the men’s and the women’s issues at ONE?

SR: Sure. I mean, that was, okay, that was part of the reason that the DOB really had to be founded. And I believed in what ONE was doing. I mean, inside my intellectual head, I was so male-oriented, I didn’t know what I was missing. But I did know I was dying. Because their issues were not my issues.

I got tired of being the swing vote! The only time I had a chance in the damn editorial vote was when one of them would waver on something that I felt very strongly about, I was voted down time after time after time.

EM: About?

SR: Take advocacy. I don’t believe in advocacy. This life ain’t no better than any other life if it’s not for you. I mean, homosexuals are better. Who needs this? Straight people are better. Who needs that? I mean, it’s the same crap going in the other direction.

We were supposed to be educational. And we were supposed to be trying to change laws. And in the DOB we were doing that, plus we were trying to integrate the lesbian into herself, with herself, accepting herself, so that she could then be integrated into society. And advocating that our way of life is better than the heterosexual way of life, we felt, was a good way to get ourselves stamped off the face of the earth.

———

EM Narration: Stella Rush did step away from ONE and its advocacy. She resigned from ONE Incorporated—the organization that published ONE magazine—on July 23, 1961. She found a happier ideological home at The Ladder, the Daughters of Bilitis magazine, which took a less militant stance. Stella’s partner, Helen Sandoz, worked in various roles at The Ladder, including editor. And Stella wrote for the magazine through the 1960s, but stepped away from activism after that.

Stella Rush and Helen Sandoz were together for 30 years until Helen’s death in 1987. Stella died almost 30 years later, on July 25, 2015. She was 90 years old. There were no public obituaries. The last place we traced Stella to was Westminster, California.

Like many early activists, the people who put everything on the line for the movement, Stella’s life and her work have gone largely unrecognized. In their later years, so many trailblazers have been forgotten to the point of erasure.

Huge thanks to everyone who makes Making Gay History possible: executive producer Sara Burningham, producer Josh Gwynn, production coordinator Inge De Taeye, social media producer Denio Lourenco, photo editor Michael Green, and our guardian angel, Jenna Weiss-Berman. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

The Making Gay History podcast is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and ONE Archives at the USC Libraries. Season four of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Calamus Foundation, and our listeners—like Hirschel McGinnis. Thanks, Hirschel!

With the holidays just about here, why not give Making Gay History to someone you love, or even someone you just like a lot. Head to makinggayhistory.com and click on the merchandise tab to find Making Gay History t-shirts, tank tops, hoodies, tote bags, mugs, and pillows, too. Or, if you’d like to support us directly, just click on the donate button on our website, where you can make a tax deductible donation of any amount.

And you can stay in touch with Making Gay History by signing up for our newsletter at makinggayhistory.com. Our website is also where you’ll find previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people we feature.

So long! Until next time!

###