Stonewall 55: Myth & Meaning

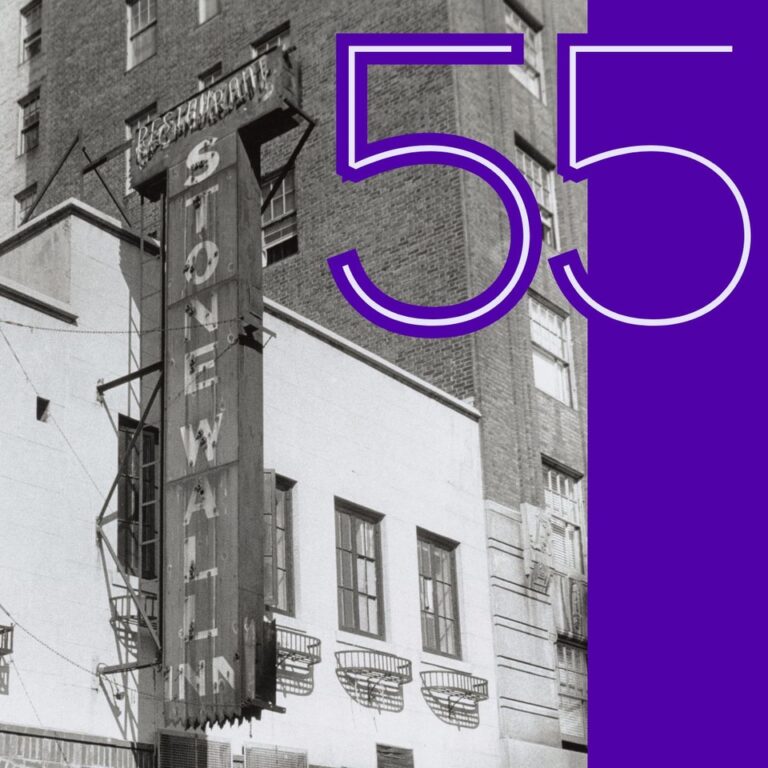

The Stonewall Inn, September 9, 1969. Credit: Photo by Diana Davies, courtesy of

Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

The Stonewall Inn, September 9, 1969. Credit: Photo by Diana Davies, courtesy of

Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.Episode Notes

Can historical and emotional truth coexist? For the 55th anniversary of the uprising, Eric and fellow LGBTQ history expert Ken Lustbader talk to Stonewall National Monument visitors and let a few myths slip by to uncover Stonewall’s moving resonance as a symbol of LGBTQ liberation and joy.

This episode is a co-production of Making Gay History and the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, in partnership with the National Park Service. It was first published on June 14, 2024.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus: Hello, may I talk to you for just a second?

Spanish Tourist: Uh, I speak English so-so.

Eric: Okay. Un poquito. Do you know what this area is, uh, what this park is?

Spanish Tourist: Uh, uh, I think it’s the park [speaks Spanish].

Eric: In English maybe?

Spanish Tourist: L, um, LBTG…

———

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

When it comes to Stonewall, I’m a broken record. For the past 35 years, I’ve tried to separate fact from fiction about what happened at the Stonewall Inn back in June 1969 and how that landmark uprising against police repression fits into the broader history of the LGBTQ civil rights movement. First in my Making Gay History book. Later in newspaper columns and interviews. And then in 2019 in this podcast, when we produced a documentary series about the Stonewall rebellion to mark its 50th anniversary.

Mostly it seems like I’ve been spitting in the wind. That’s because the myths around Stonewall seem to have only grown more entrenched: that the Stonewall uprising was the beginning of the gay rights movement; that it was trans icon Marsha P. Johnson who threw the first brick that started the rioting; that it was grief over the recent death of Judy Garland that fanned the flames of the bar patrons’ anger… And that’s just a few of them.

Of course, accounts of what happened back then were always going to differ. Riots are messy, memories are fallible, and recollections are biased. And given how consequential the Stonewall uprising was to our movement, this is high stakes history: to have been there, to be acknowledged as having been there—it matters.

In fact, that’s how we at Making Gay History ended up perpetuating a myth about who was there ourselves. In our Stonewall season, we included trans activist Sylvia Rivera’s eyewitness account of the first night of the uprising. That account has since been disputed by independent sources who said Sylvia wasn’t actually there. But after years of oppression, of sacrifice to advance the cause, and of marginalization within the movement itself, it’s easy to see why Sylvia might have felt she had earned the right to claim some of that Stonewall history as her own.

And Sylvia’s account, as she told it to me in 1989, still packs a punch. That’s often the thing about myths: they inspire, and they have force.

That was brought home to me and my friend Ken Lustbader on a recent early summer day when we visited the Stonewall National Monument in Christopher Park, across the street from the building that once housed the original Stonewall Inn.

Ken is the co-founder of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, an organization that documents queer spaces in New York City from the 17th century to the year 2000. He was also one of the key players in the yearslong campaign to get the Stonewall National Monument designated by President Obama in 2016.

With the 55th anniversary of the uprising on the horizon, Ken and I decided to ask visitors why they’d come to Christopher Park, what they knew about Stonewall, and what it meant to them. We talked to people from near and far, queer and non-queer, young and not-so-young. Some were well-informed, others not, and still others had been weaned on a diet of Stonewall myth. But what we heard about the emotional and symbolic resonance of Stonewall that day was almost enough to make us not care about that.

———

Will Coley: Oh my god, it’s so freaking noisy here.

Eric: It’s so noisy.

Will: They’re doing hammering there… I don’t know what…

High Schooler 1: Hello!

Eric: Hello! Why did you come to the Stonewall National Monument?

High Schooler 2: Uh, we’re on a school trip from Metuchen, New Jersey, uh, with the GSA, which is the Gay-Straight Alliance.

High Schooler 1: We find that it’s very important to not just, like, in a classroom learn about queer history, but also go out and experience it. And New York and also in particular, uh, Stonewall, it’s, you know, very important to learn about these things. And so we try to come out here every year, and the first year that I came here, I remember standing in front of Stonewall and just feeling like, you know, I’m standing where people were standing when such monumental queer history was made, and there isn’t a feeling like it, you know.

High Schooler 3: It’s really magic. Um, I’ve, I’ve done a lot of projects on Stonewall across the years, since, like, eighth grade—so, like, five years. Um, and it’s, it’s really, really cool to sort of see where it all happened and sort of feel it out for yourself.

Ken Lustbader: What drove your interest in this particular subject matter, uh, at such a young age and continuing through now?

High Schooler 3: Um, I mean, part of it was being queer. Like, I’ve, I’ve had a sense for that since fifth grade, but once I started delving into queer history, there’s something really… Like, I was born 2005, right? So by the time that gay marriage was legalized, I was 10 years old. I had no idea, like, what that meant, you know? I was kind of just like, oh, everyone’s really excited for this. Um, but then to learn about, like, where all of that came from and to just get a sense of what queer history really is and, like, what Pride really is. The fact that, like, the greatest form of protest was to be proud of who you were and was to have joy, you know?

And I don’t think anything has taught me such exuberant joy as being queer has and as learning about that has. So it really kind of feeds into itself and it’s this whole beautiful amalgamation of, like, why we’re here today.

High Schooler 2: For me, as a trans person, uh, Stonewall means a lot. It, like, tells me that we have had trans people who came before us, which means, you know, like, we’ve always been people who have been living and are alive. And it just makes me feel better about our movement now. And it, like, validates my story as a trans person and lets me know that there are, have always been people fighting.

High Schooler 1: I think it also, to me, uh, means a lot of stuff about, like, how we interact sort of with, like, police and our police department, and, like, how… You know, it, it’s very topical today even. Uh, you know, we’re doing better on the queer front, but, you know, police brutality and inequality is still something that’s very potent. And I think there is still something to be learned from the way that we handled things, uh, at Stonewall for how maybe we should be handling things today, even outside of queer sectors.

Apollo: My name is Anne Leghorn or Apollo, and I’m a teacher in Metuchen schools. I lived in the city for quite a long time and went here when I was a young person, like, coming into my own identity as a queer and nonbinary person. And so, for me, it’s important to recognize that it’s not just a place for people to go and have fun, but it’s really the beginning of a movement that’s changed, like, who we are and how we can be in society.

Eric: And how did you decide what to wear today? Because I noticed you have a few accoutrements related to the LGBTQ civil rights movement.

Apollo: Um, we kind of consider this our, like, kickoff to what we do for Pride month in school. And so I just wore everything that symbolizes to me everything I wanna wear during Pride month. So I’m wearing my T-shirt that says “Nonbinary.” I’m wearing a black shirt that has rainbows printed all over it. I have our school’s, uh, Progress Pride flag that we hang every year. Um, and a rainbow backpack that I use all the time. Oh, and of course my trans ribbon and my “Pronoun: they/them” pin that I wear pretty much every day.

Eric: That’s great.

Apollo: Yeah.

Dina: My name is Dina.

Janine: My name is Janine.

Eric: And where are you visiting from?

Dina: From Germany. All of us.

Janine: Nuremberg.

Eric: From…?

Janine: Nuremberg.

Dina: Bavaria.

Eric: Ah, from Bavaria.

Dina: Do you know Bavaria?

Eric: Yes, I know it on a map.

Dina: Okay.

Eric: Yes. So, uh, question for you is, why did you come to the Stonewall National Monument?

Dina: It’s the first time I have heard about it. Um, my, my friend, uh, just told me a few seconds or minutes ago that there was a first, um… Wann war die…?

Janine: [Says 1969 in German.]

Dina: There was a first, um, um, um, kind of, um… Was war da?

Janine: Schwulenbewegung. Gay, uh…

Dina: Um, I don’t know, uh, the right word in English, um…

Will: Protest?

Dina: The end… Pro—yes, protest. Thank you. Um, at the end of the, the ’60s, ’70s. Yeah.

Ken: Are you aware of any other monuments, say, in, in Germany for homosexuality or gay rights?

Dina: I don’t think so.

Janine: Köln.

Dina: Of course, Christopher Street Day, we have read it. Um, it’s, um, a protest, a kind of protest in Germany as well. I think…

Janine: Köln. Cologne.

Dina: Cologne, one time, one time a year? Einmal im Jahr?

Janine: Ja.

Dina: So, okay, so maybe it, it could to be compared with, with, uh, Christopher Street Day in, in U.S.

Eric: Do you wanna explain that, Ken?

Ken: Sure. We, this is Christopher Street behind us.

Dina: Ah! So that… Ah, okay.

Ken: Right.

Dina: Ja, I can read it.

Ken: And the, and the bar, the Stonewall bar is over there. Those were, those two buildings there. And that’s where in 1969 the uprising took place.

Dina: Okay.

Ken: So Christopher Street became a really important, uh, thoroughfare and place for congregation for the gay community to, uh, resist police oppression and societal oppression. And that’s why it was adopted as a name in the US and throughout Europe for many of these, uh, annual celebrations of LGBTQ Pride.

Dina: So this is the base? Okay!

Ken: Yes.

Asbjorn: Uh, my name is, uh, Asbjorn Slettemark. Classic Norwegian name. Um, and I’m from Norway, but now I’m living here in, in New York, in, in Chelsea, with my wife and my son.

Eric: And what brings you to the Stonewall National Monument today?

Asbjorn: Uh, today I have some friends visiting from Norway. Uh, and we had, um, lovely espresso and some, uh, cookies at the Bar Pisellino. But then I wanted to show them the Stonewall Inn and just, like, give a little background to why Stonewall Inn is so important—not just for us who’s, like, living in New York for just a brief period of time, but also for New York and basically for, like, the history of the modern Western world, I guess.

Eric: And, and why do you feel it’s important to know the history?

Asbjorn: Uh, I think it’s important, maybe especially in these days, because… I grew up in, like, the ’90s with a probably, like, like, a positive look on the world. Like, you know, the Berlin Wall had fell, um, communism had gone away, we sort of fixed the ozone layer. And I think, like, okay, now we fix the world.

I mean, like, and everything felt, like, liberated and free. But then the world has taken a far darker turn in recent years. And I mean, like, the Stonewall Inn, uh, and the history of gay rights in America feels, like, more important than ever just because of the dark times of—it, it’s not, like, just because of those, but it’s also symbolic of the freedoms that we all are fighting for.

Ken: You brought your friends here. Did you, what was the impetus for you to bring them to the physical location rather than just telling about that history?

Asbjorn: Well, I think, I think for me it’s—we were actually just talking about that. I mean, like, you can read about things, you can watch documentaries, but it’s nothing—that is nothing compared to, like, just, like, looking at things on your own, just, like, feeling the vibe and, like, the magnitude of an historic place.

And as I, I guess, being a journalist myself, I always, like, I want to, like, get as close as possible to things and just, like, watch, like, the scenery, the geography of the place. And is it bigger than I thought? Is it smaller than I thought? Which makes history comes alive in, um, in a beautiful way.

Benjamin: So my name is Benjamin Rivers.

Eric: Uh, let’s just move into the shade just so we’re not cooking.

Ken: What does “Stonewall,” the word, mean to you?

Benjamin: Interestingly, when I think about it, I, I literally picture a stone wall, like, building that around our community. I’m a teacher, so I think of building a stone wall around my kids to protect them as they are growing and figuring out who they are, and making sure that they have a safe space to do that.

Eric: Where, where do you teach, uh, what part of the world?

Benjamin: I teach in Kansas.

Ken: So you’re really visiting New York.

Benjamin: Yes. Yeah. I really am visiting.

Ken: You’re not in Kansas anymore.

Benjamin: No, most definitely.

Ken: What’s it feel like to be here, to see the physical location?

Benjamin: I think it’s affirming. You know, I, I have a group around me in Kansas that is very warm and welcoming and loving, and we’re kind of all over the, the spectrum of gender and sexuality and, you know, identity as a whole.

Um, but it’s nice to come in a place where it’s just, queer’s the norm. And to be in a space like that, um, is rather wild when, you know, I’m watching the states around me enact these draconian policies that are incredibly terrifying. And my own state, you know, having legislatures keep trying it and they keep trying it. And luckily we’re able to hold them off, but, you know, for how long?

Emma: I’m Emma. I’m an international student, uh, studying in California and I’m from Taiwan. Um, actually it’s my first time to New York and I think—I visited the Castro Street in San Francisco and, because I live in Berkeley—and I think it’s really cool for me to visit another site that is really important to this whole, um, group community. Yeah.

Ken: What does Stonewall mean to you?

Emma: Um, I think, um, although it’s really, like, far away from my own home country experiences, but it’s still an iconic place or iconic group of people that encourages, like, um, nonbinary and other LGBTQ community in our society. Like, it’s kind of a radical symbol for us to, um, like, aspire to or be encouraged, I think.

Ken: And now that you’re here, um, what’s this feel like for you to visit this location and see it in the physical sense?

Emma: Yeah. Yeah. I think it’s really cool that, um, it’s, like, a little park and people just feel it’s really normal to be here. It’s not really, like, a particular, um, special place, but I think it’s really good to see a lot of people come from different background and maybe have different meaning about this, of this park, and sitting here and looking around. And maybe they’re not familiar with the history, but when they come into this place, I think seeing those signs and statute [sic], they may be inspired or try to, um, know more about the history. I think it’s really good to have a physical site for people to gather here.

Gale: I’m Gale Bonnell and I’m from Charlotte, North Carolina.

Eric: Thank you for talking with us.

Gale: Sure thing.

Eric: What brings you to Christopher Park and the Stonewall National Monument today?

Gale: Okay, well, I happened by, I’m on business. I had a little time before my next meeting and I needed a place to sit down, and I walked in and I thought, well, this looks great.

Ken: And did you know that you were actually sitting at the Stonewall National Monument in Christopher Park?

Gale: Uh, not until I sat down in the park itself and realized, you know, you know, what, what the intent was behind it.

Ken: Mm-hmm. And, and when you realized you were sitting at this place that was a pivotal location in civil rights, American history, did that change your sense of place or where you were?

Gale: Absolutely.

Ken: Mm-hmm.

Gale: And I, and that’s the beauty of this park, is that sitting down, I think, if more people, you know, stopped in and took a few minutes just to sort of think about it. I mean, I, the thing I love about being an American is, we need equal rights, human rights, dignity for everyone, fairness, equality, all those things, regardless of how people are defined.

Jesse: Hi, I’m Jesse Martinez, and I am, uh, currently from the Phoenix Valley. Uh, grew up in San Francisco Bay area.

Eric: And what brings you to the Stonewall National Monument today?

Jesse: Um, well, my husband’s a flight attendant. He had a great layover, so we’re here for 24 hours and we decided to come down here and check out the area. I wanted to definitely see Stonewall with Pride coming up in just a couple weeks.

Eric: So why Stonewall? Why, why is it, what does Stonewall mean to you?

Jesse: It’s actually pretty crazy because, just recently we actually had a death threat from somebody, just some guy, um, just because we’re gay, threatened to shoot us. And it made me realize how important it is, the, the history that we have as a LGBT community, and it reminds me so much of Stonewall.

I was less than 10 years old when it happened, but I think it’s, I’m excited that it happened because I grew up, got married, had kids—got married to a woman, had kids—was married for 20 years. My kids are now in their 40s. I’m 60—almost 62. And it’s great to see that everybody’s so accepting. There’s so many people that are so accepting. It’s, it’s, I think it’s more and more few and far between that they’re not. So when you see all of this going on, it’s sort of a celebration of how far we’ve come.

Eric: What do you think when you see the National Park Service and a National Park Service ranger, um, here in Christopher Park talking about Stonewall?

Jesse: I think it’s great. I, I—just like Yosemite, just like any other, you know, the Grand Canyon… I didn’t realize there was a national monument. I just learned that as we met. And it’s just incredible to see that, to see, you know… I, I’m part Mexican and you see, you know, the whole Mexican movement, the Latin mu—movement, um, uh, Black Lives Matter, all of that stuff. And it’s great to see this.

Ken: Do you think when you leave here, what’s the intangible sort of feeling you’re gonna have that this is now sort of imprinted on your mind when you go back and deal with those kind of threats?

Jesse: I just feel more accepted. I feel there’s more of a community. Um, it’s great to see that there’s something that’s national that’s being recognized for this. So I feel stronger when I stand up for myself, because in the past I wouldn’t have stood up for myself.

Um, when I was a kid in school, I didn’t stand up for myself. And now I’m learning, even though it’s still late at 60, that… I’m standing up for myself, and I’m, and I’m not just standing up for myself, I’m standing up for those in front of me and behind me.

Eric: Please introduce yourself.

Julie Burna: Oh, hello, I’m Julie Burna, lead ranger, Stonewall National Monument. I use any pronouns.

Eric: And I notice on your desk, um, that there is a stamp and an ink pad.

Julie: Mm-hmm.

Eric: What is that?

Julie: What, do you not collect the cancellation stamps? I do. I’m a huge fan. That’s how I came into the Park Service. And, um, yeah, we have all the amenities of any other, like, Yosemite, Grand Canyon, we’re all in the same tradition. So we have cancellation stamps, so each site will have, um, a stamp that you can collect. We also have the unigrids, we have junior ranger programs, we have the websites, the social media. We got it all.

Ken: Maybe you could describe what you’re wearing so…

Julie: Oh, sure. Well, I, I often call this getting into quick drag. You know, it’s a uniform, I don’t wanna be disrespectful, but, you know, there’s lots of different pieces and different—you know, I use different pronouns so, um, … But I do like to wear the little skirt. Um, I have little, um, heels on, I have tights, a very fitted blouse with my badges, and then the very sassy, you know, park ranger hat that everyone knows and loves.

Ken: No, I think the park ranger hat is the sort of iconic symbol…

Julie: It is.

Ken: … uh, with the arrowhead, too.

Julie: Yes.

Ken: So it’s, it’s pretty reassuring when you walk in…

Julie: It is.

Ken: … to this place that it is now federally recognized…

Julie: Yeah.

Ken: …with your assistance. I was involved in the advocacy efforts to get Stonewall National Monument designated, um, and I would’ve never imagined that I’d be sitting here next to a park ranger from the National Park Service, who is the official ranger for that monument, talking about LGBTQ history in the location where it was made. So it’s very affirming and moving and gratifying to me—I’m gonna…—to be here with you. So thanks.

Jim: Hi, uh, my name’s Jim. I’m from Nottingham, U.K.

Eric: Jim, what brings you to the Stonewall National Monument today?

Jim: We were just wandering. We’re on the way to Washington Park. I knew about Stonewall and I didn’t realize that inn was just there, but, uh, I thought, yeah, I know about it, let’s have a look. I’m not gay myself, but I’ve got plenty of gay friends, I’ve been on the marches with them. I thought, yeah, I cannot miss that ’cause they’ll love it.

Ken: And what do you know about the Stonewall uprising?

Jim: Not a huge amount. I know it’s important to the community, not just LBGQ plus, but also for the straight community as well. If we can’t work together, we can’t work alone. So, yeah, yeah, yeah, I’m pleased to be here.

Eric: Thank you. Thank you for coming here and talking to us.

Jim: Thank you. No problem. Nice to be in your beautiful city.

Eric and Ken: Thank you.

Ken: Have you been to New York before?

Jim: No, I haven’t. Greatest city on earth.

Ken: And so you said you were going to Washington Square Park?

Jim: Yeah, which way is it?

Ken: What is your name and where are you from?

Roy: Roy Fernandez. I was born in Cuba, but I was born at—well, eight months… Uh, living in Brooklyn, New York, all my life, and I currently live in the East Village. I vividly remember the Stonewall uprising. I was a sophomore in high school. And I guess I was about 15 and sort of getting in the trajectory of going out and meeting folk. Uh, so when that happened, it just blasted everything apart.

But for me it was affirming that for once we weren’t gonna sit back and let people walk and crawl all over us. So events like these helped me gain identity and come out and know that I wasn’t alone. It certainly encouraged me to advocate for who I am, uh, not to feel ashamed for who I am, uh, and to go out and help people, you know, with that, uh, which I did during the AIDS crisis, um…

Ken: What does it feel like for you now to know that you’re at a national monument and being in this park and connected to the physical location of Stonewall?

Roy: When this started coming up, I said, wow, it’s really just amazing that, you know, we were able to do that and that it’s in our own backyard. I mean, certainly when I saw St. Vincent’s Hospital being remodeled, uh, it was really painful because I lost two good friends in the hallway there. When physicians weren’t even going near gay men because they were afraid of how they were going to contact the, you know, immune deficiency virus.

But, um, so they did do the AIDS project across the street, the monument there, which is fine, but this is about power, you know. It’s not really about sympathy. Uh, I think the other is about sympathy, not so much power. I think it’s important, equally, but I think this has a much stronger voice, uh, than, you know, the AIDS Memorial by St. Vincent’s.

Larah: I’m Larah Helayne. I live in Bushwick now, but I’m originally from Kentucky. Uh, Stonewall means a lot to me. I come here a lot. Um, and the reason that I come here a lot is the significance of this space. It just feels so sacred to me. Uh, I feel like Stonewall is the reason that I have anything. Beyond gay marriage, beyond legal rights, beyond any of that, Stonewall is the reason that I know that queer community exists and know that queer resistance is effective, and that when we band together, we actually get what we want.

Um, yeah, I, I’ve been thinking a lot about—as a trans person, like, when I go to Stonewall, um, to my knowledge, I don’t know of any, like, trans men, names of trans men, that we have that were at Stonewall. Like, I know that we were there, it’s just a matter of, were trans men identifying as lesbians because that was the closest language that they had at the time, or were they passing as so stealth that their transness wasn’t even factored into the consideration. Um, but when we come here, I feel this duty almost to, like, be here and show up as my full self for the gay trans men that never got that, who never got to be out and got to be proud.

Um, and when I get very fed up with living in New York, all I have to do is come to the Village and I feel like I’m taking a walk with the Village ghosts. You know, like, start here, go to the [LGBT] Center, … Think about the Stonewall riots that happened here; think about all of the organizations that came out of that; think about Mattachine and ACT UP and all the different predecessors and ancestors that came before me that have walked these streets and literally paved the way for me. Um, so, yeah, I mean, it’s sacred, is really the first word that comes to mind for me when I think about Stonewall.

Will: Sorry, were you gonna say something?

Ash: Oh, I was just gonna say, yeah, every time we come here to the Stonewall, it makes my heart really happy to hear him be like, “Oh, and here’s this and this and this.” And I just love learning gay history from you, so…

Larah: Thank you.

Eric: Can you identify yourself and say where you’re from?

Ash: Yes, my name is Ash Sloas. I am also from Kentucky. Uh, I live in Bushwick with my partner Larah.

Ken: And what brought you to New York in the first place?

Ash: Honestly, trying to figure out my place in the world as a queer person and figuring that New York is the safest way to do that as a, a queer trans person, as an artist. There’s so much visual art here that really fills my well, and also so many other queer people that I don’t feel like I’m stepping out of my house to be hate-crimed anymore, which is really nice.

Ken: Mm-hmm. And how does it feel to be at the Stonewall National Monument and visit this place?

Ash: It feels like the culmination of all of my years of wishing and hoping for community. Now I’m here where a lot of the national movements just started and sparked up. And being here and, like Larah was saying, with seeing all these Village ghosts, it really reminds me that we’ve always been here. And that’s really, really helpful a lot on my dark days.

Ken: And why is it important for you to share that information about queer history and what does that mean for your generation?

Larah: I feel like queer people have an obligation to stay true to everything that our, like, ancestors fought for, and to remember that it really is about liberation at the end of the day. As much as we are able to, like, be a part of society in seemingly more seamless ways now, like, we still are fighting for liberation for so many people. And I think that’s why it matters. It matters to have a precedent.

———

Eric Narration: Does historical accuracy matter? Absolutely. But even a stickler like me can make space for a fuzzier, more emotional truth if it instills in LGBTQ people such pride, courage, and empathy. Not to mention a healthy dose of defiance and much-needed vigilance. There’s hope and strength in that.

But you won’t get me to say the facts are beside the point. In the words of preeminent Stonewall scholar, the late David Carter, “If we are demanding that our history be respected, then we have to respect it ourselves.”

So over the course of this Pride month, as we commemorate the 55th anniversary of Stonewall, I’m sharing our Stonewall season again. Because it sets the stage for everything that came after. Because it honors those who came before. And because, even without the myths, it is one hell of a story.

———

This Making Gay History episode was produced by me, Ken Lustbader, and Inge De Taeye, with help from field producer Will Coley. Our studio engineer was Elvira Gutierrez at CDM Sound Studios. Our music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Many thanks to the wonderful people who lent their voices to this episode: the GSA high schoolers from New Jersey and their advisor Apollo, Dinah and Janine, Asbjorn, Ben, Emma, Gale, Jesse, Jim, Roy, Larah and Ash, and National Park Service ranger Julie Burna. Thank you also to our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter.

A transcript of this episode is available on our website at makinggayhistory.org. That’s also where you can find all our previous episodes along with resources and archival photos.

Making Gay History is made possible thanks to the ongoing support of the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, the Calamus Foundation, the Zegar Family Foundation, and Christopher Street Financial.

We’re deeply grateful to the many people who have generously donated to support our work, including Mary Cadigan and Lee Wilson, David Quirolo, and Eric Lee. Thanks, Eric.

If you’d like to hear from us between seasons, please join our Patreon channel. That’s where you’ll find bonus content like new video chats I conduct with LGBTQ authors, film folk, and history makers. It’s just $5 a month and supports our mission to bring LGBTQ history to life through the voices of the people who lived it. Find out more at patreon.com/makinggayhistory.

I’m Eric Marcus. So long, until next time.

———

Ken: What, what do you know about the Stonewall uprising?

Benjamin: Um, well, I know, you know, our, our myths that we’ve built around it—that, you know, Marsha P. Johnson threw the first… But if there was actually a first… And all the debate that happens around, you know, um, all of that. But I know that, um, a bunch of queer people were sick and tired of being told that they couldn’t be who they were, and, um, they stood up and fought against the police.

Eric: And there you have it. That’s, that’s perfect.

Ken: That’s the neatest summary of the Stonewall uprising.

Ben: Oh, yay!

Ken: We’re gonna put that on every T-shirt.

Ben: Yes.

Eric: You get an A++ today, Ben.

Ben: Well, thank you.

###