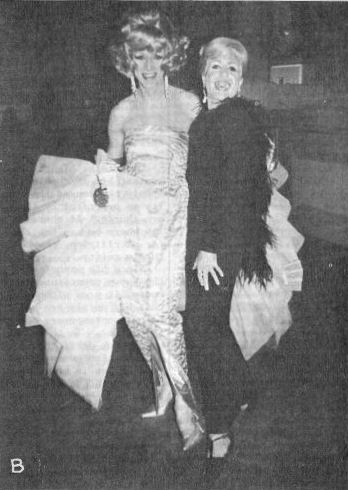

Evander Smith & Herb Donaldson

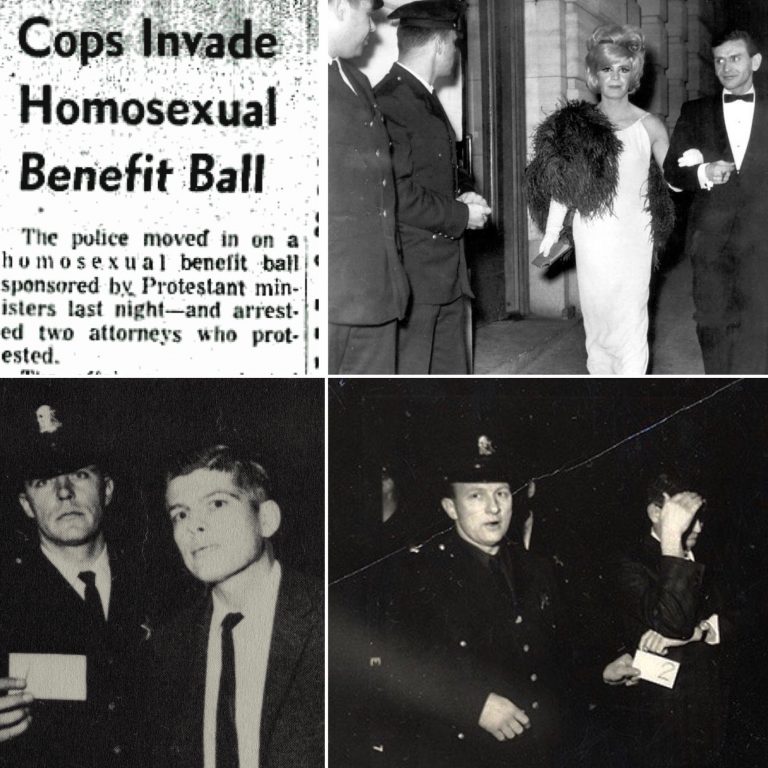

Episode Photo Collage

Clockwise from upper right: Partygoers on their way to the Council on Religion and the Homosexual Mardi Gras Ball at San Francisco’s California Hall under the watchful eyes of the San Francisco police, January 1, 1965. Credit: San Francisco Examiner.

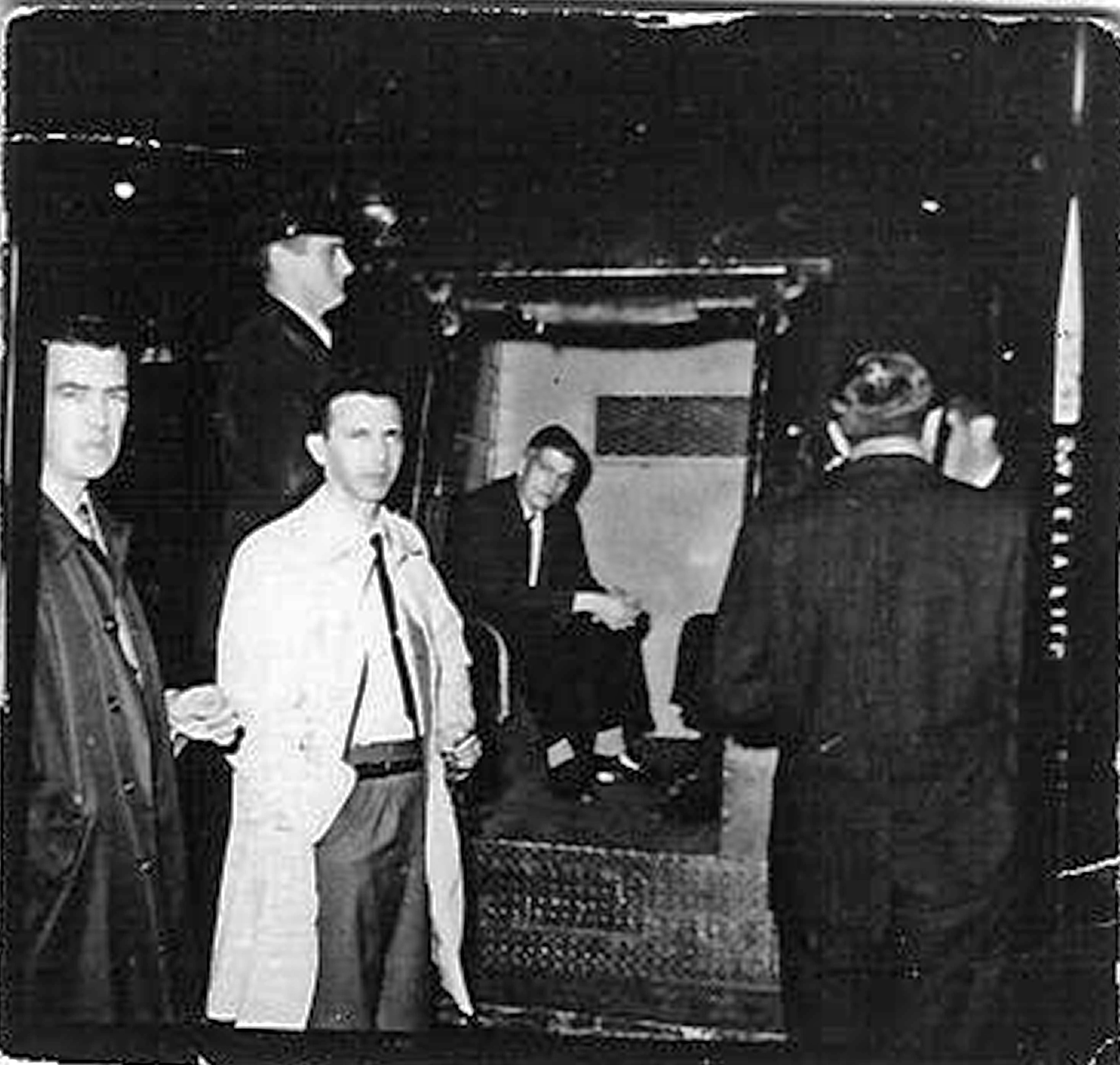

Evander Smith photographed by the police outside California Hall (the police photographed everyone entering the building using sequentially numbered cards), January 1, 1965. Credit: Evander Smith—California Hall Papers (GLC 46), LGBTQI Center, San Francisco Public Library.

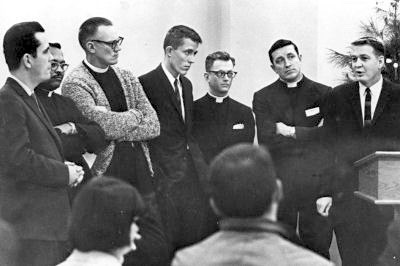

Herb Donaldson photographed by the police outside California Hall, January 1, 1965. Credit: Courtesy Herbert Donaldson.

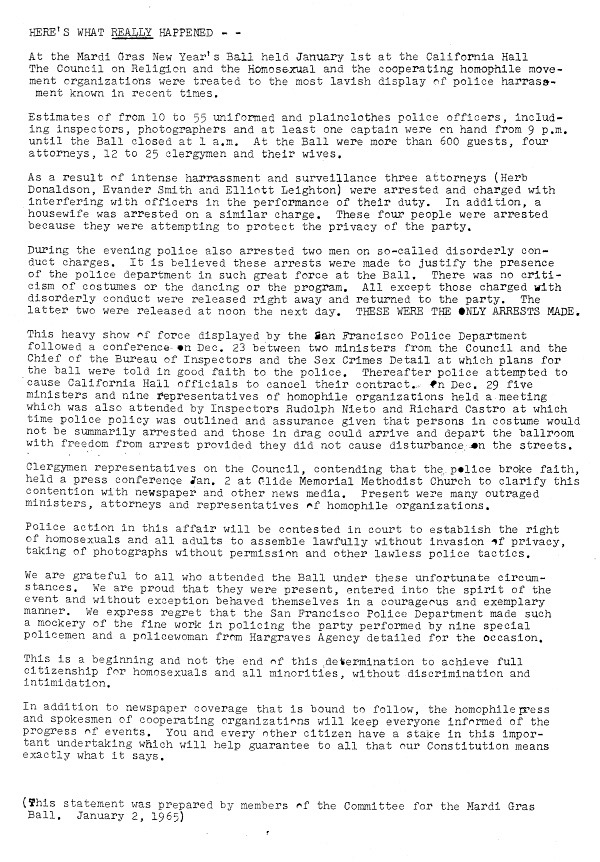

San Francisco newspaper clip, January 2, 1965.

Episode Notes

The 1969 Stonewall uprising in New York City has become such an iconic symbol of the LGBTQ civil rights movement that earlier turning points in the movement, including confrontations with the police, are often overlooked.

One of these turning points, as attorneys Herb Donaldson and Evander Smith explain in this episode, is the 1965 New Year’s Day Mardi Gras Ball in San Francisco, which was a fundraising costume ball for the newly formed Council on Religion and the Homosexual (CRH).

CRH brought together progressive ministers and local gay rights groups with the goal of educating the city’s religious communities about discrimination and anti-gay violence. Herb Donaldson and Evander Smith were among CRH’s founders and played a central role in planning the event. They met with the San Francisco police department to secure an agreement that police would allow the costume ball to take place even though cross-dressing had in the past only been permitted on Halloween. When the police reneged on their agreement, it was Herb and Evander who stood up to the police and wound up in jail.

To learn more about the Council on Religion and the Homosexual and the 1965 CRH Mardi Gras Ball, have a look at the information and links to resources that follow below, including an advertising flyer for the ball, a statement issued by the ball’s planning committee the day after the event, as well as archival photos that we’ve embedded in the transcript.

———

The LGBT Religious Archives Network mounted an exhibit on the Council on Religion and the Homosexual that includes information and great photos from the January 1, 1965 Mardi Gras Ball. Learn more about Rev. Robert Cromey, one of CRH’s co-organizers, here.

Jallen Rix produced a documentary about the CRH Ball called Lewd and Lascivious. You can read about the film and see a trailer here.

The James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center of the San Francisco Public Library holds Evander’s case files related to the trial that followed the CRH Ball. You can read a description of the materials here and a brief overview of Evander’s involvement here.

In 2006, the ACLU honored Herb Donaldson. Read a Fog City Journal article about the event.

The San Francisco Chronicle, which published Herb Donaldson and Evander Smith’s names the morning after they were arrested at California Hall, published Herb’s obituary when he died in December 2008.

Herb and Evander’s oral history can be found in Eric Marcus’s book Making Gay History.

Herb Donaldson and his partner, James Hardcastle, opened one of the first specialty coffee roasters, Capricorn Coffees, in San Francisco in 1963. You can read about Capricorn Coffees here and here. The coffee company celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2013 with a special blend in honor of the company’s founders.

For further reading on the subject of policing in San Francisco, we recommend The Streets of San Francisco: Policing and the Creation of a Cosmopolitan Liberal Politics, 1950-1972 by Christopher Lowen Agee.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

When I think of Herb Donaldson and Evander Smith I think of delicious homemade pie. That’s because I interviewed the two longtime friends in Evander’s San Francisco kitchen over generous slices of pecan pie.

I first read about Herb and Evander when I was researching the January 1, 1965 costume ball at San Francisco’s California Hall. It’s sometimes called the West Coast Stonewall because it wound up being a huge and very public confrontation with that city’s police department.

The ball was a fundraising event for a new organization called the Council on Religion and the Homosexual, or CRH. It brought together progressive ministers and local gay rights groups with the goal of educating the city’s religious communities about discrimination and anti-gay violence. Herb Donaldson and Evander Smith were among the CRH founders.

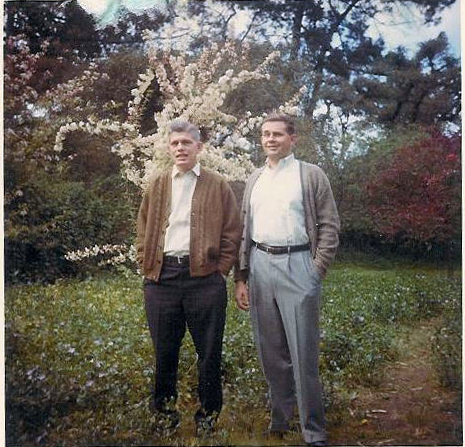

Herb and Evander met on a San Francisco beach in 1962 and the two young attorneys became fast friends. Herb had a private practice. Evander had a corporate job, but secretly helped Herb with gay cases on the side. Coincidentally, both had life partners named Jim. You’ll hear me refer to Herb’s “lover” in the interview, which is what we called life partners back in the late 1980s.

Some quick background on the two men. Herb Donaldson was born in West Virginia in 1927. When Herb was a year-and-a-half old, his father was killed in a mining accident and his mother moved him and his two brothers to Wisconsin to be near family. He served eight years in the Navy and then earned his law degree at Stanford.

Evander was born in Georgia in 1922 and raised in Alabama. His father was a minister of Scottish descent and his mother was Native American. After law school he went to Anchorage, Alaska and eventually settled in San Francisco.

So here’s the scene. It’s a perfect San Francisco evening and the sun has just set when I pull into the driveway of Evander’s huge house. It’s a beautifully kept, beige stucco two-story Colonial in the city’s gorgeous Forest Hill neighborhood. I’m 15 minutes late so I dash up the steps of the long front walk. I hate being late. Evander greets me at the door with the kind of warmth I think of as Southern hospitality and he brushes aside my apologies. He hadn’t even noticed, he says, although I’m not so sure I believe him.

Evander leads me through the house to the expansive kitchen where Herb is waiting. Herb has a full head of white hair and striking blue eyes. We take our seats around a three-sided island and while I set up my equipment, Evander asks if I’d like to have some pie. I don’t object. And once the pie is served and we’re two or three bites in, I clip the mics to Herb and Evander’s dress shirts. And I press record.

———

Eric Marcus: Interview with Evander Smith and Herb Donaldson. Thursday, September 21, 1989. Location is the home of Evander Smith in San Francisco, California. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Tape one, side one.

Evander Smith: Evander, E-V-A-N-D-E-R Smith.

Herbert Donaldson: Herbert, H-E-R-B-E-R-T Donaldson. D-O-N-A-L-D-S-O-N.

EM: And how did you come to be involved with this infamous CRH dance.

HD: There was a group of us who formed the CRH.

ES: Right. Clay Caldwell…

HD and ES: Chuck Lewis…

ES: McVan..

HD and ES: Ted McIlvenna…

HD: Louie Durham

ES: Yes.

HD: Cecil Williams. Don’t forget Cecil.

ES: Oh, absolutely. Bob Cromey. That nucleus…

HD: Bob Burr, he was one of the Methodist preachers.

ES: And Chuck Lewis, did we name him?

HD: And then the other gay organizations, and actually there were half a dozen of them—a lot of them were just simply on paper though. And they decided they were going to have a fundraiser for the CRH, in other words to get it started. And they were going to have… So it was going to be a Mardi Gras on New Year’s night.

EM: So it would be January 1.

HD: Yeah, the night of January 1.

Because everyone had wanted to do it just right, Evander and I were involved in meeting with the police to make sure that there wouldn’t be any police interference. Because at that time the police took the position that the only time you could dress up in drag was on Halloween. And this was going to be a gala affair in which if you wanted to go in drag, you could.

EM: And it wasn’t Halloween.

HD: It wasn’t Halloween. And then the police went back on their word.

ES: But they told us in advance that they had changed their minds.

EM: You said you had gotten a phone call from Hal Call?

ES: We went down to see Hal and Don and they were all shook up. They said that the cops had been there and gave them an ultimatum that they were to get this message out to these queer ministers, as they referred to them—ministers who loved queers. If they weren’t queer themselves, they were queer lovers. They were going to get rid of all these people by arresting them.

EM: The police had blocked off the intersections all around California Hall.

ES: Right, they were…had their bikes…motorcycles and also had the Black Marias or station…paddy wagons, whatever they call them. And they had their helmets, their riot gear. They would not have been any better prepared if they had gone there with the gangsters with machine guns to fight them. And they had stated previously that they were going to make mass arrests. And it did, as Herbert pointed out, come out at our trial, that they had 200 placards printed printed up, numbers, ready for that many arrests.

EM: When they told you they were planning this, what did you do?

ES: All we could do is to then see if they were going to go through with their threats.

EM: So what actually happened then that night?

HD: We were the attorneys there at the door. And we were there to make sure that everything was on the up and up so there couldn’t be any reason to make any arrests. And then they started coming in making inspections. They were the plain clothes police. They would come in. I remember there was a fire inspection.

ES: That’s right. There were several.

HD: There was a health inspection. And I think it was about the fourth inspection we just said…

ES: Where we said that that’s enough inspections.

HD: We said, “No. And if you want to come in…

ES: … and either give us your ticket or the search warrant.”

HD: And it really was completely unplanned. They didn’t know what to do and we didn’t know what to do.

EM: Were you standing facing each other?

HD: Yes.

ES: We were frightened.

HD: We were just standing there and they were standing there, because, you know, they didn’t know what to do either.

ES: They didn’t. They didn’t believe that we would stand them off. The hallway in that building is about as wide as this kitchen is wide, okay? And Herbert and I were standing abreast with each other and literally leaning to each other because I think we were both so nervous that we would have fallen down if we hadn’t had someone to lean on.

To my right you could run a motorcycle through. And to Herbert’s left you would have been able to run a motorcycle through.

HD: And they could have gone right past us. But they were afraid of us, too. Then all of a sudden there was a whole bunch of police in uniform came in. I thought that, you know, when police arrested you they said, “You’re under arrest.”

ES: Nobody told us that.

HD: And they grabbed me, one on each side. And I said, “Am I under arrest?” And what a silly question, “Am I under arrest?” And they had already hauled you off to the paddy wagon. And then they put us in jail.

ES: They sure as to hell did.

HD: But for a while they didn’t…

ES: They still didn’t know what to do.

HD: They didn’t know quite what to do because we could get out us get out, we could use the telephone to call. Anyway, but, so then… Did we or did Malcolm call Glickfeld for us?

ES: No, we actually called him from the jail. You called him from the jail.

EM: Judge Glickfeld.

HD: Yeah.

ES: Judge Bernard Glickfeld. Insane, but a doll in many ways.

HD: Because he ordered us released on our own recognizance.

ES: Then and there. But we had to go over and be booked first.

HD: We had to go over and be booked.

ES: After we got out Herbert said to me, “That booking officer that takes your photographs and fingerprints and so forth paid you a real compliment.” And I thought well, gee, did he want maybe to have a date with me or what? And I said, “Well, what kind of compliment did he pay me?” And he says, “Well, he told me that you were the nicest American Indian he’d ever met.” And they don’t get many American Indians in here that are nice.

HD: Because he’d given his nationality as American Indian.

ES: And I always put that down.

EM: He said you were the nicest American Indian he’d ever met.

ES: Because some of the Indians that he sees in the booking process, you know the poor guys are drunk and it’s a bad scene, you know.

HD: Then we went back over… somebody took us back over there. And the place was in chaos.

EM: So this was later in the evening.

HD: Yeah, later in the evening and…

ES: It was a wake. It was like a wake.

EM: What was going on? What do you mean by it was in shambles?

HD: I mean the police were walking in and out across the dance floor like they had taken over the place.

ES: They had. They had taken it over. They had completely queered the deal.

HD: And then some of the people were just terrified, especially the school teachers. I remember a couple of women who were school teachers. And they had to be… they wanted to be sneaked out the back way so they… because they were taking pictures of everybody as they left.

ES: Oh, yeah, they continued… They didn’t make any more arrests…

HD: Everybody who was coming and who was leaving…

ES: They didn’t make any more arrests but they did continue to…

HD: But didn’t they arrest those two guys who were standing on chairs to look at something, remember?

ES: Yeah, I’d forgotten all about that. I don’t remember what happened to them.

HD: Well, we represented them and they were convicted.

EM: What were they convicted for?

HD: Lewd conduct.

EM: Two guys at the dance?

HD: Yes, uh, huh, because the police, they had to show that all of this police…

ES: … had been legitimate.

HD: Yeah, so they charged these guys with fondling each other. They hadn’t been fondling each other. And Evander represented one and I represented the other. When the jury came in, Judge Lazarus said, he said, you know, “I never expected that.” He didn’t think they were going to be convicted. And then he said, “They’ve suffered enough. I’ll fine them $25.”

ES: But you see the tragic life there? Because those poor guys…

HD: … they didn’t do anything!

ES: They have to put down that I was arrested at a lewd dance performing a lewd act with another man.

HD: At that time 647a was registerable. Remember, under…?

ES: Yes, indeed, there are many people…

EM: So they couldn’t be hired by the Federal government. You could not get a job.

HD and ES: Oh, no. No, no.

ES: Absolutely not. And if they had had a credential…

HD: … it would have been taken away. They’d have proceeded to take it away.

Sometimes Evander and I will talk and the kids coming up now, they can’t, I tell you, they can’t enjoy their freedom as we have, because they take it for granted, that it was always like this, that they could walk arm in arm and kiss on the street and so forth. And, I mean, I’ve represented several couples who were arrested for having a hand on the other’s knee in a bar. I mean, something as innocent as that.

EM: Were you frightened at any point when you were arrested? This was not something you did routinely.

HD: No, what happens is that circumstances just carry you along. I’ll tell you, when we went home, Jim and I, we went to bed. And I was so touched because he said, “Oh, I’m so proud of you.” Because I was really feeling kind of low. Because I thought, I mean, there goes my legal career.

EM: This is Jim, your lover.

HD: Yeah, right. Poor Evander was fired from his job.

ES: I got up early the next morning. Went down to get the Chronicle.

HD: And of course they had our names and addresses.

ES: And there it was on the front page. And I was just sick, and I thought, oh shit. So the papers in all references have always put a demeaning attitude toward people who are gay. This now was reflected in this biased article that they wrote about the dance, you see. And when I went to work after having been arrested, boy, just my own secretary, nobody would have anything to do with me. I knew something was wrong.

So finally I was given a formal letter on Wednesday and asked not to come back until Friday. So I then thought, well, there is nothing short of a total earthquake to sink the city that will keep me from being fired come noon Friday. Therefore, you know, I think I’ll go out with my self-respect. So I call Cecil Williams up and I said, “Now I don’t expect you to do anything or say anything. And I don’t want to think I’m using you in a bad sense, but Cecil I’m using you for the same purpose that people use a condom rubber for. I’m just going to use you for show.”

And he said, “Do you want me to pick you up or you want to pick me up?” We got down there and they were shocked, to say the least…

EM: They were shocked by what?

ES: The fact that I had brought someone with me. But when they saw that I had this Black man with me, and I asked him also to wear his Roman garb, so he had his Roman collar on. They tried to excuse the reverend. They said, “Reverend this is a personal matter, would you please excuse us.” I said, “If he does, I leave too.” You know, I can be very effective on my feet. So, I took the show away from them.

EM: The air must have been thick in the room.

ES: Everybody was frightened. In a courtroom I’m not frightened. But I was frightened then because…

HD: Well, there goes your security…

ES: I was just going to say my economic security was at stake. It was the greatest thing they ever did for me. I don’t look back. I was never sad about it. I went home and faced up to reality with Jim and explained to him, “Look, for Chrissakes, I’m a member of the bar. You know, I can make a living. I didn’t have a job when I was born.”

But, Eric, we sued, Herbert and I. We sued the city and county.

HD: They knew that we had a good case. At our criminal trial we must have had 25 of the prominent criminal lawyers in town…

ES: Right…

HD: … listed on as “of council.” I mean, you had the ministers, you had the Civil Liberties Union representing us and…

ES: And those ministers now and their wives would dress up to their Sunday go-to-church clothes.

HD: … they with the collars…

ES: Yes, and they would come and sit, you see, in the audience…

HD: … at the trial…

ES: This was so important that the prospective jurors and the jury itself see the support. They realized that, look, there must be something worthwhile here. The police have got some legitimate people in here.

EM: The defendants, you mean, or the policemen?

ES: Well, the police had some legitimate people ensnarled into their trap’s what I meant to imply.

EM: Do you have any regrets about that dance, about being arrested?

ES: None whatsoever.

HD: No, it was actually one of the peak experiences. Sometimes peak experiences, you experience them afterward. But it was.

ES: Now, having agreed to that and I wholeheartedly do, and that arrest has affected me materially. I’ve never been one to lead the parade. It exacerbated my feeling of insecurity and being less worthy than I think people should be able to be. Herbert, it was like water off a duck’s back for him.

EM: Now, what was the significance of the dance in the city?

ES: It was the…

HD: Oh, was it significant… Boy, it galvanized the gay community into action.

ES: Absolutely.

HD: It… One of the things that was really humorous is that the police made this estimate there were 70,000 homosexuals in the city. No there weren’t. But when they advertise all over the… I mean, when it’s carried on the wire services there are 70,000, you’ve got 70,000 others out in the country who want to come and join that 70,000 here!

EM: That’s what the wire services carried on this dance?

HD: Oh, yes. Oh, yeah. “The San Francisco… the police estimate the population was 70,000.”

ES: Hasn’t stopped growing yet as a consequence.

HD: That’s right. We’re still coming.

EM: So there was an influx of…

HD: Of course! Yes.

ES: And this, I honestly think that it was the match that started the renaissance of awakening, if you will…

EM: So Stonewall, which happened in New York, really was quite late.

HD: It was, because this was as much a confrontation as… It didn’t have some of the violent overtones, but we stood up…

ES: … and were counted.

———

EM Narration: In addition to all the attention the New Year’s Day confrontation got in the press locally and around the country, the San Francisco police department did something that no police department had ever done before. They appointed a liaison to the gay community. That was in 1965, four years before the Stonewall uprising.

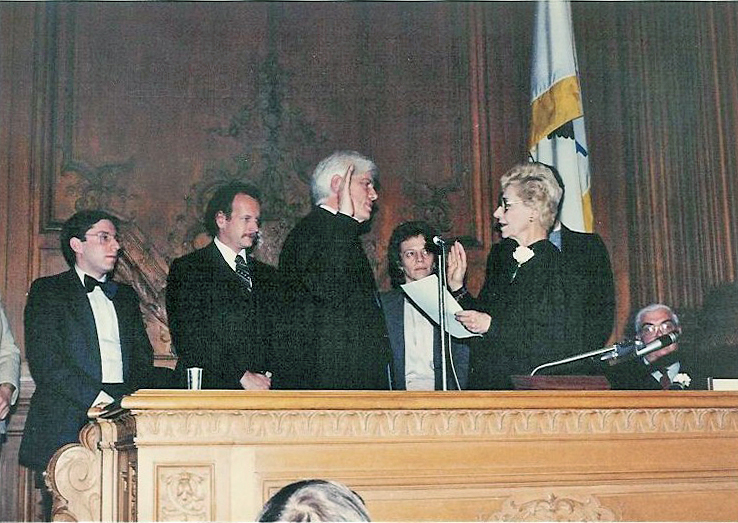

Eighteen years to the day after Herb Donaldson was arrested at California Hall, California’s Governor Jerry Brown appointed Herb as a San Francisco Municipal Court Judge. Governor Jerry Brown had offered Herb an appointment to the Superior Court, but as Herb explained to me back in 1989, he told the Governor that he would rather be on the Municipal Court because that’s where you see all the young lawyers. He said, “That’s where you can help them get their trial experience. That’s where you see the little guy get hauled into court. That’s where you get the best opportunity to do something.” Herb was the first openly gay man to serve as a Municipal Court Judge in the State of California.

Herb Donaldson died on December 5, 2008. He was 81.

Evander Smith kept a very low profile for the rest of his life. But he wasn’t forgotten. Not long before I interviewed him, he had gone for his annual physical and as Evander told me, his internist said to him, and I quote, “I was a medical student at Vanderbilt when I heard the radio report of the dance in San Francisco. You have no idea how good that made me feel. You were a part of it, and I really appreciate that.”

Evander Smith died on December 6, 2005. He was 83.

To learn more about Evander and Herb and the 1965 New Year’s Day ball at California Hall, go to makinggayhistory.com. You’ll find information, photos, and links to additional resources. That’s also where you can listen to all our previous episodes and sign up for our newsletter.

———

Before I go, I wanted to tell you about a great episode from a new podcast called Kismet. It’s a wonderful and surprising story of love taking root despite the crushing pressure of the discredited “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. You can find Kismet in all the places you can find Making Gay History.

Making Gay History is a team effort, so I’ve got a few people to thank, starting with our executive producer, Sara Burningham, and our co-producer and guardian angel Jenna Weiss-Berman. Thanks also to Casey Holford, Jonathan Dozier-Ezell, Will Coley, and Zachary Seltzer. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

A special thank-you to Herb Donaldson’s dear friend, Louise Swig, for her help with background information and photos. And a special thank-you, as well, to Tim Wilson at the San Francisco Public Library for tracking down a couple of key photographs from the 1965 California Hall ball that you’ll find at makinggayhistory.com.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division.

Season two of this podcast is made possible with support from the Ford Foundation, which is on the front lines of social change worldwide.

And if you like what you’ve heard, please subscribe to Making Gay History on iTunes, Spotify, Stitcher, NPR One, or wherever you get your podcasts.

So long. Until next time.

###