Feminist Bookstores: A Love Story — with June Thomas

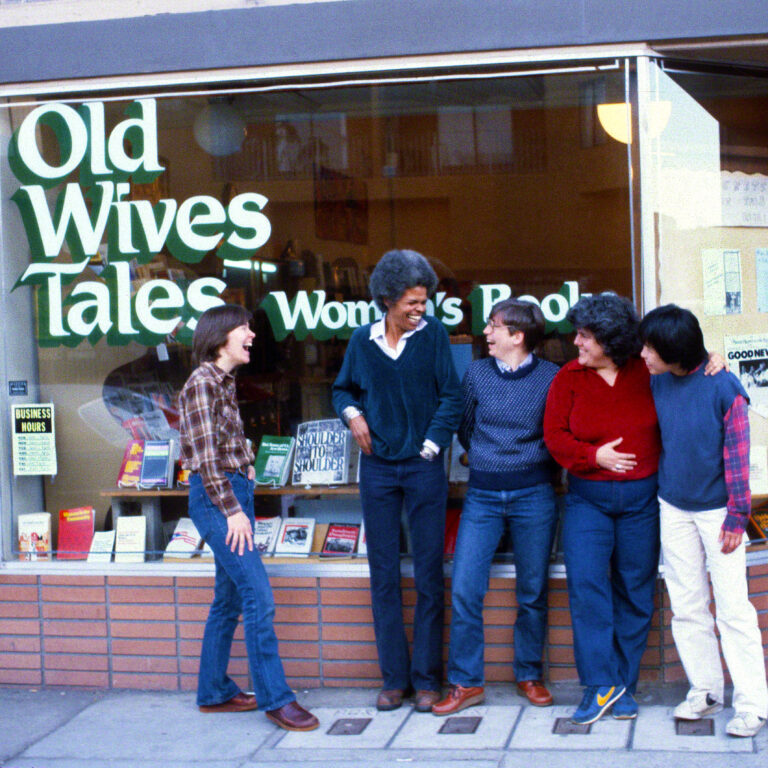

The Old Wives’ Tales Collective, San Francisco, 1982: Carol Seajay, Pell, Sherry Thomas, Tiana Arruda, and Kit Quan. © 1982 JEB (Joan E. Biren).

The Old Wives’ Tales Collective, San Francisco, 1982: Carol Seajay, Pell, Sherry Thomas, Tiana Arruda, and Kit Quan. © 1982 JEB (Joan E. Biren).

Episode Notes

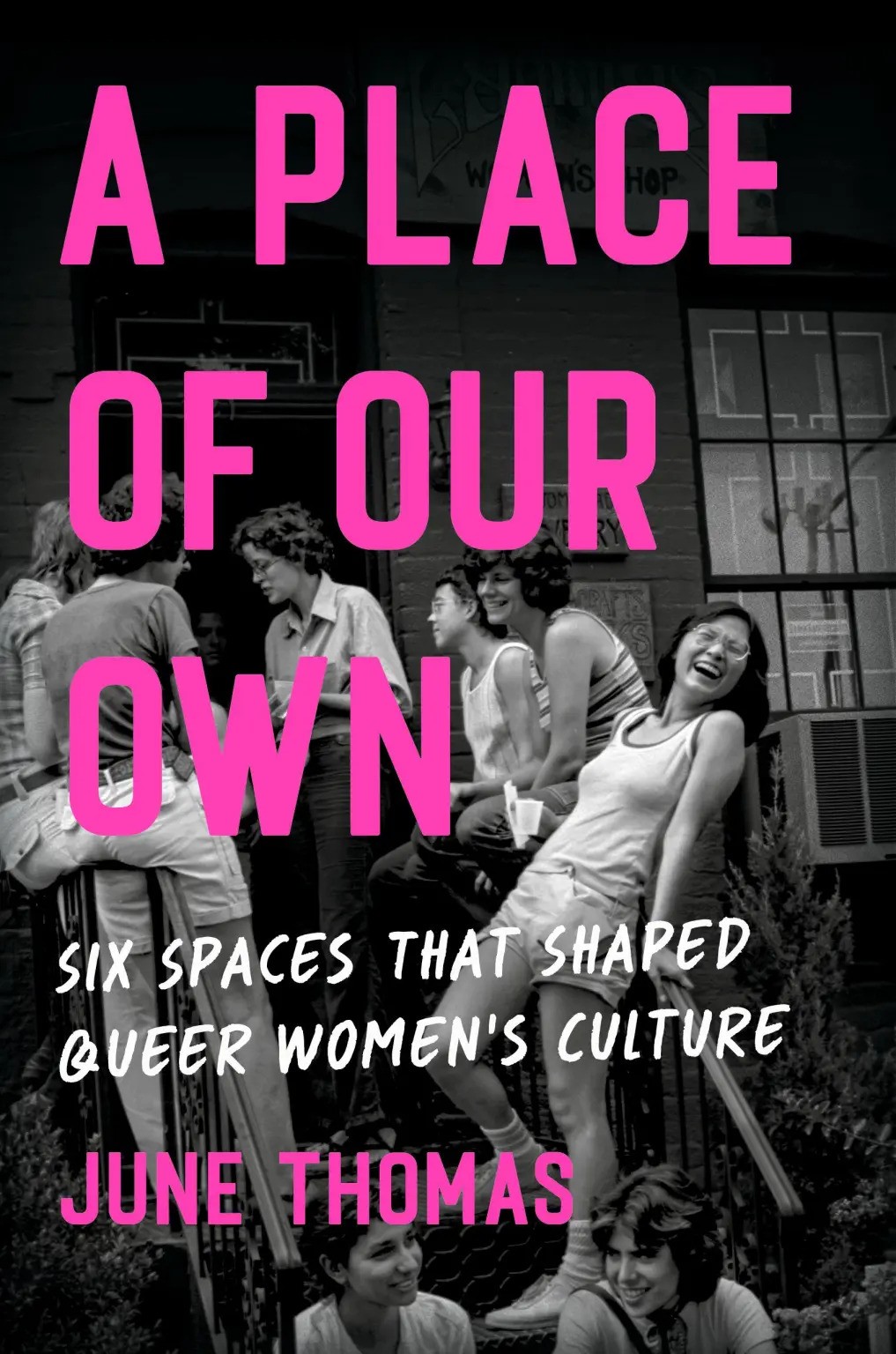

As a bookish lesbian growing up in working-class England, June Thomas developed an early love of bookstores. After moving to the U.S. in the 1980s, she found community in the feminist bookstores of the era, as she recounts in A Place of Our Own: Six Spaces That Shaped Queer Women’s Culture, which is available for purchase here.

Episode first published May 23, 2024.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus—and this is Making Gay History.

In November 2016, when we were just four episodes into the first season of Making Gay History, we got the kind of attention you just can’t buy. The Culture Gabfest—the popular, long-running Slate magazine podcast—devoted an entire segment to our fledgling pod, and it was a rave.

Leading the Making Gay History lovefest was June Thomas, the founding editor of Slate’s LGBTQ section Outward, and one of the most recognizable, beloved, and trusted voices of the Slate podcast network. She just got us, and I was thrilled when June agreed to join the Making Gay History advisory board soon after.

But it’s not June’s appreciation for our work that I want to share in this bonus episode, but rather my admiration for hers. June is the author of an important new book called A Place of Our Own, a cultural history of the spaces where queer women found themselves and their communities in the second half of the twentieth century—archetypal lesbian places where their tastes, traditions, and values were centered and supported, respected and celebrated.

It’s a deeply and thoughtfully researched account, wonderfully written, and made all the more engaging thanks to June’s wit and the glimpses she provides into her own life. Because these queer spaces mattered to June—especially the feminist bookstores of the pre-Internet 1980s. As she writes, “Feminist bookstores were my Google, my Craigslist, my Tinder—and, of course, my Amazon.”

June grew up in a former mining village near Manchester, England, in the 1960s and ’70s. After college, she moved to the United States to attend graduate school and became a journalist. She worked at Slate magazine as a writer/editor and podcaster for 25 years, until 2022, when she left her job as senior managing producer of Slate podcasts and relocated to Scotland with her partner of 27 years.

June joined me recently from Scotland for a conversation about her new book, bookstores, and embracing change.

———

Eric Marcus: Interview with June Thomas, Wednesday, May 1, 2024. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Locations are CDM Sound Studios on 44th Street and Ninth Avenue in New York City and Edinburgh, Scotland.

June Thomas, thank you for joining me today.

June Thomas: Oh my goodness, thank you so much for having me, Eric. I am very excited to chat with you.

EM: It’s a delight. And I, and I bring you here, bring you here—at least electronically—because you have a new book, uh, about to be published called A Place of Our Own: Six Spaces That Shaped Queer Women’s Culture. It’s a really important book in terms of chronicling history, but it’s also a fun read. And it’s a fun read because you’re in it.

JT: Aww.

EM: Um, so before we talk about the book and how you came to choose the six spaces, um, I wanna go back in time to when you were very young. I wonder when you realized you were different.

JT: Well, I was very different in several ways. I was, you know, I grew up in a, in a working-class home. It wasn’t an intellectual home. Um, you know, my parents had left school when they were 14. Uh, they, they had blue-collar jobs. Um, but my mom and my grandma especially, they were, they were very smart. If they’d had opportunities, you know—it wasn’t ’cause they weren’t smart that they were in the jobs that they were.

Um, and I was more intellectually oriented, so I always knew I was gonna be different. I went to very different schools than they got to go to. I had more opportunities because of that. But I also knew that I was lesbian quite early, and so, yeah, I guess when I was, uh, in my teen years, I was—actually before—in my pre-teen years, I knew, um, yeah, I, I was gonna have a different life from most of the people who I was growing up with.

EM: Do you remember an early crush?

JT: Oh, I do, but I’m not gonna say more because, uh, I don’t believe that any of my early crushes turned out to be queer. And I, and I, it’s funny, I do feel a little bit of a, an, an anxiety about making them feel bad even all these decades later. That’s really something to discuss with a therapist, I guess: why, why I think that would be something bad, um…

EM: Oh, but, but, but when we grew up, it was something bad.

JT: Yes. Yeah, yeah, yeah. No, it was scary.

EM: So we are, we’re a little hypersensitive to the, to the idea of, of labeling anybody.

JT: Yeah, absolutely.

EM: So what was the—without naming names, what was the feeling like?

JT: I was sort of prone to obsession, really. Like I, I, I envis—you know, I was, I was very imaginative, I suppose, and I, you know, would see myself, um—you know, it wasn’t sexual, I think it was before that, really—it was seeing a, a life together. It was very, um, you know, aspirational, I suppose. Romantic, very romantic, I suppose, too. Um, but yeah, very, very Sir Walter Raleigh—I don’t know why that comes to mind, but, you know, I was very, very much, um, you know, the gallant gentleman with these ladies, you know, sort of this like—it’s not how it worked out. That’s, that was not how I lived my life. But in my youth, it was very, uh, that was very much the mode that I was in.

EM: When you set out to meet other lesbians, how did you find them?

JT: You know, it’s funny ’cause I think it was very, uh, intuitive. So, even before—you know, I couldn’t wait to go to university. So even before I went to university, actually, now I think of it, there was another place that I went to find lesbians, and that was at, uh, women’s tennis tournaments. I just had a feeling that there would be lesbians there, and there were. There were also gay men—actually, I, I actually spent more time with gay men.

Um, and I really, the, the sort of, the wrangling that I was able to do, the, the, you know, the logistical maneuvering that, that I did to be able to get to these tournaments—’cause they were down, I was from the north of England and they were all in the south—um, it, you know, it really was like I was getting in touch with superpowers that I was able to, to go do this. But I did.

And, and it wasn’t about, you know, getting off with people. It was more just finding people that you could just have certain conversations with. That you could tell them things about yourself. That it was just, um—you could, it was just like a next level of, of sharing things about yourself, um, that felt just so important.

EM: And what were the women like who you met? How did they greet you? Because you were a kid—you were, what, 16, 17 years old?

JT: Yeah, they were very welcoming. And I also—I think it did help that I really did know a lot about women’s tennis. And something that was a wonderful thing was that it wasn’t only that we had queerness in common. We were also people who were, you know, subscribing to obscure publications so that we could find out what had happened in Mahwah, you know, one week in September. Uh, we knew every Virginia Slims tournament of the year. And, you know, we, we were, um, you know, we, we were just nerds. And so it was a matter of finding your people in more ways than one.

EM: A little later on, after college, um, you attended graduate school here in the U.S.

JT: I did.

EM: And you became quite deliberate in finding places. How did you do that?

JT: Again, I think it was intuitive. I mean, I was at the University of Delaware—that was 1982-83—and there was a, you know, a gay student union. Uh, and, yeah, I just, I just needed to be there in, you know, what were often quite boring, logistical meetings, but they seemed absolutely fascinating at the time because I got to be with my people.

But also, you know, I was then able to go to bars. And bookstores were very important to me—that enduring interest—um, and by this time there were feminist bookstores. Uh, we were close to Philadelphia, where there was a gay bookstore, Giovanni’s Room.

And so, you know, that was always a little bit my entree into this world—even though, like, it’s a store. It’s, you know, I could see, imagine people who didn’t have this experience think, what do you mean you found your community in a store? But you really could. You know, it, that, they were set up in many ways as community centers.

EM: You write in the book about a book that you bought that was a guide to queer spaces.

JT: Yeah.

EM: Um, it was hundreds of pages of places all across the U.S. And what did you find in that guide?

JT: Again, it was something I was really drawn to purchase, even though I wasn’t—when I bought it, I wasn’t living in America. I was very interested in America, I was very drawn to America, I did American studies at university. And so I just knew there was more, you know? It was, like, the size of America. There’s more of everything. And that meant there was more gay stuff.

And what you could find about Britain at the time, you kind of had to go, you had to call people, you had to find ads and call people to find lists even of, of pubs that were welcoming of gay people. Um, but you could buy these books about America, and they were so full of things, you know, and the craziest, strangest things that I really didn’t understand. Leather uniform bars, what was that? And, you know, cruising areas, and these things that, like, just seemed so exotic and so strange.

EM: But it was mostly places for men?

JT: Oh, absolutely. It was almost all men, but every, you know, and certainly in the big cities, there were always some “Ws,” and that meant women, mostly lesbians.

And, you know, just knowing they were there—that, it really did make a huge difference. There was a feeling, you know, when I was growing up, that I would be alone. That wasn’t actually an irrational feeling. It wasn’t like some weird, um, paranoia on my part. I think a lot of that was the story that you were told: oh, I’m sorry, you’ll be lonely. Um, you’ll have a hard life. And I never really believed that, but you, I did know that I would have to go out there and find that community.

It wasn’t gonna come to me. It wasn’t gonna be in my village. It wasn’t gonna be with my friends. I was gonna have a separate, uh, social life. Didn’t mean I was gonna not have another one. I was still gonna have straight friends. I was still gonna be, you know, involved in my family. But I also was gonna have another separate social life with, um, with, with queer people—Ws, mostly lesbians.

EM: So how did you decide to write a book about queer spaces for women?

JT: I think part of it probably was a reaction to this narrative that, uh, has kind of started to predominate of the sort of disappearance of lesbian institutions, the, the disappearance of lesbian bars, because… You know, not to deny that, yes, there are undisputably fewer lesbian bars than there were. I think in 1987 there were more than 200. Now there are, you know, I think the last official count is 32 in the U.S. So clearly, yeah, there are fewer lesbian bars.

But it also seemed to me there are so many more places that queer people can go, that queer women can go. Um, so I just kind of wanted to push back on that narrative. But also it struck me that, you know, bars are the ones that we always talk about, but they’re not the only place we get together. Um, and I also knew from, you know, from reading history that so many people over the years had tried to create alternatives to the bars.

Um, and so I just wanted to talk about some of those alternatives—places that had been important to me and places that, you know, weren’t necessarily ones that I’d hung out at, but that I knew were really important to a lot of people.

EM: What are the six you settled on?

JT: So the six I settled on were the lesbian bar, the feminist bookstore, the softball diamond—which I should say is, is kind of a stand-in for the sports, uh, field generally. Um, lesbian land, which were kind of rural retreats—rural retreats, that’s a little bit of a difficult thing to say—retreats in the countryside that, um, lesbians created starting in the 1970s, when they just had had it with mainstream society and the patriarchy, and they decided they were gonna go out to the country and they were gonna create an alternative society, basically. Um, and they did that for decades. Um, toy stores, that is to say, feminist sex toy stores. Uh, and finally, vacation destinations, queer vacation destinations.

EM: From reading the book, my takeaway was that for you personally, um—I hope it doesn’t disappoint listeners that, that sex toy stores were not the top of your list, uh, although I really, I found that section to be very illuminating…

JT: Oh my goodness, yes.

EM: Um, bookstores were, and I loved bookstores, too, so that also resonated for me. What was your first—I mean, I know, I know most of the, the bookstores were really feminist bookstores, um, that had lesbian content and lesbians in them.

JT: Yes.

EM: What was your first?

JT: The one that I think of as my first, and that was the most important to me, was Lammas, uh, in Washington, D.C. It started on Capitol Hill, right across from Eastern Market, and then they opened a second store in Dupont Circle. Uh, and I actually worked, uh, at Lammas. I worked in the Dupont Circle store mostly.

And, you know, it’s funny when I think of, of, like, how much it meant to me—certainly the, both were really quite small spaces, uh, and, you know, not terribly glamorous. They did have a lot of books. They, I mean, the thing about these stores, they really went out of their way to get hard-to-find books because they, they really had a mission. They had a mission to get ideas and songs and magazines into women’s hands. And they took that mission very seriously. They scoured the world, you know, to find the books that might make a difference in people’s lives.

And that was what they were really all about. Um, they, they were commercial projects, but what they were really, really devoted to was, um, you know, getting the word out, being there for people in the community, and providing the resources that they needed, answering the questions they had, because where else were you gonna do that?

Um, you know, there, there wasn’t a place that you could go that you knew about other than this bookstore. Because you could go there in the day, and it wasn’t as scary as it was to go to a bar. And they were in the center of town. There were no age restrictions. You know, it’s a bookstore for goodness’ sake.

EM: How did you come to decide to work at a bookstore?

JT: I mean, you got a discount. What a better place? It, it, it didn’t, almost didn’t matter how much it paid. You got a discount on books and on all the other things they sold. How else was I gonna keep having—you know, I needed seven T-shirts with things written on them that absolutely identified me as a lesbian feminist. I, I needed a discount to get that many T-shirts in my rotation. So, yeah, I was gonna work at Lammas.

EM: What were the, the people like who came in and, and what kinds of questions did they have for you?

JT: I remember just being wowed that people would come in, especially on the weekends, you know, they would come in on Friday—they probably were coming from work—and they would buy what felt like dozens of books. It was probably, you know, four or five. And they would often buy, you know, what were then the Naiad, uh, romance novels. Um, and, you know, I, I would be, I was a, you know, I was an intellectual, you know, so I was a bit sniffy about those books.

And you know what? Those books kept those bookstores in business and, you know, all power to them because, uh, now, you know, with the, the sort of benefit of age and wisdom, I realize women were looking for, you know, a happy ending. They weren’t necessarily seeing it in their lives, but they wanted to see, you know, women get together and have happy lives. And, you know, why, why, why would I be sniffy about that?

Um, there were lots of people who would be coming in to buy tickets for women’s music concerts. You know, uh, feminist bookstores were very much part of that ecosystem. Um, you know, the, they, the, so the stores sold those albums and tapes, uh, as they were then. So there was a big section that had to really, you know, have strong underpinning because albums were so heavy and tapes were such an awkward size. Um, so you would be playing those songs, people would like—and you, and you got people coming into the store who you could tell were really discovering something about themselves.

And, you know, the, the, even though these stores were small, they had these binders, these, you know, three-ring binders full of resources, full of flyers from, you know, 12-step groups and, and birding societies, and affinity groups for political actions, all different kinds of things. Um, but you knew that you could find out about all kinds of different areas of life in a bookstore.

EM: One of the things you write about is how difficult it was for these stores to get off the ground because of laws that made it difficult for women in particular. And so what was the, the financial world in which the women who founded these stores found themselves?

JT: Yeah, so, I mean, the easiest thing to point to is to say that women, you know, had no right to get a credit card until a piece of legislation was passed in 1974. But of course it wasn’t only about credit cards. It was, mortgages and just getting access to credit, which you needed to—and still need—to start a business. And so there were, you know, some movements to create new ways of starting businesses, feminist businesses, especially. There were these new feminist credit unions. Many women who came out as lesbians had been married, and they sometimes had access to credit because of their husbands or their soon-to-be ex-husbands.

But, yeah, it was just extremely difficult. Um, and even allowing for inflation, the amount of money that people started stores with was, you know, tiny. They, they really, they often weren’t paying themselves, basically. Um, and they, you know, they were just keeping it going on motivation and, and ideology, and, uh, I’m very conscious that so much of what, of the institutions that I write about, they were made possible by people who really sacrificed.

Um, and they’re not—you know, I’m, I hear myself talking about them in the past tense. They’re not gone. There are still several bookstores that were launched in the 1970s that are still open today. You know, Charis Books & More in Atlanta, Women & Children First in Chicago, A Room of One’s Own in Madison, Wisconsin. They’ve all been open for more than 45 years. They are still doing great business.

A whole bunch of new feminist bookstores, uh, and queer bookstores have opened in recent years. They are not exactly the same as the bookstores were in the ’70s. In many ways, they’re more inclusive. What they’re selling is different because what people need is different. But that sense of, you know, allowing women to find the ideas that they need to find—that is still hugely important.

And of course the feminist bookstores that closed—just because places close, it doesn’t mean they fail. They had huge impact. They changed women’s lives. They changed the business, they changed publishing. Their closure doesn’t mean failure. And I, I really want us to push back on that.

EM: Looking back now, how important were all of these places that you write about for finding identity…

JT: Yeah.

EM: … and building community?

JT: One of the things that is really important, and that I think I only really understood when I was just kind of researching and writing about 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 places: the thing is that they all interact. And it, you know, it’s more than just these six places, but if you find a community, it’s like you—to use a very strange perhaps picture—like, you hold one hand and then you meet another person, and then you’re kind of holding all the other people’s hands that they’re connected with.

And one of the cases that I came across was what became known as the Shescape 7, even though there were nine of them—I think that’s lesbian math. But, um, the, Shescape 7 were a group of women who filed a complaint with New York City’s Commission on Human Rights because they noticed that Shescape—which first was a bar, uh, and which later when the bar closed, ran kind of party nights at other venues across the city—they perceived a pattern of discrimination being used when it came to who was allowed into bars and club nights.

And one of the women who I spoke with, who had been part of the Shescape 7, was Jacqueline Woodson, who is now a very famous writer. And she didn’t want to be an activist in that sense, but when a group of women were kind of, you know, in the dugout, uh, in Brooklyn at the Prospect Park Women’s Softball League, they were talking about where they’d been and where they’d gone, and they realized that, hmm, that bars weren’t letting in Black women, especially when they were in groups of Black women. If they were in a group with several white women, there was a larger or higher chance that they would be allowed in.

And it was, it was more of a pattern of, of realizing a pattern, and also just getting worked up about it. Um, and they then went to the Brooklyn Women’s Martial Arts, uh, group that met in Park Slope, where many of them trained. And they, you know, did some organizing there. And just, the reason I’m mentioning this, it’s just this path of bars to softball to martial arts gym…

Uh, they then founded a group called COOL, which was Coalition of Outraged Lesbians. Um, and, you know, even though there was a settlement, I can’t claim that they got the response that they deserve, but it was just really heartening to see just a very concrete example of how you start with, something happens in one place and then it moves kind of throughout these other spaces in the community.

EM: So while you write about six spaces, the spaces were interconnected.

JT: Absolutely, absolutely. There were lots of interconnections that when you went into one, you actually found out about a whole lot of other places that you could go and a whole lot of other activities that you could get involved with.

EM: One of the things I’ve, I find I hear among people my age and older is how much they resent change, how much, how different things are.

JT: I mean, it’s definitely different now, and I, I never wanna be that person who’s like, “Oh my god, in my day, it was so great. Now, I don’t know,” you know? ’Cause, no, it, it…

EM: Oh, it’s so tempting to say that, June.

JT: It is tempting to say that, but no. Yes, there were so many more lesbian bars in 1987. Would I step back into 1987? Not for a second, and show me anybody who would, and I need to have a really serious conversation with them. No. The world is so much better and more friendly. And we have so many more rights and so many more places we can go, and so much more that we can share publicly. So much more that we can do publicly.

And every time I hear myself, like, oh, things… Even thinking things were so much better, or… Of course you can wish, you know, for, for places where you were happy, for those to, for other people to be able to visit those. Like, it was amazing to go into Lammas on a Saturday afternoon. Um, it was great to be at Tracks, uh, you know, on, on the last Tuesday of the month, which was women’s night, uh, in Washington D.C., in the 1980s.

But it’s okay that they’re not there anymore. And every time I hear myself, like, “Oh, kids today,” I mean, really, that is, you know—the next step is, you know, shaking your fist at clouds and yelling at people to get off the lawn. Never let me say that, please.

———

EM Narration: June Thomas continues to co-host Working, Slate’s podcast about the creative process.

You can find her book—or, let me take a crack at that in June’s gorgeous accent, “bewk”—wherever books are sold. It’s called A Place of Our Own: Six Spaces That Shaped Queer Women’s Culture and it’s published by Seal Press.

———

This bonus episode was produced by Inge De Taeye with help from studio engineers Katherine Cook and Cathleen Conte. A transcript of the episode is available on our website at makinggayhistory.org. That’s also where you can find all our previous episodes along with resources and archival photos.

If you’d like to hear from us between seasons, please consider becoming a member of our Patreon community. It’s just $5 a month and supports our mission to bring LGBTQ history to life through the voices of the people who lived it. Find out more at patreon.com/makinggayhistory.

Making Gay History is made possible thanks to the ongoing support of the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, the Calamus Foundation, and Christopher Street Financial.

We’re deeply grateful to the many people who provide generous funding to support our work, including Eric Lee, Ty Ashford and Nicholas Jitkoff, Mary Cadigan and Lee Wilson, Hal Brody and Don Smith, and David Quirolo. Thanks, David.

I’m Eric Marcus. So long, until next time.

###