Pierre Seel

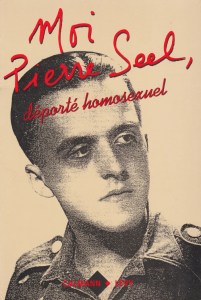

Undated photo of Pierre Seel from the cover of the first edition of his memoir "Moi, Pierre Seel, déporté homosexuel" ("I, Pierre Seel, Deported Homosexual"), written in collaboration with Jean Le Bitoux, © Calmann-Lévy, 1994.

Undated photo of Pierre Seel from the cover of the first edition of his memoir "Moi, Pierre Seel, déporté homosexuel" ("I, Pierre Seel, Deported Homosexual"), written in collaboration with Jean Le Bitoux, © Calmann-Lévy, 1994.Episode Notes

In 1939, French teenager Pierre Seel had his watch stolen at a cruising spot in his hometown. When he reported the crime to the police, he was placed on a list of suspected homosexuals. Two years later, with the city now under Nazi occupation, he was summoned by the Gestapo.

Episode first published February 20, 2025.

———

A note about language:

The person featured in this episode refers to Roma people by the now offensive term gypsies. To stay true to the original French testimony, we’ve not updated that term in our voiceover translation.

———

Audio Sources

- The first interview with Pierre Seel, conducted in 1993 by Daniel Mermet, is provided courtesy of Là-bas si j’y suis.

- The second interview with Pierre Seel, conducted by Laurent Aknin, is from the archive of the USC Shoah Foundation – The Institute for Visual History and Education, © 1996 USC Shoah Foundation. For more information about the USC Shoah Foundation, go here.

———

Resources

For general background information about events, people, places, and more related to the Nazi regime, WWII, and the Holocaust, consult the online Holocaust Encyclopedia of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM).

- Pierre Seel’s 1994 memoir I, Pierre Seel, Deported Homosexual: A Memoir of Nazi Terror (Basic Books, 2011).

- “The Life of Pierre Seel: Remembering the Forgotten LGBT+ Victims of the Holocaust,” a video presentation by Andrea Carlo (University of Wolverhampton/YouTube).

- Seel is featured in Paragraph 175, a 2000 documentary by Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman.

- At the time of his arrest, Seel was a so-called Zazou; learn more about the French anti-Nazi cultural youth movement in this libcom.org overview.

- This website by Arthur Koehl has information and resources about the Malgré-nous, men from the Alsace-Lorraine region who during WWII were forced to serve in the Reich Labor Service and the German armed forces against their will.

- In his telegram to the French president, Seel uses the phrase “Totgeschlagen, Totgeschwiegen” (“Beaten to Death, Silenced to Death”), which is taken from the first memorial dedicated to homosexual victims of the Nazi regime; it was unveiled in 1984 at the former Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria.

- This Schools Out article provides background on President Jacques Chirac’s 2005 acknowledgment of the deportation of French homosexuals during WWII.

- In 2019, Paris renamed a city street in Seel’s honor.

———

Episode Transcript

Pierre Seel VO: I was in awe of a uniform. To me, a man in uniform was handsome, and even at a very young age it stirred this desire in me that I couldn’t show, what with family, religion, sin, confession every week… So I was enveloped within this “security,” if you will, that, from the very start, prevented me from expressing my homosexuality.

———

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History: The Nazi Era.

Pierre Seel was born in 1923 in Alsace-Lorraine, a region in eastern France that had long been contested territory between France and Germany. He grew up in a middle-class Catholic family with four older brothers and an adopted younger sister in the town of Mulhouse, where his parents owned a large patisserie.

In 1993, Pierre was interviewed at his home in Toulouse by reporter Daniel Mermet for the French media outlet Là-Bas Si J’y Suis. His apartment is cluttered with papers, files, and newspapers. A candle burns in the kitchen. Pierre begins by telling Mermet about a fateful event that happened to him at a cruising spot in his hometown when he was 17.

———

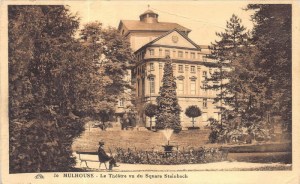

PS VO: There was a meeting place. It was a public restroom, an underground restroom near Steinbach Square in Mulhouse. And several of us boys would go down there and meet up. That’s it. And me, I just followed along. But it satisfied my curiosity and maybe my search for love, too.

And then something happened in this basement: somebody ripped off my watch, a wristwatch, one of my prized possessions. It had been a gift from one of my aunts who was my godmother. She lived in Paris. So to me, she was Paris. And the watch was Paris.

And he snatched it away from me. I yelled, “Stop, thief! Help!” Everyone else ran off, they vanished into thin air. I raced up the stairs by myself. But the thief had disappeared.

So there I stood, miserable. And then—I was so naive—I went down to the police station. I was shaking, and I said to the policeman on duty, “Someone’s just stolen my watch,” and we were going to prepare a statement.

An inspector—I knew him by sight, and he knew me—after all, I was the son of the family that ran one of the biggest pastry and confectionery shops in Mulhouse—he asked me, “What on earth were you doing in the restrooms? What are you doing? What if your Papa knew?”

I must have blushed up to my ears. Flushed all red. I said, “It’s a place to meet up.” “Ah,” he said. “Alright, you have to promise that you’re going to work hard, stop going down there. Promise me you won’t go there anymore—it’s dangerous, it’s dirty, et cetera—and we won’t tell your mom and dad.”

Well, thank you very much. And I left, free. And that was the year before the Nazis arrived in Mulhouse.

The Germans came in June 1940. They didn’t have much of a battle getting into Alsace. So we settled into this life with the Germans. First of all, we had to get rid of everything French. I stopped going to school and had to look for work. The textile shop next door was under German management—it had been a Jewish store but during the occupation it was run by Germans. So that’s where I got my start as a salesman. I remember my first sale, actually. It was a bra.

Nights were conducive to meetups. I had quite a few friends, some buddies, comrades who did a wide variety of things. Any scrap of freedom we could find. I wasn’t part of an actual resistance network. It was more a network of friends, a camaraderie of gay men. We would distribute anti-Nazi leaflets, for example. We would tear down posters, or put up others. I suppose that our friendship, our need for friendship, made it easy for us to band together.

One evening I came home from the store, and I went to kiss my mom, who was behind the cash register. And she said to me, “What did you do? You’ve been summoned to the Gestapo tomorrow.” That was it. That was in May of ’41.

I can still see the place. Everything. The screaming started right away. The shouting. Germans don’t know how to speak, they just shout and shout.

So there was shouting, but there were also screams. Those were from the victims. From the people who’d been arrested at the same time as me, who were summoned at the same time I was. They were already working on them. Working in quotation marks.

Daniel Mermet VO: Meaning that they tortured them.

PS VO: Exactly. There’s no other word for it. So I came through, and they sat me down at a table. It happened so fast. They showed me a piece of paper, that infamous report. We were right back at the catastrophe that had happened to me before the Nazis arrived. Did I recognize the report? What was I supposed to say? It had my signature on the bottom. Meet-up at Steinbach Square.

In any case, I’d immediately recognized the other boys. I had a boyfriend in the store where I worked. Jo and I, we were very happy loving each other. Jo had been summoned at the same time as me. There were twelve of us who’d been summoned that afternoon, twelve homosexuals. Twelve.

I don’t like to talk about how I was hit, how we were hit. And the torture… Some of us having to kneel on a ruler… Some of the torture was simple and some was more complex. Then slapping our faces. Always with the light, I can still see the bright lights they shined in our eyes. And then—they started with one of us—they made us drop our pants to make sure we weren’t hiding anything. Apparently you can hide papers or things in your anus, can’t you? We won’t mince words here.

And then it started. They went berserk, stark raving mad. It was truly hatred toward homosexuals, a hatred of us because we were homosexual. I got that right away.

DM VO: Did they know you had distributed leaflets and things like that?

PS VO: No, that’s just it, it never came out. It never came out. Personally, I wish it had, I wish they’d said, “You’ve taken posters down, distributed posters,” that kind of thing. Maybe then, at the time of the liberation in ’45, when I came back, I would have been proud and I would have talked about my resistance, said that I, too, was part of the resistance. No, they made us lower than the dirt underground because of our homosexuality.

DM VO: This was the torture session where you were sexually assaulted by the Nazis.

PS VO: Yes, that’s something I’ve never called attention to until now, I’ve always reserved the right to protect that memory. I’ve only been talking about the assault for a year or two now, because it’s too hard and because it still carries this sense of shame and degradation, you know.

Now, when I see the scene again, if I have to describe it in detail, the most terrible thing was maybe not the assault itself. It was the blood everywhere. On the papers, the tables. There was blood everywhere, like in a butcher’s shop. And the screaming, still—the Nazis shouting and our own cries, too, the cries of pain and suffering. Because you have people who can suffer in silence, who put their hand in their mouth to keep quiet, accept the suffering. And then there are others… Me, I screamed. I screamed as if my throat was being slit, but the more I screamed, the more it excited them, the more violent they became, the more they unleashed their violence. And there was nothing you could do. They were armed, first of all. They were wearing boots, and we were half naked. With blood everywhere.

The whole thing went on for a long time that afternoon, in different rooms. Always jostling and moving around. They’d come pull you from one room into another.

That evening my father and brother went to the Gestapo to ask about me. “Oh, your son’s a Schweinhund”—Schwein means “pig,” and Hund is “dog”—“and an Arschficker”—that means “ass-fucker.” My father almost fell over. My mom fainted when she found out. That’s how my parents learned I was gay.

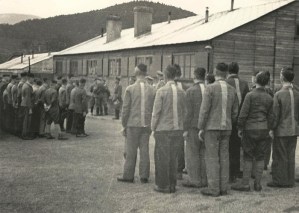

We were transferred to the Schirmeck-Vorbrück camp, in the Bas-Rhin. In ’41 it was beginning to fill up with communists, gypsies, Jews, and homosexuals like us. There were a lot of women, actually, prostitutes, and also criminals.

Coming into the camp was terrible. We were all shaved, and then sent to the showers and to change clothes. But for two or three days, I was made to walk around with a swastika on my head. I had very beautiful hair, I was a Zazou, as they used to say in those days, my hair all slicked back. But you know, the Nazis knew what they were doing. They’d come up with anything to denigrate you, to make you less than human. So with that swastika shaved into my hair, I was a laughing stock.

And on top of that, I had a badge that showed I was a homosexual. We didn’t have the pink triangle; we had a blue badge back then. So I didn’t have the star, or the red badge of the political prisoners, or the brown badge of the gypsies. We had our own badge, so everyone recognized us and some of our own compatriots made us the butt of their jokes.

We had roll call—Appell, they called it: every morning we had to go out to the main square of the camp. There were gallows there, too, for hangings. Sometimes they’d leave bodies out for days on end, with the crows circling. That was always there for us to see.

One morning, I didn’t see Jo. And then I saw him coming, flanked by two Gestapo officers. And then they read out a death sentence, in German of course. Everything I’m telling you about him… He was my boyfriend. My boyfriend, right? He wasn’t my lover, because it was all so very pure. It was wonderful what the two of us had together.

And there he was. They made him undress, strip down completely naked. They put a bucket, a tin bucket on his head, so you could only see his body. And then they set the camp dogs on him. I want this to be known, I want it to be said now, I want it repeated in every house everywhere, I want everyone to know that this is what the Germans did.

When Jo was being eaten by the dogs, they had music playing.

DM VO: What music?

PS VO: German classical music. Oh yes, that’s right. Some of it covered the screaming, but the screaming was already covered by the bucket on his head, right, that metal bucket. Except at times that made it louder, amplified it. This is an evil thing, what I’m telling you, yes? Now you understand why I have a candle burning at home.

DM: Mm-hmm.

PS: Eh?

DM VO: The memory of Jo.

PS VO: His life. And I’m 70 years old now, and the older I get, the more I need to think and feel. I think, and I hope, that his last thought was about me. Because I can’t stop myself from thinking about him. I can’t, I can’t do it. Ever.

So I was summoned by this man, the camp director, six months into my internment. Attention, “Heil Hitler,” all of that. That was a big deal, because I still considered myself a prisoner in the camp. So when he greeted me with “Heil Hitler,” I said, that’s it, I’m being released.

So he said, “I have your file here. We believe you are now worthy of being a German citizen of the Third Reich, a worthy citizen. You have worked hard and now you will leave to serve the fatherland.” He had me sign a paper that said I agreed not to divulge anything about what I had experienced in the camp, which explains why, afterwards, I kept my mouth shut and gagged, and I only confided in my mother.

It all went very quickly then. I had to go to the storeroom to pick up my things. Then, at the gate, I remember they came to meet me, my father, my mother, my brothers who were still at home. Not a single word was spoken, nothing was said. Just a welcome back kiss. And my father reached into his pocket and took out this little gold watch, he had a little Swiss watch, a Gousset. And he gave it to me without saying anything. It must have been awful for him, you know, to do that without saying anything.

———

EM Narration: After France surrendered to Germany in June 1940, the two countries negotiated an armistice that placed certain limits on the German occupation of France. But Alsace-Lorraine was de facto annexed by Nazi Germany and more than 100,000 men from the region were conscripted into the German armed forces. They were known as Malgré-nous—which means “in spite of ourselves”—French patriots who were made to serve the enemy against their will. In the summer of 1942, Pierre was forced to join their ranks, serving first in the Reich Labor Service and then in the German army, from which he deserted near the end of the war.

Pierre discussed what happened to him after his return to France in a 1996 interview with Laurent Aknin for the Shoah Foundation. By then, he’d published his memoir, I, Pierre Seel, Deported Homosexual—a rare account by a gay victim of Nazi persecution, made all the more remarkable by the courageous prominence of his real name in the title of the book.

Aknin asks Pierre if, after the war, he learned of any other gay men who’d been deported…

———

PS VO: No, because I didn’t try to find out, I kept quiet. I still felt ashamed of being gay. My mother was the only one who knew about my time in the concentration camp. And on and on, I didn’t say anything.

Then I was entirely focused on my mother’s health, she was very ill. In fact, she died in my arms. And then, I had to prepare for my wedding: I got engaged and married in Paris. Well, first the civil wedding in Mulhouse and then the religious wedding in Paris.

Laurent Aknin VO: And did your wife… Well, of course you didn’t say that you were gay, but did she know, for example, that you were conscripted into the German army? What did she know?

PS VO: Being enlisted in the Reich Labor Service, that wasn’t a secret. All Alsatians had gone through that. She also knew that I’d been deported. We’d even gone to visit the camp, I went with my children. They said, “ Dad, why were you arrested? What did they do to you? What did you do?” I didn’t give a reason.

Once I even had a huge argument with my wife—she was a courageous woman, she raised my children well. We were arguing about running out of money. And she said, “Don’t you get it, if you just had a pension… You aren’t even getting a camp survivor pension. Why won’t you fill out the application?” And I said “I won’t do it,” but I didn’t say why I wouldn’t do it. That fear that someone might find out the reason why I was deported, it was total agony, I suffered so much.

You see, I could have continued to live as a gay man. Instead, I said nothing. I hid my secret. I covered up my homosexuality. I respected my marriage contract for 28 years and it was hell. It was hell for me.

It’s an impossible life. It’s… demonic. You can’t, you cannot be both, it’s not possible. You can’t divide your heart between a woman and a boy, there’s no way.

LA VO: Uh, you also have a memoir which is important, it seems to me for—

PS VO: I sometimes regret having done the book, you know. I’ve regretted it because of the trouble it’s brought me. For example, in Toulouse, I was coming out of a doctor’s office, and a group of three young men and one young woman, well-dressed, well put together, respectable young people, they yelled, “Ah, look, the TV star!” They recognized me from my TV appearances. They came and they tortured me. They beat me, they pushed me to my knees. These were Nazi methods. In Toulouse, one year ago. My hat, the one I often wear, they put it on the ground and they made me kneel down and pick it up. And then I was beaten. They made me their plaything.

My marriage failed in the end, right, because of the book? The divorce is moving along. My wife doesn’t answer my calls anymore. My children still see me, maybe because I’ve been a good father. Maybe.

LA VO: But on the whole, are you glad you wrote it?

PS VO: No. No, because I cannot be satisfied as long as France—which is my country, after all, it is still my country—as long as France will not openly acknowledge the deportation of homosexuals. There must be an official speech where France, in the name of the President of the Republic, says that, yes, in Alsace Lorraine, there were French homosexuals who were deported. I wrote a telegram, actually, I’ll show you. Shall I read it to you?

LA: S’il vous plaît.

PS VO: Alright. I am Pierre Seel. My address again, 167 rue du Feretra, Apartment 85, 31400 Toulouse, France. Mr. President of the Republic, Élysée Palace, 75008 Paris.

Totgeschlagen, totgeschwiegen. Beaten to death, silenced to death. I am a surviving witness to the extermination of homosexuals and lesbians and I beg your forgiveness for still being alive.

I’m making them uncomfortable, I know. It’s uncomfortable for politicians, the existence of a man who throws tantrums, it makes people very, very uncomfortable. In the prison in Mulhouse, I was raped with a rod twenty-five centimeters long. And I said it on TV, but a journalist immediately cut me off. I should not have said that, it offended the good people of France.

Yes, so to come back to the telegram. I beg your forgiveness for still being alive. I think it only right to ensure that all of France is educated. My aim: to find out the truth, and see it through to the end. We know and we must know that silence is guilty. We must acknowledge all the victims of Nazism.

On several occasions, I have called for complete rehabilitation. I wish for respect, understanding, and official national recognition of the deportation for homosexuality. I am aware of the delicate nature of my request. Please accept, Mr. President, my deepest respect.

And I sent this telegram on September 8, 1996. Today is the 29th.

I have not received a reply yet, and I likely never will.

———

EM Narration: In 2005, nine years after Pierre sent his telegram, Jacques Chirac became the first French president to publicly acknowledge the deportation of French homosexuals during the Nazi occupation. Seven months later, Pierre Seel died in Toulouse at the age of 82. He was survived by his former wife, their three children, and Eric Feliu, his partner of 12 years. In Toulouse and Paris, two streets have since been renamed in his honor.

———

In our next episode, Dutch musician and underground activist Frieda Belinfante risks her life in a plot to thwart the Nazis’ murderous plans.

———

This episode was produced by Inge De Taeye, Nahanni Rous, and me, Eric Marcus. Our audio mixer was Anne Pope. The English voice over was provided by Arnie Burton, the translation by Allison Charette and Inge De Taeye. Our studio engineer was Michael Bognar at CDM Sound Studios. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Thank you to our photo editor Michael Green, our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham, and our founding production partner, Jenna Weiss-Berman at Pineapple Street Studios.

Many thanks to Là-Bas Si J’y Suis for the recording of the 1993 interview with Pierre Seel. Seel’s 1996 interview is from the archive of the USC Shoah Foundation—The Institute for Visual History and Education.

To learn more about the people and stories featured in our episodes, please visit makinggayhistory.org, where you’ll find links to additional information and archival photos, as well as full transcripts.

This special series on the experiences of LGBTQ people during the rise of the Nazi regime, World War II, and the Holocaust is a production of Making Gay History, in partnership with the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale University.

I’m Eric Marcus. Until next time.

###