Coming of Age During the AIDS Crisis — Chapter 3

Episode Notes

A straight drug addict. A gay waiter on a ventilator. Eric is confronted with the reality of AIDS when he volunteers for the Gay Men’s Health Crisis. Decades later, he speaks with his client’s widow, for whom AIDS is a daily reality.

———

For a comprehensive overview and useful links related to HIV and AIDS, consult this HIV.gov timeline.

For a New York City-specific timeline, see this New York magazine article. (Please note, however, that the Patient Zero theory referenced at the top has since been discredited; for more information on the subject, watch the documentary Killing Patient Zero.)

This chapter covers the spring of 1984 to December 1984. According to the Centers for Disease Control, by the end of 1984 there were 7,699 reported cases of AIDS in the United States. There had been 3,665 deaths. Because there was no test for HIV at the time, the actual numbers are unknown.

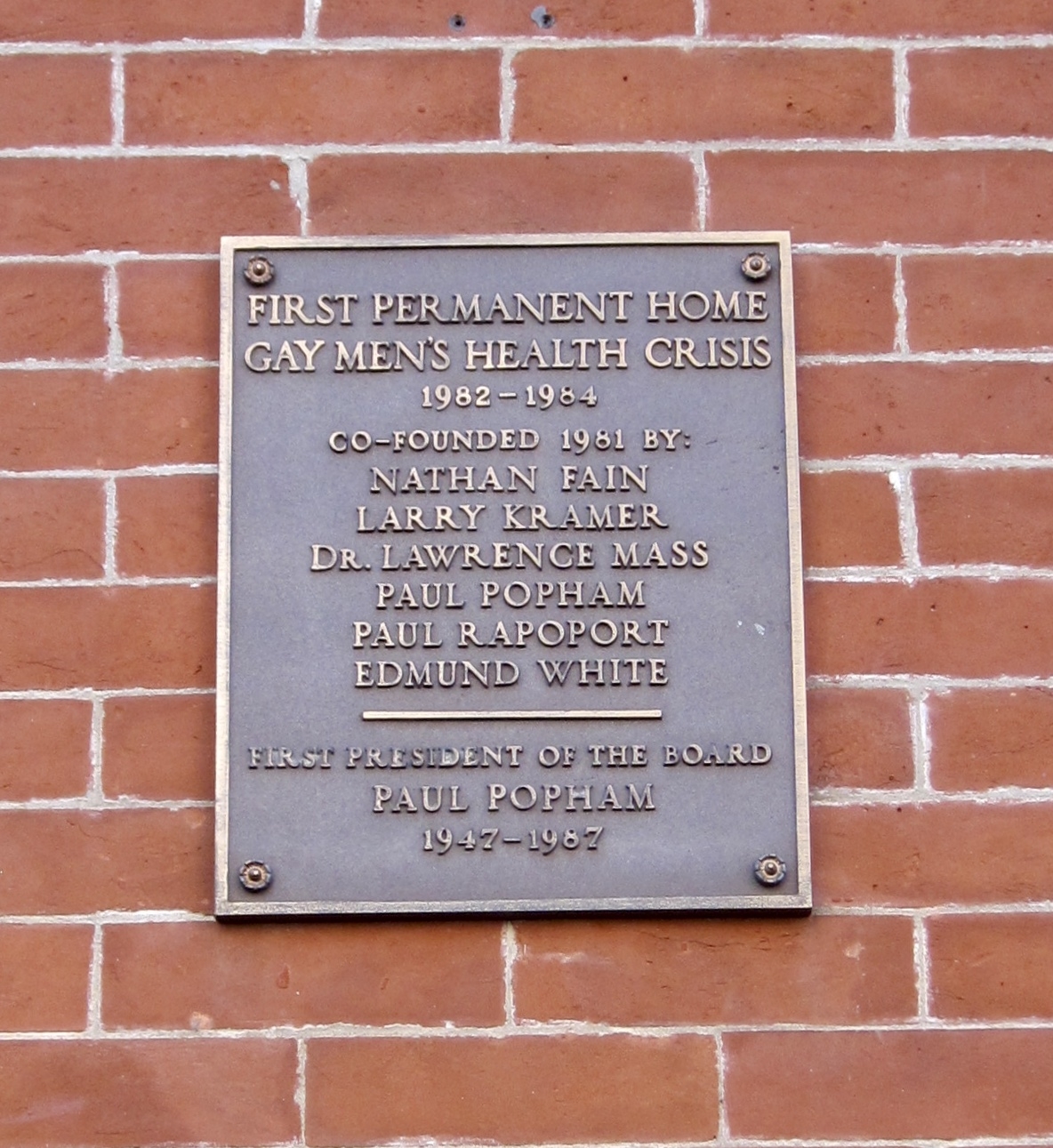

In the summer of 1981, 80 gay men met in the living room of screenwriter and author Larry Kramer to see what could be done about the new disease affecting their community; read about the gathering in this eyewitness account by Andy Humm. Six months later, Kramer and five others—Nathan Fain, Lawrence Mass, Paul Popham, Paul Rapoport, and Edmund White—founded the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC). You can read one of the organization’s early newsletters here.

Kramer dramatized this period in his largely autobiographical 1985 play The Normal Heart (later adapted into a film). Find out more about Kramer’s life and legacy in this Making Gay History episode and the accompanying episode notes. Kramer’s papers are housed at the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

The episode’s title refers to GMHC’s first headquarters at 318 West 22nd Street in New York City’s Chelsea neighborhood. The office space was donated to the organization by disco pioneer (and co-creator of the legendary gay nightclub Paradise Garage) Mel Cheren. GMHC’s archival records are kept at the New York Public Library; connecting to the Wi-Fi network at the library’s main building provides access to over a thousand videos in the collection, including organizational oral histories and volunteer testimonies.

GMHC developed a Buddy Program to help people with AIDS who felt abandoned and alone. Read one GMHC buddy’s story here. Similar buddy systems, both official and unofficial, sprang up across the country in the face of widespread prejudice and neglect. Lesbians stepped up in great numbers. Ruth Coker Burks, an Arkansas woman, dedicated herself to caring for gay men with AIDS and eventually buried more than 40 people who had died from complications of AIDS in her family cemetery in Hot Springs.

The 1985 independent drama Buddies centers on the relationship between a person with AIDS and his volunteer buddy; it was the first film about AIDS. Watch a trailer for the recently restored version here. The film’s writer-director, Arthur J. Bressan, Jr., died of AIDS-related complications two years after the release of Buddies. Geoff Edholm, one of the lead actors, died of AIDS-related complications in 1989. Learn more about the first films that dealt with AIDS here.

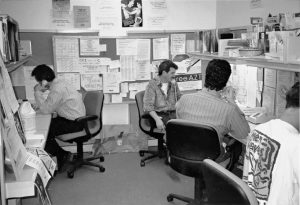

GMHC also ran a Crisis Intervention Worker (CIW) Program—the program for which Eric volunteered in 1984. CIWs provided support, companionship, and counseling; in 1984, more than 400 people living with AIDS were referred to the program (see GMHC’s annual report from that year). GMHC also helped people like Eric’s client Jimmy, who were in danger of losing their housing while fighting for their lives.

The ill treatment of those with AIDS continued even after their deaths. During the early years of the epidemic, many funeral homes were unwilling to accept those who had died from complications of AIDS, charged prohibitive “AIDS handling fees,” or refused to embalm those whose deaths were AIDS-related. Redden’s Funeral Home in Chelsea was a notable exception and is remembered by many as the only welcoming mortuary (although GMHC was able to compile a list of a few dozen citywide). Some who died of AIDS, abandoned by their families and shunned by funeral directors, were buried in the city’s potter’s field on Hart Island in the Bronx. The Hart Island Project’s AIDS Initiative is currently attempting to identify and preserve the stories of people who died of AIDS and were buried on the island; watch the project’s haunting video, Loneliness in a Beautiful Place, to learn more.

In the episode, we hear from Laura, a long-term survivor. In 1983, the CDC first reported that women were contracting AIDS from their sexual partners, but had little information to help them. In mid-1984, the San Francisco AIDS Foundation produced the first brochure in the nation to bring attention to women with AIDS, while the medical establishment and authorities continued to ignore them. The official definition of AIDS left out cervical cancer, recurrent vaginal candidiasis, and other manifestations of immunosuppression. Instead of AIDS, women were diagnosed with AIDS-Related Complex (ARC) and were denied Medicaid and other benefits.

AIDS was killing women faster than men after diagnosis. The short documentary Doctors, Liars & Women: AIDS Activists Say No to Cosmo shows how difficult it was to battle misinformation and an apathetic general public. By 1989 AIDS was the “leading cause of death among Black women 15 to 44 years old in New York State and New Jersey.” The official definition of AIDS would not be changed to be more inclusive until 1993. Learn more about the history of women and AIDS here.

Despite New York City Mayor Ed Koch’s show of support at GMHC’s 1983 circus fundraiser (see our previous episode), the lifelong bachelor, who was long rumored to be gay, is remembered for having done little to stem the epidemic. Some of Koch’s papers pertaining to AIDS can be found here.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and in this season of Making Gay History, I’m sharing part of my story—with an audio memoir and my own oral history of navigating my 20s in New York City in the 1980s, of navigating life as a young gay man in the shadow of AIDS. This memoir is also about the people I met along the way, and what happened to them.

This is chapter three: “318 West 22nd Street.”

It was a late spring afternoon in 1984—just a couple of weeks after I graduated from journalism school at Columbia University—when I walked up the steps of a Manhattan row house and into the headquarters of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis.

By 1984 more than 860 New Yorkers had died from complications of AIDS. And the administration of Mayor Ed Koch had spent just $24,500 in response.

It would take several years, thousands of deaths, and the relentless pressure of activists like members of ACT UP—the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power—for the city, the state, and the federal governments’ response to catch up to the scale and urgency of the crisis.

I wanted to help. To do something. And in New York City in the early 1980s, there was only one place to go if you wanted to do something to help in the AIDS crisis: an old brick townhouse on West 22nd Street in Chelsea.

When I came here to volunteer in 1984, it was a very different neighborhood. And I was different, too. I’m trying to put myself back in my 25-year-old self’s shoes. I’m retracing my steps. And I’m retracing the steps of hundreds of GMHC volunteers and staff, like Bill Kux.

———

Eric Marcus: So I’m here with Bill Kux in front of Colonial House Inn, which is a bed and breakfast on West 22nd Street in New York City. And it is nearly 40 years since this was the headquarters of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis. Um, there’s a plaque on the outside of the building that notes that it’s the first, it was the first permanent home of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis. And, Bill, maybe you can describe to me what we’re looking at, um, on the street.

Bill Kux: Um, well, now we’re looking at a beautiful bed and breakfast that has window boxes and flowers and, uh, beautiful ironwork. And it bears no relation to what it was like when I volunteered here. I mean, this street was nothing like it is today.

EM: So it was a lot of working-class people and poor people living in houses, old row houses that had been broken up, that were single-family homes in the 19th century, broken up into single room occupancy with bathroom, a bathroom on the hall.

BK: That’s right. There was a bathroom down the hall. It was a rundown, old, ramshackle building. So I would, I’d pass by here I don’t know how many times, because I was frightened, really, to go to work, to volunteer. I didn’t know what I would do. I didn’t know if I had any qualifications. I didn’t know what, what I would find. It was really sort of terrifying. And I didn’t know whether, who I would be seeing. Would I be seeing, you know, people, people with AIDS—PWAs, which of course that’s what we referred to when we start, I started volunteering. So, finally, I worked up my courage. I thought, you know, if I’m not gonna do it, who’s gonna do it?

———

EM Narration: Sandi Feinblum had walked up the steps of 318 West 22nd Street just a few weeks before Bill, fresh off a plane from San Francisco.

———

Sandi Feinblum: My friend’s name was Ramiro Medina. And he called and he was crying and scared and said, “I have this new disease, this new gay disease. And, um, can you come home and be with me? Can you move back?” And I immediately said yes.

EM: And, and what kind of care did your friend need when you got back to New York? What kind of shape was he in?

SF: He had, uh, PCP at the time, uh, pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. And so as he got sicker, which he did—uh, he died, um, much less than a year later—I wound up doing a lot of physical care for him, as well as helping him get through the system…

EM: Uh-huh. So you were, you were like his, his, his buddy to use the, the, uh, formal term that you used at GMHC for people who play that role.

SF: Right, right. I was like his buddy.

EM: Yeah. So, so what, uh, typically what a family member might do for someone who was seriously ill.

SF: Yes. Yes, absolutely. He was not out at the time, so he didn’t feel able to tell his family, um, and, uh, just wanted me to help him. He was family to me.

EM: Yeah. Uh-huh.

SF: Ramiro asked me to go to this place called GMHC, ’cause he was too terrified to go there himself and tell his status and ask anybody for information, ’cause they were the only place in town that knew anything about this disease. And, uh, I did, and this was in the little SRO on 22nd Street—and I listened to what was going on and I said I had a dusty old master’s in social work, did they need any more volunteers? And that was it. You know, everybody makes a choice, I guess. I made mine.

———

EM Narration: Alongside her full-time job caring for her friend Ramiro, Sandi picked up another full-time job. GMHC’s early management and founders took her to the Pines for the weekend—it’s a gay beach community on Fire Island near New York City—and they used everything in their arsenal to try to persuade her to become assistant clinical director of the fledgling organization.

———

SF: Uh, we had a great time. And, uh, it’s kind of, sort of a blur because that’s the kind of good time we had. I just remember being topless, dancing with Rafael Tavares, who was a psychiatrist who was on the board of directors at the time, out on the deck. [EM laughs.] And by the end of our few days there, somehow I had accepted the job, and it’s really a true story. [SF and EM laugh.] Um, they got me. [SF and EM laugh.]

And I honestly, I had said to myself that I would do it for a year. And I never wanted to feel like, you know, people during the Holocaust that didn’t do anything. I said, okay, I’ll give this a year. It’ll be over, and I will have done my part.

EM: When you say that you, that you thought it would be over in a year, what did you mean?

SF: It just didn’t seem possible that in New York, in the United States, they wouldn’t make some massive effort and find a cure. I was very naive in that respect.

———

EM Narration: GMHC matched volunteers like me with people who were sick and needed help. When I walked through the doors, I had a choice of being a “buddy” or a “crisis intervention worker.” Reading the application, I knew I wasn’t up for being a buddy. Now that I’d gone back into the closet for my new job out in Queens, there was no way to explain the absences being a buddy required.

I check the box to be a crisis intervention worker—a CIW. “Occasional visits required.” That I could do. I climb the worn, creaky wooden stairs to the intake interview.

———

EM: Do you ever remember interviewing anyone in the bathroom at the 22nd Street facility?

SF: I’m sure we did. [Laughs.]

EM: ’Cause that was my, thing is, that was my experience.

SF: Yes, I’m sure we did. Listen, we, we never had enough room or enough private rooms for anything. So I’m sure we did interviews in the bathroom. We did ’em anywhere we could.

———

EM Narration: I’m sitting on the closed toilet. My interviewer leans against the sink. She asks a handful of questions about what kind of experience I have counseling or working with sick people. I’ve just finished two years of training and volunteering as a peer counselor at a place called Identity House, where we worked with young LGBTQ people who came in off the street.

In short order, I’m scheduled for a weekend training, assigned to Crisis Intervention Team 12. And within a few weeks I’ve got the names, phone numbers, and brief descriptions of two clients: a 23-year-old Greek immigrant who was in the hospital, and a straight, early 30s drug addict who lived in South Brooklyn.

According to the notes, the gay guy, Efthimios, was sicker, so I went to see him first.

Efthimios was at St. Clare’s Hospital in Hell’s Kitchen, just north of where Doug and I had rented our apartment three summers before. I find his room, put on a mask and gloves, and open the door. Efthimios has a tracheostomy and is hooked up to a ventilator and a couple of IV lines. He’s wide awake, but he can’t talk because of the incision in his neck. I introduce myself, explain that I’m from GMHC, and that one of his colleagues at the diner where he works as a waiter called to ask for help.

Efthimios isn’t emaciated like I’d been expecting. He has meat on his bones and except for his thick brown hair that’s pasted to his damp, feverish forehead and the tube in his neck, he doesn’t look sick. He has pneumocystis pneumonia, and the only way to keep him alive is to force oxygen into his lungs while they try to get the raging infection under control. And who knows what else he has because when your immune system dies, you’re left defenseless and just getting scratched by a cat can turn into a fever that kills you.

I sit down next to his bed. I’m thinking about taking his hand, but we’ve never met before so maybe that’s too much? I look at him. He looks at me… and he looks terrified. Efthimios is my age, he’s gay, and he’s going to die. Just moments before, when I was donning the mask and gloves outside this hospital room, I’d felt proud of myself for overcoming my germ phobia, my abject fear of hospitals. But now inside the room, awkwardly perched next to the bed, all I really want to do is run, as far and as fast as I can.

I don’t run away. I don’t take his hand either. I don’t know what to do. I just sit there, in silence. With a young man I don’t really know but who could be me. Or who I could be. Who is very, very sick.

After a while, Efthimios picks up the pad and pencil that’s on the tray in front of him and writes a question. He holds up the pad: “Is there any hope?”

It’s not a question I want to answer. I’m certainly not qualified to answer it. But you don’t need to be a doctor to have a very clear idea of his prognosis. I don’t want to say what I think, so I lean on a cliché. “There’s always hope,” I say.

I tell Efthimios I’ll be back in a few days. As I get up to leave, another visitor arrives. He says hello to Efthimios and then asks me to step outside. In the hallway, the visitor explains that he’s only an acquaintance, that Efthimios had come to New York by himself from a small town in Greece where he couldn’t be gay. His parents are on a flight to New York. They don’t know Efthimios is gay or that he has AIDS. They only know that he’s sick and in the hospital.

I go back to the hospital a few days later. I don’t know if his parents got there in time. Efthimios’s bed is empty.

———

SF: In those early days you could not get supportive services. You couldn’t get welfare, you couldn’t get, um, food stamps because they didn’t consider HIV, uh, grounds for disability in the very early days. So, uh, people were losing their jobs left and right, and didn’t have money to pay their rents and were getting evicted and wound up in a lot of abandoned buildings when we couldn’t find any housing for them.

And a lot of times the buildings of course had no running water and no electricity. People had a crisis intervention worker and a buddy. Usually, uh, three or four buddies would take it on themselves to go to the abandoned building, and bring water and food, and clean, because often people were going to the bathroom in whatever facility was there, like an old bathtub or something—the toilets didn’t work.

And, uh, keeping them alive. Really. They w—they were the lifeline for those people. And there were a lot of them, and the city of course was ignoring it. And we had the highest number of AIDS cases in the world at the time. So you get the picture pretty clearly.

EM: That must’ve been enraging.

SF: It was infuriating. You know, um, I always said when white straight men can give it to white straight men, there’ll be a fast track. And of course we see with Covid that that’s absolutely the truth. Um, and, uh, unfortunately, uh, there wasn’t that same idea back then about gay men. And then of course not about IV drug users either.

EM: Yeah.

———

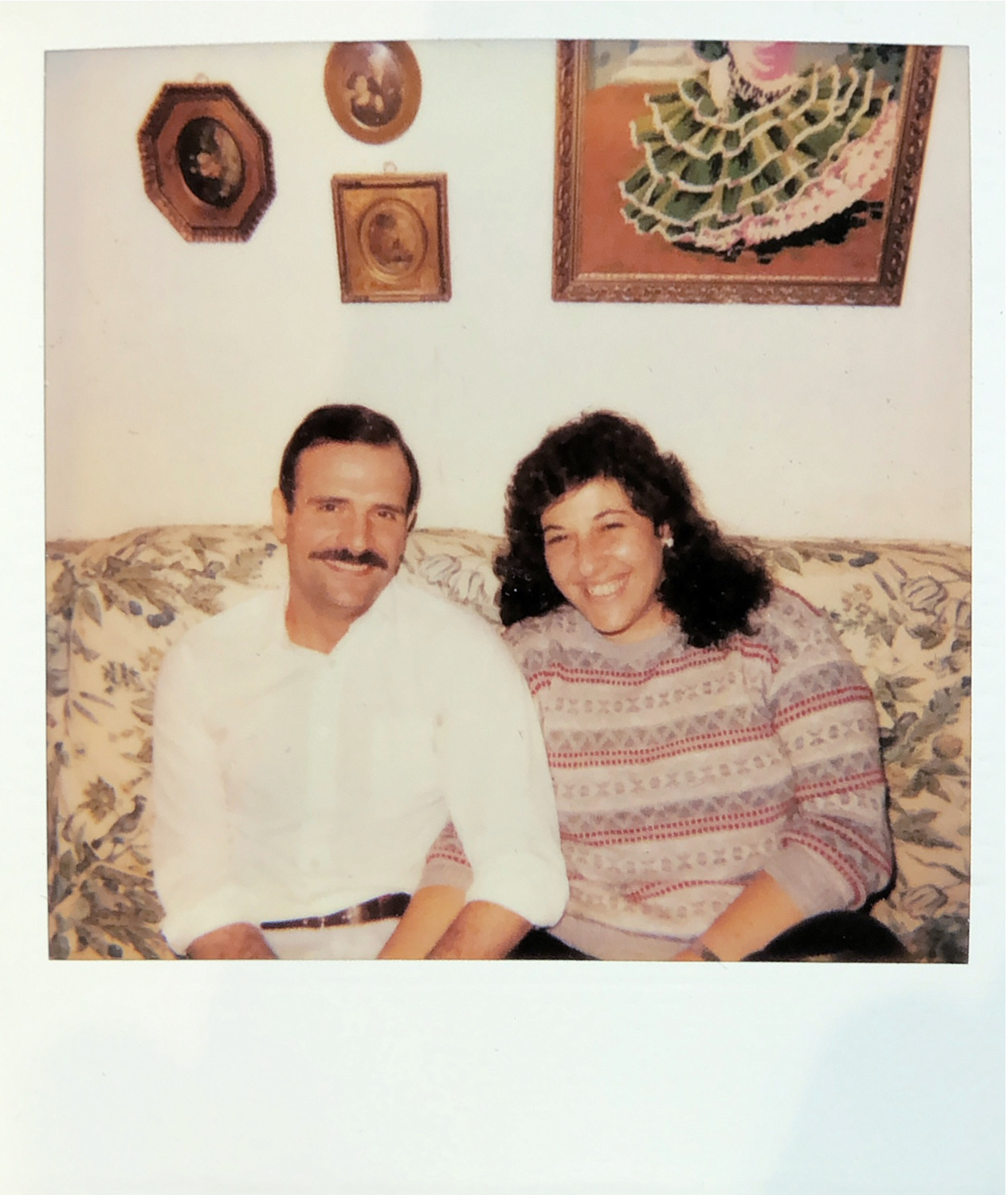

EM Narration: Getting to my other GMHC client’s apartment from our place on 81st and Lexington was a schlep. Jimmy lived by himself in a rundown apartment. The place was a mess, his kitchen table overflowing with prescription bottles and dirty dishes. Jimmy was twice divorced. His first wife was living with their 12-year-old son, Jamie, in another part of Brooklyn. His second wife, Laura, was still very much in love with him, but had to get out and create some legal distance as his behavior became more and more self-destructive.

———

EM: What attracted you to Jimmy in the first place?

Laura: Do you know when you look at someone and you just get smitten?

EM: Yes.

Laura: And, and I’m not like that, and, um…

———

EM Narration: Laura isn’t her real name. But for reasons that will become clear, she asked us to use a pseudonym when I managed to reconnect with her this past spring.

———

L: Jimmy was working as, you know, the daytime janitor/receptionist/security, all that. And we worked at that building. And then, um, one day, um, my friend Madeline said to me, “Oh, you know who’s really cute? Jimmy.” So I just looked at him. I was walking away, he was out there. I just, I remember this. He was washing the sidewalk, and I was like, wow. I remember that, and I remember the last time I saw him alive, when I waved goodbye to him in the hospital. It’s like, those are two images that always keep running through.

EM: What did he look like?

L: Jimmy was very good-looking. He was very built, you know—he had, like, the big muscles and stuff. Had the full head of hair, dark baby hair. He had his mustache, too. And, um, he just carried himself a certain way, and he had the blue eyes. Um, and, um, he, he was attractive.

EM: And you were smitten.

L: When I just looked at him like that, it was, like, I—and I’m, I’m really not like that.

———

EM Narration: By the time I meet Jimmy, in the apartment that Laura and a lawyer from GMHC had to fight to get him, the muscles are long gone. Jimmy is about my height, with prominent cheekbones, black hair, a mustache, and a pale complexion. We’re an odd pair. I’ve never met a drug addict before—at least not knowingly—and Jimmy isn’t the kind of straight guy who has gay friends. “I don’t usually like queers,” he tells me on my second visit. “But you’re okay.”

We talk a lot about Jimmy’s son, Jamie, and how Jimmy hates the thought of leaving him without a father. Jimmy knows other addicts who’ve died and he has no illusions that his story will be any different. I tell him that my own father died when I was 12. He asks what happened. And I tell him what I don’t usually tell anyone, at least not then, that my father killed himself.

Over the coming months, I visit with Jimmy several times. He’s in and out of the hospital, and Laura says his treatment was horrifying.

———

L: Oh, the things that they used to do, um, when they were sending him out and they weren’t giving me his medicine, it wasn’t there or whatever, and I said, “You know, he’s a dead man without,” he goes, he said to me, “Well, he’s a dead man anyway.” The fuck? You have a doctor saying this crap to you? Come on now. It was just like he’s nothing to them. It’s nothing. It’s just a piece of—

EM: And you still loved him.

L: Yeah. He was, um, like no one ever, like, it was almost like he was my child. I can’t explain it, but it was that kind of thing. It was—

———

EM Narration: I get a call from Jimmy that he’s in the hospital, downtown at Beth Israel. Can I come see him. He’s thinner, weaker, and even more pale than our last visit. He’s on an open ward that reminds me of a drawing from the Madeline books where all the little girls are in beds lined up in two rows.

Jimmy sits on the side of the bed and supports himself with his stick-thin arms, an IV in the top of his right hand. That’s where they could find a vein. I sit in a metal folding chair facing him. We talk about his funeral. I haven’t planned one before. He asks me if I can give the eulogy. I figure if he’s asking me there’s no one else he can ask, so I don’t object.

———

EM: So we talked about his eulogy and I had some suggestions because I had been a 12-year-old boy and he had a 12-year-old boy. I’d been a 12-year-old boy who sat in a funeral home, um, when people gave eulogies of my father and never mentioned me. So I said, “Let’s make this about him,” and… It’s terrible, I can never talk about this without remembering being that 12-year-old in a funeral home in Forest Hills, Queens, with my, at my father’s funeral. Um, so we talk—I asked him about what he thought he might like to say to his kid, what he would want his kid to remember. And I had some suggestions about how, um, uh, how much he loved him, and how much, how sorry he was that he wouldn’t get to be with him as he grew up to become a man. And to become a better man than he was, because he was worried about the example he was setting for his son, having been a drug addict, having gotten AIDS, and was, was ashamed, um, and was divorced, um… And so we talked about what, what would be in the, uh, the eulogy. And, um, I left him that day and I never saw him again.

———

L: He died in 1984, December.

EM: He was at Beth Israel, am I, am I remembering correctly?

L: Yes.

EM: Yeah. Did he die at Beth Israel?

L: Yes. I was going to take the time off to be there all day with him. We were gonna get him spruced up, Jamie was gonna come visit. I was gonna get him spruced up and was gonna be there, you know, going through memories, doing this and that. This was the, my last full, you know, day of work. And I went there and I was telling him the things we were gonna do, you know…

EM: But you didn’t get to do that with him.

L: Spend all that time? No, so you beat yourself up, like, why didn’t I before? But it’s when they said he’s not gonna have much longer, I was taking a leave so I could be with him. Um, and that’s, and I never got to do that. And I just remember, like, leaving, like, looking back, and I’m going like that—“I love you”—and that’s… Just like I remember him out there doing the thing and turning around and waving, it’s just like, you know…

EM: So you remember him turning around and waving to you when he was cleaning the sidewalk. And you remember waving to him goodbye that last time.

L: Yeah, and saying “I love you,” yeah.

EM: But you didn’t think that was the last time you’d see him.

L: No, I was, I was making plans, and then I get, after I’m home, like, an hour, I get the call.

———

EM Narration: Redden’s on 14th Street was the one funeral home in the city that didn’t hesitate to take people who died from complications of AIDS. Jimmy wanted a Catholic funeral and thankfully the church across the street from Redden’s, St. Bernard’s, has no objections to hosting a service. It wouldn’t be their first for an AIDS patient, and certainly not the last.

The church is mostly empty. But that doesn’t matter. At least not to me. The eulogy I deliver is for that boy in the third row who needs to hear how much his father loved him and how much he wished he could live to see him become a man—to help him become a better man than he was.

———

L: It’s funny, my boss at the time, when he died, she goes, “Oh,” she said, “Oh good, now you can go back to your life.” She later apologized for that, but people just didn’t understand.

———

EM Narration: After Jimmy died, I called it quits from GMHC. Over the years I’ve developed this story that I told myself that by the time my clients died, some of my friends had gotten ill and I got busy looking after them, and that’s why I stopped volunteering at GMHC. And it’s true that one of my college friends had gotten sick, but that’s not why I walked away. Ran away.

The truth was, it was too much for me. I gave Jimmy’s eulogy a day after the 14th anniversary of my own father’s death. Jimmy’s death, that 12-year-old fatherless boy—it was too much. I got really depressed. Not a good thing for the child of someone who killed himself. I admired the people who took on AIDS patient after AIDS patient. But I couldn’t. I felt guilty that I wasn’t one of them, even ashamed. But I wasn’t one of them.

While I counted my time with the Gay Men’s Health Crisis in months and only had two clients, Bill Kux and Sandi Feinblum spent years at GMHC. Bill worked as a volunteer for eight years in a variety of roles within the intake department, ultimately becoming an intake clinician, helping hundreds of PWA—people with AIDS. Sandi worked on staff at GMHC for a total of seven years and was deputy director by the time she left to work as a consultant to other AIDS organizations and to focus on her psychotherapy practice.

Back in 1984, I wanted to push the growing AIDS crisis far into the background, but of course there was really no running away, especially as AIDS became all too real for people close to us.

Still, Barry and I did get away. To the Caribbean. Our first real vacation. But even there, there was no getting away. Next time.

Postscript. My memories of Jimmy and Laura and how their lives were upended by AIDS are memories. In the past. I never take for granted how privileged I am that HIV/AIDS is not part of my everyday life. But that’s not the case for Laura. And, as I said, Laura is not Laura’s real name. She asked us not to use her real name because almost no one in her life knows about her past, including the son she had with the man she married after Jimmy died.

———

EM: You asked me, um, one of the first things you asked me was, “Do you think I’m in danger? Do you think I could be sick?”

L: Oh.

EM: Why might you have asked me that?

L: I, I, I, because I, there was a possibility, but I don’t know whether by the time I met you I was already in the, enrolled in the CDC study.

EM: Ah. In ’83—there was no test yet in ’83.

L: There was no test, but so they steered me, um, to a, uh, a study that I became part of. That’s why as soon as they got the test, I found out that I was.

EM: That you were…?

L: Positive. Yeah. ’Cause I had my blood stored. So I found out the beginning of ’85.

EM: What did you think when you got that news?

L: Um, you know, what, what you think is the, the shame, the, you know, first of all, you think you’re going to, you don’t have much, you’re going to go through this horrible sickness. You’re gonna be shunned the way that he was. It was really terrible, um, at the hospital and stuff, the way he was treated. Um, and that I didn’t want my family to go through that.

Um, it was just thinking about what I was going to do about it. You know, how I could do away with myself if things got bad, because I didn’t want people to know, I didn’t want my family, my—only my sister knew at that point. So it’s, it’s not like, oh, it was cancer and whatever—it was this thing. And, um, so it was very, very, very hard, um…

EM: You’re a long-term survivor, I imagine that you have been studied.

L: Um, no, after I finished those, the last study was, uh, like, that I was in, I think it finished, like, in ’94 or ’95. No, no one’s ever studied me after that.

EM: Are you surprised you’re still alive?

L: Well, now I’m not, but I, I was, and I, I know that there are certain things that have been affected by the drugs that I’ve had to take. I had to have, um, a hip replacement, and it wasn’t arthritis. It was this weird thing that when you looked up, they said they didn’t know whether it was the drugs or that itself.

Um, and I have osteopine, which, uh, there’s no one that, no one in my family—you know, it’s all strong bones—and I, I know it’s, it’s that, so it’s, you know, things like that have, uh, affected me, but otherwise, um, I’ve been very, um, you know… Well, I’ve had, I’ve been hospitalized with pneumonia twice. Let me just stop myself here. [L and EM laugh.] Just gonna brag about… [L and EM laugh.] Um, I think one of the things that helps me a lot is, um, that I, um, exercise is what makes me feel the best.

EM: Has it gotten easier to talk about your HIV status?

L: I never do.

EM: You don’t.

L: No.

EM: Did you ever tell your parents?

L: No, that was something I wanted to, um, you know, keep away. Why cause people pain?

EM: Right. And your son doesn’t know.

L: No.

EM: How come?

L: Um, it’s, trust me, it’s better that way. Um, and, uh, yeah, I don’t know. He doesn’t need to know.

EM: Do you look back now on your life and wonder how you, how you did this, how you survived and, and built a family and a career and you made it to 67? It’s really remarkable.

L: Um, just by… You know when you feel like, it’s like the thing, like, you know, you lose something, you just keep going on—do you know what I mean? You just keep moving and moving forward so that… When I would, I remember when I would read things about people who were positive and they stopped working. And even though they were, you know, didn’t have, and I’m like, what the fuck? Do you know what I mean?

EM: Mm-hmm.

L: I know that the prognosis at the time wasn’t the greatest thing, but what the hell? You just keep on going, you know? There’s nobody who’s gonna support me and, you know, so you just keep going and moving on.

———

EM Narration: Laura’s story of survival is made even more remarkable when you consider the way women were treated—or not treated—in the early years of the AIDS crisis. Although the CDC first published that women were contracting AIDS from their sexual partners in 1983, the agency would remain silent, releasing little information for women for years. Women were excluded from the clinical definition of AIDS until 1993. AIDS often didn’t look the same in women as it did in men. The symptoms and illnesses used for the clinical definition were based on the disease’s progression in men. For years, many women didn’t show up in the official numbers, and were prevented from accessing treatments and benefits. Women were also excluded from clinical trials with language such as “no pregnant women and no non-pregnant women.” And, racial disparities intersected with sexism to deadly effect: by 1989, AIDS was the leading cause of death among Black women ages 15 to 44 in New York State and New Jersey.

———

Many thanks to our hard-working crew at Making Gay History, including story editor Sara Burningham, assistant producer and sound designer Rae Kantrowitz, deputy director Inge De Taeye, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, genealogist Michael LeClerc, and our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. This season was recorded at CDM Sound Studios. Special thanks to interviewer-slash-oral-historian Shane O’Neill and our listening circle, including Syd Baloue, Cheryl Furjanic, Dr. Jamila Humphrie, Ann Northrop, Benjamin Riskin, Jenna Weiss-Berman, and Mike Winerip.

Thanks also to Bill Kux, Sandi Feinblum, and Laura for sharing their memories.

Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers, with additional scoring by Rae Kantrowitz.

This season of the podcast was made possible by the generous support of the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, the Calamus Foundation, the Kipper Family Foundation, Andra and Irwin Press, Jeff Soref, Kevin Williams, Kathy Danser, Hal Brody and Don Smith, and scores of other individual supporters.

“Coming of Age During the AIDS Crisis” is a production of Making Gay History.

I’m Eric Marcus. So long, until next time.

###