Stonewall 50 – Episode 2 – “Everything Clicked… And the Riot Was On”

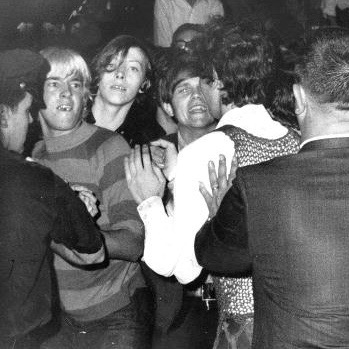

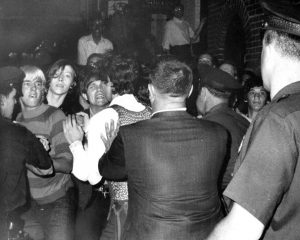

Young resistors on the first night of the Stonewall rebellion. Credit: Photo by Joseph Ambrosini/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images.

Young resistors on the first night of the Stonewall rebellion. Credit: Photo by Joseph Ambrosini/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images.Episode Notes

From Eric Marcus: At 1:20 a.m. on June 28, 1969, the New York City police raided the Stonewall Inn, an unlicensed gay club in New York’s Greenwich Village. I wasn’t there. Of these two facts I feel certain. The first one, because the police report from that night states the time that the police entered the Stonewall Inn. And the second, because I was 10 years old at the time and didn’t see Greenwich Village for the first time until I’d graduated from Hillcrest High School in Queens, New York, in June 1976. (I’m shocked now by what an incurious teenager I was back then.)

But there’s plenty about the raid on the Stonewall Inn and the subsequent uprising that’s less certain and often the focus of disagreements and heated debate. I like to think that the story of Stonewall is big enough for all the recollections and memories and inevitable myths that have taken shape in the five decades since Stonewall became a key turning point in the history of the LGBTQ civil rights movement and the birthplace of the gay liberation phase of the fight for equality.

So in this second episode of our special Stonewall 50 season, we’re bringing you multiple voices—and multiple and often conflicting memories—from people who were inside and outside the Stonewall Inn a half-century ago. Voices drawn from my three-decade-old archive and from other archival audio unearthed by Making Gay History’s team of archive rats—including some tape dating back to the first year after the raid.

Have a listen and decide which memories ring true for you.

———

David Carter’s exhaustively researched Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution (2004) remains the definitive book on the Stonewall uprising. The 2019 anthology The Stonewall Reader, which was compiled by the New York Public Library, offers first-person accounts, diaries, and articles from LGBTQ magazines and newspapers to paint a multi-faceted picture of the before, during, and after of Stonewall.

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising, Gay City News published a myth-busting article by David Carter on the uprising and its participants—who was there, who wasn’t, and why he believes it matters. Read it here. Carter is just one of a number of researchers and witnesses who have indicated that trans rights activist Sylvia Rivera was not at the Stonewall on the first night of the uprising—though as you can hear in the episode, Rivera told the story of her involvement so persuasively that it’s easy to imagine that over the years she came to believe that she’d actually been there.

Read activist and publisher Mark Segal’s myth-busting article about the Stonewall uprising and the subsequent founding of the Gay Liberation Front in this article published in the Bay Area Reporter in 2018.

In 2019 it was announced that Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera—who died in 1992 and 2002, respectively—will be commemorated with a new monument, which will be erected within blocks of the Stonewall. According to the City of New York, it will be “the first permanent, public artwork recognizing transgender women in the world.” Watch a trailer for Happy Birthday, Marsha!, a film by artists Tourmaline and Sasha Wortzel about Marsha P. Johnson’s life, including the hours immediately before the Stonewall uprising.

Who threw the first brick at Stonewall? Did any bricks even get thrown? These are just a few of the questions about the Stonewall riots that remain hotly debated to this day. The New York Times’s Shane O’Neill wrote a great piece and produced a fantastic short film about the enduring myth-making and arguments that the uprising have inspired. Have a look here.

For a more traditional recounting of what happened that night, watch the 2010 PBS documentary “Stonewall Uprising,” which can be streamed on the American Experience website here. (Please bear in mind that all of the film and video used in the documentary that depicts riots comes from other riots or is a contemporary reenactment.)

Back in 1989, to mark the 20th anniversary of Stonewall, StoryCorps founder Dave Isay produced his own audio documentary about Stonewall; you can hear it here. In addition to Sylvia Rivera, Randy Wicker, and Martin Boyce, who are featured in our Stonewall 50 season as well, you’ll also hear Deputy Inspector Seymour Pine, who led the police raid on the Stonewall Inn; Howard Smith, who witnessed the rebellion from inside the bar and reported on it for the Village Voice; and Joan Nestle, founder of the Lesbian Herstory Archives.

On June 6, 2019, the NYPD formally apologized for its actions during the Stonewall rebellion; more on that here.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History. In the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, I was 10 years old, sound asleep in my bunk at Camp Louemma in Sussex, New Jersey. I already knew I was different, but hadn’t yet put my finger on exactly why. I was a Lego nut, a big reader, a total loser when it came to team sports, and I struggled to learn how to swim. I had a girlfriend, Eva Newman, who was also 10. We looked so much alike—the same height, with thick wavy brown hair and green eyes—that people thought we were twins, which didn’t creep me out at all because it never occurred to me that that would be creepy, maybe because she wasn’t that kind of girlfriend. We held hands, played cards, which was about as far as I’d ever want to go with any girl. On that hot night in June 1969, asleep under a full moon in the New Jersey countryside, I was dreaming of my cat, Tiger Lily, who I missed terribly. That’s my story about that night 50 years ago.

But while I was safely tucked into bed at Camp Louemma, a rumbling of discontent was about to erupt into something much bigger, 50 miles away in New York City.

There are a lot of stories about that momentous night in New York City’s Greenwich Village. Stories much closer to the action than mine. Sadly, many of the people with direct experience of what happened around 1:00 in the morning on Saturday, June 28, at the Stonewall Inn, through that night and the nights that followed, have since died. So we’ve gathered almost a dozen accounts from interviews recorded in the year after the riots, from my archive from the late 1980s, and one from a more recent conversation. There are contradictions and inconsistencies in the accounts. Not everyone agrees, not everyone saw it from the same spot, memories change with time, and they rarely exactly match. But these oral histories, these personal stories, will bring this moment to life through the voices of the people who lived it.

A note on language. You’re going to hear the terms queen, scare drag, drag queen, and transvestite used a lot. Those words don’t mean the same thing as they did back then. In some cases, they’ve fallen out of usage; in others they’re offensive terms now. But it’s the language of the time and the people who were there, and we’re here to hear their voices.

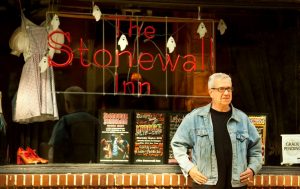

It’s time for me to step back and let Sylvia Rivera, Marsha P. Johnson, Morty Manford, Vito Russo, Craig Rodwell, Damien Martin, and Dick Leitsch tell you their stories. I spoke with all of them 30 years ago, and they’ve all since died. You’ll also hear from Martha Shelly, who is still fighting for social justice on the West Coast; from Randy Wicker, who turned 81 last February; and from Martin Boyce, who met me outside the current Stonewall Inn, to tell me about its previous incarnation.

———

Martin Boyce: My name is Martin Boyce and I’m a Stonewall veteran.

Eric Marcus: So we walk up to the front of the Stonewall. What was it like? You arrive at the front door. What happens next?

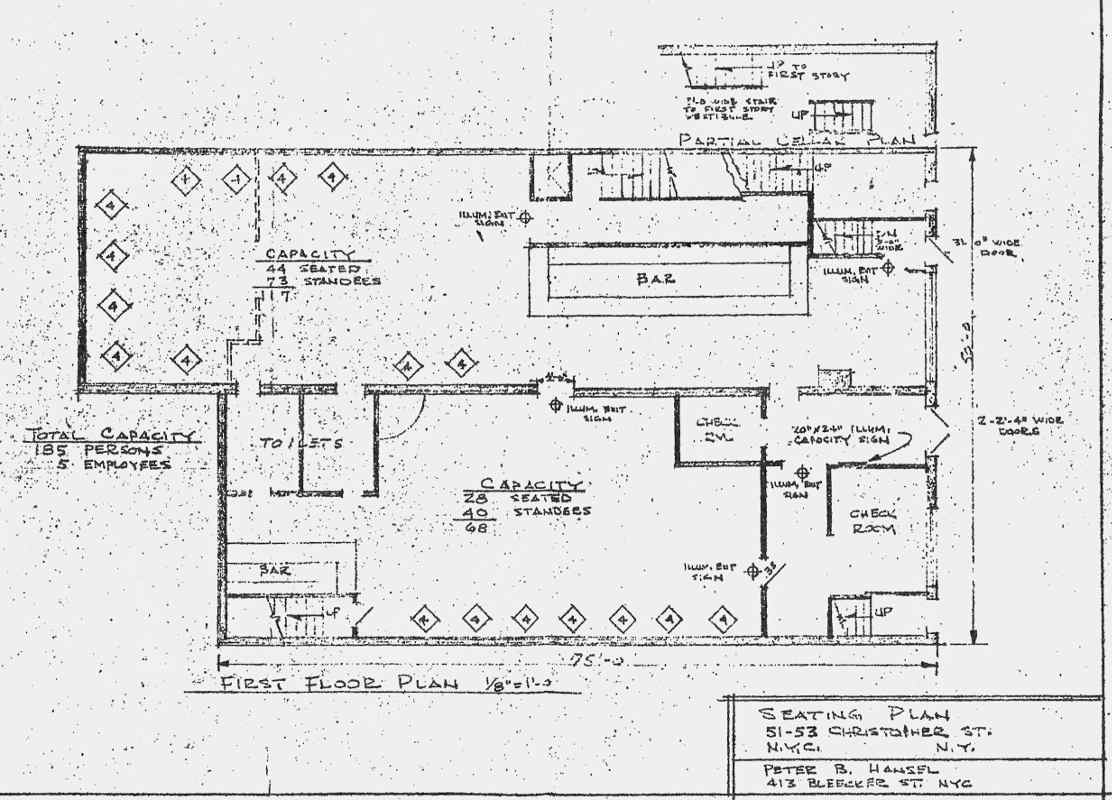

MB: Well, you arrive at the front door, and then you wait for them to say, you know, either, we’re full, or you can’t come in because of this or that—that means you just weren’t being allowed in—and if that didn’t happen, which usually didn’t happen, you would just go in. You’d, then you would sign the book.

———

Marsha P. Johnson: It was called a private club, the Stonewall.

———

Dick Leitsch: The Stonewall was an illegal club. It was very Mob-run. I mean, it was so obviously, I mean, and they used it as a money drop and all kinds of stuff like that.

———

MB: Right near the door was the table with the Mafia guy. I mean, you know, that was pretty intimidating. I mean, you know, it was like—

———

MJ: First it was just a gay men’s bar, and they didn’t allow no women in, and then they started allowing women in, and then they let the drag queens in. I was one of the first drag queens to go to that place.

———

Sylvia Rivera: Okay, you can get into the Stonewall if they knew you. And there were only a certain amount of drag queens were allowed into the Stonewall at that time.

———

DL: It was a slum. I mean, it was a, really a slum, scumbag place with the only sleazy crowd. The worst crowd of people you’ve ever seen in your life.

———

Morty Manford: It was a very eclectic crowd, which was one of the nice things about it.

———

MJ: And then they had these drag queens working there and it was just Tiffany and, oh, this other drag queen that used to work there in the coat check room.

———

SR: So this is where I get into arguments with people. They say, “Oh, no, it was always a drag queen bar, and it was a Black bar.” No.

———

MM: The place itself was pretty much of a dive. It was pretty shabby and the glasses weren’t particularly clean when they served you a drink and they were watered-down drinks.

———

DL: The Stonewall didn’t have any hot water. They washed their glasses in cold water, and they were spreading all kinds of diseases from one person to another.

———

MM: But they had a few, some lights in the back down on the dance floor area, and there was a jukebox.

———

MJ: And it was the first place I ever seen go-go boys. Because they used to have several go-go boys that used to dance on the bar at that place.

———

Vito Russo: And then you went through two swinging doors into a dance floor, where people danced, and—

———

MM: There was another bar back there and tables where people sat, and it’s just like a, you know, separate little atmosphere.

———

MB: They really had a culture in there, it was really interesting, and meaningful, because here there was a group of gays that, you know, especially the scare drags who were really persecuted, really enjoying themselves as if the world were normal, and not worrying that the sun will come up, and not worrying about tomorrow. In an amazing way, a celebration of surviving another day, living another night, maybe meeting another trick.

———

EM Narration: The Stonewall had opened its doors as a Mob-run private club in March 1967, three years after a fire had gutted Bonnie’s Stonewall Inn. That was the restaurant that had occupied the space for three decades or so. The new owners of the Stonewall, affiliated with the Genovese crime family, slapped black paint on the walls to cover the fire damage, put in a jukebox, and started selling watered-down drinks and bootleg liquor to a crowd with few other options.

Private clubs like the Stonewall were being raided by the cops with increasing frequency. Those raids were usually cleared up pretty fast with a payoff from mobster bar owners, as Sylvia Rivera explained to me.

———

SR: They would come in, raid a gay bar, padlock the freaking door. The police would leave one way, the Mafia was there, cutting in the door. They had a new register, they had more money, and they had more booze.

———

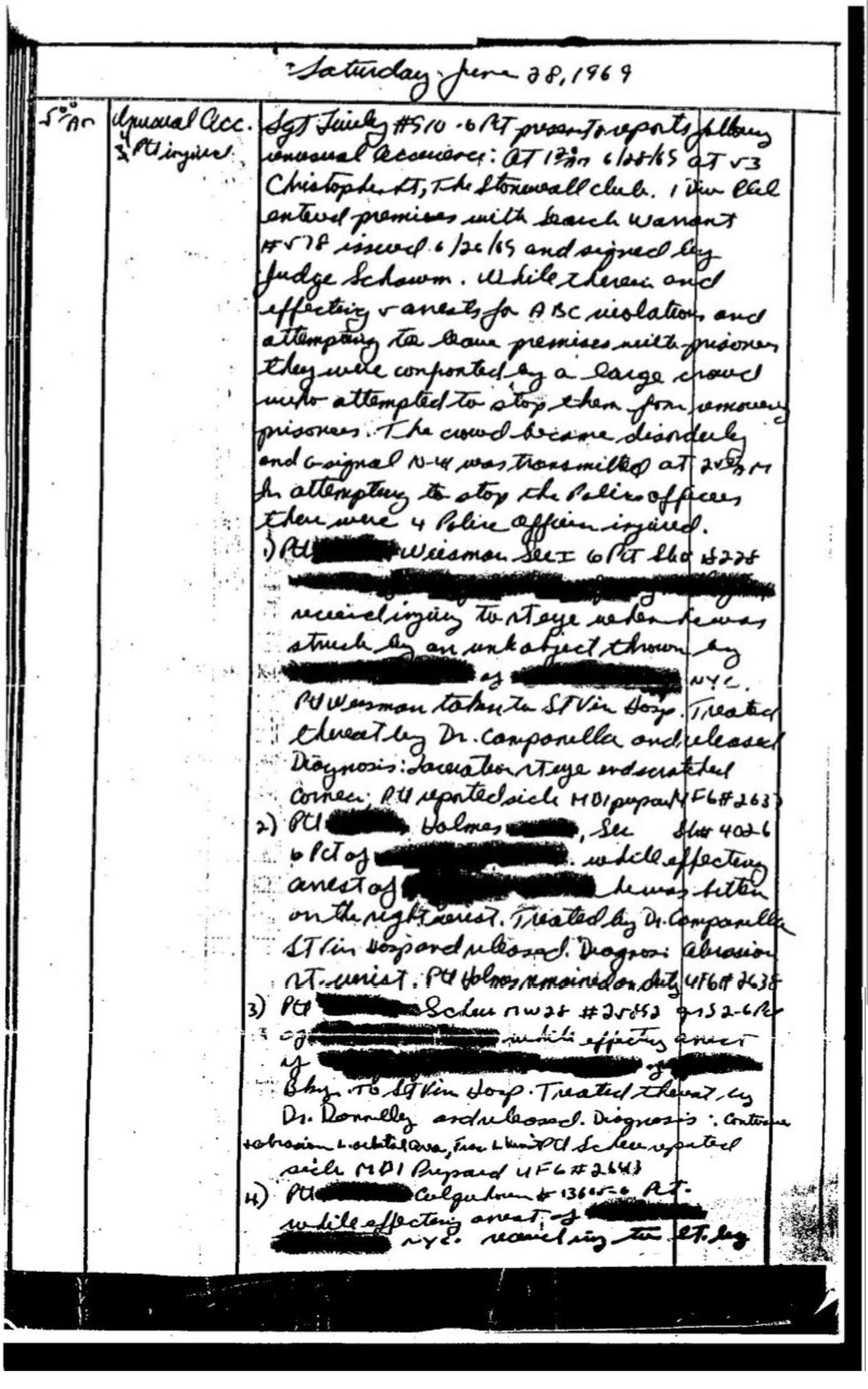

EM Narration: On Tuesday, June 24, 1969, Inspector Seymour Pine from the NYPD Public Morals Division raided the Stonewall Inn. The Tuesday night raid went off like so many others. The patrons were escorted out, the bar staff were arrested, and the proceeds were confiscated. According to Stonewall historian David Carter, one of the bar’s owners assured Inspector Pine that night that the Stonewall would be back up and running the next day. It was. So Seymour Pine planned another, more consequential raid, that would happen a few days later.

———

Breck Ardery: On June 28, 1969, thousands of homosexuals rioted in New York’s Greenwich Village section. The disorders began with a routine police raid on a homosexual bar, the Stonewall, on Christopher Street, in the heart of the West Village, commonly referred to as the gay ghetto of New York.

———

EM Narration: Morty Manford was inside the bar that night.

———

MM: I was inside and I was a patron.

———

EM Narration: He had no idea that two female undercover officers were already mingling with the clientele to scope things out, but he couldn’t miss it when Inspector Pine and five other cops came in. According to historian David Carter’s exhaustive research, the time was 1:20 a.m.

———

MM: Some very officious-looking men in suits and ties entered the place. Whispers went around that the place was being raided. Suddenly the lights were turned up. The doors were sealed, and all of the patrons were held captive until the police and the federal agents decided what they were going to do.

EM: So you were inside.

MM: I was inside.

EM: And Sylvia Rivera was there that night, too, apparently.

MM: At that time I didn’t know Sylvia Rivera.

———

SR: And I just happened to be there when it all jumped off. The police came in, they came in to get their payoff as usual. It was the same people that you saw was coming to the Washington Square Bar, too, you know, get their payoff.

———

MM: It was a nervous mood that set over the place. Everybody was anxious, not knowing whether we were going to be arrested or what was happening next. We had to line up and our identification would be checked before we would be freed. People who did not have identification, or people who were underage, and transvestites, as a whole group, were being detained. And those people who didn’t meet their standards were incarcerated temporarily in the coat room.

EM: They were put in the closet.

MM: But I, they, that’s right. Little did the police know the ironic symbolism of that.

EM: Yes, yes.

MM: But they found out fast.

———

SR: I don’t know if it was the customers or it was the police. It just, everything clicked.

———

MM: As people were released, they didn’t run away and, they stayed outside, they awaited the release of their friends. Some of the gays coming out of the bar would take a bow and their friends would cheer when they came out, and it was a colorful thing.

———

MB: This was one of the things we did. If you were not in a raid, you’d watch the aftermath. It was almost like, you know, celebrating your good luck and seeing something, like schadenfreude, I think the Germans say. It was a march of, of gays who had taken their chance by going to a gay bar, you know, and that’s the way it was. They got caught, you didn’t.

———

SR: When they ushered us out, it was nice, you know, when they just very nicely put you out the door, and then you’re standing across the street in Sheridan Square Park.

———

MM: The tension started to grow, and after everybody who was going to be released was released, the prisoners were herded into a paddy wagon parked right on the sidewalk in front of the bar. And they were left unguarded by the local police, and they simply walked out and left the paddy wagon to the cheer of the throng.

———

SR: There was a couple of dykes, they took out and threw in a car. They got out one side and—

———

MB: But there was trouble between one of the drag queens in the paddy wagon and the cop outside.

———

SR: There was one drag queen that, you know, they brought her out, and I don’t know what she said, it’s just that—

———

MB: And she kicked him. I only saw her heel kick him back, but that was enough for him to jump in the back of the car.

———

SR: They just beat her into a bloody pulp.

———

MB: You heard it. You heard it, the sounds of flesh and bone against metal. And, you know, it was a sound we all knew, we all winced.

———

EM Narration: Craig Rodwell just happened to be passing by the Stonewall with his lover Fred Sargeant that night. Craig’s account comes from an almost 50-year-old tape that we retrieved from the vault of the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division.

———

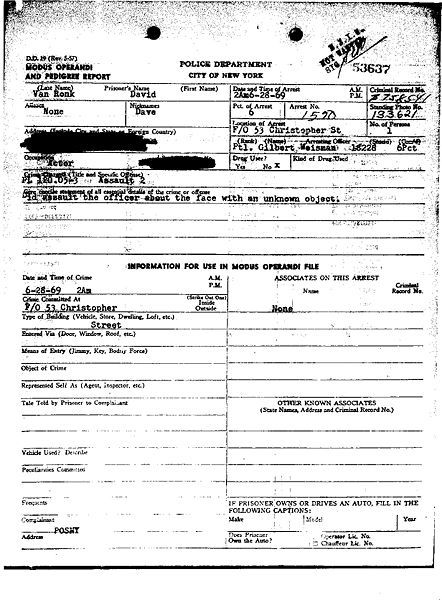

Craig Rodwell: And we were passing through Sheridan Square and we noticed this big crowd in front of the Stonewall. There was a police van out front, and a crowd of about 500 people, I would say. It was obvious what was going on. We asked people, “Are they raiding Stonewall?” And so forth. And I remember I started yelling things like, “Get the Mafia out of the bars,” or something. Fred punched me. “Shut up.”

———

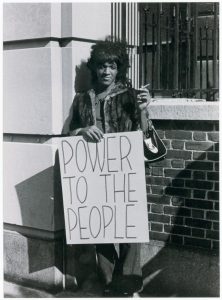

SR: He was like, “Sylvia, don’t go off.” And I’m like, “Why not?” I said, “I have to go off.” I said, “I have to be part of this.” I said, “I have to. The feeling is here.”

———

MB: “You saw what you want, you fags, now get the hell out of here. Show’s over.” And turned around like you always turn around, with complete confidence. And we started moving towards him. I mean, nobody looked at each other, nobody discussed anything. We just started moving towards him.

———

SR: Everybody’s looking at each other. “But why do we have to keep on constantly putting up with this?”

———

MM: Somebody in the crowd started throwing pennies, or some people in the crowd threw pennies across the street.

———

SR: The nickels, the dimes, the pennies—

———

CR: Pennies started being thrown.

———

SR: The quarters.

EM: Flew.

SR: Started flying.

EM: Why, why, why that? Why did people do that?

SR: The payoff. That was the payoff.

EM: Oh!

SR: That was the payoff.

EM: It was to symbolize the payoff.

SR: Yeah, you already got—

EM: Here’s some more?

SR: And here’s some more.

———

MB: I think that the riot started in a bunch of places at the same time, because it was provocation for everybody along that line.

———

CR: It sort of happened before you knew it, large objects started to be thrown. Bottles, beer cans.

———

MM: One person apparently threw a rock, which broke one of the windows on the second floor. And at the shattering of glass, the crowd sort of, “Oooooh.” It was a dramatic gesture of defiance.

———

MB: The riot was on in my section. On.

———

SR: And everything is going off really fab. I thought it was going off really fab. They locked, the cops locked themselves in the bar.

———

CR: The police began to see that the crowd was hostile, it was mad and getting madder. So they retreated within the Stonewall and locked the doors.

———

EM Narration: A policeman had been hit in the face by some sort of flying object, and it drew blood. As the cops beat a hasty retreat into the bar, they grabbed a bystander, musician Dave Van Ronk, and dragged him in, too, barricading themselves inside with guns drawn. Inspector Seymour Pine would later say it was more terrifying than any of his combat experiences during the Second World War.

———

VR: On my way home from work, I’m walking west on Christopher Street towards Seventh Avenue. And there’s this huge thing going on outside the Stonewall.

———

Martha Shelley: And we see these people who are looking younger, younger than I am, and they’re throwing things at cops. And I said, “Oh, it’s a riot, these things happen in New York all the time,” you know.

EM: Typical nonchalant New Yorker.

MS: Right, or putting it on. I said, well, you know, let’s toddle away and do something else.

———

MM: And it escalated. A few more rocks.

———

CR: And it was at that point that two or three people in the crowd went and got a parking meter, and started using it as a battering ram at the door. And it was, like, medieval, you know. Cross the moat, trying to break the castle doors down.

———

SR: The cops were, you know, they just panicked.

———

MM: Somebody stuck a gun out.

———

SR: Inspector Pine really panicked. He really did.

———

MM: Somebody from inside the bar opened the door and their arm was reaching out with a gun, telling people to stay back.

———

SR: Plus, he had no backup.

———

MM: And then withdrew the gun, closed the door, went back inside.

———

SR: He did not expect any of the retaliation that the gay community gave him at that point.

———

MM: And then somebody else, or other people, took a garbage can and set it on fire. One of those wire mesh sanitation department garbage containers, and threw the burning garbage into, into the premises. The location where this window was that was now set afire, was where the coatroom was.

EM: Burning the closet.

MM: Burning the closet. Exactly.

———

SR: I don’t know where they got the Molotov cocktails but they ended up showing up. They were thrown through the door and what—

———

EM: Who had set the building on fire?

MJ: I don’t know. Somebody set it on fire, because, you know, they, they set, the police set it on fire.

———

CR: Someone squirted lighter fluid inside an opening in the window and tried to set it on fire, and then this fire hose started coming out from the side.

———

MJ: I was uptown, and I didn’t get downtown till about two o’clock. When I got downtown, the place was already on fire, and it was a raid already.

———

EM: There was an incident with Marsha Johnson at the Stonewall riot.

CR: There was lots of incidents with Marsha and the Stonewall riot!

EM: Do you recall any of those incidents?

———

MJ: The firemen came down the street, because they had set the building on fire.

———

CR: And, meanwhile, all kinds of bottles were still being thrown. More and more chants were getting more and more vocal, and more people were coming around.

———

VR: So by the time I got there, it was basically over, and yet people were still on the sidewalks screaming at who they perceived to be the enemy, who was the owners of the bar. I went across the street to the park. There’s that little triangular park, and I sat in a tree. I mean, there was a branch. And I watched what was going on, but I didn’t want to get involved.

———

MB: Nothing in a riot is more frightening or unnerving than silence. Immediate silence.

———

MM: In those days, New York City police had a guerilla-prone cadre of their ranks known as the Tactical Police Force.

———

MB: Everybody looked around, because it was silent. Why?

———

EM: The TPF.

MM: TPF.

———

CR: The TPF arrived in large numbers.

———

MB: And you heard this thumping, like goose-stepping. And the crowd opened and there was the Tactical Police Force, armed to the teeth.

———

MM: Yeah, they wanted confrontation.

———

MB: Shields, and face shields, and—

———

MJ: The police was out there with those clubs and things and their helmets on. The riot helmets.

———

MB: Every kind of riot control piece of equipment they could have.

———

Randy Wicker: And there were reports in the press of chorus lines of queens kicking up their heels at the cops like Rockettes, you know, “We are the Stonewall girls,” and, you know, “Fuck you, police.”

———

MB: And we all made this long line of Rockette, like, kicks, and singing one of our big ditties we used to always sing when we all got drunk.

———

RW: Were you one of those that got in the chorus lines and kicked their heels up at the police?

———

MB: We are the Village girls/We wear our hair in curls/We wear our dungarees/Above our nellie knees/And when it comes to boys/We simply hypnotize—but that’s when it stopped because that’s when they charged us.

———

MM: The way they then started chasing after people, and I, and hitting people with their billy clubs, I think that may have made it greater than it was.

———

EM: What happened to you?

SR: I got knocked a little bit by a couple of plainclothes men. I didn’t really get hurt. I was very careful that night, thank God, you know, I didn’t get really hurt, but I saw other things, other people being hurt. And that’s like—

EM: By whom?

SR: By the police. It was just, like, inhumane, unsenseless bullshit.

———

MB: But everywhere I looked people were agitating. The leaders, the stronger ones, the Black queens, Latin queens, and the queens that were butch, and queens that had had enough, and lived in worse neighborhoods, and suffered enough. Everybody was going crazy.

———

MJ: Turning over cars, and, oh my dear, blocking traffic and screaming and hollering and everything.

———

CR: And they pushed the crowd back across Seventh Avenue. But the crowd just split up, went around the blocks, and just came back at it again, like charging the police. It really was amazing the police were as restrained as they were. And looking back on it, I think it was because they didn’t… It’s a particular embarrassment of the police to have in the papers the next morning they had to use tear gas, any kind of force, against a group of homosexuals. That was the whole turning point in attitudes of gay people.

John Francis Hunter: When did you first hear the chant “Gay power”? Was it that weekend?

CR: I think I was the first one to say it when Fred shut me up. Maybe somebody before had said it, I don’t know. It was that night, the first time I heard it, you know, from groups of people.

———

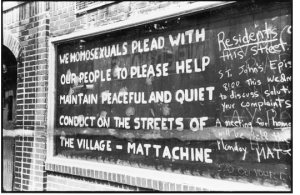

VR: And then somebody came along and spray-painted on the front of Stonewall a message to the community to quiet down, that this was our neighborhood and we weren’t going to let them take it away from us, and, you know, everybody should calm down and go home.

———

EM Narration: The fighting died down, the sun was coming up, 13 arrests were being processed at the precinct, and Martin Boyce and his friends were spent. All rioted out for the time being, they watched a new day dawn over Greenwich Village.

———

EM: So it’s dawn, and you’re sitting on a stoop across the street, where we’re standing now.

MB: Right.

EM: And what did you see as the sun began to rise?

MB: As the sun began to rise, you know, with my head down and tired, I kept looking up and, and I saw this queen who was exhausted, bruised a little, I believe, and couldn’t go on any more, was just on a stoop, exhausted but at peace, because near her was a cop who was also exhausted, that made no attempt to bother her. The riot was really over. Still, the street was glistening. It was one of the most beautiful things I ever saw. The whole street just like diamonds, but in reality it was broken glass, the smell of the smoke of burning garbage cans was there, all those smells that a riot make, even a certain kind of sweat. It was ugly and beautiful. It was something, though. All of these bad images were enveloped in a certain kind of beauty that was coincidence, and haphazardly, but then so was the riot, so maybe it was a metaphor for that, because I don’t know. But I did notice it. I did stop and register it and memorialized it. And I remember because the one thing I always said afterwards, even shortly after Stonewall, was the end of that night. And how that street glistened.

———

EM Narration: The first night of unrest was over, but the uprising had just begun. Martha Shelley had managed to miss the riot. She was the one you heard saying that riots happened all the time in New York City. After toddling off, as she put it, she had hitchhiked from the Village to her lover’s house in New Jersey, woke up the morning after the raid, and headed back into the city for a Daughters of Bilitis meeting.

———

MS: I don’t remember what it was. I was part of running the meeting. And I don’t remember what the speech was. Then I found out what happened. From lack of sleep and exhaustion, I was sort of feverish, and I lay on my couch that evening, thinking, We got to do something. We got to do something. We can’t just let this pass. We should have a march.

———

EM Narration: Meanwhile, the police went to the Mattachine Society’s office to ask—beg—that the riot not continue another night.

———

DL: Anyway, the cops came that day, the Saturday, came flying up to Mattachine, “Help, help, make these people stop! Make them leave us alone!” And, well, first of all, they were defensive. You know, “We had to do this because, because, because…” Yes, I understand you because, because, because, that’s what you’ve been doing for all these years. You got to expect people to get upset sooner or later. You got to stop sometime. “Oh, we’ll stop, just please get them off our backs, make everything calm down.” So, we didn’t know what to do, so we just went down and walked the streets and talked to people.

———

CR: And then on Saturday night it was much the same thing, starting about nine, crowds started to gather in the area. Sort of small groups on the sidewalk. And then around 11 or 12, they started taking over the street and stopping cars from coming through, unless there were gay people in them. A few fires were set. But generally it was an angry mood. A lot of chanting, a lot of hand-holding, a lot of assertion of being gay. And that was a way of saying, we’re tired of hiding, tired of leading two lives, tired of denying our basic identity, denying ourselves. The newfound pride, really, a collective pride in our identity.

———

VR: For the next two or three nights, there were constant confrontations. The police would come along and sweep the area.

———

Damien Martin: The second night, I for some reason had to go up Sixth Avenue in a cab, and I passed by right there where the old Women’s House of Detention used to be, and they had police lines up, and they were keeping the crowds back, and there were these gay and lesbian people chanting. And the main thing I remember about it was the look on the cops’ faces. They had that look that you sometimes see with someone who has a trusted pet who suddenly just bit them. There’s that astonishment and fear at the same time, that is not like terror or anything, but just astonishment as a large part of it. And I got a great pleasure out of the look on their faces.

———

EM: What did you say to the police?

MJ: We just were saying, “No more police brutality,” and, “We had enough of police harassment in the Village and other places.” Oh, there was a lot of little chants we used to do in those days.

———

CR: And on those later nights there was a lot more people and we took over the whole area and closed down the streets. The third or fourth night, I don’t remember which night. It was right up here at the corner of Greenwich and Christopher. And I was up at this corner, and Marsha had climbed to the top of the light pole. I don’t remember specifically whether it was platform heels that night or Joan Crawford fuck-me shoes or what, you know. Anyway, it was a cop car pulled in and parked on Greenwich Avenue sort of right under where the light pole is, and Marsha just threw that thing right through the windshield of the cop car. And I was only a few feet away, and I can remember the cops. And they knew it came from up there, you know, but they didn’t care. They just opened the back door and just grabbed the nearest faggot, pulled him in, and then the other started driving, you could see him just beating with a nightstick, you know.

———

Breck Ardery: By the end of the week scores of police and rioters had been injured, many were arrested, and one man, a cab driver, was dead.

———

EM Narration: That cab driver was driving down Christopher Street when rioters blocked his way and rocked the cab. He died later in the hospital of an apparent heart attack. His was the only fatality related to the riots.

———

Breck Ardery: Almost every homosexual who was in New York at the time of the Stonewall rebellion has his own private memory of what took place.

———

VR: We would sit on a stoop on Christopher Street and wait for them to come and move us along and then we would go around the block to where Julius’ is and come back and sit down again, until they came and moved us again. And this got to be like a two- or three-day game. People were, like, setting fires in wastepaper baskets on Sheridan Square and chanting and screaming.

EM: You were primarily an observer.

VR: Yes. Yes. I had no connection or knowledge that there was in fact the beginnings of an activist movement going on right around that issue.

———

EM Narration: Maybe Vito Russo didn’t know an activist movement was springing out of the uprising, but as the dust settled, and June gave way to July, organizers called meetings almost immediately.

———

MS: And I went to Jean Powers and said, “We should have a march.” And Jean said, “Well, if Mattachine Society agrees, we’ll co-sponsor it.” Mattachine was having a town hall meeting—town hall, it turns out, was this building that held about 400 people.

———

RW: They asked me to speak at the Electric Circus, it was a big disco in the East Village.

EM: This was after the riot?

RW: This was during the riot, or right at the time of the riot.

———

MS: And there were all these gays that showed up at the meeting to talk about what was going on.

EM: You showed up as well.

MS: Yeah, with the proposal that we hold a jointly sponsored march.

———

RW: I got up and said I didn’t think the way to win public acceptance was to go out and form chorus lines of drag queens kicking your feet up at the police.

———

MS: And Dick Leitsch, who was the head of Mattachine, wasn’t really into it.

———

RW: I was just beginning to speak and one of the bouncers at the Electric Circus found out that it was a gay thing, that the guy up there talking was gay, and somebody standing next to him, he said to them, “Are you one of them?” And the guy said yes, and he began beating the hell out of him, and this riot broke out in the Electric Circus.

———

MS: When he asked for a vote—how many people are in favor of holding a march?—every hand went up.

———

RW: The kid was only about 21 or 22 years old, and he said, “All I know is that I’ve been in this movement for three days and I’ve been beaten up three times.”

———

MS: So he said, “Okay, if people want to run a march,” you know, “March committee meets over there.”

———

EM Narration: Next week, we’ll bring you the story of that march and the first Christopher Street Liberation Day March, which was held to mark the one-year anniversary of the Stonewall uprising. If not for that anniversary march, which was the culmination of intensive organizing that the riots inspired, Stonewall might very well have been lost to history.

Many thanks to everyone who makes Making Gay History possible: executive producer Sara Burningham; producer Josh Gwynn; assistant producer Mo LaBorde; administrative and special projects manager Inge De Taeye; scoring, mixing, and sound design by Rae Kantrowitz; photo editor Michael Green; and our social media team, Cristiana Peña, Nick Porter, and Denio Lourenço. Thanks also to our intrepid researchers Brian Ferree and Brian DeShazor. Special thanks to Jenna Weiss-Berman. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division, the ONE Archives of the USC Libraries, and the Pacifica Radio Archives. Season five of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, the Calamus Foundation, Irwin and Andra Press, and a special thank-you to everyone at Stonewall Kickball in Washington, DC, for your generous donation.

Stay in touch with Making Gay History by signing up for our newsletter at makinggayhistory.com. Our website is also where you’ll find previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature.

So long—until next time!

###