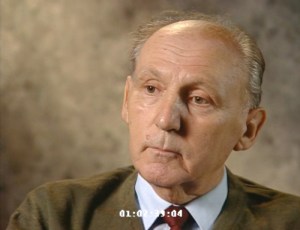

Stefan Kosinski

Stefan (Teofil) Kosinski, Warsaw, Poland, 1960. Via USC Shoah Foundation interview, November 14, 1995. Credit: USC Shoah Foundation.

Stefan (Teofil) Kosinski, Warsaw, Poland, 1960. Via USC Shoah Foundation interview, November 14, 1995. Credit: USC Shoah Foundation.Episode Notes

Polish teenager Stefan Kosinski was beaten, tortured, and sent to prison. His crime? He fell in love with a Viennese soldier serving in the German army. When the soldier was sent to the Eastern Front, Stefan sent him a love letter, which was intercepted by the Nazis.

Episode first published February 13, 2025.

———

Archival Audio Source

RG-50.030.0355, oral history interview with Teofil (Stefan) Kosinski, courtesy of the Jeff and Toby Herr Oral History Archive, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C. For more information about the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, go here.

———

Resources

For general background information about events, people, places, and more related to the Nazi regime, WWII, and the Holocaust, consult the online Holocaust Encyclopedia of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM).

- Stefan Kosinski’s entire testimony can be viewed on the USHMM website.

- You can watch an additional three-hour interview with Kosinski, also conducted by Dr. Klaus Müller, on the USC Shoah Foundation website here (registration for their Visual History Archive is free). Click on “Images” in the bottom right corner of the video screen to see additional photos and documents related to Kosinski’s story.

- Damned Strong Love: The True Story of Willi G. and Stefan K. by Lutz Van Dijk (Henry Holt, 1995) is available for online borrowing here.

- For German readers: Van Dijk also edited Endlich den Mut … Briefe von Stefan T. Kosinski (1925–2003) (Finally the Courage … Letters from Stefan T. Kosinski) (Querverlag, 2015).

- In this brief clip, Van Dijk discusses the nightmares and fears of persecution that haunted Kosinski till the end of his life (Stories That Move/YouTube).

———

Episode Transcript

Klaus Müller: Can you tell us, uh, your name and where you come from and when you were born?

Stefan Kosinski: Yes, I do this. Uh, my name is Teofil Kosinki, Polish, but for American should be maybe a little difficult to pronounce, Kosinski, so it’s better I say Teofil Kosinksi. I was born in Poland in Torún, this is Polish name, and in German was Thorn. This is more in north Poland. My father was, uh, worker on the railroad. And my mother, she works from time to time, uh, cleaning some houses. We were together five children and my mother and my father.

———

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History: The Nazi Era.

Teofil Kosinki, also known as Stefan, was born into a Catholic family in northern Poland in 1925. His parents rented out rooms in their small house so they could feed their five children. When the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939, Stefan’s father was sent to Warsaw to fight. Poles were barred from secondary education so Stefan went to work as a delivery boy for a baker.

In 1995, Stefan was interviewed for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. The interviewer was Dr. Klaus Müller, who began researching the Nazi persecution of LGBTQ people in the early 1990s. Dr. Müller has played a pivotal role in collecting and preserving survivor testimonies.

Stefan remains the only person who was persecuted for his homosexuality during the Second World War who provided full recorded testimony of his experiences in English.

He begins by telling Dr. Müller that two years into the war, he landed a job singing in a theater. Poles had to be off the street at night, but Stefan got special permission to be out after curfew so he could travel home from evening performances. He was 16 years old at the time.

———

SK: Theater was very nice, I liked this climate, this atmosphere. There were dancers, singers, nice people. In the theater you could forget, you see, the war. Because especially for me, I had no chance, nothing, no cafes. It was wartime boring. During the evening it was dark, close house, no gas lamps, nothing. War. Exactly war.

KM: And then when you worked for the theater, you met at one point someone who became very special for you.

SK: Yes. It was one day when I left theater. Uh, I cross, uh, as usually the same place, uh, to make some shopping. And I feel that somebody watched me. At the moment I said, maybe some, uh, policeman like this because it was dark. I didn’t see.

And, uh, I went and he followed me. And I see there is, uh, some, uh, uniform, some soldier. I didn’t know what he wants from me. He smiled to me, never happened before, that. And he started to ask something from me.

And then, “Hello, how are you?” How… “Nice, yeah.” “Oh, shall we go maybe to drink some coffee?” I’m looking. German invited me coffee? My heart was trembling. I was so excited. I didn’t know, maybe when I refuse him, they will happen something wrong.

I agree. I went. And then when we were inside, “So you went and you make now shopping?” “Yeah, I bought”—I showed him my bag with this, yeah. “Your parents are living here, your family? “Yes. My parents are living here. My father is not here. My father is, I don’t know, maybe in Germany, and, uh, I was born also here.”

“You are born here? You are not German?” “No, I am Polish.” “Oh God, what you are doing now?” I said, “Don’t worry. I have the passport until 12 o’clock.” “Oh God, that’s good. But maybe we go out.” I think he was afraid will somebody hear that he speaks with me. And we went out, went out. He asked me in which direction I’m going home. I showed him.

And then he asked me, “May we see us again?” “When, why?” “I would like to meet you.” I asked, “Why not? We can do this.” “But where?” I ask. “You see here, here at this station.” It was, uh, in the station, railway station in the middle of the city. It was very good place. We, uh, fixed, uh, exactly, I remember it was after two days at the same place. And he came after my performance. He came.

And then I, I, I took him because I knew places. He asked me whether I know some places because here is not so good to walk for him and for me.

He said, “You look very nice, you are very nice boy”—for the first time. And then he told me, “I’m not German. I’m…” “You are not German? Who are you then?” “I’m Austrian.” “Austria? Vienna?” “Yes, I’m Vienna.” “Oh.” And I feel me a little better. It is completely different, like, uh, German.

His name was Willi Götz. I will never forget his name. And I wanted to—because he was so, he was so kind, so sweet to me—I wanted also to be sweet.

I met him, it was on exactly the date, November 4, 1941. It was snow, it was cold, the winter was so strong. He took me in some places for the first time, and it was very pleasure. And then we went to this shed. We played. It was romantic. And then when I went home, I couldn’t sleep. I dreamed because it’s happened something with me completely different.

KM: What happened? What was different for you?

SK: Different for me, it’s changing my life. I feel something. It was feeling like love. It was like love. But don’t think that there was real sex. No. There was playing, kissing. Maybe the sex come also, of course. I was young. I feeled it.

But it was very, very pleasureful time. We couldn’t see us each day, because you couldn’t receive not every day the permission, but so long he could, he came, and he brought me always something—some sweets, some special ration card. For this card I could buy some pastry because for Polish people it was absolutely forbidden, uh, to receive pastry. I received once even shoes because he has seen that my shoes for the wintertime was no good.

Home was big scandal, especially my brother. My brother feeled there is something wrong because I brought shoes. I brought once shirt, and he knew that this shirt was from soldier. He asked me something, “What’s happened?” “I don’t, don’t, and don’t worry. Oh, what I’m doing is my business.” He was very angry, said, “I’m older than you. I promise father to take care of you. So I must know.”

KM: Did you tell him?

SK: Later, when the change was so big, even my mother feel something, because I ask very often, “Mother, I need white shirt.” This, my mother complain, “I have no soap. You change every day. What f—? I cannot wash.” “Mother, I must look very nice.” But it was not for theater, it was for my friend.

And uh, one day, of course, when my brother drank a little, I said to him—his name was Kazimierz—I said, “Kazik, you must understand me. I fall in love in soldier.” “Oh my God. Why, you don’t like women?” “No, I like men like you like, uh, women. I like men. You must understand me.” “No, this is only for the moment. Uh, you’ll find a girl probably,” etc. “Especially with German, you know what’s happen. It’s very danger.” “No, it’s not danger, it’s so good.” “No, you can be sure. You must stop it. I tell mother.” “Don’t tell this mother. I ask you very much. Don’t do that.” He didn’t say this mother. But from this time he changed his, uh, behavior, uh, toward me. And our relation was not so good as before.

I was 17 years, uh, old at this time.

KM: How old was Willi?

SK: He was, you know. About maybe five or six years older than me, but he looks very handsome, very strong. I never seen his picture. I ask one day for his picture, but he said, “It’s better you will not have, it should be very danger for you and for me.”

He told me also, he said something, “You see, you must be very carefully because Hitler, the rule, um, you receive for this kind of love is very danger. You must be very careful.” I say, “What for? We are doing nothing.” “Don’t tell anybody that we meet us, that we are coming here. It is, it will be very danger. Please believe me, I am older. I know better.” He told me that.

But, uh, it was in April 1941 when we met to our place. He brought me something new, and then he was very nervous. “What’s happened?” At first I thought maybe some, uh, somebody has seen us. Uh, I ask him. “No, nobody’s seen. You know, I am sending to the Eastern Front of war.” “Oh my, to Russia? My God, to Russia.” I heard that this was the worst front, uh, in the war.

“What we have to—?” “Nothing. You must wait for me. I promise you, the war will be not longer. When the war is, uh, is end, the war, you will come to Vienna. I, I will try, uh, uh, to leave with you together. Wait for me. Wait, wait.”

I give him my address and I was waiting. I was waiting for his letter, but I haven’t received. I was very sorry. Very sad. It was so long time, four months, I haven’t received a letter.

Then when I was, uh, in the theater one day, I have seen German newspaper, and there was written the address for the Wehrmacht, for the soldiers who are on the East Front there. I wrote secretly the address, and then I was fighting with myself whether to write to Willi or not to write.

And I, I wrote a letter in the, in my, uh, young, uh, German language. It was mentioned, uh, that I, I love him. I’m waiting for him. I pray for him that he come back. And “I hope you will come back as soon as, and, uh, I will be very glad. Please, uh, give me some news because I’m so anxious about you. I cannot sleep, I cannot work.” And at the end, “With many kisses, your friend, Theo,” I wrote.

And it was a little, uh, naivete to, and especially I putted my sender. Usually, I couldn’t do that, but, uh, I was fighting. If I send without sender, what will happen? Maybe the letter will not come back, and if come back, then I will knew that he’s not there, so that I send the letter with my sender.

KM: And what happened then?

SK: I was waiting for reply, but reply never didn’t come, never. Only one day, it was, uh, September 19, 1942, I was working morning at this, uh, uh, manufacture. And the boss called me and told me that I have to go to the Gestapo. I asked him, “Me, to Gestapo, what for?” I was so honest, I did nothing.

When I went to the Gestapo, I remember this uniform, this black uniform with his red here in this arm. He asked me first for the name. I told him that, and then he took a typewriter. He started to write. I was sitting so in front of him when the paper came through down. I read from, from other side. It was written, “Haftbefehl.” In English it is “Order for prisoner.” Like this.

Oh. Then first moment I thought I will fall down. And then he said, “You’ll stay now.” “What for?” I began to cry. “Don’t play here theater. Don’t play.”

And then he called somebody. They took me to the cell. It was downstairs in the cellar. And there was on—the furniture was only wooden, uh, bed and some tub for, as a toilet. And that’s all. And I had to wait. And, uh, the whole time I was sitting the night and was thinking, what’s happened, what for, what?

And the next day, when I was called again to him, he showed me the letter, this letter which I wrote to Willi. “This is your letter.” I was very honest, of course. I said, “This is my letter. I wrote this to him.”

“You, you wrote this letter to German? You are, you, you loved him? You had—” “I wrote him, was very good, yes.” And then said, “Where did you meet him?” He wanted to know exactly where we met us, what we have done, in which way. I say, “We have, we seen only once or twice.” I, I lied. I tried to lied.

He show me some, uh, uh, pictures, other pictures of soldiers. I think maybe they wanted to know that, uh, I had maybe ma—more soldiers, not only one. It was the reason. But I hadn’t, I had only Willi. And it was true. But they beaten me. They wanted to know, and maybe they should kill me because they didn’t believe me.

They came two men, and they beat me. When I couldn’t breathe, nothing, I couldn’t speak, they bring, they brought water, they poured water in me, and began once more, again and again, always. And this, and, and always I heard only the, um, “You pig, you Sau-Pole [Polish pig], you Sau [pig], you…” So many bad words I cannot translate into English. “Du Sau-Schwule [you faggot pig], du Sau, du Polacken [you Polack], du Stricher [you manwhore], du Stricher, du Arschficker [you assfucker].” Terrible. So many words I have never heard before that.

And every day there was given only once per day—first, in the begin, I didn’t eat nothing, I wanted only to drink, only water. Sleep I couldn’t also, because I was so beaten, swollen on the, my back and ass was so full of wounds with blood, and when I was lying, then only on my, my stomach.

Every day the same, maybe about two weeks. Every day the same question. At the last one they gave me something to sign, I don’t know what. For me it was, I could sign everything only to be, uh, uh, to be free. And it’s happened so two weeks. After two weeks I signed. I signed something. What? I don’t know.

They took me by a special closed car. I was brought to this okrągły, to this round prison. I was putted to the cell with six or seven prisoner. Each prisoner has received a special card. I have received card, it was written, “Paragraph 175.” I didn’t know what it mean. And I showed to everybody. “Oh, that is for Arshficker, that is for the gays like this, for the homosexuality.” And since this time I was not human. I couldn’t, uh, uh, sit at the table when the began. They treated me very, very bad. And I was sitting there until December 5, 1942.

On December 5, 1942, I, somebody opened the, open the door. The Wachtmeister took me to the judge. I remember there was only, uh, my mother, no people, and me, and, uh, maybe five or six in black dresses—the judges. There were shouted and cried. I have to be isolated. I’m, I have demoralized German military, me, Polack, uh, and how I could do that. I must be punished. I must be punished for long time. And I was 17 years old.

And they stated me, they punished me for five years exactly Zuchthaus. It’s very hard prison. And immediately on, and then you see, I met my mother. I couldn’t speak. You can imagine how was the feeling, my mother and me.

When I came to the cell first I cried, but later I had to go. Uh, I was sent to Koronowo. Koronowo was not far from Torún, maybe 50 or 60 kilometer. It was the worst prison in Poland before the war and during the war. Only for Polish and Jews prisoners.

They cut my hair. And I was sent to the cell with about 40, uh, prisoners. There were maybe about five or six Jews together with me.

KM: Were there other prisoners, uh, who were imprisoned because they were homosexual?

SK: There were, of course, many.

KM: Did you talk about your situation?

SK: No, you see, because first of all, I didn’t knew that this is something, this is homo—I didn’t hear, I didn’t knew this word. Later after war, then I knew what mean homosexual and gay, etc. But me as a, I was really very, um, shy boy, and I didn’t know this. I didn’t talk about this and nobody even asked, uh, so that I never talk about the homosexual in the prison.

———

EM Narration: The prison conditions were dismal. It was overcrowded and there wasn’t enough food. Stefan suffered a leg infection that was left untreated. When prison authorities needed someone who could speak and write in German, Stefan volunteered, which earned him slightly better conditions. But it wasn’t long before he was transferred to a series of other prison camps.

Then, after surviving a two-week forced march in subzero temperatures, he ended up in an island prison near Hamburg. As the war was coming to an end, he managed to escape. After Germany’s defeat, Stefan hoped to look for Willi in Vienna, but travel to Austria was difficult. He spent two years as a displaced person in the American zone of Allied-occupied Germany, where he worked as a waiter. In 1947, his mother begged him to come back to Poland. He gave in and returned.

———

KM: Did you ever talk with your family about these years and, and how did they react?

SK: Never. And, uh, they gave me never chance to speak about this and they never gave me this, uh, to feel it.

KM: But did you talk with your, your parents or your brother about the experiences in the prison, what you went through?

SK: No, no, no, no, no. We, we, we like it this subject away. Even when we went sometimes to family, to other people, to other family. “Oh, you spent so, so like in prison. What was the reason?” And I said, “Don’t talk about, this is very bad time. Don’t mention it in this way.”

KM: Did you tell your mother about the conditions in the prison or you never—?

SK: Oh, no, no. I couldn’t, uh, to, to, to, to make hard to make—no, no, no. Never. No, this subject was overmitted.

KM: If you look back today, how do you feel about what happened in those years?

SK: Sometimes I’m wondering that I am still alive, that I succeed this very bad time, and, um, sometimes I’m wondering what kind of reason that the people that do so, and they are available to, to, to, to torture the people, young people like me. I, I didn’t kill nobody. I didn’t did what, that I was in very good friendship with somebody, with soldier? That is the reason that I have to go to prison?

Sometimes it is so… They are so very heavy thoughts. I am Catholic. I can forgive the German, but never forgot. I never forget. This is too difficult to forget.

———

EM Narration: Life in post-war communist Poland as a gay man with a criminal record proved difficult. Stefan completed his studies in economics but couldn’t get a job in his field. And he couldn’t afford adequate medical care to treat his lasting health complications from being tortured and imprisoned. Despite multiple applications, he never received compensation for his time in prison.

In 1990, a German gay advocacy organization put Stefan in touch with Lutz Van Dijk. He offered to write Stefan’s story. Stefan bought a used typewriter and started corresponding with Van Dijk, who captured Stefan’s recollections in a young adult novel. It’s called Damned Strong Love: The True Story of Willi G. and Stefan K. and was published in Germany in 1991 and in the U.S. four years later. Sales of the book provided Stefan with much-needed additional income. It also gave him a sense of community as he responded personally to every letter he received from readers.

Van Dijk also helped Stefan search for information about Willi.

———

KM: Do you know what happened to Willi?

SK: Uh, this is so complicated. Me together with Lutz Van Dijk, we tried to research everywhere. In Poland, in, um, Germany, in Austria, and, uh, no news, nothing.

But you see, once I have also this documents. I received—it’s stupid, there’s the same name and the same, uh, everything is okay, even the age should be maybe the same Willi Götz. Only the question is, he was born not in Austria, in Germany. That was written in Germany. And what more, there’s written he’s, he is dead on the begin of—I was arrested in ’42 and he’s dead ’43. I’m not sure.

———

EM Narration: Stefan never found out for certain what happened to Willi. To the end of his life, he was haunted by the fear that his love letter might have led to Willi’s persecution or even death.

Stefan Kosinski died in Warsaw in November 2003. He was 78. His book was published in his native Poland four years later.

———

In our next episode, Pierre Seel, a French Catholic teenager whose stolen watch lands him in the hands of the Gestapo.

———

This episode was produced by Nahanni Rous, Inge De Taeye, and me, Eric Marcus. Our audio mixer was Anne Pope. Our studio engineer was Michael Bognar at CDM Sound Studios. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Thank you to our photo editor Michael Green, our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham, and our founding production partner, Jenna Weiss-Berman at Pineapple Street Studios.

The interview with Teofil Stefan Kosinski was provided courtesy of the Jeff and Toby Herr Oral History Archive at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

To learn more about the people and stories featured in our episodes, please visit makinggayhistory.org, where you’ll find links to additional information and archival photos, as well as full transcripts.

This special series on the experiences of LGBTQ people during the rise of the Nazi regime, World War II, and the Holocaust is a production of Making Gay History, in partnership with the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale University.

I’m Eric Marcus. Until next time.

###