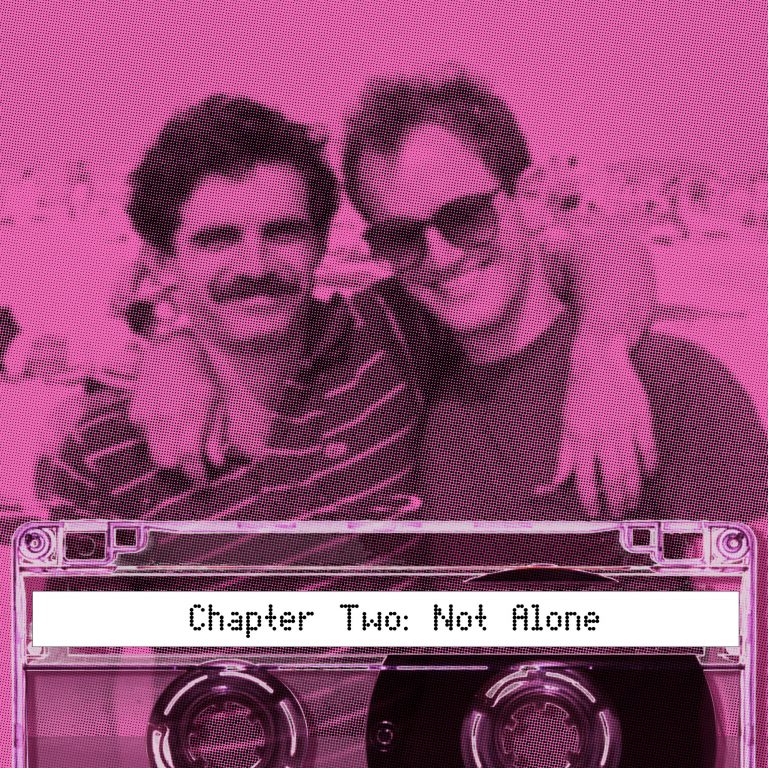

Coming of Age During the AIDS Crisis — Chapter 2

Episode Notes

Even as the epidemic spreads, a rousing AIDS fundraiser at the circus, a new boyfriend, and journalism school combine to bring joy, a sense of community, and purpose into Eric’s life.

———

For a comprehensive overview and useful links related to HIV and AIDS, consult this HIV.gov timeline.

For a New York City-specific timeline, see this New York magazine article. (Please note, however, that the Patient Zero theory referenced at the top has since been discredited; for more information on the subject, watch the documentary Killing Patient Zero.)

This chapter covers April 1983 to the spring of 1984. According to the Centers for Disease Control, by the end of 1983 there were 3,911 reported cases of AIDS in the United States. There had been 2,473 deaths. The first half of 1984 saw 2,093 more cases and 822 more deaths. Because there was no test for HIV at the time, the actual numbers are unknown.

For many in the gay community, 1983 was a turning point as the AIDS epidemic continued to grow. On March 27, Larry Kramer published “1,112 and Counting,” his famous call to arms, in the New York Native, a gay newspaper. By contrast, the mainstream press’s early reporting on the epidemic was marked by confusion or indifference. To get a sense of the mainstream broadcast media’s coverage of AIDS over the course of the disease’s first ten years, go here.

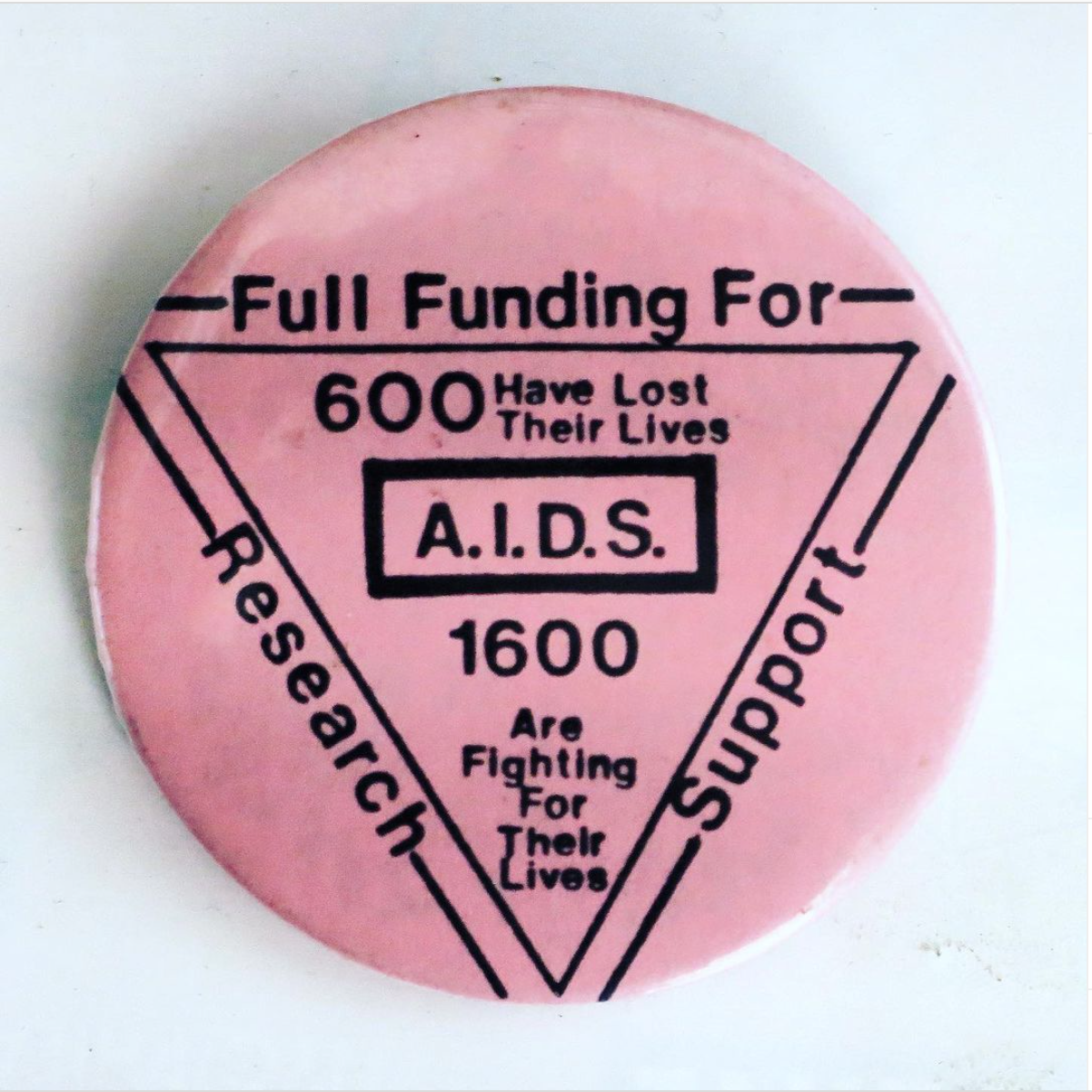

Government inaction and social prejudice left gay people to fend for themselves. They pooled their resources to advocate for funding, research, and medical services and to provide health and educational services directly. Starting in 1982, these community efforts led to the founding of organizations that included, among others, the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) in New York City, the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, and the AIDS Action Committee in Boston.

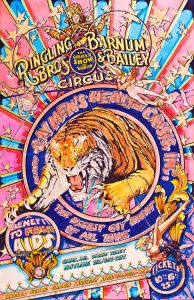

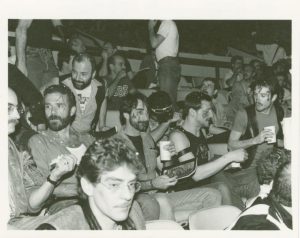

In the episode, Eric reflects on the GMHC-sponsored fundraiser he attended on April 30, 1983, featuring a benefit performance of the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus. It was the first community-wide fundraising event for AIDS in New York City. (Los Angeles had its first major AIDS fundraiser just a few months later.) Read how the circus fundraiser came together in this Philadelphia Inquirer article about GMHC, published in the run-up to the event. (Find out more about GMHC in the episode notes for the third chapter of “Coming of Age During the AIDS Crisis” here.)

Richard Dworkin, boyfriend of the late AIDS activist and musician Michael Callen (see below), preserved footage of the GMHC circus event, which can be viewed on his YouTube channel—e.g., “The Star-Spangled Banner,” conducted by Leonard Bernstein and sung by mezzo-soprano Shirley Verrett; the opening speech by Mayor Ed Koch; and a backstage interview with Mayor Koch. The footage was shot by Quentin Scobel and his boyfriend Rand Snyder as part of an unfinished documentary on the early AIDS epidemic. Both died of AIDS-related complications in 1996.

In May 1983, activists in New York City and San Francisco held coordinated candlelight marches, led by people with AIDS. Watch footage of the San Francisco march here. The demonstrations marked the first time that people with AIDS came together in public to demand action and to humanize the disease. In June, activists with AIDS—including Bobbi Campbell, Richard Berkowitz, and Michael Callen—wrote The Denver Principles, a manifesto for the community as well as a Bill of Rights for those with AIDS. It began, “We condemn attempts to label us as ‘victims,’ which implies defeat, and we are only occasionally ‘patients,’ which implies passivity, helplessness, and dependence upon the care of others. We are ‘people with AIDS.’” The Denver Principles empowered people with AIDS nationally and affected healthcare forever.

The episode features audio from a segment on promiscuity in the gay community taken from Vito Russo’s Our Time, a program for the gay community that ran on public television station WNYC-TV in 1983. Vito Russo’s introduction can be viewed here, Charles Jurrist’s statement here, and Michael Callen’s response here. Most of the 13 episodes of Our Time are available here.

Find out more about the life and legacy of film historian and activist Vito Russo in this Making Gay History episode and the accompanying episode notes. Learn more about activist and musician Michael Callen in this in memoriam segment from In The Life or read the recently published biography Love Don’t Need a Reason: The Life and Music of Michael Callen by Matthew J. Jones, reviewed here.

Discussions of promiscuity in the gay community invariably included the subject of gay bathhouses. For a concise overview of their history, from Victorian times to the AIDS crisis, listen to this episode of Dig: A History Podcast. For personal accounts of the bathhouse experience, read this Michael Callen piece or watch this video testimonial of a formerly closeted man who lost his virginity at the baths. For a deep dive into the bathhouse controversies of the early AIDS years in New York City, have a look at this thesis; for an overview of how the issue played out in San Francisco, read Randy Shilts’s seminal And The Band Played On.

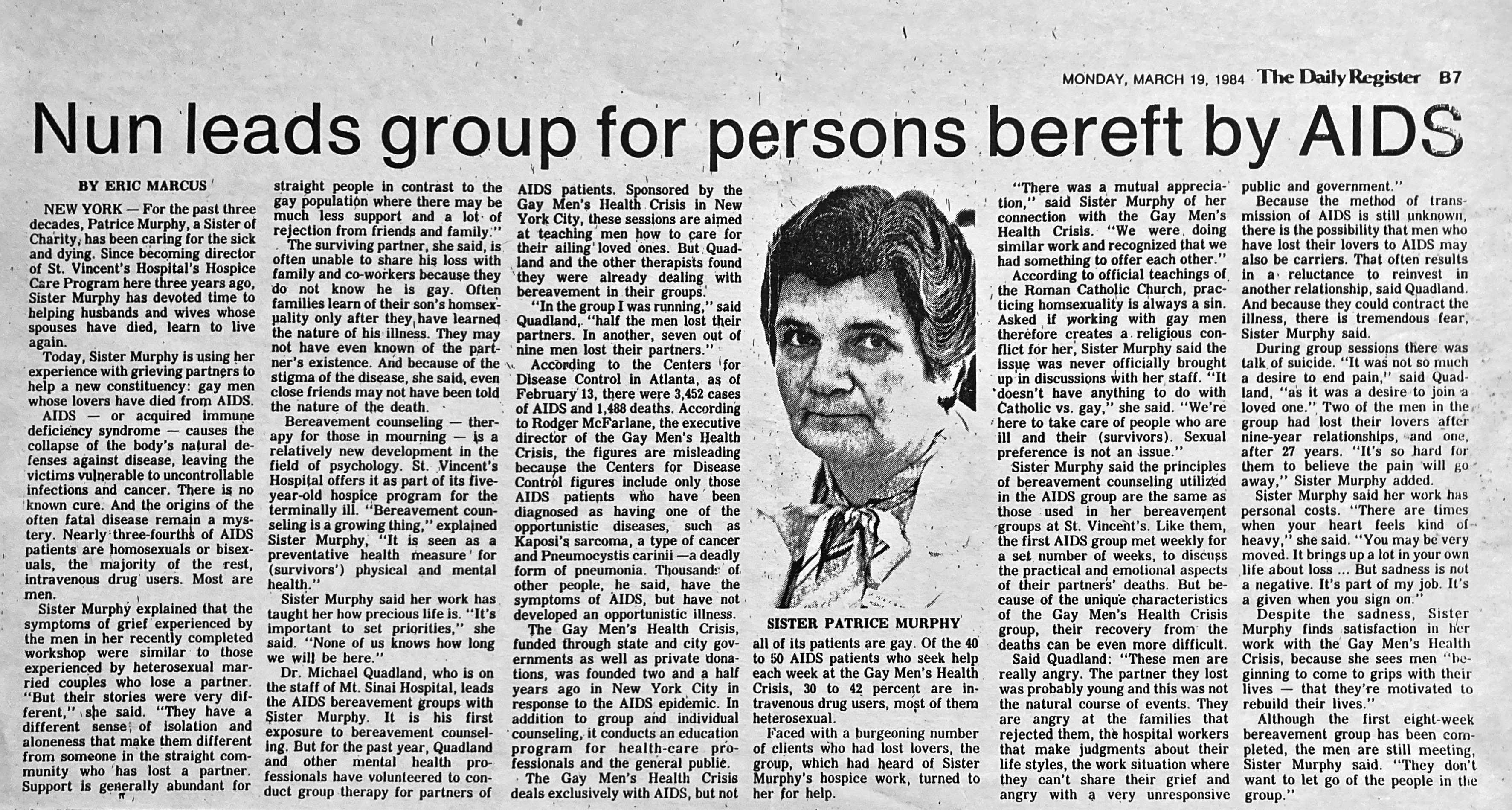

While attending the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism , Eric wrote an article (see below) about a nun who ran a counseling unit for gay men who’d lost their partners to AIDS at New York City’s St. Vincent’s Hospital. The Catholic hospitals St. Vincent’s (in Greenwich Village) and St. Clare’s (in Hell’s Kitchen) loomed large in the early years of the epidemic in the city due to their early willingness to treat AIDS patients, their pioneering creation of AIDS units (from which they profited greatly), and their proximity to Manhattan’s gay enclaves—although the relationship between the Catholic Church and the gay community was, to say the least, fraught.

Hear what it was like to work at St. Clare’s during the 1980s from former medic Maggie Dubris here. Learn more about how the epidemic and the Church intersected in the podcast Plague: Untold Stories of AIDS & the Catholic Church.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus. Forty years ago, news first broke into the mainstream of a deadly new disease. I was coming of age and coming out in New York City during the first years of the AIDS crisis. Friends and neighbors fell ill and died, our community was changed forever. This is an audio memoir of that time. It’s a record of my experiences between 1981 and 1988, and a journey to connect with some of the people who went through it with me.

By the start of 1983, the Centers for Disease Control reported that 1,221 people had been diagnosed with AIDS in the United States; 748 had died. Many thousands more had symptoms that would prove to be the early stages of the disease.

At the start of 1983, I was lonely. I was single and I didn’t want to be. I didn’t feel a connection to any of New York City’s gay communities. And I hadn’t yet found a professional community. I didn’t belong. But I longed to.

This is chapter two: “Not Alone.”

———

Announcer: … proudly present the 113th edition of Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus’ “The Greatest Show on Earth”!

———

EM Narration: It was my first time at the circus. April 30, 1983. Madison Square Garden. I’m 24 years old. And I am not on a date. Barry is not my date yet. We haven’t fallen in love yet. But we are at the circus together.

We’re at the very first big AIDS fundraiser in New York. A few early supporters of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis got together and bought out a performance of the Barnum & Bailey Circus. The greatest show on earth wasn’t prepared to officially host an event for this cause, but GMHC got around that by reselling the 17,600 seats to raise money and tackle the growing crisis.

We’re in a sea of gay men. When the ringmaster introduces Broadway star Patti LuPone, we lose it.

———

Announcer: Patti LuPone!

———

EM Narration: After a moving speech from Patti, Leonard Bernstein walks across the floor of the arena to conduct the orchestra for “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Mezzo-soprano Shirley Verrett’s voice fills the Garden, joined by thousands of voices in the audience.

———

Shirley Verrett: (Singing) … shall wave / O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

———

EM Narration: Patriotism, clowns, and AIDS. Seems improbable now, but felt so right in the moment.

———

Hal Moskowitz: Word spread like fire. And who doesn’t want to go to the circus?

———

EM Narration: Hal Moskowitz started volunteering for the Gay Men’s Health Crisis in the spring of 1983. His first job was helping to distribute tickets for the circus night.

———

HM: At the Garden, the buzz was electric. There was a lot of cruising. There were quite a number of drag queens. I didn’t go into the men’s room, but I know people that did, and it was quite busy. It was a tearoom. And when the show started, the Ringling Brothers performers were a little bit in shock, and you could see it on their faces, because we were cheering things that they never got cheered for before, like a headdress and a costume. And it took on a life of its own.

There was also the fact that we knew that we were there to see a performance, but we were doing something bigger. The money that we paid for the tickets was for us. We knew that from this, we were going to be able to do other things.

EM: What did you take away from that experience of seeing this community come together in a way I don’t think it ever had before.

HM: That we weren’t alone. That I wasn’t alone. I mean, I, truthfully, I have never been that frightened in my life. Because, by then, people were having symptoms, not saying anything to anybody about their symptoms, because they didn’t want anybody to know. They would wake up on a Monday, arbitrarily, with symptoms that felt like a cold was coming on. By Monday night they, they had fever. By Tuesday morning they couldn’t breathe. By Wednesday they were dead. It was that quick. And we were going, we, and we couldn’t find funeral home, uh—

EM: I remember.

HM: Everybody knew that they bought the ticket to raise funds to figure out what the hell was going on, because nobody would listen to us. The hospitals, the doctors, nobody. We were helping ourselves. It wasn’t like, I’m out, I’m proud, here I am, get used to it. It was like, here’s my five dollars, use it for me and everybody else. And we were happy to be together. Most people were concerned about what was happening. They were thinking about what was happening. They were mourning, they were frightened. They were sick. But this was the first time we were all in the same place.

———

EM Narration: The show of solidarity in the fight against AIDS, the visibility, the sheer numbers—it felt groundbreaking. The city’s mayor, Ed Koch, was there, and he promised help was on the way.

———

Ed Koch: The fact is that at the moment there are about 1,200 detected cases—600 of them in New York City. And of the 600, about 140 are people who are in municipal New York City hospitals. We have to find the cure, and we have to find it quickly.

———

EM Narration: What will stay with me forever about that night at the circus is, for the first time, being in an arena packed with people like me. I’d never felt connected to the gay community like that before. It was a feeling of belonging, of coming together to face something terrifying—with joy.

When I looked in the New York Times the next day to see what had been written about it, there was nothing. Not even a ripple in the mainstream consciousness. Something that felt so big and still feels so significant sank without a trace. Ask anyone who was there that night, we remember it. Crystal clear—17,600 of us. And me. And Barry.

Barry and I had been colleagues at the Ziff-Davis Publishing Company for the past couple of months. I liked Barry right away and figured he was gay. I didn’t ask. He didn’t tell. But I knew. I wasn’t smitten, not even a hint of a budding crush, but I did look forward to seeing him each day. He was charismatic, a bit goofy-looking— tall, thin, and gangly—sort of like a human Gumby. A brilliant smile. The best teeth of any human on the planet.

Barry was also a rube—a very charming rube. Totally clueless when it came to life in the big city. He was from a small town in the Central Valley of California, a one-time forest fire fighter. Barry had six years on me, but as the native New Yorker, I happily took on the role of urban mentor.

I arrived at Ziff-Davis at a crazy moment of explosive growth in computer publishing. And before long I was promoted from a temp to start-up managing editor on a series of computer magazines. We were surrounded by wires-and-pliers guys—computer hardware really got them going. But Barry cared as much about computers as I did, which is to say, not much. We loved writing, and found the work thrillingly creative, despite the subject matter.

My first experience of falling in love had been like a baseball bat to the head: instant. With Barry there was no baseball bat. It was a slow burn—so slow, in fact, that when my friend Libby extends an invitation in late July of 1983 to spend the weekend at her family’s beach house on the North Fork of Long Island, I tell myself that I’m asking if I can bring Barry because it’ll be a chance to show him a very different side of New York. Just an extension of my New York tour guide duties for the California country bumpkin.

Libby’s invitation had been for me. I tell Libby that Barry is new to the city and she says, “Of course, he can come, too.” I say nothing about Barry being gay. I say nothing about me being gay. It just seemed easier that way. Well, I was afraid of how Libby might react. Not that I had any specific reason to think she’d react badly, but I was always afraid.

If you can imagine the perfect summer cottage in the perfect beachy setting, that’s the place Barry and I pull up to in our rental car on a Saturday in late July 1983, the seashells and the sandy dirt driveway crunching under our wheels. Libby’s family’s beach house is nestled in pine trees on a bluff overlooking Peconic Bay, with a screened-in porch running the length of the cottage, enough rocking chairs for a dozen guests, and well-worn board games piled high on rattan coffee tables.

We change into bathing suits and T-shirts, and the three of us head down to the dock, and Libby’s little Sunfish sailboat. As we crawl on board, I say a prayer to myself: please don’t get seasick. I’m so hypersensitive to motion that once I got seasick on a pedal boat, mere feet from the shore. We’re out on the water for more than an hour. I successfully avoid seasickness, but not sunburn.

So when Libby’s dad calls to us from the dock taking drink orders, I’m ready for a gin and tonic and a shady spot on dry land. Barry and I exchange a glance. More than a glance. When you know, you know.

———

EM: And then we started dating each other seriously in July of ’83. And we couldn’t tell anybody at the office that we were having a relationship. So we would take the subway to work together and then go out different exits of the subway, or wait a little while—one of us would wait downstairs—and not go in together. Because we were afraid to tell our boss—we had the same boss.

We came clean within a couple of months, um, but it was that whole pretend—um, glancing at each other at the office, and leaving something on his desk for him. I left him a little container of watermelon—I knew he loved watermelon. It was all, it was all very sweet.

And then when we told our boss, he and his wife were so totally supportive—embraced us, invited us out for dinner, had us to their apartment. They couldn’t have been more wonderful to us, which was so affirming, uh, to be this young couple in a time when everybody said a relationship between two men couldn’t last. And I was determined—determined—that this relationship would last no matter what.

Shane O’Neill: For better or for worse?

EM: For better or for worse.

———

EM Narration: Ever since that first article in 1981 about the rare cancer, I kept looking to the New York Times for reporting on the AIDS crisis. Slim pickings. Like I said, there had been nothing on the GMHC event at Madison Square Garden. In fact, it wasn’t until almost two years into the epidemic that AIDS made it onto the front page of the Times. Even now it shocks me how little information was in the mainstream back then. How little AIDS was covered. How invisible LGBTQ people were when it came to the news media.

But despite that, I wanted to work in mainstream media. I loved writing, I loved asking questions. I loved being published. I loved Barry, but I didn’t want to work in computer magazines forever. I had enough money for one year of grad school thanks to veterans’ benefits from my dead father. So I headed to Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism. I was totally unprepared for what breaking into mainstream media meant for someone like me. Thankfully, I wasn’t the only one.

There were a hundred students in my class at the J-School. Two of us were out. It was such a relief when Stuart and I spotted each other stepping on board the Circle Line ferry, the semester’s inaugural event, the night before classes started.

———

EM: How did we spot each other? Because I remember thinking, oh, the other gay guy in the class. Um, I don’t know if you saw, thought the same thing.

Stuart Schear: Yeah, you know, you had sort of that neo-preppy gay look of the time that no longer really exists. And I thought, oh my god, there’s another gay guy.

———

EM Narration: Right off the bat, a dean warned me that being out could ruin my career prospects, and leaving J-School with a clip file full of stories about the gay community or about AIDS would make it impossible to get a job in mainstream journalism. I heard him loud and clear, but when Stuart came up with an idea for a short film about AIDS for a documentary class we were taking, I jumped on board.

———

SS: I picked a topic that had actually not gotten a lot of coverage yet, which is how are gay men changing their dating behavior and sexual behavior, um, in the context of HIV/AIDS and the threat that it presented to their health.

EM: My memory is that the two of us wanted to be on the same team working on this piece and that the lead professor objected, had said that the two gay guys couldn’t be on the same team, and I wound up dropping the class.

SS: You know, now that you mention it, I do recall that—that we had talked about that and that happened. I had entirely forgotten about that.

EM: Yeah, I was, I, I was really keenly interested in doing documentaries, but I was very disappointed, and I don’t, I don’t remember pushing back in a big way then, um, but he was firm about it.

———

EM Narration: Since the film had been Stuart’s idea, I bowed out and dropped the class. Stuart pressed on with the project.

———

SS: We received so much negative feedback, and I, I would characterize it as harassment from both professors. So one professor said, “You say that you’re reporting on the gay community. What is the gay community? I don’t even know if it exists. Can you prove that a gay community exists?” He also asked, which was really so shocking, “When we talk about the gay community, are we also including the Nazis who were homosexual?” The other professor, she warned us strenuously that we were at risk for becoming ill if we worked on this project, that we would be close to people with HIV/AIDS, that we might be in laboratories, and that we would be putting ourselves at risk.

———

EM Narration: Despite being bullied out of the documentary class, I managed to tag along with Stuart for one early-morning shoot at a bathhouse, which was wild because the bathhouses were under intense scrutiny at the time. But the manager of a gay bathhouse on East 56th Street let us in to film. It was an important story to tell. Aspects of gay life were being changed forever. And plenty of people were not happy about it.

The bathhouses were at the center of a fierce debate in the community about how to handle the crisis. How to live our lives in the new reality. The videotape of the short documentary film I helped Stuart make is long gone, but I’m going to play a segment for you from a public TV show from around the same time that lays out the conflict that was playing out in bedrooms and bars and bathhouses around the city.

Vito Russo, one of my heroes of the movement, was hosting a show for and by the gay community called Our Time. He’s joined by Charles Jurrist, a writer for the gay newspaper the New York Native, and Michael Callen, who’d been diagnosed with AIDS and became an activist.

———

Vito Russo: The issue of promiscuity is a really hot issue surrounding the question of AIDS right now. There’s been an ongoing and often heated debate about the relationship of sexually transmitted diseases and promiscuity and the gay male lifestyle in the ’70s and ’80s. And we’ve decided to invite two people who for the past year and a half have been debating this with their friends and writing about it in the gay press, and have them air their views in point/counterpoint. First, Charles Jurrist, uh, will have his say. And then I’ll introduce Michael Callen, who will do a counterpoint to his discussion.

Charles Jurrist: I’m a gay man. It took me years to bring myself to say that openly and with pride. Certainly, my sexuality is only a part of my gayness, but it is the central part. If I can’t join another man’s body to mine, then how am I gay? Liking Bette Midler isn’t enough. Make no mistake, I know about this disease, and I know it may strike me tomorrow. I’m scared.

The crucial question is, how will I let my fear affect me? I know what I won’t do. I won’t give up the physical expression of intimacy. And in my sexual encounters, we won’t start out with a health quiz, nor will we limit our lovemaking to certain acts. I refuse to treat my partner as a sick person or to present myself as one. To give up sexual communication out of the fear of physical illness and death is really to embrace another kind of death: the death of wholeness, the death of the spirit—in fact, the death of the self.

VR: Next our guest Michael Callen, who is one of the founders of a group called Gay Men with AIDS, will reply to this point of view.

Michael Callen: Promiscuity is a vague word, which means different things to different people, but until we develop a better vocabulary, promiscuity remains the best word we have to describe the historically unique phenomenon of large numbers of urban gay men who have large numbers of different sexual partners in such commercialized settings as bathhouses, backrooms, bookstores, balconies, meat racks, and tearooms.

To those who wake up every morning and examine their bodies for KS lesions, to those who have seen friends and lovers and former tricks waste away like victims of Auschwitz, disfigured by disease, urban gay male promiscuity as we know it today has no defense. The political issues raised by promiscuity are important, but what civil rights do dead men have? As long as we continue to selfishly ask, “Is that man a health risk to me?” without first asking, “Am I a health risk to him?” we will never be free from the tyranny of AIDS.

———

EM Narration: Like Michael Callen said, promiscuity did mean different things to different people. I have a correction to make. Last chapter, I said I’d slept with maybe 20 people by 1981. Well, that was an undercount. Dredging deeper through my memories in the small hours of a sleepless night recently, I counted up to 39, and I’m afraid even that number may not be definitive. But still, I didn’t consider myself promiscuous. The only time I’d ever been in a bathhouse was to film that documentary with Stuart.

Even though Barry and I had stood shoulder to shoulder at a packed Madison Square Garden, listening to the speeches at the GMHC fundraiser about a clear and present danger, an epidemic that was coming for all of us, we didn’t talk about our sexual history, and we didn’t talk about how we’d keep each other safe. Years later, we’d rack our brains to remember details of what we’d done in those first heady days and weeks together. Not out of nostalgia—out of fear. There were no safe sex guidelines for us to follow then beyond what the experts were telling us at the time: have fewer partners. We were doing that. We had found each other. And we made a commitment to be monogamous.

———

Shane O’Neill: So, 1983—it’s, like, the beginning of, like, this huge shift in consciousness about AIDS and sexual health. You’re also starting your career. You’re at journalism school. You’re also starting this relationship with Barry. Were you feeling overwhelmed? Like, what was your state of mind? Were you thriving on the chaos or thriving on the activity?

EM: I was, I was so happy in 19—the fall of 1983. It wasn’t even journalism school. I was so happy to be in a relationship with someone I loved who loved me. We were crazy for each other. Um, in some ways both lost boys—his mother had just died, I had this terrible backstory. And I had always wanted a, a, a home, and we made a home together, and the AIDS crisis was not going to get in the way, and even classes didn’t get in the way. I was really focused on making this home with, with Barry and having a relationship and being happy and, and not letting anything get in the way of that.

———

EM Narration: Falling in love, moving in together, stripping 10 layers of paint off the ancient baseboards in our tenement building bedroom, and installing beige wall-to-wall carpeting—100 percent wool. It was all I ever wanted. Making a home together. To love and be loved.

Despite stuffing my fears and anxiety about the AIDS crisis into a box, a box separate from the life I was trying to build with Barry, I couldn’t totally ignore or suppress my need to know more about AIDS.

———

EM: Um, I’m holding in my hand my clip file, and I did the cover story for New Brooklyn Magazine, Staten Island Magazine, …

———

EM Narration: At home in Chelsea, recording my oral history with my friend, video journalist Shane O’Neill, I pulled out my clip file, the folder where I collected all my early articles and publications.

———

EM: I came to see that I had something to say, um, and I liked asking people questions, and I liked the writing, and I liked, um, uh, the creative process. I liked having my name in the byline. I did not think that I would wind up—the last thing I would’ve thought I’d wind up doing, um, uh, was becoming a professional homosexual and writing about gay people.

SO: And when did that start?

EM: That started my second semester of graduate school at Columbia, and I was writing about AIDS. That’s when it started.

SO: How did that come—how did you decide to start doing that? If, it sounds like you didn’t want that to be your niche. It seems like a strong choice.

EM: It—yeah. Do you know, I was most interested in writing about urban issues and architecture, but, um, um, there—I learned about this nun who ran a, a unit at St.Vincent’s Hospital, who was, and they were counseling gay men whose partners had died from AIDS. So I wrote about the nuns. And it was fascinating and interesting, and nobody else was writing about it.

With the headline, “Nun Leads Group for Persons Bereft by AIDS.”

SO: That is central casting nun. Sister Patrice Murphy—yes.

EM: Yeah. Yeah. And then I wrote an article, another article, which I have in this same file, with the headline, “Nobody Knows How Many Have AIDS.” That was after the nun story.

SO: Also, “Nobody Knows How Many Have AIDS” is the headline and lede of the story.

EM: Yeah. Yeah. And, um, when I reread that recently, I hadn’t—actually, I didn’t know I wrote a second article. I’d forgotten completely. In going through my clip file, I found this article, which I’d written at the end of my year at Columbia. But I wanted to know, I guess, for myself. Um, I got to ask lots of questions about how many people had AIDS. And the scary thing was, nobody knew. In reading this article, I’d forgotten how much I didn’t know about the AIDS crisis in 1984. I only learned about ARC again—AIDS-Related Complex—in reading my own article from—this would have been the spring of ’84.

———

EM Narration: Reading that article 37 years after I wrote it, a few things jumped out at me. First, I could see that in my choice of subject I was searching for answers—for myself. I hardly knew anything at the time about where the epidemic was going or whether Barry and I might be in danger. Facts were few and far between. I couldn’t even find out how many people had AIDS. There wasn’t a test yet, so it was all about symptoms. The person I interviewed at the Centers for Disease Control said about 3,000 people had been diagnosed. But the guy I spoke to who ran the Gay Men’s Health Crisis said that was the tip of the iceberg—that he believed as many as 20 or 30,000 people had AIDS-related symptoms.

“AIDS-related symptoms.” We’d gone from “gay cancer” to GRID to AIDS. Even once they’d settled on a name for the disease, defining the disease, diagnosing it, was a moving target. By this time, groups of scientists in the U.S. and France had isolated the virus believed to cause AIDS, but they weren’t yet certain. In 1984, the CDC didn’t classify you as having AIDS until you had one or more specific opportunistic infections, like Kaposi’s sarcoma or pneumocystis pneumonia. So you had to be really sick before you were considered to have what was called “full-blown AIDS.”

Then there were the people who had symptoms that were likely related to AIDS, from persistently swollen glands, fevers, and night sweats, to a mouth fungus called thrush. People with these non-life-threatening symptoms were said to have AIDS-Related Complex or ARC. It wasn’t yet clear that almost all the people who had ARC would go on to get full-blown AIDS and die.

At the end of my article, I quote the head of GMHC who says that the fact that many people may have a mild form of AIDS could be reassuring. He said, “Maybe AIDS isn’t as horrible as we think; maybe the disease varies in the degree of severity.” If only.

For virtually everyone who had symptoms in those days, there was no such thing as a mild form of AIDS. Almost everyone who was infected got really sick and died. But we were still living in the land of “maybe.” We didn’t know. And as my reporting showed me, there was no way of knowing then. The wait for answers would be deadly for many.

My tentative steps in journalism school toward connecting my identity with my work stopped abruptly. About a month before I graduated from Columbia I landed a job. Not in journalism. And nothing to do with AIDS. I went to work for a politician—the borough president of Queens—as an assistant press secretary and speechwriter. I went back to the neighborhood where I grew up, and went back into the closet. There was no way I could have gotten that job if I’d been out. Not in Queens. Not in 1984.

My life was about to become a split screen. The closeted person focused on my career. The person living out a fantasy of domestic bliss with Barry on the Upper East Side. And then there was the person who felt drawn to do something in response to the growing epidemic facing my community. Next time.

Postscript. It was heartbreaking rewatching that clip from Vito Russo’s show, Our Time. The internal conflict over how to love and make love in a time of disease and terrifying uncertainty. A community divided over how to respond, but in the end, facing the same devastating odds.

Vito Russo died in November 1990.

Charles Jurrist died in June 1991.

And Michael Callen died in December 1993.

All from complications of AIDS.

———

Many thanks to our hard-working crew at Making Gay History, including story editor Sara Burningham, assistant producer and sound designer Rae Kantrowitz, deputy director Inge De Taeye, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. This season was recorded at CDM Sound Studios. Special thanks to interviewer-slash-oral historian Shane O’Neill and our listening circle, including Syd Baloue, Cheryl Furjanic, Dr. Jamila Humphrie, Ann Northrop, Benjamin Riskin, Jenna Weiss-Berman, and Mike Winerip.

Thanks also to Hal Moskowitz and Stuart Schear for sharing their memories. And we’re extremely grateful to Richard Dworkin for the GMHC circus night footage. We’ll link to his YouTube channel in our episode notes.

Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers, with additional scoring by Rae Kantrowitz.

This season of the podcast was made possible by the generous support of the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, the Calamus Foundation, the Kipper Family Foundation, Andra and Irwin Press, Bill Kux, Jeff Soref, Kevin Williams, Kathy Danser, Hal Brody and Don Smith, and scores of other individual supporters. Thank you so much.

“Coming of Age During the AIDS Crisis” is a production of Making Gay History, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

I’m Eric Marcus. So long, until next time.

###