Joyce Hunter

Joyce Hunter in her office at the Hetrick-Martin Institute talking with two students from the Harvey Milk High School, 1986. Credit: © JEB (Joan E. Biren).

Joyce Hunter in her office at the Hetrick-Martin Institute talking with two students from the Harvey Milk High School, 1986. Credit: © JEB (Joan E. Biren).Episode Notes

Joyce Hunter’s childhood and adolescence were stolen from her and she was determined to keep that from happening to other LGBTQ youth. She survived suicide attempts, years in an orphanage, and a brutal anti-gay attack to change the lives of countless young people.

Episode first published April 27, 2017.

———

From Eric Marcus: Twenty-nine years after I first sat down with Joyce Hunter on December 9, 1988, to interview her in the living room of her apartment in the Sunnyside neighborhood of Queens, New York, I returned to that same apartment to choose photos with Joyce for this episode. So many of the people in the photos have since died—some of old age, but most of AIDS—that we couldn’t help but marvel that after nearly three decades, we were still here.

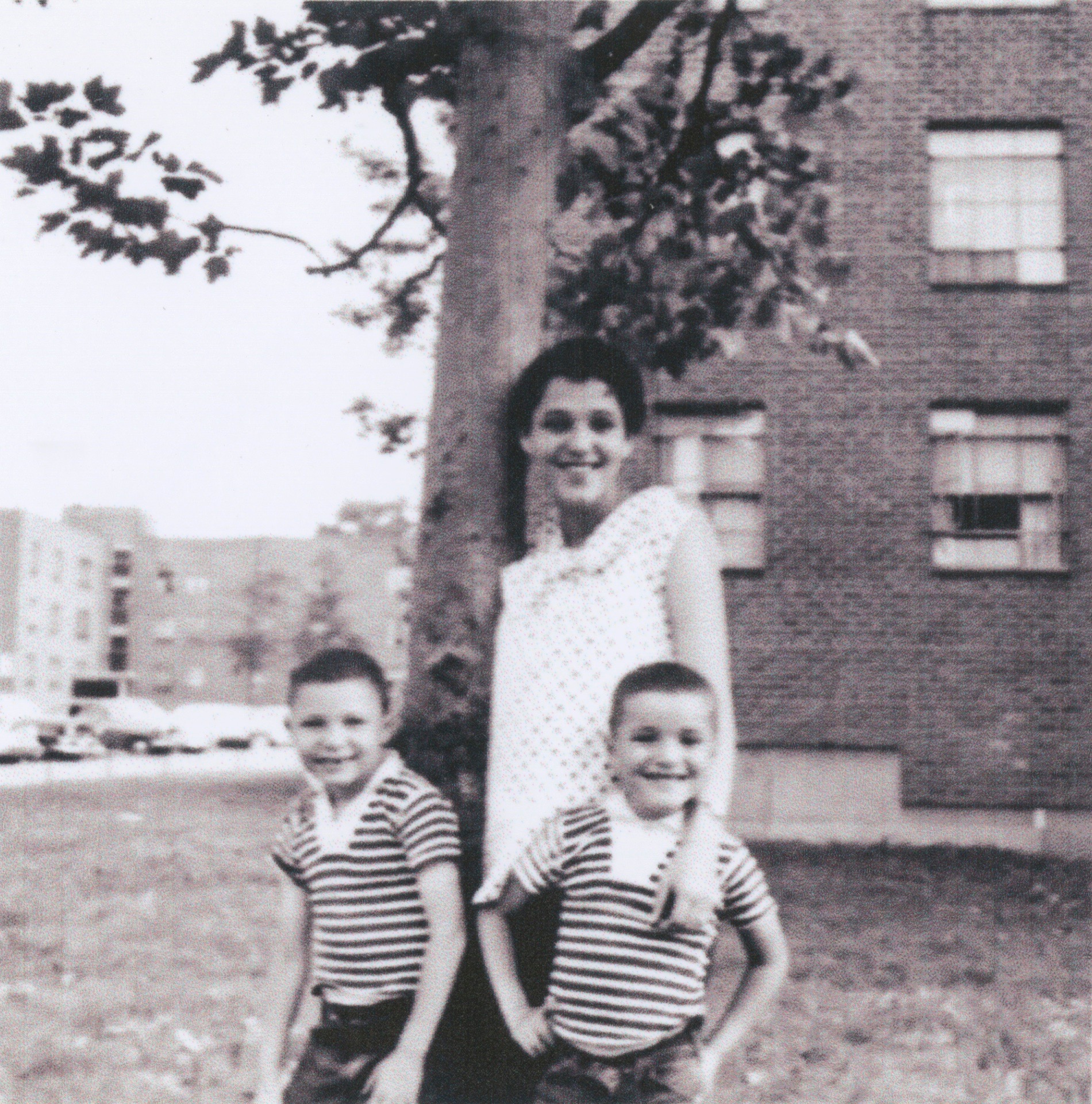

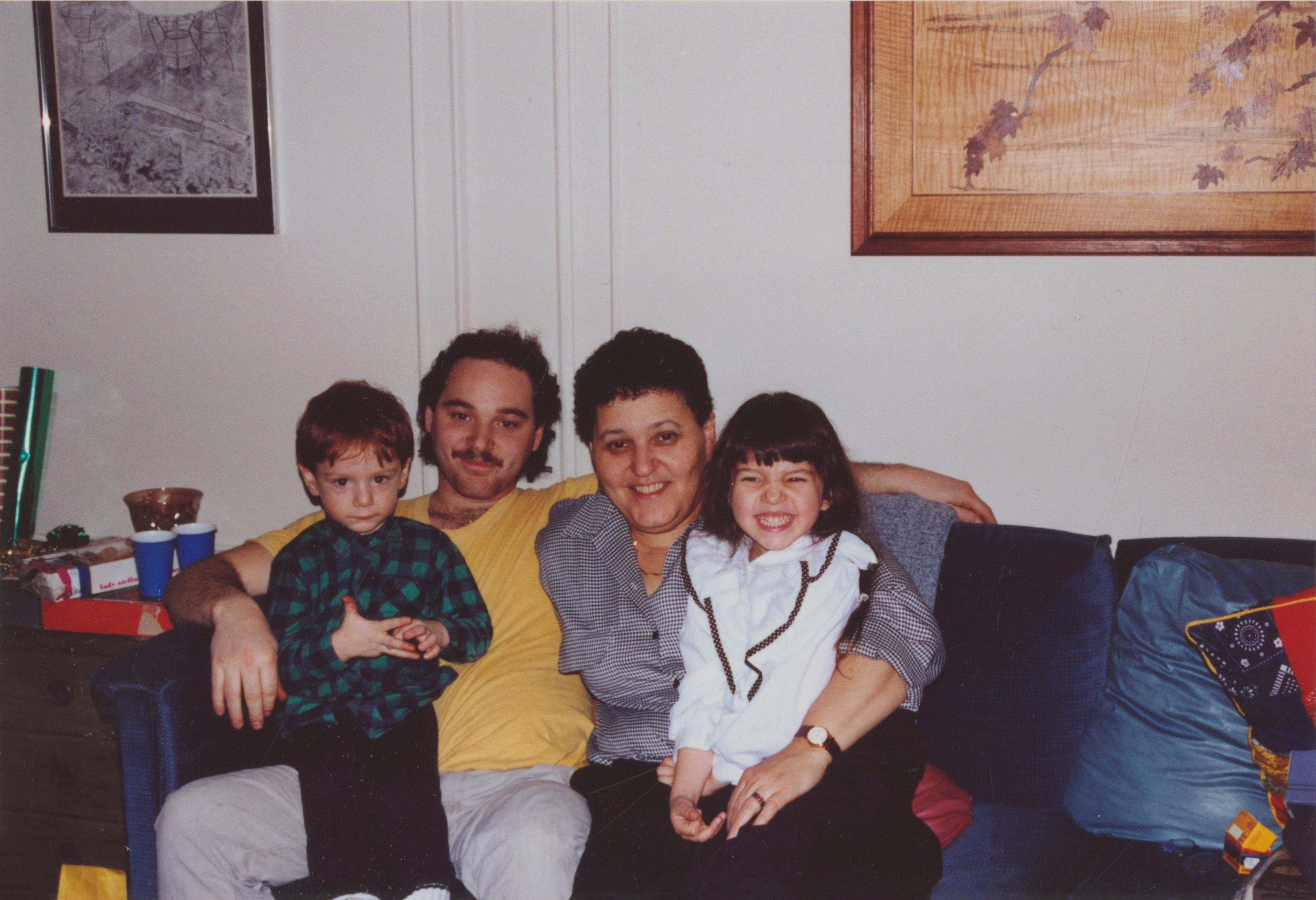

Going through scores of photos, it was also impossible not to marvel over what a survivor Joyce is and how many lives she’s lived in her 78 years—starting out as a newborn at a home for unwed mothers on Staten Island, spending much of her childhood in an orphanage, her 18th year at a psychiatric hospital, her 20s as a young married mother, her 30s as a budding LGBTQ rights activist, then college student, pioneering LGBTQ youth advocate, cofounder of the Harvey Milk High School, Ph.D. research scientist, college professor, grandmother, and great-grandmother.

I’m moved to tears when I think of Joyce’s courage and perseverance—and how, against all odds, she survived the kind of childhood she’s worked so hard in her adult life to make certain wasn’t the fate of other young LGBTQ people. Dr. Joyce Hunter is my hero.

Just a quick side note about one of the people Joyce mentions in this episode. In her original Making Gay History interview, Joyce said about Hunter College Human Sexuality Professor Mary Lefkarites: “People like Mary need to be appreciated because it took a lot of guts in 1972 for a professor who wasn’t tenured to come down to the gay table in the cafeteria looking for students to speak to her class.”

When Joyce first mentioned Mary it took my breath away because Mary is the mother of Peter Lefkarites, my best childhood friend; our mothers met in Forest Park in Kew Gardens, Queens, when Peter and I were still in strollers. I had lunch at Mary’s kitchen table with Peter every weekday for all of sixth grade in 1969. It was a complete surprise to learn that just three years later Mary played a pivotal role in Joyce’s life and that she’d been a pioneer in helping to dispel myths about gay people. I grew up with a straight ally and didn’t know it until Joyce told me. Peter died two years ago. Mary and I remain close to this day.

———

Eric Marcus’s interview with Joyce Hunter is included in the first edition of his Making Gay History book (titled Making History). Hunter’s papers are housed at New York City’s LGBT Community Center. The archive includes extensive materials related to her work in the LGBTQ civil rights movement dating from 1973 through 1998.

The Harvey Milk High School, a New York City alternative public high school primarily for at-risk LGBTQ young people, was cofounded by Joyce Hunter and Steve Ashkinazy. The New York Times wrote about the opening of “the homosexual high school” in this 1985 article.

In the episode, Hunter mentions her participation in an organization at Hunter College called Lesbians Rising. Here‘s a photo of a 1978 Lesbians Rising parade banner, courtesy of the Lesbian Herstory Archives. Hunter also discusses attending a dance for women at the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) Firehouse, which was located in an abandoned firehouse in New York City’s SoHo neighborhood. Learn more about the Firehouse here. For additional information on GAA, read this OutHistory page and this piece by John Lauritsen, who was a GAA delegate-at-large. Lauritsen’s post includes links to related pamphlets, photos, and GAA’s constitution.

Hunter also mentions her friend Harold Pickett, who joined her in addressing Mary Lefkarites’s human sexuality class at Hunter College in 1972. For more information about Pickett, who was a poet, journalist, publisher, and activist, visit this page on the website of the New York Public Library, which houses his papers. Pickett’s New York Times obituary can be found here.

Finally, Hunter also references SAGE (Services and Advocacy for LGBTQ+ Elders), which was cofounded by Emery Hetrick in 1978. In 2012, SAGE opened the nation’s first full-time LGBTQ senior center in New York City and helped found and currently leads the National Resource Center on LGBTQ+ Aging.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

Joyce Hunter had every reason to fail. In a moment she’s going tell you why the odds were stacked against her, how her involvement with the gay rights movement in the early 1970s saved her life, and how an anti-gay attack set her on a path to help LGBTQ young people. But I don’t want to get in the way of Joyce telling you herself how her life unfolded, so I’ll let her fill in the rest.

It’s a short trip from my Upper West Side apartment in Manhattan to Joyce Hunter’s Sunnyside neighborhood in Queens, New York. After a quick ride on the elevated 7 train I find myself walking down a tree-lined street with stout six-story brick apartment buildings, a lot like the Queens apartment house where I grew up. Joyce’s English Tudor-style building was built in the late 1930s, around the same time she was born.

Joyce lives on the second floor, so I take the stairs. I ring the bell and she greets me at the door with a smile. Joyce is just shy of 50, with close-cropped curly, dark hair and wears large wire-rimmed glasses. She’s dressed in slacks and a button-down shirt. Her voice reminds me of home because she speaks with the same New York accent as my mother and father. She leads me into her bright living room. We take our seats and I attach the microphone to her collar. I press record.

———

Eric Marcus: Interview with Joyce Hunter of the Hetrick-Martin Institute on December 9, Friday, 1988. Location, Sunnyside, Queens. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Tape one, side one.

Joyce Hunter: I was born in Staten Island. 1939. I was born in a home for unwed mothers. My mother and father were not married. My mother was an Orthodox Jew. My father was Black. And my mother, by the way, was 16.

EM: Sixteen.

JH: Yeah, 16, 17. She was kind of young. And my mother got ill with hepatitis and then we were taken away when my mother was in the hospital. Today they call them group homes. In those days they called them orphanages even though your parents weren’t dead. From the time that I was five until I was 14 I was in an orphanage.

EM: Did you have any sense during those years that you were somehow different?

JH: Different. Different. Definitely different, especially when I was around 10. I knew, but, you know, you don’t know what it is. And it was like, number one, they used to take us to the movies every Saturday and I was crazy only about the women. It was the only thing that I would focus on. You know what it is? You recognize difference before you recognize sameness. And I didn’t feel the same as everybody else.

EM: So at 14 you left the orphanage?

JH: Yeah. I went to live with my mother and father in the Bronx in the projects. Growing up in the Bronx and on the streets of the Bronx is… You hear everything. And then you can get your first word of “faggot” and “queer.” It scared the hell out of me. I thought that somebody was gonna come after me, but I don’t think that anybody knew. Although, I don’t look much different. You know, I was kind of like, quote-unquote, “butch-y looking,” but I don’t think they made the connection because I was very quiet and I tend not to… at that time, speak a lot, believe it or not. Then I went through a period where I wouldn’t talk at all and went into therapy because of it. I tried to commit suicide at 17. I was in a situation that was pretty violent.

EM: At home.

JH: My father was pretty abusive, yeah. And, uh, so that was a factor. Not being able to… I missed the kids from the home. You know, they were like my… I was there eight years, you know. And I didn’t like being where I was. So the homosexuality was a factor. The family situation was a factor. And I just thought it would be easier to be dead than to live.

My mother was, like, banging on the door and I stopped and she took me to the hospital. And I never went back home since. That was the last time I was in that home.

EM: When you were 17 years old.

JH: Yeah, I spent my 18th birthday in a state hospital.

EM: So you saw psychiatrists there then.

JH: Once.

EM: Once.

JH: Once. You served time there.

EM: Really?

JH: I swear to god, that’s how it was to me. I was away for almost a year, I guess. When I came out, I started seeing a therapist and I didn’t want to be gay and I didn’t everybody to hate me. And I wanted it to go away. And some therapist said, “Well, if you get married, it’ll go away.” Well, I wanted to believe it and so I did. And at 18 I went and got married to a really nice guy.

EM: Did it go away?

JH: No. I was married one year and then I met this woman, my first adult lover, while I was married, and I knew it was never going away. And I fell in love with a woman and I kept it a secret. I mean, I was so… I had never experienced any kind of feeling like that ever. You know, not with no guy. But it took me 13 years to leave the marriage. And I had two children while I was married.

EM: You must have felt trapped.

JH: Terribly trapped. When I decided to come out it was either killing myself or coming out, but I had the kids and the kids kept me from doing such a thing. And, um, so I came out and I was a much better parent for it. I have a wonderful relationship with my kids today.

EM: Did you go to any of the early gay pride marches?

JH: I didn’t go to the first one. I was not there.

EM: That was ’70—’70 was the first one.

JH: And I didn’t go in ’71. ’72.

EM: Tell me a little about that first march.

JH: I was kind of excited, almost arrogant. “Gay rights now!” You know, and excuse me, fuck you if you don’t like it. It was like… One of the things that the movement did for me, it gave me a vehicle to express my anger.

EM: What were you angry about?

JH: Everything. That I had been denied my life. That I had no adolescence. My childhood was robbed. I always say that when I come back in the next life I want to come out at two and I want to be able to enjoy being who I am.

Let me just tell you how I got involved in the first place because I think that might help a little. My former lover took me down to the Fire House. And this was 1971. I remember walking in and it was a woman’s dance. And I was, like, really overwhelmed. I’ll never forget that moment and it was exciting. And to see so many gay people on the street because people were coming out on the street. Never, never saw anything like that.

When I was growing up I didn’t think there were any gay people at all. And I just thought I was this odd entity, you know. And it was like, you know, oh, wow. All I could say was, “Oh, wow.” It was just like… ooh.

EM: You found home.

JH: For me, it was like coming home. This is it. This is who I am.

EM: What were you doing for a living then?

JH: In ’71 I was working in a factory. I didn’t get a high school diploma until ’75. So I was also… I had dropped out of school.

Also, going on at the same time, was my ex-lover was a student at Hunter College. They wanted to start a lesbian feminist organization and I got involved with Lesbians Rising.

Nobody wanted to be the spokesperson for an on-campus lesbian group. You know, they were concerned about their careers. And I said, “Well, I’m not a student.” And they said, “Well, we just want you to be the spokesperson.” This also meant that I was going out to other groups, representing Lesbians Rising.

EM: Did you also work with non-gay people? Did you talk to non-gay groups?

JH: It’s very interesting because in those early years most of my work was in the non-gay community, educating people. I walked into a classroom in 1972 in Mary Lefkarites’s human sexuality class. Yeah, Harold Pickett and I walked into that class. And basically we went in there and talked about who we were. Even though it was uncomfortable at first, you know, I felt that it was so important to dispel the myths about us. Because I also felt, you go into a class of 30 there’s got to be a couple of gay people in that class.

And during this time, I might add, from ’73 to ’75, all those years up, I was working with college… doing peer… gay peer counseling. But what happens was that some of these students were bringing in high school students, or kids that they had picked up on the street. And I would never say no to the kids. If they came in and they wanted counseling we would counsel them.

EM: You were at that time a peer… You weren’t a professional then.

JH: I was not a professional. I was not even a student.

EM: Were you working at the time doing something else?

JH: I was working on Pippin’s on Fifth Avenue as an apprentice chef. I was going to be a chef. Things changed for me, it was ’75 when I got attacked. And it really changed my life around. I couldn’t do the work anymore. Being a chef was out of the question. Because I was attacked and I was hurt pretty bad and it left me with a chronic back problem.

EM: You were attacked in the restaurant or you were attacked out on the street?

JH: I was attacked out on the street near NYU [New York University] on the northeast side of the park, Washington Square.

EM: For any particular reason?

JH: For being gay. It was an anti-gay attack. They came behind us and started kicking this can at me. They were kicking it pretty hard and it was hitting me and I turned around to like… I remember saying, like, “Aw, c’mon,” or something like, “What’s the matter here?” you know, “What’s this all about?” And the guy hit me. And with the first punch, my nose was broke. And the other person hit me in the stomach, which I couldn’t stand up after I got hit in the stomach and I fell down. And I was already now a bloody mess, but I got kicked in the back.

EM: And they were yelling things.

JH: “Who do you think you are? You wanna look like a man? We’ll show you.” You know, that kind of stuff.

EM: Ugh, god.

JH: The woman with me, she had to fight off the other two. And there was this guy who hailed a cab and got us in there so we got to the hospital. I was in the hospital for a month. So now I come out of the hospital, my doctor is saying, “You can’t do this work,” because I was in so much pain. My doctor told me to go to OVR, Office of Vocational Rehabilitation. They said, “We’ll retrain you.” So they took all these tests and everything and they said, “We’ll send you to college. You’re college material.” And I said, “Well, I don’t even have a high school diploma.” So they said, “Well, we’ll send you to NYU to college prep course and you’ll take the test.” And that’s what I did.

EM: What an irony! Do you ever think about the irony of that experience?

JH: Yes. Yes. I do think about it a lot. Because, what they really did, I mean, my education, I mean, then, boy, and it was… I was hungry for it.

EM: What did those… The people who beat you up had a motive.

JH: Yeah, I think they wanted to bust my face, which they half did.

EM: But their motive was not…

JH: Not to make me this better activist, no. Or this person who would go on to make some real change. No, I’m sure that was not in their… I think they wanted to put me six feet under. They sent an activist really on her way. That’s what they did. That’s what they did. They don’t know.

EM: How did you meet Emery Hetrick and Damien Martin?

JH: I came to speak at NYPAC.

EM: NYPAC was?

JH: New York Political Action Committee? NYPAC. And they were members of NYPAC.

I wanted something to happen in a big way for lesbian and gay youth and when I met them… You know how you get this feeling that the right people met at the right time? I immediately took to them. Emery was such a wonderful, warm kind of person. And he was such a caring person. He, uh, you know, he started SAGE. He was a man with vision. And he really felt that, you know, we have to start protecting our youth.

So those first three years we were basically doing education and advocacy. And we were training professionals to work with lesbian and… We were raising the issue. We got very little support from the gay community.

EM: Why do you think that’s so?

JH: Because I believe that the gay community has internalized that child molesting myth. You know? It really is. And I think that we have to get that monkey off our backs. These young people are part of our community. And we can’t deny that.

In 1983 we opened our doors for social services, direct services.

EM: Can you tell me about the first kid at all?

JH: 001, yes. And she’s doing very well today. She’s a kid who’s grown a lot. She’s going to college and working today. There’s been some real good stories. A lot of these kids come back later. It’s exciting. That’s the good part.

EM: Tell me why it’s exciting?

JH: Because they grow up with a better sense of themselves. They don’t have to work it out in adulthood where a lot of us had to work out our identity issues, our relating to other people. And that’s an important thing—to learning how to socialize. I think about when we were growing up that we didn’t have the place to develop our interpersonal skills. We were not telling our friends who we were. You couldn’t honestly discuss relationships, sex, sexuality, because we weren’t saying who we were. And it was so great to see kids having friends that were gay.

EM: This must have made you think about your own childhood when you saw these kids.

JH: It did. I remember one time Steve came to me. He says to me, “Do you know the kids are real quiet.” I said, “Well, why don’t you go back there and check it out and see what’s going on.” So he went back out there, he says to me, “I want you to go back there and you have to see this to believe it.”

So I go back there. I never thought that I would live to see something like this. A group of gay kids playing spin the bottle. And I was… I almost cried, I mean, because I was so moved by it, you know, and remembering how hard it was for me. And I just, you know, my god… I said to them, “I want you to know what I think is going on here is so beautiful.”

EM: Why was it so beautiful?

JH: Because I could have never imagined it. They weren’t lonely. They were laughing. They were having a good time. And it wasn’t like… It was very affectionate stuff. It wasn’t, you know, hot heavy sex or anything like that. It was affectionate. There was a real closeness and friendship. And it was fun. They were having fun. I didn’t have fun when I was a kid. And the realization that they’re just like any other group of kids and if you leave them alone they’re curious.

And I explained that to them. I said, “I want you to know that while I’m going to ask you to stop this because you’re in an agency and it’s really not the appropriate place, I want you to know there’s nothing wrong with what you’re doing.” And they all smiled and they said, “Aw, alright.” You know, but, I mean, it was never… nowhere in my wildest imagination that a group of kids could get together, you know, to do that.

EM: Did you feel that you’d accomplished your goal?

JH: Oh, at that moment?

EM: That this was validating.

JH: This was very validating that, you know… And it was good, clean fun.

———

EM Narration: Two years after the Hetrick-Martin Institute for the Protection of Lesbian and Gay Youth opened its doors to provide direct social services, Joyce Hunter cofounded the Harvey Milk High School. It’s a small alternative New York City public high school primarily for at-risk LGBTQ youth.

What started out as a two-room school with a dozen students at the back of the Hetrick-Martin Institute offices is now its own building adjacent to HMI’s headquarters in New York City’s East Village. Each school day, up to a hundred students fill its hallways and classrooms. HMI manages the facility and provides supportive services including mental health counseling, arts and cultural programs, job readiness, health and wellness education, and academic enrichment services—both during and after school. It’s exactly the kind of place where a teenaged Joyce Hunter would have thrived.

When Joyce said in her interview that she was hungry for education, she was not kidding. After graduating from college, she went on to get her master’s degree and Ph.D. Now in her late 70s, Joyce is a research scientist at the HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies at the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University, where she’s also an assistant professor in psychiatry and public health.

Joyce lives with her partner, Jan Baer, of 36 years in the same Sunnyside apartment where I first interviewed her 29 years ago. Between them, they have 16 grandchildren, one great-grandchild, and another great-grandchild on the way.

To learn more about Joyce Hunter and the work of HMI, go to makinggayhistory.com. You’ll find information, photos, and links to additional resources. That’s also where you can listen to all our previous episodes and sign up for our newsletter.

Before I go, I’d like to say hello to one of our listeners. Sam is a high school senior who’s got a tough situation at home. Her strictly religious parents threw her older sister out of their house when they found she was gay. Sam listens to a Making Gay History episode every morning before she goes to school and to another episode when she gets home. She tells us that the voices and the stories she hears are a shelter for her. Sam, we hear you. Hang in there. You are not alone.

———

It takes a team to bring the Making Gay History voices to life. A big thank-you to the MGH crew who make this podcast happen each week: our hard-working executive producer Sara Burningham; mentor, friend, and co-producer Jenna Weiss-Berman; special producer Bari Finkel; audio engineer Casey Holford; researcher Zachary Seltzer; our website designer Jonathan Dozier-Ezell; and social media strategist Will Coley. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division.

Season two of this podcast is made possible with support from the Ford Foundation, which is on the front lines of social change worldwide.

And if you like what you’ve heard, please subscribe to Making Gay History on iTunes, Spotify, Stitcher, NPR One or wherever you get your podcasts.

So long. Until next time.

###