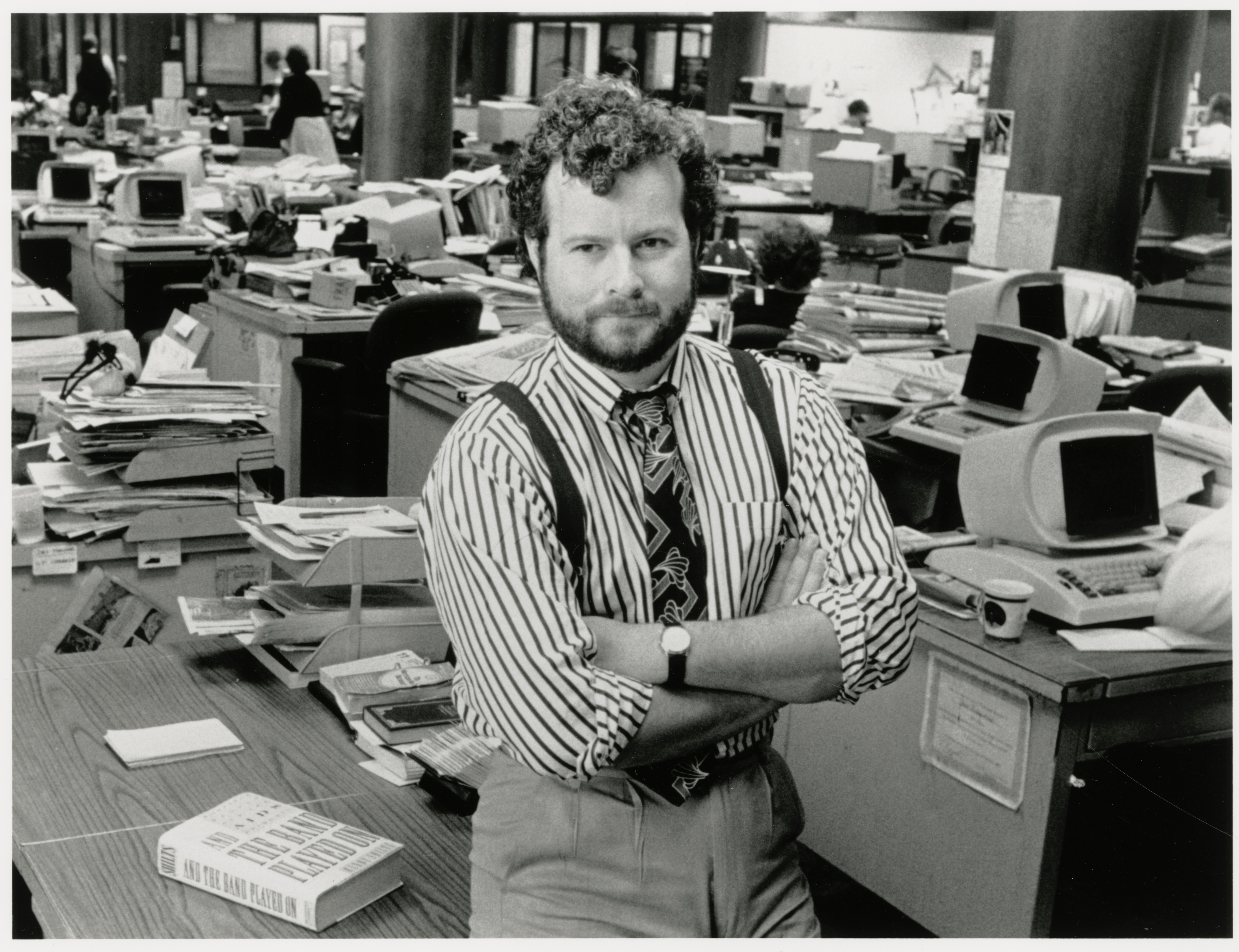

Randy Shilts

Randy Shilts, 1987. Credit: Scott Sommerdorf / San Francisco Chronicle / Polaris / Randy Shilts Papers, Hormel LGBTQIA Center, San Francisco Public Library.

Randy Shilts, 1987. Credit: Scott Sommerdorf / San Francisco Chronicle / Polaris / Randy Shilts Papers, Hormel LGBTQIA Center, San Francisco Public Library.Episode Notes

Out gay journalist Randy Shilts desperately wanted to work for a big-city newspaper. No one wanted him.

But reporting on the AIDS crisis brought him the success and fame he craved—and more than a little controversy.

———

For a concise overview of Randy Shilts’s life and work, read his New York Times obituary and this SFGATE profile, and watch the short documentary Reporter Zero. For a deeper dive, have a look at the 2019 biography The Journalist of Castro Street: The Life of Randy Shilts by Andrew Stoner (whom you can hear discuss the book here).

Shilts attended the University of Oregon, where he served as president of the Eugene Gay People’s Alliance, a campus group. When he ran for student body president, the local paper noted his association with the “homosexual group.” His election slogan was “Come Out for Shilts.” (As Shilts mentions in the episode, the Eugene Gay People’s Alliance invited speakers like Morris Kight and Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, who were featured in Making Gay History episodes of their own, here and here.)

In 1974, Shilts won his first William Randolph Hearst Award for a story about drag queens in Portland; you can read the student paper version here and the Eugene Register-Guard newspaper version here. For the Advocate he wrote about everything from gay rights in Oregon and national anti-gay initiatives to dating and sexual dysfunction. In the magazine’s February 25, 1976, issue he published “Alcoholism, A Look in Depth at How a National Menace Is Affecting the Gay Community,” an awareness-raising piece that contributed to the growth of gay and lesbian substance use treatment services and AA groups in the years that followed; read the article here (scroll down to page 5).

In 1977 Shilts was hired as an on-air reporter by KQED’s San Francisco TV station to cover gay topics. The first story he did was on Harvey Milk, the openly gay politician who served as a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors until he and Mayor George Moscone were assassinated on November 27, 1978, by former colleague Dan White. Despite a full confession, the jury found White guilty only of the lesser charge of manslaughter, not murder. Jurors were swayed by White’s claim of diminished capacity due to depression caused by a change from a healthy diet to one filled with sugar-packed foods (famously derided as the “twinkie defense”).

When Dan White was sentenced to just seven years in prison, a shocked community revolted in what became known as the White Night riots. Members of the San Francisco Police Department retaliated by attacking patrons of a gay bar. Shilts covered it all. And in 1982, he published a biography of Milk titled The Mayor of Castro Street: The Life and Times of Harvey Milk, which he discussed in this 1982 audio interview with Tommi Avicolli.

Shilts’s work as an out gay TV reporter made him a recognizable figure in San Franciso’s gay community. The May 1980 issue of the short-lived local magazine Boulevards included Shilts among the ten most eligible gay bachelors in town; see the too-cool-for-school photo that accompanied the piece here. He also made appearances on the radio show The Gay Life and other gay media.

In 1981 Shilts finally achieved his goal of working at a prominent mainstream newspaper when he was hired by the San Francisco Chronicle, first as a reporter and then as a columnist. He was the first openly gay news reporter in the country to be hired as an out journalist. Reporter Joe Nicholson (not Nichols, as Shilts says in the episode) of the New York Post was the first openly gay big-city newspaper reporter, but he came out after he’d been hired. In the interview, Shilts gets the circumstances of Nicholson’s coming out wrong: Nicholson came out not in 1977 during Anita Bryant’s anti-gay crusade, but in 1980 after a homophobic gunman’s attack on a New York City gay bar. Learn more about Nicholson here.

Shilts was one of the first journalists to report on HIV/AIDS. His opinions and reporting style made him a polarizing figure and he often clashed with others in the LGBTQ communities. During the early years of the AIDS crisis, he denounced San Francisco’s gay leaders as “inept” and “a bunch of jerks,” accusing them of hiding the emerging epidemic. In 1984, Shilts famously supported closing the city’s gay bathhouses, angering advocates and apolitical folk alike. Find out more about the bathhouse controversy here.

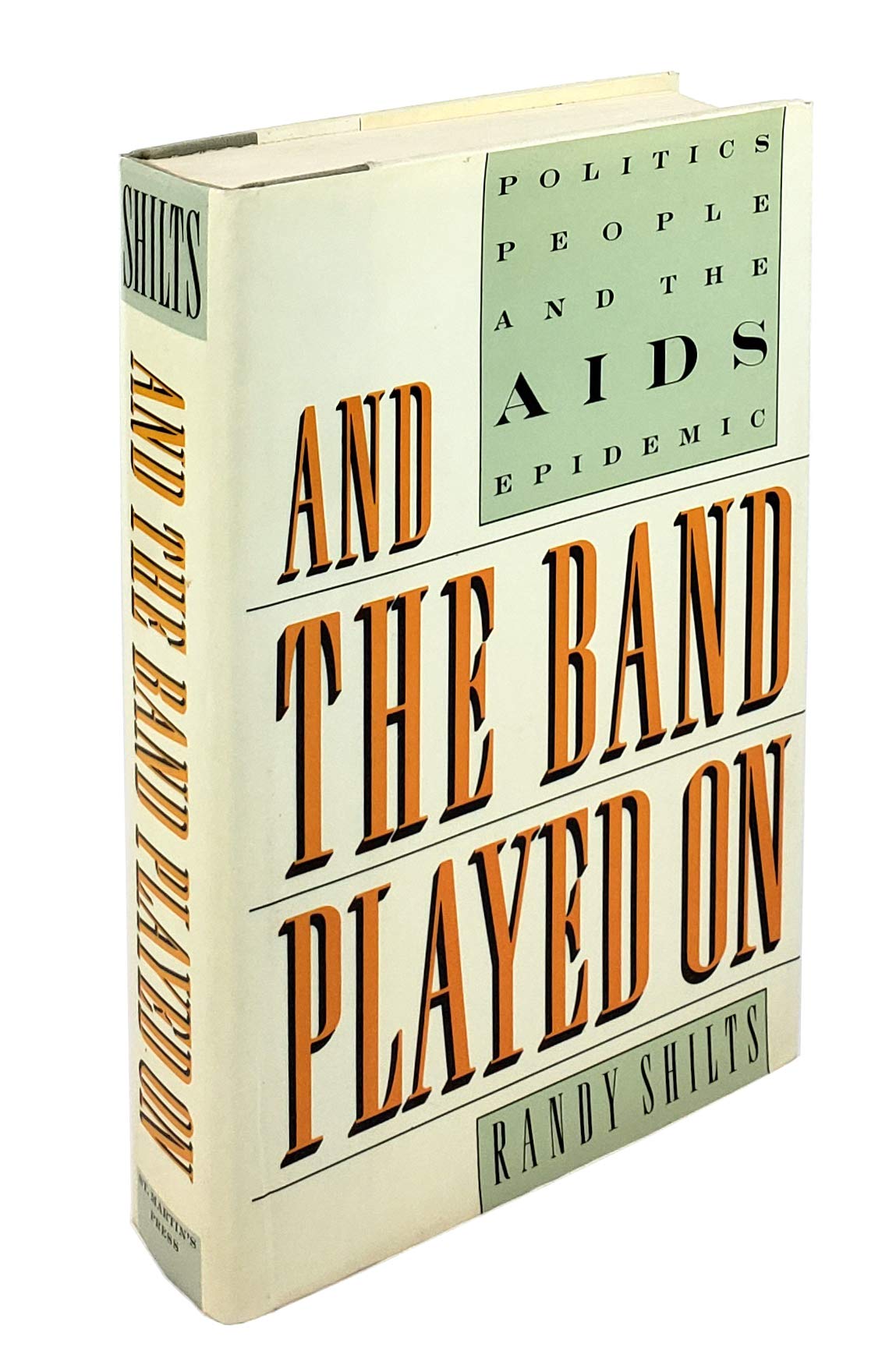

In 1987, Shilts published his second book. And the Band Played On, a comprehensive history of the early AIDS epidemic in the U.S., received much acclaim and went on to become a bestseller. But Shilts’s casting of Gaëtan Dugas, a Québécois flight attendant, as Patient Zero was disputed and finally condemned as false. You can watch Shilts discuss his Patient Zero theory here. The 2019 documentary Killing Patient Zero sets the record straight and aims to rehabilitate Dugas’s reputation. Despite the controversy, And the Band Played On remains an essential account of the early AIDS years, and in 1993 it was made into a star-studded HBO film.

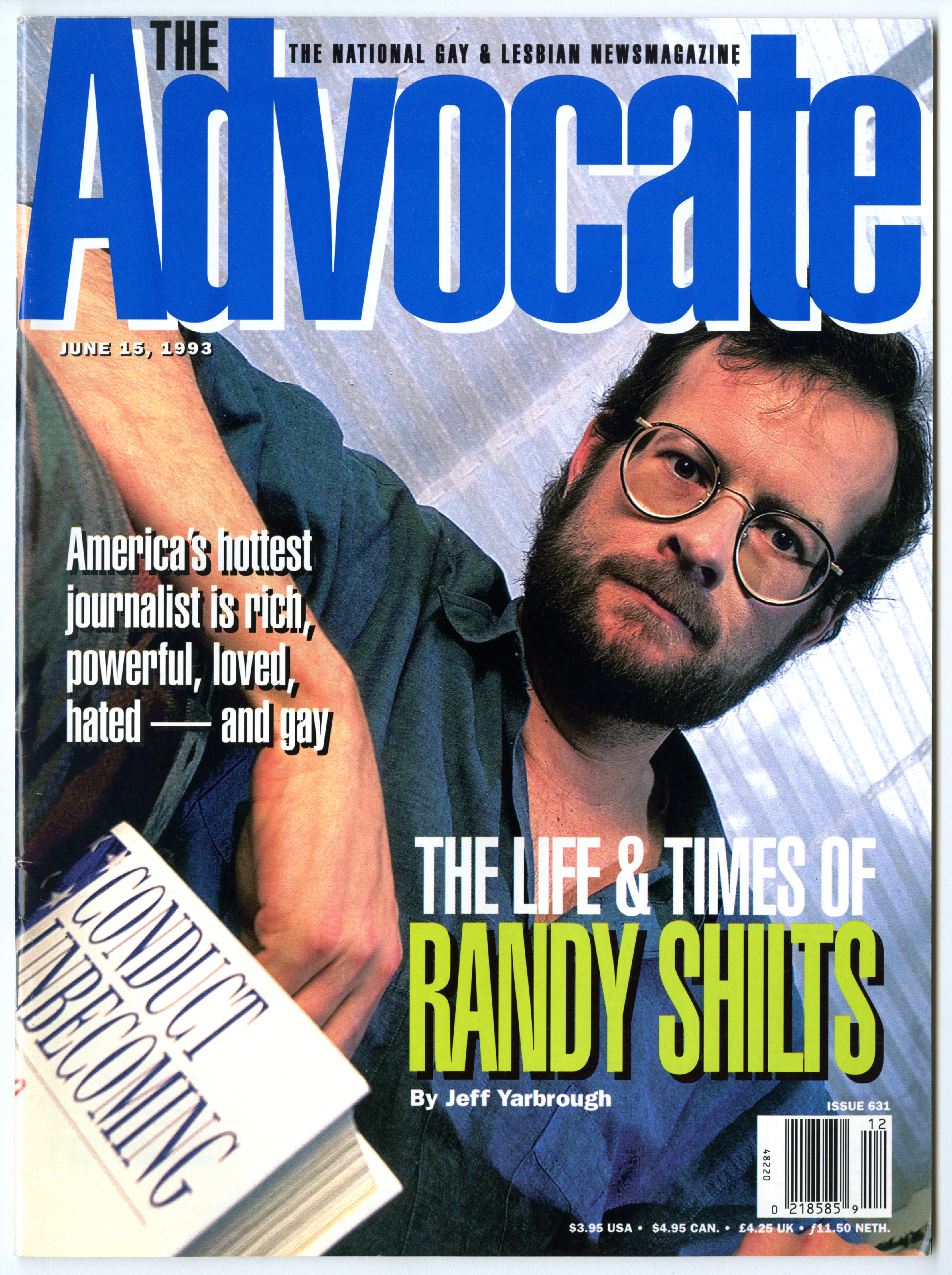

Shilts’s final book, Conduct Unbecoming: Gays and Lesbians in the U.S. Military, was published in 1993. During the final stretch of writing, Shilts contracted pneumocystis pneumonia, a common opportunistic infection for people with AIDS, and the final paragraphs “were dictated from his hospital bed.” Listen to Shilts discuss Conduct Unbecoming with Terry Gross on Fresh Air here or watch him on Charlie Rose here.

Shilts died from AIDS-related complications on February 17, 1994. You can watch his final 60 Minutes interview here and view his memorial service program here (one of the speakers was Perry Watkins, who was featured in this Making Gay History episode).

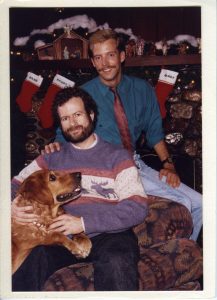

For further research into Shilts’s life and work, explore the Linda Alband Collection of Randy Shilts Materials, courtesy of the GLBT Historical Society. The collection is filled with professional and research papers but contains personal items as well—like these holiday cards and party invitations (be sure to scroll down to the invite for a birthday party for Shilts’s dog, Dash).

Shilts has been memorialized by the LGBTQ community in many ways. He has seven panels on the AIDS Memorial Quilt. The Publishing Triangle bestows a yearly Randy Shilts Award for Gay Nonfiction. He had his own AIDS Awareness trading card. And in his beloved San Francisco he has a bronze plaque on the Castro District’s Rainbow Honor Walk.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus, and this is Making Gay History.

Randy Shilts got bitten by the bug his senior year of college. He wanted to be a journalist. But not just any journalist. He wanted to be a big-time big-city newspaper journalist. There was only one problem: Randy was gay and out, and in the early 1970s there was no such thing as an out gay journalist at a mainstream big-city newspaper.

But Randy was determined—and fierce. By the time I met him in 1989 he was the leading journalist in the U.S. covering the AIDS crisis, and he had two books under his belt: The Mayor of Castro Street about Harvey Milk, the assassinated San Francisco city supervisor, and the award-winning bestseller And the Band Played On, a gripping history of the early years of the AIDS epidemic.

But in his adopted hometown of San Francisco, Randy’s unflinching coverage of the AIDS crisis earned him a lot of critics. Early on in the epidemic, the city’s gay leadership bristled at the unwelcome attention they feared would derail the community’s political progress. And when Randy called for the closing of the city’s gay bathhouses as a way to slow the spread of HIV, he was vilified by those who weren’t about to give up their hard-won sexual freedom. Randy was accosted on the streets and shouted at in restaurants.

So here’s the scene. It’s the evening of Tuesday, September 12, 1989. I arrive at Randy’s modest, but comfortably decorated house on Saturn Street overlooking San Francisco. Randy’s hyperactive golden retriever greets me at the door with a cold nose and a wet tongue. The dog’s name is Dash, after hard-boiled detective novelist Dashiell Hammett. Before I even have the chance to unpack my equipment, Randy is talking a mile a minute, interrupting himself, interrupting his own interruptions.

He shows me into his living room, takes a spot on the sofa, and tries to get Dash to settle down, without much success. But I manage to clip my microphone to Randy’s sweater and we’re off and running.

———

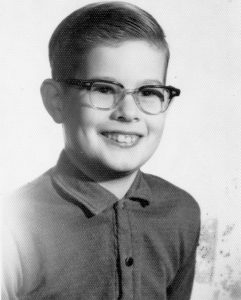

Randy Shilts: ’69 I graduated from high school. So Stonewall happened three weeks after I graduated from West Aurora Senior High School, Aurora, Illinois. And so, um, and then I was very, the only time, and this is what’s so different now than, than even when I was in school, is that, um, you know, you grew up with never hearing anybody talk about being gay. And the one time, I think, before I was 18 I heard the word “homosexual” was in this incredibly enlightened context where my sociology teacher, who was the teacher I admired beyond all other teachers, who was so neat and really liked me, where she said, “Maybe they’re not criminals. Maybe they’re just sick.” And then she stopped, realizing that what she had said was hopelessly radical and said, “Well, at least that’s what some people think.” You know, like, that was, you know… And I’ll never forget that, because it was, I knew so well that I was gay then, and had…

Eric Marcus: This is in ’69.

RS: Yeah, and had, oh, and had, you know, numerous sexual exploits in Boy Scouts and everything like that. So I knew, it was very… So I knew I was gay, but of course very self-alienated about it. And then you hear that from somebody you admire, and that’s it.

EM: Do you recall what you thought when she said that you were, you were just sick as opposed to criminal?

RS: I think what I thought was that it was the most liberal thing that I’d heard at the time, too—that, gee, maybe I’m only sick. Um, but there are so many levels, you know, that your psychology works at when, you know, you’re, you know, you’re a fucked-up 18-year-old closet case, or 17 at that time.

And I left Aurora the minute I could, and, at the end of 1969, and hitchhiked to the West Coast and, uh—with this woman friend of mine, and she had mentioned that there were lots of bisexuals and, on the West Coast. And so, and that was obviously a big drive for me to do it. And, but I was also a hippie, so I had my hair long and was smoking marijuana and listening to The Moody Blues and reading Hermann Hesse, and doing all the things that, you know, staring at the three-dimensional album cover of Satanic Majesty’s Request, and…

EM: The what, I’m sorry?

RS: The three-dimensional cover of Satanic Majesty’s Request. It’s a Rolling Stones album that had a three-dimensional cover on it that you’d get stoned and stare at it and see the little pictures of the Beatles in the corners.

And so I fell into the counterculture in, in Portland, where I lived, and was very hippie, but still couldn’t bring myself to come out. It was just still, it was this taboo and it was violating this taboo that I couldn’t make myself do. I had no links to my home, to my family. You know, I was very independent, but I just couldn’t bring myself to do it.

EM: Were you in school at the time?

RS: Yeah, I was at the—I had to work my way… My parents were pretty poor and we were very—because I was a hippie and they were very conservative, we were estranged for two or three years and didn’t talk—so I put, had to work my way through college and went to a community college for two years. And it was in my second year of community college, though, that I came out, that… I had my last heterosexual affair with my philosophy teacher. And one reason I had an affair with her was because in philosophy class, in every one of her classes, she would bring in, um, people from the local Gay Liberation Front in Portland to, to speak. And I figured, well, gee, I’ll, you know… And so one of my attractions to her was that I could meet… It was… My, my last heterosexual affair was just all a ruse to be able to get to meet other gay people.

And then that was—and I met, um, one of her gay friends who was in the Gay Liberation group. And we, and we, we talked and, and it was the first time… It was just like in, in one week I was able to put the whole gay thing, shift it from, from being my problem—and society is right and I’m wrong—and I was able to really pretty much adapt the political analysis that, gee, I’m alright, it’s society that’s wrong. And so it was a week after I met this guy and was able to sort of talk about this stuff that I was teaching a class in, um, anthropology, cultural anthropology. I was going to be an anthropology major then.

So what I did was change at the last minute and invited all my friends and then had, uh, two women and then this other guy from the Gay Liberation Front. And then I was on the panel. And I introduced the panel and said we were all gay and we’re going to talk about what it’s like to be gay in America. So all my friends were there. And I told all my friends that day. I told everybody in my life that day. I told my parents within, in, in, about a year later.

EM: Do you remember what day that was?

RS: Yeah, it was May 19, 1972.

EM: How did your class react?

RS: Uh, everybody was great. I mean, everybody was real cool. I didn’t lose, I didn’t lose—I only lost one friend. It was very easy, everybody was very accepting.

And then I moved to Eugene and, uh, the next fall I went to the University of Oregon. And I was, um, I became very just totally involved in the gay movement and was the president of Gay People’s Alliance, which was, I think, that was formed in 1970. It was one of the oldest gay campus groups in the country.

EM: Which one is this?

RS: The Gay—Eugene Gay People’s Alliance at the University of Oregon.

EM: How many people were in your group?

RS: Boy, we’d have meetings of up to a hundred people. Most meetings had just 20 or 30. And the first meeting of every semester would be packed because everybody would come to see who else was gay. And then about 80 percent would disappear back into the woodwork of the school. And then, um…

EM: That sounds very familiar.

RS: Yeah, and that’s, and the, uh… But then we did a lot of rap sessions. And that was very crucial to my integration as, I think, in terms of integrating a positive self-image and, and, uh, and understanding.

EM: How so?

RS: In terms of really talking out how our problems as individuals, being gay and accepting ourselves, how they related to a broader, political framework of, uh, of us within a society in which we were brought up to dislike ourselves and to doubt ourselves. And so it was just this real intensive talking.

And, uh, so then we did things like put on the first gay dance at the University of Oregon. And then we put on the first—it was the gay-straight sock hop. And it was all sixties music. And we, we allowed straight people and made—you know, we were very liberal.

And then we did the Gay Pride program and did speakers, and we had Morris Kight come up…

EM: Oh, you did?

RS: And Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon…

EM: Back to the dances just for a moment. Were you, did you experience any resistance from the school over doing these dances?

RS: No. No, ’cause I was very powerful in student government so they really couldn’t fuck with us.

EM: You had a very serious foundation as a troublemaker early on in your career.

RS: Yeah. Yeah. Once I understood the whole gay issue politically then it all fell into place almost right away, because it just gave me a political context to understand, you know, what was going on.

EM: Did you, um, must have decided at some point that you were going to be a writer/journalist.

RS: Well, that came very late, though. I was an English major by the time I was at the University of Oregon and I was going to write great novels. And then I was, um… But I couldn’t write a simple declarative sentence because I was an English major, and they don’t teach you how to write, they teach you how to read. And so then I, uh, took a journalism class because a roommate said, “Oh, well, they’re good at teaching grammar.” And so I took a journalism class just to learn grammar and then I was so good at it, if I do say so myself, and I just took to it so well—that was in my fourth year of college that I did that, and I stayed in an extra year and got my degree in, in journalism.

And in November 1974 I got a William Randolph Hearst Award for a story about drag queens in Portland. And, so I always wanted to write about gay stuff. And then my second award was another Hearst Foundation award for a story about discrimination against gay people. It was called “In Hiding,” it was a very dramatic story where I interviewed all kinds of closet cases and, you know, prominent people who, you know, had to conceal who they were.

EM: In Portland?

RS: Portland, Seattle. So I worked real hard in journalism school. And got tons of awards, was real good, got great grades. But was—I’d been very out front about being gay, and, uh…

EM: Did anyone say then—as, as was said to me when I was in journalism school—being out is gonna really hurt your career?

RS: Um, graduate student types were very blunt and just said, “You know, you can’t, you can’t do this, you’re just not… This is not gonna work. You’ll never have a career.” And I was real adamant that I, that I was gonna be out front. And once you come out, especially in a very public way, the way I was in the, you know, so involved in campus politics and stuff that you can’t go— it wasn’t an option. So in Oregon, so let’s say it’s, so what happens is ’75 comes, I’m about to graduate, and I can’t get a job anywhere.

EM: Did you send your resume out?

RS: I sent out my resume and people who didn’t have grades as good as mine were, who didn’t have my awards, who didn’t have, you know, hadn’t done as much on the campus newspaper, they were getting job offers. And I wasn’t.

EM: What did that make you think?

RS: Well, it was just so clear that it was discrimination. Then at the same time I had, I had… Because I had won those two awards from the Hearst Foundation I was rated as one of the top eight college journalists in the United States when I graduated. And so that was, they took the top eight college journalists and you participated in a national writing championship. I won second place in that. And then the night that we won, I took everybody out to the gay bar because it was here in San Francisco and I had been before. And then the next, and then they freaked out, the Hearst people freaked out and then a few weeks later they took away the award. They said they made a judging error. A thousand dollars, and they canceled the check before I could cash it.

And, um, it was so devastating because, um, I realized then that I wasn’t going to be able to get a job and so I was going to make it as a freelancer. Because I swore when I got out of college was that I’d never make a penny except through my writing. And so that was my resolution that I stuck to.

EM: How did you finally get your first job?

RS: My first job was, uh, well, I was freelancing and I went to Portland, and I was gonna freelance for Portland publications and, uh, and then for the Advocate. That wasn’t panning out as a professional, um, thing, because there just weren’t enough publications in Portland. So then I moved down here. And the Advocate wouldn’t give me a job, but they more or less assured me that I’d be able to have 600 dollars a month worth of stories. So I just came down here and worked my—and just devoted myself to writing for them and then within five months then was, became staff writer at the Advocate.

I was hired there in April of 1976, and then got to cover gay stuff, which was fun. I thought it was lots of fun. I always wanted to work in the mainstream media, but it was a great… I was covering stuff that I liked and it was a great training ground.

EM: Did it make you crazy, though, that, here you were, one of the eight top journalists of your—in the United States…

RS: … and I was writing for this publication that had all these dirty classified ads in it. That I couldn’t send the publication to my parents that I worked for because it was all filled up with “Gay white man wants somebody to piss on,” you know? And the, uh, it was so embarrassing, you know, ’cause it was… Sometimes I go back and read the little diary fragments I wrote back then. And what’s really striking about ’76, ’77, ’78 both is the ambition—I was real ambitious. I just knew—it was never a question of whether I was going to make it because I knew I was. And I just worked around the clock and every day of the week. And, and was always freelancing something and, and working. But just the anger, the rage, just the horrible rage.

And then with me, part of my story becomes that I start drinking over it and stuff, and so that’s, uh… Because I think I was just probably born with alcoholism in my genes, but I think it came out a lot sooner than it would have.

EM: Who did you rage against?

RS: Sort—at the beginning it was just this big nebulous “them,” you know, all the places where I couldn’t get work. It becomes more specific as time goes on, because I’m at the Advocate and doing good stuff and then I get my, my break, which, the big break was in February 1977. KQED had Newsroom, which was a nightly news show. And so they wanted to start covering gay stuff. They were going to be the first because nobody covered gay stuff. Oh, the Chronicle, the Examiner, TV stations back then never covered gay stuff. It’s like it didn’t even exist. So, uh, they were gonna be the first people to do this. And so they wanted somebody who was openly gay to do it, somebody who they could say in a press release was gay because they knew that would be good press.

So anyway, so I got it, even though I wasn’t that—I had a horrible voice. I’m not really meant for TV. But the, uh…

EM: You must have been thrilled.

RS: Oh, it was just the thing. I was, I had arrived. The St. Paul Pioneer Dispatch—which won the Pulitzer, um, for AIDS a few years back, assholes—they ran a thing, “Homo Hired to Be TV Reporter.” I probably still have that around somewhere.

The ratings were miserable on the show, but strategically it became very good for my career, because people into news, um, all read it, so all the editors and opinion leaders and, uh, you know, in the news business got a sense of me real quick.

My first story was about Harvey Milk, 19—February 1977, for a story about Harvey Milk and the District 5 race. I knew one thing about Harvey Milk, that he was just this great story. He was just going to be the best story. And, uh…

EM: Because he’s, he was a character.

RS: He was a character and he was gonna win. And it was so, uh, and he was… But also he articulated a vision. He was an idealist. He was a visionary in the true sense of the word. And then the Castro Street was so fucking exciting. I mean, it was just so exciting to be gay and be on Castro Street. It was just neat.

EM: Why?

RS: Because it was, we were gonna create a new world. The new world, the new way of being gay was coming from Castro Street, so…

EM: What was the new way to be gay?

RS: The new way of being open about being gay, of not having to be hiding, of being powerful, asserting your power. Uh, when people, when gangs came in to beat us up, you know, we organized our own street patrols. And, uh, you know, that kind of responding. Not being the sissies anymore. It was so different. And being butch and being, you know, the whole thing of totally recasting what being gay meant in America. And we were doing it on Castro Street. And the rest—and in the gay world everybody else in the world was following us. You know, we created it. We were the Mecca. And so it was so, uh, uh, heady.

And it was such, it was a great time to be a journalist because you knew that you were just—I knew I was writing about… And that’s what—this gets back to my anger—that I knew this was so fucking important and the Chron—nobody was covering it. You know, they’d cover the news stuff about, you know, Harvey getting elected and stuff. And that’s when, because by—once I’d been at the TV station for a while, it was clear, you know, everybody said I was a great reporter and then, because I come from print background, so I did intelligent things.

EM: You knew what a story was.

RS: Yeah, exactly. And it was a different—it wasn’t like a TV guy. And so the, uh, and that was then the rage because then I couldn’t get a job. So I applied at the Chronicle and at the Examiner, and everywhere. Nobody would hire me. I really wanted to write for the Chronicle. I really wanted to be in the mainstream and, and be back in print. And I did real… and then I started applying at TV stations.

This was in 1978. My, my break came in commercial TV the week after the riot, that the riot happened after the Dan White trial. And they, everybody realized that they needed somebody to explain this so KQED, no, KTVU Channel 2 let me start freelancing for them. And I freelanced for them for about a year, until a, uh, magazine that was a short-lived magazine here called Boulevards Magazine had the ten most eligible gay bachelors in San Francisco. It was in, uh, like May of 1980. And I was the number two after Armistead Maupin. And, uh, the, the news director saw that, freaked out, told my best friend at the station that it was a disaster for my career, that I shouldn’t be, you know, you know, that it’s one thing to be gay but you shouldn’t talk about what you want in a boyfriend. And, uh…

EM: Which you did in the article.

RS: Yes, of course, that’s what you do when you do a most eligible bachelor! You know, “Better like rock and roll,” and, uh, “better like The Rolling Stones,” and something like that. And he didn’t, he stopped using me as a freelancer.

EM: It must have made you crazy!

RS: Well, it was just so fucking weird, and then that was around the time that—well, this is the whole, the big despair hits then. The, uh, the KQED Newsroom, the news show, got canceled in August of ’80 so I went on unemployment. And then that’s when I wrote the Harvey Milk book, basically because I didn’t have anything else to do. Nobody would hire me.

And so I just kept, so I did the Harvey Milk book and then I finished that, and then just a few weeks after it the city editor… They had a new city edit—or he’d been at, city editor at the Chronicle maybe a year, and he was, loved TV people and loved the show I was on and hired me.

EM: Were you the first openly gay Chronicle reporter?

RS: I was the first openly gay news reporter in the country except for a guy named Joe Nichols at the Post had come out in Anita Bryant in ’77. I was the first person who was hired “as open,” you know, so I, this is, you know, whatever that distinction is. But certainly at the Chronicle.

EM: It’s a distinction. It’s a big distinction.

RS: It is. And so that was in August of ’81. And in fact, it’s ironic, because, you know, AIDS had been disc—detected just, you know, weeks before then. But I didn’t start doing major stories… The big story that started everything—and it was in March of ’83 and I talk about it in my book—that story where there’s this study about one in 300 gay men in the Castro had been diagnosed with AIDS by then. Well, this was when everybody thought it was media hype and it wasn’t real. And one in 300—now it’s one in 10—had been diagnosed with AIDS. But then that was so shocking. I thought it was real important.

And then I found out that all these gay leaders had had this study for two months and they hadn’t done anything with it, hadn’t done anything to tell people about it. “Oh, we’ll release it through appropriate channels,” which meant, oh, the gay press. Or they have to have another meeting to decide about it. And, you know, and everybody’s out there getting fucked in the bathhouses every weekend, and thinking that AIDS is a media hype and they weren’t releasing this information.

So I wrote it up. And when I was writing that story, I had, the president of the Alice Toklas Democratic Club called me up and said if I print that story, they’ll put barbed wire around the Castro. Um, people called up my book publisher, somebody called my editor at St. Martin’s, Michael Denneny, and had Michael Denneny call me in San Francisco to try to talk me out of doing this story. And I mean, I got, did nothing but answer phone calls all day from people, gay political leaders, trying to get me not to do that story.

EM: What did you tell them?

RS: I just told them I don’t get paid to not write news stories. You know, to me it was just so obviously, the news value was there. And just their way, you know, and, and—oh, it just made me so mad, you know. And, you see, and that’s the thing is because, see, if I had been serving the, what was then perceived as the political interest of the gay community, I would not have written about AIDS in 1983.

But from a journalistic point of view it was so obviously a story. So that started it. And then in 80—and then within a couple of months of that there was the big, the first bathhouse thing, which was, the gay leaders had had a meeting with bathhouse owners, and asked them to put up posters warning people about AIDS. And the bathhouse owners refused, and just said… They walked out of the meeting. They said, “We’re not gonna put up po—You’re blaming us for AIDS, we’re not gonna do it.” I mean, this is really… And so I heard about it, about the meeting, um, and again they didn’t want the story. Uh, you know, people heard I was going to do the story. “Oh, don’t do this. You can’t even talk about the bathhouses.” So I just did a story.

And at the beginning I wasn’t for closing the bathhouses, I didn’t… But I just thought it was an issue that you had to talk—you couldn’t talk about this disease and not talk about bathhouses. I used to go there. I know what happens. And, uh, I worked in the bathhouses one of my summers in college, in, in Portland.

EM: I mentioned to a few people along the way that I would be interviewing you for this book. People had very strong feelings about you.

RS: Yeah.

EM: Why?

RS: Well, it’s funny because people say, “Oh, you must like controversy.” And I hate it, I hate being… I’m very sensitive and I, my feelings get very easily hurt. And, uh, so they’re hurt a lot.

And then some of the stuff that comes out. I mean, I’ve lived my whole adult life being open about being gay and then I get people hassling me who are, who’ve never, for being an Uncle Tom or something or being a self-hating gay. That’s what they do. And I just think, my god, you’ve never, you know, these people who’ve never had anything comparable to, to, to being, you know, living the kind of very public gay life that I have.

It just gets me mad, you know. It’d be better if I didn’t. Uh, sometimes I do internalize it too much. I spend a lot of time with my therapist talking about this.

EM: That’s a good thing to have one. I’d be worried if you didn’t given the, the position you’ve been in.

RS: No, I don’t get any better, but then on the other part of me thinks, well, I think the reason my writing is good when I do the important stuff is that I’m sens—that the sensitivity comes out and I’m able to draw, you know… If I became an asshole, if I became thick-skinned about that then I’d be thick-skinned in my writing and I wouldn’t be as sensitive.

EM: You still have a heart.

RS: Yeah, exactly.

EM: How do you like being a celebrity?

RS: Oh, it’s weird. It’s just weird. It’s really, it’s interesting being a gay celebrity and being… So, it’s interesting, today I was in buying my washer/dryer for my house at the river. And a straight guy, he has a wedding ring on, and this is Santa Rosa in the appliance store, and so he was writing down my name from the credit card and he said, “Oh, you’re not the Randy Shilts?” “What?” And I, and I said, “Oh, yeah.” And he said, “The author? Gee.” And it was, it was like, and it was, and it’s, what’s interesting is that, uh—and I haven’t quite got—it’s like, that people don’t see me as being a famous queer, they see me as being famous. Which, that’s what blows me away. Because I would have expected the gay thing to be much more overriding. But, uh, and maybe that’s just because it’s not as shocking to be gay anymore.

EM: The intro now is “Bestselling author Randy Shilts…” as opposed to “Gay reporter…”

RS: “Gay…” And it always used to be. In fact, people used to joke that my whole, that I should get my name changed to “Gay Reporter Randy Shilts” because it was always this four-word unit, you know? Now it’s bestselling author, and it’s lots more respectability than I ever thought I’d ever have.

———

EM Narration: By the time I left Randy’s house I was spent—he was intense—but I also had a new friend and mentor. Randy encouraged me to call whenever I needed help. And I did. Several times, when I hit a wall with my book and needed a pep talk. Randy was also generous with his research and shared with me a big box filled with FBI documents that he’d secured through the Freedom of Information Act. One of those documents corroborated Frank Kameny’s story about the FBI showing up at the 1961 organizational meeting for the Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C. It was all spelled out in the report in black and white.

What Randy didn’t share was that he was HIV positive by then. He’d found out in 1985, but he waited more than seven years, after a collapsed lung landed him in the hospital, to share his AIDS diagnosis with the world. According to the Los Angeles Times, Randy kept his diagnosis secret for fear it would detract from his role as a reporter on AIDS issues. He said, “Every gay writer who tests positive ends up being an AIDS activist. I wanted to keep on being a reporter.” I remember wondering at the time about Randy’s decision to keep his diagnosis under wraps and feeling troubled by how defensive his explanation was.

What was much more troubling was a made-up key protagonist in And the Band Played On. The person was real; he was a French-Canadian flight attendant by the name of Gaëtan Dugas. But Gaëtan’s role as Patient Zero, as Randy characterized him—an HIV super-spreader who traveled the U.S. like a Typhoid Mary Johnny Appleseed—was false. A recent documentary called Killing Patient Zero examines the story in sad detail. It was explosive publicity about Patient Zero that helped propel Randy’s book onto bestseller lists. I can only speculate that Randy’s profound wish for success and fame undermined his better journalistic instincts.

Randy Shilts died from complications of AIDS on February 17, 1994. He was 42 and survived by his partner, Barry Barbieri. Randy’s memorial service program included a final message to his critics, a quote from a letter Randy wrote to the Advocate magazine a month before he died that read, “And while we’re talking conclusions, hopefully, history will record that I was a hell of a nice guy and that the people who have criticized me are a bunch of fools and bimbos.”

Randy was indeed a hell of a nice guy. At least to me. The rest is complicated.

———

Many thanks to everyone who makes Making Gay History, including story editor Inge De Taeye, associate producer Ali Lemer, audio engineer Katherine Cook, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. Special thanks to our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham, and our founding production partner Jenna Weiss-Berman. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Thank you to the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division for their assistance. And thank you to Con Edison for their generous support of our education work.

Season ten of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation; the Calamus Foundation; the Kipper Family Foundation; Christopher Street Financial; Mary Cadagin and Lee Wilson; Bryan, Christine, and Alex White; and scores of other individual supporters.

Head to makinggayhistory.com where you’ll find all our previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature.

And to keep up with what we’re doing, sign up for our newsletter on our website, and follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. And please keep those five-star iTunes ratings coming so more people can discover our proud history through the voices of the people who lived it.

I’m Eric Marcus. So long, until next time.

###