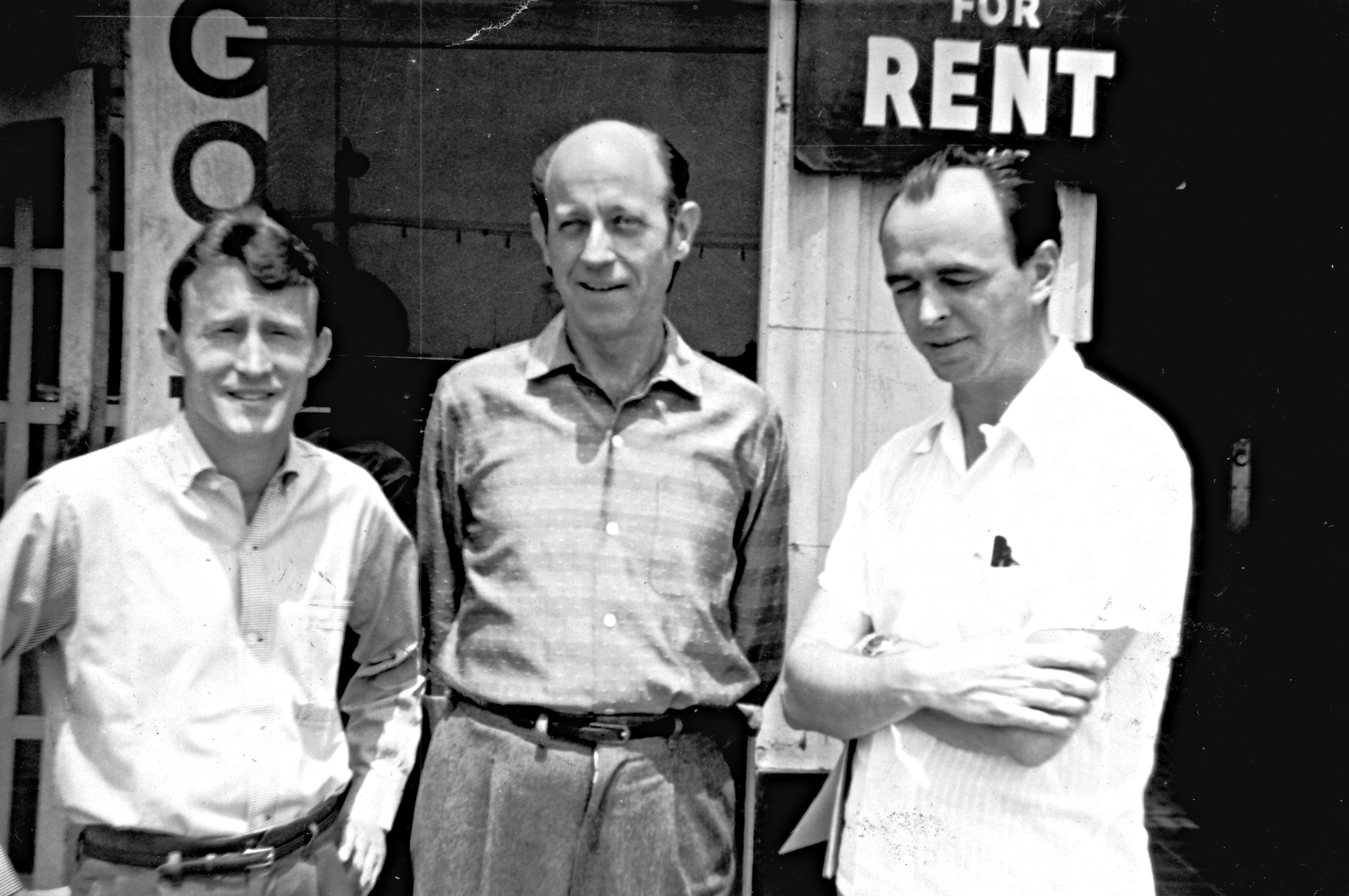

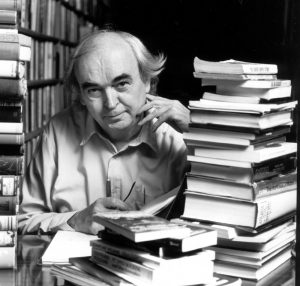

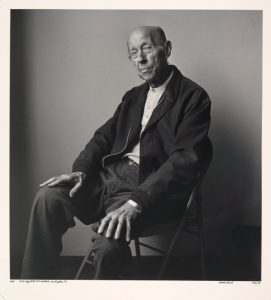

Legg, Block, and Kepner

Credit: Courtesy ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Credit: Courtesy ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.Episode Notes

From Eric Marcus: Over the course of one week in August 1989, I interviewed three of the men who played key roles in the publication of ONE magazine, the first national pro-gay magazine, which first hit the newsstands in January 1953. They couldn’t have been more different: Dorr Legg, the patrician landscape architect from Michigan; Martin Block, the self-described Jewish anarchist New Yorker; and Jim Kepner, the one-time communist who was found as an infant under an oleander bush in Galveston, Texas, wrapped in newspaper.

And while all three were passionate about their pioneering work on ONE magazine—a monthly publication that attracted the attention of the FBI and was at the heart of a landmark U.S. Supreme Court case—their equally passionate recollections of the magazine and its founding didn’t line up. Not even close.

Who to believe? This wasn’t the first time I’d interviewed people for my oral history book whose memories differed in ways big and small. And early on I decided that I’d let the people whose stories I recorded speak for themselves. So in this episode of Making Gay History you get to hear history as it happened, as it was remembered, and perhaps as Dorr, Martin, and Jim wished for it to be remembered.

Please explore the resources that follow below, which will help you decide whose memory is closest to the historical record (but please bear in mind that the historical record offers differing versions of ONE’s history).

———

For a historical overview of ONE magazine, ONE, Inc., and the ONE Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries go here. The website has other useful LGBTQ educational links as well.

To explore the ONE Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries, go here. In 2010 NPR’s Tell Me More did a short piece on the archives, which you can listen to here. It features the voices of Jim Kepner and Edythe Eyde, the subject of this season one MGH episode.

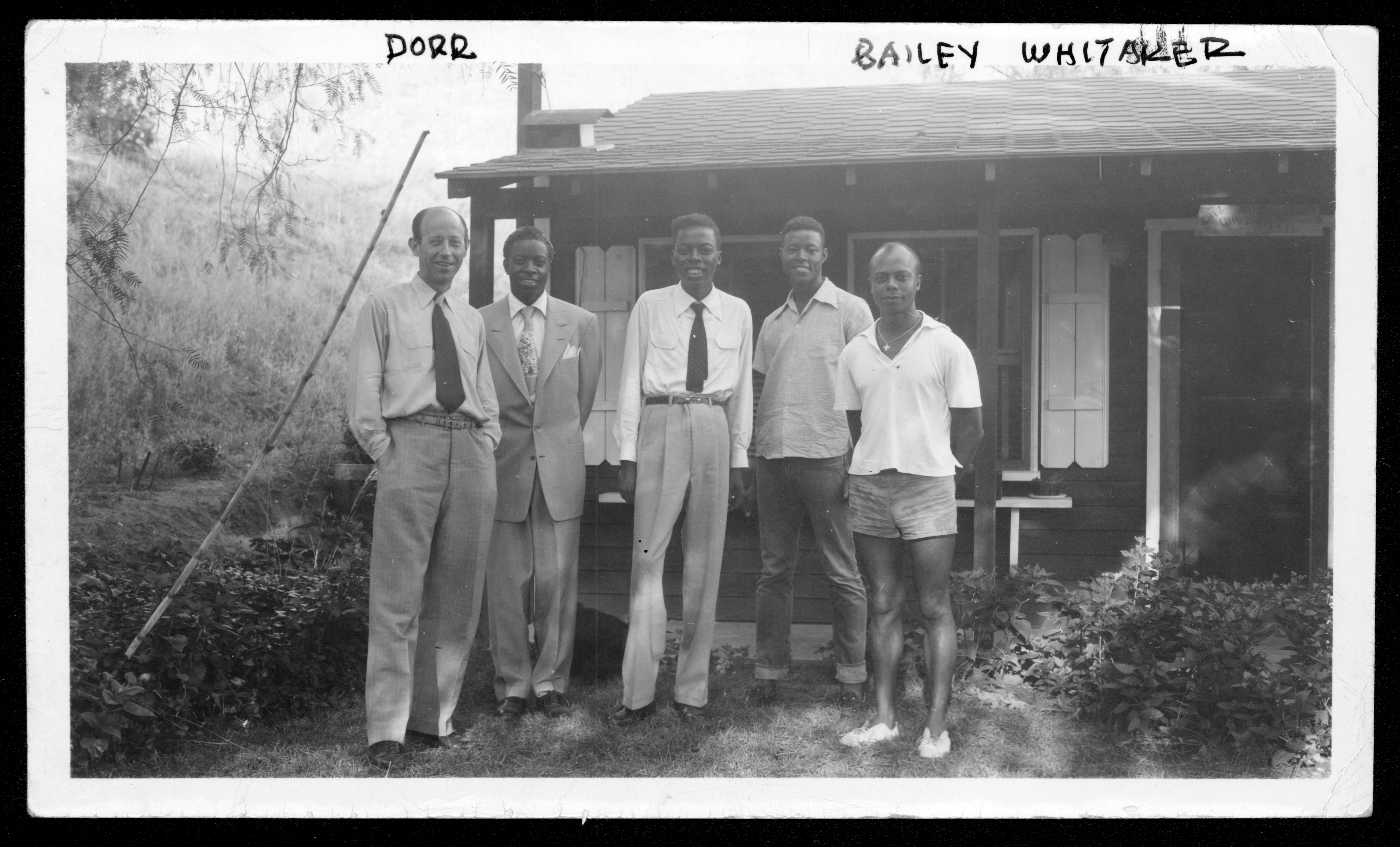

ONE got its name from a quote from the 19th century Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle. The quote reads, “A mystic bond of brotherhood makes all men one.” Dorr Legg credited Guy Rousseau, an African American school teacher whose real name was Bailey Whitaker, with finding the quote and suggesting the name.

For a biographical sketch of Dorr Legg from the GLBTQ Archives, go here. Please note that the bio misidentifies Legg’s lover at the time Legg moved to Los Angeles as “Merton Bird,” who was the founder of an early gay organization called the Knights of the Clock. According to Legg in his original MGH interview, his then lover’s name was Marvin Edwards. A 2010 article from the Gay & Lesbian Review set out to uncover the history of the little-known Knights of the Clock, of which Legg was an early member. The article also provides additional details about Legg’s life.

Check out Homophile Studies in Theory and Practice, edited by Legg, here.

While Dorr Legg, Jim Kepner, and Martin Block may not have been on the same page about ONE magazine’s origin story, they all chose to leave their personal papers to the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries. Dorr Legg’s papers can be found here. Jim Kepner’s papers can be found here. And to see what Martin Block’s papers contain and to read a brief bio of Block, go here.

Learn more about Jim Kepner in his New York Times obituary and this Tangent Group obit. LGBTQ pioneer Barbara Gittings, who was featured in MGH seasons one and two, spoke at Kepner’s memorial service in 1998; read her words here.

In 1969 Jim Kepner participated in the first mass gay protest march in Los Angeles. Watch this video of the protest in which Kepner is briefly interviewed at 11:52 by pioneering activist Pat Rocco.

In this video, shot at New York City’s 1994 Gay Pride Fair, Kepner talks to gay activist Randy Wicker, who was the subject of this MGH episode.

Some of Jim Kepner’s articles in ONE and other publications were collected in Rough News—Daring Views: 1950s’ Pioneer Gay Press Journalism, edited by John Dececco; you can find it here. For an exploration of Kepner’s work as a collector and archivist, specifically in the realm of sci-fi, watch this Monomania L.A. short.

Martin Block’s and Jim Kepner’s oral histories can be found in the original edition of Eric Marcus’s Making History. You can also read a 1994 interview with Jim Kepner conducted by Paul D. Cain here.

In this MGH episode, Kepner talks about how ONE ended up in J. Edgar Hoover’s crosshairs. To learn more about Hoover, check out J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets by Curt Gentry.

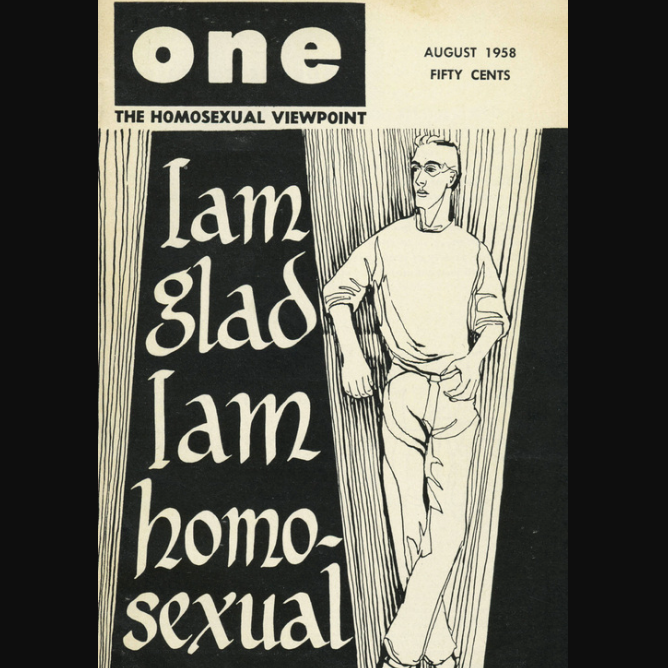

MGH’s episode with Harry Hay, co-founder of the Mattachine Society, touched on how dissemination of materials via the U.S. post office that portrayed gay people in anything other than a negative light was illegal, and how Mattachine’s mail would be intercepted as a result. In 1954, an issue of ONE magazine was declared “obscene” by the U.S. Post Office Department, which refused to deliver it. ONE, Inc. sued and, in 1958, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed a lower court ruling in One, Inc. v. Olesen, extending free speech protection to the gay press—the first gay rights victory in America’s highest court. Read more about the landmark court case in this Los Angeles Times article by David G. Savage.

To get a sense of the alarmist tone adopted by those who sought to “protect” the public from “perverted” materials, check out this 1965 short propaganda film titled Perversion for Profit. ONE magazine makes brief appearances at 9:53 and 11:05. Learn more about this hyperbolic film here.

In our episode, we asked MGH listeners whether they had any information about Merton Byrd, the enigmatic man whom Dorr Legg identifies as the founder of the Knights of the Clock. Michael J. Leclerc, who’s a professional genealogist, did some digging and was able to tell us the following:

Merton Byrd was born in Xenia, Ohio, on August 25, 1918, the youngest of eight children of Edward Walter and Ella Mae (Brown) Byrd. His father was a railroad laborer. His parents divorced by 1929, and both remarried. Merton lived with his mother, siblings, and stepfather, Thomas Stewart. His stepfather was a machine operator in a cordage factory, and his mother worked as a maid. His grandfather Benjamin Franklin Byrd was born into slavery in Kentucky; his family moved to Xenia after the Civil War.

In 1942 Merton enlisted in the U.S. Army at Tacoma, Washington, but was released a little over two weeks later. Unfortunately, most of the Army service records from that period were destroyed in a fire, so no more information about his separation from the Army is available.

By 1944 Merton was living in Los Angeles. In 1959 he was convicted of forging checks from the Pacific Coast Wrecking Company, where he was employed as a bookkeeper. In 1960 he appealed the conviction, asking for a new trial, but the appeal was denied. Interestingly, the court case included testimony about Merton suddenly getting fashionable clothes and a flashy car.

Merton died on January 12, 1976 (location unknown).

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History!

In this, our fourth season, we’ve been looking at the beginnings of the LGBTQ civil rights movement in the U.S. But the thing about beginnings is, they’re often contested. When it comes to questions of who started what when, one person’s fact is another person’s fiction. That’s especially the case with oral histories, like the interviews I recorded three decades ago.

Our ability to recall the past is surprisingly fallible and easily derailed by ego and emotion. We remember things as we think they happened and often as we’d like for them to be remembered. We choose to remember some things and not others, and our individual impressions of the same event rarely match those of other witnesses to history. But what oral histories can do, is they can take us inside how a person felt about a moment in history, and how they perceived their place in that moment. And that matters.

In this episode, we’re going to hear different viewpoints from co-founders of a key early organization in the fight for LGBTQ rights in the U.S.—ONE magazine. Or ONE Incorporated. Or just ONE, depending upon who I asked. And I asked a lot of people about ONE, and got very different answers…

———

Eric Marcus: ONE Incorporated came into existence when then?

Dorr Legg: October 15, 1952, in my home.

———

Jim Kepner: There is a problem with some of the very inventive people, that they come to the point where they feel they have to invented everything.

———

Martin Block: Dorr wasn’t even at any of the first seven or eight meetings. I don’t think he was around for the first year.

———

Jim Kepner: Dorr never quits. He seizes control of any organization he works in and keeps it at his level.

———

Martin Block: And Dorr has done so much, which cannot be denied, really so tremendously much that he doesn’t need the credit for that.

———

Dorr Legg: One hundred percent wrong, all of them.

———

EM Narration: That last voice you heard was the inimitable Dorr Legg. He’s the one who claimed ONE magazine started in his home. And you heard the magazine’s first editor Martin Block say that wasn’t so. In three interviews within the space of a week in August 1989, I heard various versions of ONE’s origin story, from three of the men who were there from the beginning. Or near the beginning.

A little later we’ll be hearing more from that first editor of ONE magazine, Martin Block, as well as one of the first writers to work on the magazine, Jim Kepner. But let’s start with Dorr Legg—or William Dorr Lambert Legg, who was born in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1904 and claimed his ancestors came to America in the 17th century. Decades before he joined the fledgling gay rights movement, Dorr earned a master’s degree in landscape architecture and taught at the University of Michigan.

By the time I meet Dorr in 1989, he’s living on a large property in a residential neighborhood just west of downtown Los Angeles. Dorr shows me around the beautiful grounds, which he tells me are cared for by his lover of two decades.

There’s a grand mansion on the property, which houses ONE Incorporated’s 4,000 square foot library. Dorr takes me through row after row of storage boxes stacked on long tables, and he shows me drawers filled with little physique magazines—sort of gay porn before there was gay porn—almost naked men in posing straps.

There’s a second, smaller house, which is where Dorr and his lover live. Both houses need a ton of work. But not Dorr. He’s trim and well-dressed in gray slacks and a pressed white shirt. I had no idea he was in his mid-eighties until he told me.

Dorr Legg’s story in the movement starts with a secret society in Los Angeles in the late 1940s. Dorr and his then lover Marvin Edwards had just moved to L.A. from Michigan, as an interracial couple in search of a more accepting place to live.

———

Dorr Legg: The first organization was of course the Knights of the Clocks. The Chicago organization of 1924 was incorporated, lasted about six weeks, but the Knights kept on for years.

EM: Were you with your lover by the time you joined Knights of the Clock?

DL: Yes, and no. I met him in the East back when I was there, and I made a very professional analysis of every city of 100,000 in the United States on a professional city planning level.

EM: You did it, did the research about a racially open city because…

DL: I wanted to find a place where we could be.

EM: Where the two of you could be.

DL: Yes. And I didn’t want to come to L.A. I’d been here, I didn’t like the place at all. I said, I used to tell people, “It’s just nothing but Detroit with palms,” and which was not a recommendation, and, but on the other hand, I every chart came out L.A. L.A. I thought, well, here goes.

EM: How were you and your lover treated when you came here to Los Angeles as a mixed racial couple?

DL: We had no problems of any kind.

EM: What year was that?

DL: 1949. There were restaurants you could go to, there were hotels that a mixed couple could stay in—not many, but some. This was the most wide open city in America in the ’40s, a rip-roaring town. There was open male-to-male dancing to live music in gay bars in the city, and I’ve done it. And that was not happening in any other city in America to our knowledge. So that what we were able to, what the movement was able to do, was to slip through the cracks and become strong enough to survive.

EM: Are you still in touch with anybody from Knights?

DL: Unfortunately, no. The founder of it, the one who got the idea…

EM: What was his name?

DL: His name was Byrd. Merton Byrd. Yes. He was the founder. And, um, …

EM: Merton is Black, isn’t he?

DL: Oh, yes. Yes. He was the person with the concept. He was a very enigmatic person in a way. Friendly, outgoing, very handsome man, and sort of a quiet authority that everybody listened to him. He said to me, “I have been thinking about an organization,” and he described it. Interracial. Both male and female couples. And that was what it was about. “Would you be interested?” I said, “Why, certainly, would I.” I thought, my Lord, this is something different.

When the Knights was founded, it was totally co-sexual. It was totally interracial. And it was actually the original gay community center, 20 years before there was one anywhere else in the country. It was simply a housing, legal aid, and all this it had to be.

EM: Was there an actual building that…?

DL: Oh, no, no, no. No, it was, it was small-scale.

EM: Was it a telephone number even?

DL: It got to be that I was the telephone number because I was one of the founders and so I did receive calls, but but there was a network of other people, both Black and white, in there… People were losing jobs and being fired and be getting in jail and all this sort of thing. The meetings were organized and formal and and substantial. And the social meetings could be very large, up to 200 people and very successful.

EM: Dances or…?

DL: Oh, yes. Oh, yes. It continued holding its meetings and having social events for five or six years that I know of. And but by this time, I was in the Mattachine out to my ears, and I no more had gotten into the Mattachine than we founded ONE, and I was working in my field profession at the time. So, you know, there weren’t that many days.

EM: ONE Incorporated came into existence when then?

DL: October 15, 1952, in my home. At a Mattachine meeting. This meeting was at my home and there was a, I had a big living room and dining room, and I had, I don’t know, 60, 70 people there.

EM: And this was, this had already been, the idea had already been discussed before at other meetings.

DL: Never. Never. The meeting was a pure Mattachine meeting and Martin Block was the chairman. So all these people came together. Well, the topic was, we were going to talk about police practices, which by this time L.A. was becoming very not an open city as it had been. Scandals and changes had occurred. And, and here was a vice cop, an ex-vice cop was the speaker. Sat there telling all the dirt.

EM: A gay vice, ex-vice cop.

DL: No, no.

EM: A vice cop who was straight.

DL: A vice cop, period, who was mad, angry, and willing to tell all. They had walkie-talkies and bugs and all this kind of thing. Guys walking on the beach with very brief shorts on, and a bug in there. Talk to me on the beach, broadcast up to the car parked up. All you had to do then was to say a word, the word would get people in jail. And so we just sat there and this man was telling all of this, and how ambulance-chasing lawyers all over town who were getting rich off of these arrests and in cahoots with the police and all of this kind of thing. And people were getting madder and madder and madder, and and people were saying, “People don’t know this and they’ve got to be told.” And…

EM: Wasn’t there a Johnny something-or-other who…?

DL: And Johnny whatever-his-last-name-was…

EM: Johnny Button.

DL: Johnny Button, who we never saw again, spoke up and said, “There should be a magazine.” Everyone started talking at once. Martin said, “I am not going to let this meeting be thrown off track. I’m the chairman and I’m going to keep it that way. Now those of you who wish to do something to talk this other thing, adjourn to another room, agree to meet at some other time, and let’s have a little law and order here.” And so we went into my kitchen in the house where I was living then, and eight or ten of us said, “Well, are we in—?” We said, yes, so all we did was set the date for the next meeting, that we’re going to meet and talk about it.

EM: Martin doesn’t remember you being at that meeting.

DL: God, it was in my house! It was in my house! See how interesting this…

EM: What’s fascinating is that the memories are so different.

———

EM Narration: Fascinating, maybe. Frustrating, totally. Much as I loved Dorr’s account of the vice cop with a conscience spilling the beans about microphones hidden in short shorts at the beach, it didn’t match up with Martin Block’s story, which he’d told me just three days before. Martin Block was the first editor of ONE magazine and a sometime anarchist who never took himself or the movement too seriously.

———

EM: Interview with Martin Block. Monday, August 21, 1989. At the home of Martin Block in Los Angeles, California. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Tape one, side one.

How did ONE magazine come about?

Martin Block: I had two friends. One named Alvin Novak, and Johnny Button. Johnny died a few years ago. And they lived together in what was little more than a shack, sort of a rear house in West Hollywood. And they were going to host one of the meetings, which were like every week, or every second week.

EM: Were there a lot of people at these meetings?

MB: Oh, at that particular meeting I think there were maybe 12 to 20 people, because they had brought and invited some other people, and we all brought others.

EM: This was to talk specifically about publication.

MB: No. This was just one of the evenings where we talked generally on general topics. And Johnny finally said, “You know, this whole thing is a lot of shit. We sit around here talking and talking. We don’t do anything. Why don’t we do something practical? Why don’t we do something real? Why don’t we start a journal or a magazine or something?” And in later years, what’s-his-name at ONE magazine…?

EM: Dorr Legg.

MB: Dorr Legg. Dorr Legg has always said about the origins of ONE magazine, saying that I of course remember the first meeting as his house. Dorr wasn’t even at any of the first seven or eight meetings. I don’t think he was around for the first year. And Dorr has done so much, which cannot be denied, so tremendously much for the what movement there is, that he doesn’t need the credit for that. It was all Johnny’s doing. It was Johnny’s push and excitement. We all got really worked up and planned the whole thing, and elected officers and I was chosen editor, which I was for a number of issues. And that was the start of ONE. And I think even the name ONE was chosen that night. The quotation from Carlysle, which I think is, “There is a brotherhood that makes all men one,” which is still used.

EM: What did you decide the purpose…?

MB: There was a spirit that brought the whole thing forth.

EM: What was that spirit?

MB: Just the sense of actually doing something. A sense of creation. And that we were doing it as a group.

———

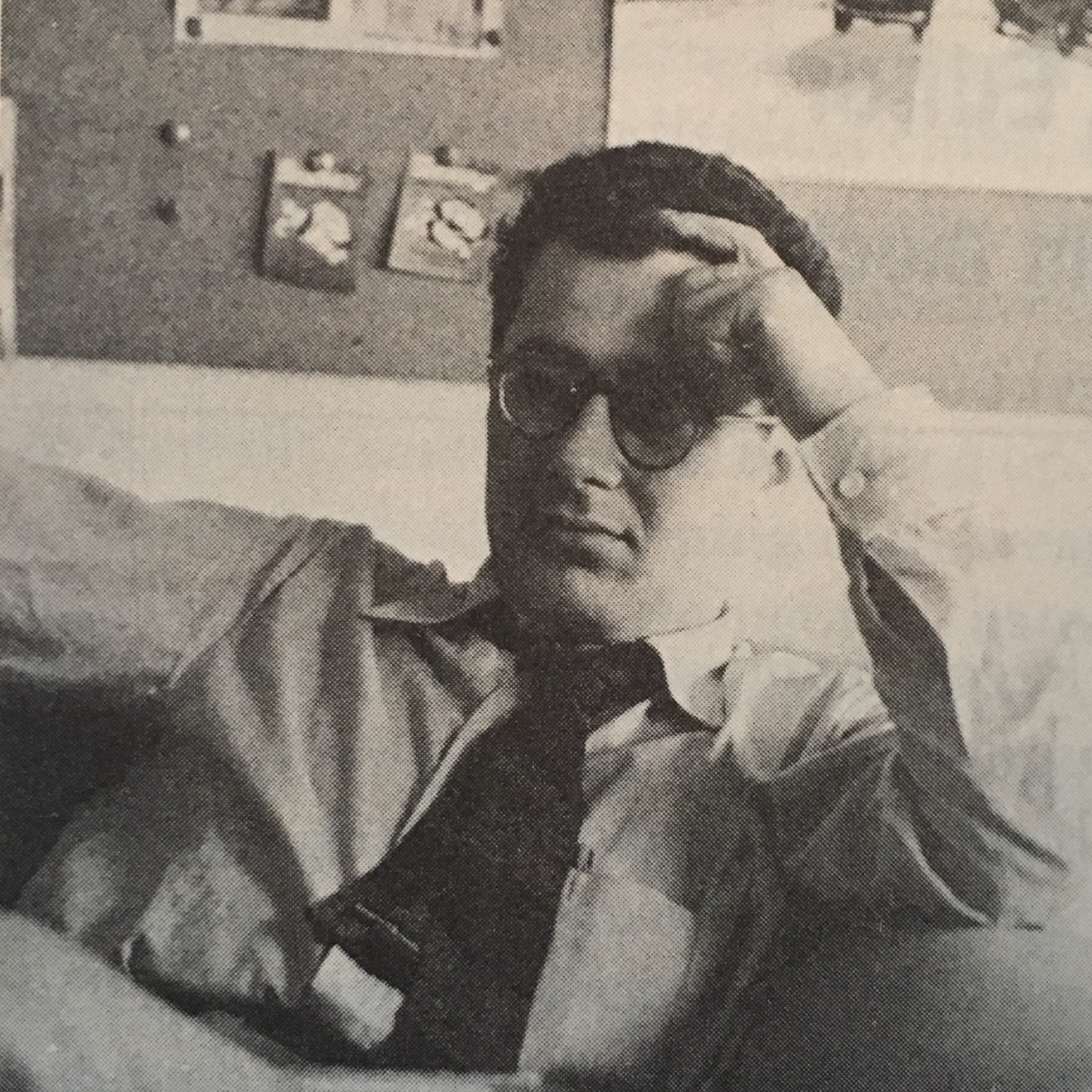

EM Narration: So Martin’s account of ONE’s founding didn’t line up with Dorr’s memories. And Johnny Button wasn’t around to ask anymore. Martin was light on detail and as the interview went on, I often found myself staring at him waiting for a response to one of my questions. That wasn’t a problem with Jim Kepner, who was so detail-oriented that I imagined his brain was as jam-packed as the heaving shelves in his tumbledown cottage, which sat at the bottom of a hilly street in L.A.’s Echo Park neighborhood.

Jim wasn’t quite as tumbledown as his surroundings, but it was clear to me that the focus for Jim was on his work, not on his personal appearance. By 1989 he had amassed a vast archive of movement-related materials, and he proudly showed me the pristine computer and printer in his home office that he was using to catalog his trove.

Unlike Dorr Legg, who came from a privileged background, the infant Jim Kepner was found wrapped in newspaper under an oleander bush in Galveston, Texas, in 1923 and adopted into an unhappy family.

At the time ONE magazine was founded, Jim was working the milk carton line at the American Can factory on the outskirts of Los Angeles. He got to Mattachine meetings whenever he could, despite the fact he didn’t have a car and worked nights.

———

EM: Interview with Jim Kepner. Saturday, August 26, 1989. Location is the home of Jim Kepner in Los Angeles, California. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Tape one, side one.

Jim Kepner: I had heard about the magazine. Dorr was running around peddling the magazine to the Mattachine discussion groups. So I began coming into the office frequently and talking to Dorr.

EM: This was by what year?

JK: Probably starting sometime in the spring or summer of ’53, ONE‘s first year. I spoke about doing some work for the magazine and discussing ideas for articles. So I began doing news reporting for ONE.

EM: What kinds of news items were there about homosexuals in the late ’50s?

JK: Well, that was a subject of much complaint from readers. The news was bad. Bars raided. Guys murdered by someone they had picked up or someone who saw them on the street and thought that they were queer. Public officials, chancellor of UC Santa Barbara or the mayor of Oswego, New York, arrested in public tea rooms. Nice wholesome news like that. And some of the readers complained like hell, and I explained several times that we did not have 500 reporters scattered around the world. We did have some readers who sent material to us, but I depended on the straight press. I was buying as many out-of-town newspapers as I could. And what I would catch was that most papers you could read for a year without finding any gay news unless you learned how to read between the lines.

EM: How do you mean that?

JK: They may not mention the raid of a homosexual or queer bar, they’d mention a house of ill repute. And if several men are arrested and no women mentioned as present, you assume it’s not a whorehouse. In the article they might mention one man was dressed in a womanish manner. You looked for those words and then read the whole thing carefully to see if this sounds like it really is in this field. Then you go investigate. Censorship questions generally. Because censorship hit us extra hard with a double standard. Anything that was heterosexual was considered obscene if it was extremely disgusting, provocative, sexually explicit, or had excessive use of Anglo-Saxon language or detailed descriptions of the mechanics. Anything that mentioned homosexuality was obscene simply if it did not point out how terribly disgusting and evil homosexuality was. No detail was permitted. That was what got the magazine hooked.

EM: Right, in the late ’50s.

JK: The August ’53 issue, which had the word “Homosexual Marriage” on the cover had been seized and released. ONE printed an angry article, saying “ONE is not grateful” to the postmaster for releasing it. Some people thought that the fact that the postmaster had released it was saying we were okay. Dale Jennings was saying very definitely, “This is nothing to be grateful for. This is bullshit.” In September, October ’54, had an article with the law of mailable material on the cover, an article by a lawyer explaining why the magazine was so tame. Readers were complaining. Just saying, “Look, we cannot have stories, even though,” he said, “other periodicals can get away with it, we can’t have stories in which two people meet in a bar, like one another, and leave together. The story has to clearly show that they went their separate ways. They may be interested, but so sorry. If two people touch, which is not advisable, it better be shoulder or above and not erotic.” “Hi there, fella.”

EM: So your stories reflected that.

JK: The stories reflected that. Every story went to the attorney and once in a while the editorial board would decide, this is a story we want, and we would argue with him. He would say, “Well, you know, this is a real risk, but give it a try.”

Even after several years working on the magazine, after two or three years working on the magazine, I was still shy about picking up that magazine on a newsstand or other obviously gay magazines.

EM: Why?

JK: Why?

EM: I’m still shy about going to newsstands now, and I don’t do it because…

JK: There was this sort of thing, you pick up five or six innocent magazines and you sandwich them. You put the embarrassing ones on the bottom. So the newsdealer starts to count them, ends up with the one you didn’t want to show on top. Then he goes to answer the phone or answer someone else’s question and you see a couple of straight friends of yours coming down the street, looking like they’re coming toward the newsstand and you sort of die.

JK: Yes, well. First, an article in ’53 had suggested that everybody knows that Jay Edgar Hoover is sleeping with Clyde Tolson, his close partner. They lived together and their mothers lived on either side of them. FBI agents had showed up in ONE’s office the next day wanting to know who wrote the article. And Dorr, Dorr can be as snootily non-communicative as anybody I’ve ever known. Dorr essentially told them to get the hell out, “I’m not gonna give you any information. What are your names and numbers? That’s all I’m interested in.”

EM: Were you there when the FBI showed up?

JK: No, I wasn’t. They visited me a couple of times, too. They visited most members of the staff. I was perhaps foolishly not as abrasive with them. They asked me if a couple members of the staff were communists, and I hooted and said that they were very conservative. I probably shouldn’t have even told them that.

EM: Had they shown up at your home or at the ONE office?

JK: Here.

EM: Here, at this house?

JK: Sat in that chair, one of them. I did say that I had been a member of the Communist Party, that I had been kicked out for being gay, that I owed no thanks to the party for that, but I would not give information about individuals who were in the party, whom I still respected.

EM: Were you frightened?

JK: I was nervous. I was nervous, yes. It was a tense situation. A couple of visits.

EM: What year was this?

JK: ’54, ’55, ’56.

EM: But it was that article in ONE magazine…

JK: That brought it on. Now, through the Freedom of Information Act we found a note from Hoover to Tolson, which I have a copy of, saying, “We’ve got to get these bastards.” And a note to the post office urging them to check into ONE.

EM: From Hoover.

JK: From Hoover. The post office seized the next issue of the magazine.

EM: Which was which issue?

JK: It was the September–October of ’54, which happened to have the article on the law of mailable material, which was a challenge to them. And up through the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, the courts found the magazine utterly obscene. No redeeming social values. And utterly destructive of all social values.

EM: What did you do during those years that you could not mail ONE magazine?

JK: For the time being, the seizure affected only the individual issue, until it was decided to be obscene or not obscene. We were forbidden to mail out any further copies of that issue. And several other issues were held up for a month or two. We began using extreme measures. Each member of the staff, several times, would take a long drive. I would drive toward San Diego. Don would drive toward Santa Barbara. Dorr would drive toward Bakersfield. Someone else might drive toward Riverside or San Bernardino. And at each town we would go off the highway ten blocks, find the mailbox, put five or six copies in with nothing but our return address on the plain brown wrapper, and mailed these all over southern California. No more than three or four in each mailbox. No more than 15 or 20 in any one town. We did this frequently until… Dorr was always too much of a skinflint. There were different enclosures in each issue, depending on whether someone was getting a renewal notice, whether someone was a high-class or low-class member, they would get a few extra pages. So a lot of issues would be right on the line as to whether they needed more postage. The post office called me in one time, about five weeks after a particular mailing had gone out, and this was one that we had delivered all over southern California. It was one of the risk stories that we had printed in that one. And we knew they were inspecting each issue for anything that they could hold it for. And they had virtually all of those issues on a couple of flats down there. And I was required to weigh each one and to put on extra postage on about one out of ten. We had mailed these all over southern California. And I thought, Oh shit.

EM: And there they were all in one place.

JK: And then the Supreme Court, in a decision that was embanked, but without opinion, without opinion.

EM: Was what, sorry? Embanked?

JK: The whole court… cleared the magazine, as the magazine is not obscene. And that sort of opened the floodgates. Because up to that time, the general assumption had been that material about heterosexuality is obscene if it is specifically vulgar, terribly crude, uses filthy language, or is intimately descriptive of specific sexual acts. Material about homosexuality is obscene if it mentions a subject without specifying strongly that it is terrible, terrible, terrible, terrible. There was a complete double standard there.

What we also discovered from the Freedom of Information Act was that there was a written opinion, which was not published. Which the FBI had looked at.

[Phone rings.]

———

EM Narration: And that’s it from Jim for now. While he answered that call about his archive, I reviewed the long list of topics that Jim had handed to me when I arrived and saw that we were only a couple of bullet points in. So I knew I’d be coming back for a second interview.

Whatever the discrepancies between Dorr, Martin, and Jim’s recollections, a couple of things are clear. ONE was a pioneering organization that went beyond the Mattachine Society’s secret meetings to take a public stand. And the Supreme Court case that Jim just talked about opened the floodgates for LGBTQ publications—a vital stepping stone towards building a national movement.

One other thing, Jim Kepner questioned Dorr Legg’s account of the Knights of the Clock—the organization Dorr claimed predated the Mattachine Society. Jim told me that the Knights of the Clock was founded after the Mattachine Society and it was a small ad-hoc group. Not the large, dynamic organization of Dorr’s memory. One person who might have been able to corroborate one way or the other is Merton Byrd, the mysterious founder Dorr spoke of. But Merton seems to have disappeared in the 1960s and I’ve never been able to find out more about him. If you have any leads, please write to me at eric@makinggayhistory.org.

Dorr Legg died in 1994. Martin Block died in 1995. Jim Kepner died in 1997. While the three men may have disagreed about the origin story of ONE magazine and ONE Incorporated, you can find their papers residing without conflict at the ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries. We owe all of them a debt of gratitude for preserving our history at a time when few others thought that it mattered.

———

Making Gay History is a team effort. Thank you to executive producer Sara Burningham and the rest of the Making Gay History crew: producer Josh Gwynn, production coordinator Inge De Taeye, social media producer Denio Lourenco, photo editor Michael Green, and our guardian angel, Jenna Weiss-Berman. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

The Making Gay History podcast is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and ONE Archives at the USC Libraries. Season four of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Calamus Foundation, and our listeners—like Eileen Smith. Thanks Eileen!

If you like your gay history in book form, HarperCollins recently republished the original edition of my book, Making Gay History, which is called Making History, in an e-book. Find it online at bn.com or wherever you buy your e-books.

And while you’re shopping, head to makinggayhistory.com and click on the merchandise tab to find Making Gay History t-shirts, tank tops, hoodies, tote bags, and mugs. They make perfect holiday gifts. And you’ll be supporting the show. Win-win.

Stay in touch with Making Gay History by signing up for our newsletter at makinggayhistory.com. That’s where you’ll also find previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people we feature.

So long! Until next time!

###