Overview Part II

Prisoners in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, Germany, December 1938. Before the war, the Sachsenhausen inmate population consisted primarily of German anti-Nazi dissidents, communists, homosexuals, Jehovah's Witnesses, and pacifists. Credit: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Prisoners in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, Germany, December 1938. Before the war, the Sachsenhausen inmate population consisted primarily of German anti-Nazi dissidents, communists, homosexuals, Jehovah's Witnesses, and pacifists. Credit: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.Episode Notes

In our second introductory episode, we focus on life in the Nazi concentration camps and offer a glimpse into the experiences of LGBTQ people in occupied countries during WWII as we continue to set the context for the eight profile episodes to follow.

———

A note about the episode image:

This 1938 photo of Sachsenhausen prisoners is often used to illustrate the Nazi persecution of homosexuals, but as historian Joanna Ostrowska has noted, it is in fact uncertain whether the inmates shown were pink triangle prisoners. For information on the men in the photo and the context in which it was taken, read this excerpt from Dr. Ostrowska’s 2021 book Oni: Homoseksualiści w czasie II wojny światowej (Them: Homosexuals During World War II).

———

Audio Sources and Excerpted Writings

-The following interview segments are from the archive of the USC Shoah Foundation – The Institute for Visual History and Education:

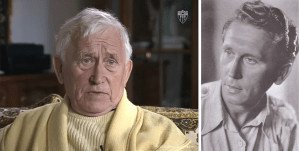

- Walter Schwarze, © 1997 USC Shoah Foundation

- Kitty Fischer, © 1995 USC Shoah Foundation

For more information about the USC Shoah Foundation, go here.

-The Leo Classen excerpt is taken from “Die Dornenkrone: Ein Tatsachenbericht aus der Strafkompanie Sachsenhausen” (“The Crown of Thorns: A Factual Report from the Sachsenhausen Penal Company”), Humanitas: Monatsschrift für Menschlichkeit und Kultur 2, no. 2 (1954): 59-60.

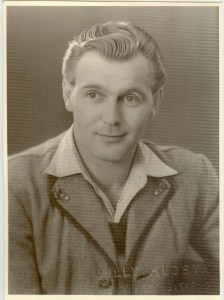

-Audio of the 1990 interview with Josef Kohout used by permission of QWIEN, the Center for Queer History in Vienna.

-The Josef Kohout book excerpts are from Heinz Heger’s The Men with the Pink Triangle, Haymarket Books, Chicago, 2023. Used by permission of the publisher. Original German edition Die Männer mit dem rosa Winkel © 1972/2014 MERLIN VERLAG Andreas Meyer Verlags GmbH. & Co. KG, Gifkendorf, Germany. English translation by David Fernbach © 2004 MERLIN VERLAG Andreas Meyer Verlags GmbH. & Co. KG, Gifkendorf, Germany.

-The following interview segments are courtesy of the Jeff and Toby Herr Oral History Archive, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C.:

- RG-50.578.0001, oral history interview with Gerald B. Rosenstein

- RG-50.030.0270, oral history interview with Rose Szywic Warner

- RG-50.030.0037, oral history interview with Tiemon Hofman

For more information about the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, go here.

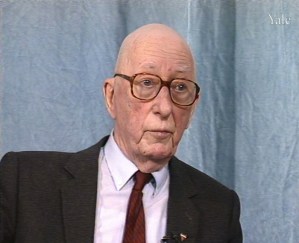

-Arthur Haulot audio courtesy of the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies, Yale University Library.

-The Ovida Delect excerpt is from her memoir La vocation d’être femme (The Vocation to Be a Woman). Copyright © Éditions L’Harmattan, 1996. Used by permission of Éditions L’Harmattan.

-The Ruth Maier excerpts are from Ruth Maier’s Diary by Ruth Maier. Copyright © Gyldendal Norsk Forlag AS, 2007. English translation copyright © Jamie Bulloch, 2009. Used by permission of The Random House Group Limited.

———

Resources

For general information about the Nazi persecution of LGBTQ people, see the episode notes of our first overview episode. To learn more about some of the topics and people discussed in this episode, explore the links below. (Some of the websites linked below are in foreign languages, but internet browsers like Chrome allow you to access them in English translation.)

- Walter Schwarze’s camp internment came to an end in the spring of 1944 when he was released to join the Wehrmacht. A year later, while fleeing west with his unit, he was captured by Soviet troops and spent the next four years in prison camps. He married soon after his return to Germany. The marriage ended in divorce, as did a second marriage. If you speak German, you can watch his entire testimony on the USC Shoah Foundation website here (registration for their Visual History Archive is free).

- The full text of Leo Classen’s concentration camp testimony in Humanitas has been published only in Spanish translation. This Gayles.tv article includes a few brief excerpts, which can be accessed in English.

- Learn more about Danish doctor Carl Værnet’s experiments on homosexuals at Buchenwald as well as his post-war life in “The Nazi Doctor Who Experimented on Gay People—and Britain Helped to Escape Justice” by Peter Tatchell (Guardian, May 5, 2015).

- One concentration camp inmate known to have submitted to so-called “voluntary” castration is Ernst Pack; learn more about him in this biographical overview from the Pink Triangle Legacies Project (PTLP).

- Read about Josef Kohout’s time in Sachensenhausen and Flossenbürg in the seminal 1972 book The Men with the Pink Triangle (Haymarket Books, 2023). It was published under the name Heinz Heger—a pseudonym for Hans Neumann, a friend of Kohout’s. It was the first widely published account of the experiences of a gay concentration camp survivor. Read a biographical overview of Kohout’s life on this webpage of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), which houses his wartime papers and the pink triangle badge he was forced to wear. In this video, Klaus Müller discusses the historic collection.

- Watch this video of Jewish survivor Kitty Fischer in which she talks about the gay man she encountered in Auschwitz who went on to save her life (USC Shoah Foundation/YouTube).

- For more on sexual coercion and pipels in the camps, read “Sexual Violence Against Men and Boys During the Holocaust: A Genealogy of (Not-So-Silent) Silence” by Dorota Glowacka (German History, Vol. 39, No. 1, March 2021).

- Gerald Rosenstein’s entire testimony can be viewed on the USHMM website. Read his Legacy.com obituary here.

- Learn more about Henny Schermann in this PTLP bio and about Mary Pünjer in this Hamburg Stolpersteine entry by Astrid Louven. For an additional example of how women’s sexual orientation determined their fate under the Nazi regime, read this Berlin Stolpersteine entry by Claudia Schoppmann about Elli Smula. She and her colleague Margarete Rosenberg were both sent to the Ravensbrück concentration camp as political prisoners, but their camp records explicitly identified them as “lesbian.”

- Eve Adams, another lesbian victim of the Nazi regime, is not featured in our series, but her story merits exploring. In the 1920s, as a Polish immigrant to the U.S., she ran a gay and lesbian tearoom in New York City and published Lesbian Love—“the earliest portrait of the lesbian community released in the United States by a lesbian author,” according to her biographer Jonathan Ned Katz. Legal problems got her expelled from the U.S. In 1943, she was arrested in France as a “foreign Jew” and murdered in Auschwitz. Learn more about her in this brief PTLP profile or in Katz’s book The Daring Life and Dangerous Times of Eve Adams (Chicago Review Press, 2021).

- For more on homophobia in the camps and in survivor testimonies, and the erasure of queer stories from Holocaust history, read “Queer History and the Holocaust” (On History, March 4, 2019) and “Why We Need a Queer History of the Holocaust” (History Workshop, February 19, 2020), both by Anna Hájková.

- In Ravensbrück, the Reich’s largest concentration camp for women, several relationships were forged that long outlasted the war. One of them, between Nelly Mousset-Vos and Nadine Hwang, was featured in the 2022 documentary Nelly & Nadine by Magnus Gertten.

- Ovida Delect was the subject of Appelez-Moi Madame (Call Me Madame), a 1986 documentary by Françoise Romand; watch the trailer here. (Subtitled DVDs of the film are available here. For French readers, Delect’s memoir La vocation d’être femme (The Vocation to Be a Woman) is available here (Éditions L’Harmattan, 1996). In 2019, Paris renamed a city square in Delect’s honor.

- Tiemon Hofman’s entire testimony is available on the USHMM website. It’s in Dutch, but you can find out more about him in the English interview summary and the time-coded notes on that same webpage.

- To read Ruth Maier’s Diary, go here (Harvill Secker/Random House, 2009). For more on Maier’s relationship with Gunvor Hofmo, read “The ‘Twin Souls’ Ruth Maier and Gunvor Hofmo” by Raimund Wolfert (Arolsen Archives).

———

Episode Transcript

Walter Schwarze VO: We had to stand, stand, stand all day long in the same spot. Our abdomens hurt so much. A bucket was passed around for our bodily needs.

———

Eric Marcus Narration: Walter Schwarze was a German postal service worker from Leipzig. When he was 25 years old, he was denounced for criticizing the war. Then, the Gestapo searched his home. They found letters from Hans, his longtime lover. Schwarze was taken to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp near Berlin.

———

WS VO: The winter of 1940–41 was grimly cold. Our pockets were sewn shut, we didn’t have gloves. On our feet, we only had rags and wooden shoes. Above us, the crows from the pine forests smelled the dead. When the smoke from the crematorium started to rise, you just kept thinking, when will it be my turn?

———

EM Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History: The Nazi Era.

During the Nazis’ reign, a hundred thousand German men were arrested under the antigay law Paragraph 175. More than half were convicted, and most were sent to regular prisons. But between seven and ten thousand gay men, like Walter Schwarze, were sent to concentration camps—camps that were ruthlessly administered by the SS, the Nazis’ notorious paramilitary organisation.

In this episode: life in the concentration camps. And later, a glimpse into the experiences of LGBTQ people in Nazi-occupied countries during the war.

The earliest known account by a concentration camp survivor who was persecuted for his homosexuality comes from Leo Classen, a gay German doctor. Classen was in his early 30s when he was imprisoned by the Nazis in Sachsenhausen, the same concentration camp as Walter Schwarze. In the mid-1950s, he chronicled his experiences in Humanitas, a West German homophile magazine.

———

Leo Classen VO: Ours was a barracks like the others, only this one was isolated, surrounded by a high wooden fence. Above the entrance to the barracks a colorful sign was put up to complete the measure of mockery. On it was written: “WELCOME!”

———

EM Narration: Classen then describes the lethal conditions of the brick factory where homosexuals were forced to work in the clay pit—or, as it was known among prisoners, the “death pit.”

———

LC VO: The suffering that now began for us was immeasurable and unimaginable. I cannot recall any other instance of human savagery in the history of mankind that has left such terrible traces of blood and tears as this: Klinker—the brick factory!

Within two months of this work detail, our penal company had shrunk to a third of its people.

Killed! Shot! Hanged! Drowned! Starved to death!

“Shooting those trying to escape” was a profitable daily game for the guards. For each headshot they were given five marks and three days’ special leave. Some managed several hits a day.

There were also two jackals in human form among us who were our kapos. They were the henchmen of death and enjoyed themselves, gleefully growing a fat stomach at the expense of the dying.

Bread and death, those were the two pillars of our existence. We had nothing else we could hold on to. Anything beyond that and what we once called life was far, far away, and nothing but the smell of blood and decay, of torment and meanness, surrounded us here, and we dragged ourselves from one gray morning to the next under a crown of thorns with rattling bones, and never again did it get light.

One morning, when I had reached a body weight of 86 pounds, a guard said, “Well, have you made up your mind yet? Do you want to cross over? I’m a perfect shot and it doesn’t hurt either, so come on! Just one step over the guard line and you’re saved!”

———

EM Narration: Homosexuals as a group were not slated for total annihilation by the Nazis like Jews and Roma and Sinti. The official view was that what needed eradicating was the homosexual lifestyle. By the Nazis twisted logic, if the “Aryan” homosexual male could be made to give up his degenerate ways, there was still a place for him in the racially unified community of the German people. But in reality, the savagery of the Nazis’ methods to cure or reeducate these men often proved lethal. Thousands of gay men died in the camps, usually during the first year of their incarceration.

The so-called 175ers died as many other prisoners did: from forced labor, inadequate rations, disease, and injury—often as a result of torture—from suicide, or the homicidal whims of the SS. But the SS often assigned them to even harder work details and gave them even less food, believing that it would toughen them up and make them more manly. It was the kind of conversion therapy that for many ended in death.

Other efforts to stamp out homosexuality included forcing 175ers to have sex with female prisoners who had been condemned to work the camp brothels.

Danish doctor Carl Værnet claimed he could cure gay men by implanting an artificial gland under their skin that released testosterone. Under Nazi leader Heinrich Himmler’s direction, a dozen prisoners at Buchenwald were subjected to the experiment. Two died. We don’t know the fates of the other ten.

A more common attempt at curing men of their homosexuality involved coercing prisoners to submit to so-called voluntary sterilization or castration.

Josef Kohout was a Viennese man who spent nearly five and a half years in concentration camps because of his homosexuality. In a 1990 interview, he described how an SS officer in Flossenbürg put pressure on him to get castrated.

———

Josef Kohout VO: He was a Sturmbannführer. And he called me in a few times, and it came up that homosexuals should be castrated. And I went in to see him, and he said to me, “Well, you gay pig, haven’t you gotten yourself castrated yet?” I said, “No, and I’m not going to have it done either. I’ll come out the same way I came in.”

———

EM Narration: Once the Nazis standardized their prisoner classification system across concentration camps, most of the 175ers were forced to wear an inverted pink triangle badge on their camp uniform.

The pink triangle may later have been reclaimed as a symbol of LGBTQ resistance and pride, but in the camps, it was a magnet for the scorn and hatred of the SS. In a system that was violent and dehumanizing for all inmates, there were special indignities reserved for prisoners with the pink triangle.

In camps like Sachsenhausen, for example, pink triangle prisoners were isolated and subjected to inhumane scrutiny. Josef Kohout gave an account of this treatment in Heinz Heger’s 1972 book The Men with the Pink Triangle.

———

Josef Kohout VO: Our block was occupied only by homosexuals. We could only sleep in our nightshirts, and had to keep our hands outside the blankets: “You queer assholes aren’t going to start jerking off here!” The windows had a centimeter of ice on them. Anyone found with his underclothes on in bed or his hands under his blanket—there were checks almost every night—was taken outside and had several bowls of water poured over him before being left standing outside for a good hour. Only a few people survived this treatment. The least result was bronchitis, and it was rare for any gay person taken into the sick bay to come out alive. We who wore the pink triangle were prioritized for medical experiments, and these generally ended in death. For my part, therefore, I took every care I could not to offend against the regulations.

———

EM Narration: SS officers also took pleasure in devising creative ways to degrade pink triangle prisoners. In the Auschwitz concentration camp, Jewish survivor Kitty Fischer witnessed the depths of humiliation gay men had to endure when one day in 1944, she was caught in a humiliating situation herself.

———

Kitty Fischer: A latrine is a long row of holes in the ground, one against the other. That’s what latrines are. They were full of muck and shit and vomit, and I thought, I am not sitting in this dreck when my mother taught me you never sit on other people’s toilet. And I crouched, and they caught me from the back with a stick, and I had a terrible pain and I fell into the latrine. So I was full of shit, no paper, no underwear, stark naked.

And suddenly I saw striped trousers walking towards me and big wooden clogs. And it was a man, and I looked for the Star of David, and he had a big pink triangle, and the number, and he carried a bucket, and he carried a brush. And he said, in a very beautiful German, not in Yiddish, “Hurry, hurry, get up, I have work to do.”

I said, “I can’t. I am so ashamed. What is this?” And I looked at this pink triangle. And he said to me, “I’m gay. Ich bin schwul.” What did I know what schwul was. I said, “Is that a religion?” He said, “No, I’m a homosexual.” So I still didn’t know.

And he explained to me that with his partner, he lived in Munich and the, the Gestapo, under Paragraph 175, which was for perversion, broke into the flat. The partner went to Dachau. He came to Auschwitz in 1940—four years before I met him—and a German, a non-Jew. And because he was not a Jew, they asked him sarcastically when they shaved him and put on the pajama, “What is your profession?” He said, I’m an academic portrait painter from Munich.

“We have just the right thing for you.” And they took him to a laundry and gave him a bucket with whitewash and a brush. And since 1940, seven days a week, 10 hours a day, he had to brush the shit off the latrine so that he shouldn’t come out of experience with his brush.

And that’s what Germans did to Germans.

———

EM Narration: Pink triangle prisoners weren’t just scorned by the SS, but also by their fellow inmates, who upheld a blatant double standard when it came to same-sex behavior. As Josef Kohout noted, they reviled the 175ers as “filthy queers,” but they took a far more tolerant view of inmates from different prisoner groups who coerced more vulnerable men into sex. They were seen as straight men who engaged in homosexual behavior only because they didn’t have access to women to satisfy their “natural” urges.

Sexual coercion—and often violence—was rife in the camps. The SS created a hierarchy that put prisoners in charge of other prisoners in exchange for privileges like better food and accommodations, and lighter work. Kapos, for example, supervised the labor details; block elders oversaw the barracks.

Pink triangle inmates almost never got these jobs. Most often, it was the green triangle prisoners, the criminals, who were elevated to the rank of kapo or block elder.

Many took advantage of their position of power to take a young lover—or a pipel, as they were often called. These prisoners, typically young teenagers, received privileges in turn: better rations, less strenuous work assignments, and protection.

Gerald Rosenstein, a gay German Jew, was deported from the Netherlands with his family in 1940. They were taken to Auschwitz where men and women were immediately separated from each other. He and his father were assigned to the men’s barracks.

———

Gerald Rosenstein: The kapo and the sub-kapo had a room at the beginning of the barracks, separated from the rest of the barracks—a private room with running water. And the kapo had all of us lined up and he went through the line and he picked me out. He said, “I need somebody to clean the cabin for me.”

And whether he was gay or not, I don’t know, but certainly not, no woman being present, I was picked out as a sex, sexual object for him. And I played completely dumb. Uh, I would not have played dumb if it hadn’t been for peer pressure that my father was outside waiting for me, knowing what was going on. That all the other people we were, were with from Holland knew why I was picked out to go in there.

And, uh, my smarts turned on. I could have easily been seduced by a sardine sandwich, which was offered to me, and chocolate, which was offered to me, and I said no. And then he pointed to a big jar of Vaseline standing there—that’s, you know, what that is for. And I said, uh, “Ich weiß das nicht.” So, “I don’t know about that.” Anyway, he got tired of my stupidity and my non-cooperation and sent me back outside, which was a very good thing, uh, because if I had acquiesced, and, uh, if he would’ve grown tired of me, I would’ve just been sent to the gas chamber and he would’ve picked up another boy.

As it is, he went outside and picked himself another boy who was perhaps more cooperative. And, uh, I was led off the hook. And believe me, it was, uh, uh, an early experience in prison smarts, so to say. You know, today we, there’s an expression in the prison lingo, you know, “I would’ve been his bitch,” you know, but a bitch of a 40-year-old man, uh, a 15-year-old or 16-year-old boy. And, and the social shame attached to it, even in Auschwitz-Birkenau, uh, I could not overcome.

———

EM Narration: Few young men who caught the eye of a kapo managed to extricate themselves the way that Rosenstein did; many were “recruited” by force. But his predicament sums up the dangers and temptations of being a pipel: on the one hand, the promise of extra food when most people were starving; on the other, the dread and revulsion of being at the mercy of a criminal more than twice his age. And the fear of being ostracized by his fellow inmates. Because there was little sympathy in the camps for a pipel, or for any prisoner seen to benefit from sexual barter, even when their survival depended on it.

Suspected lesbians who ended up in the concentration camps did not have their own identifying badge. There was no specific law that criminalized lesbian behavior, so they were grouped according to the primary reason for their arrest—racial, criminal, political, or social. Most often, they ended up being assigned the red triangle of political prisoners or the black triangle of “asocials.” That was a catchall category for Roma and Sinti as well as nonconformists, alcoholics, vagrants, and other people the Nazis considered social deviants.

But that didn’t mean women’s sexuality, or perceived sexuality, didn’t affect their fate. In 1941 Dr. Friedrich Mennecke, a eugenics proponent, was tasked with selecting victims for a euthanasia campaign designed to rid concentration camps of people who were unable to work—people the Nazis referred to as “ballast.” He was also authorized to select able-bodied Jews he considered undesirable for other reasons.

Among the Jewish women Mennecke singled out at the Ravensbrück concentration camp were Henny Schermann and Mary Pünjer. Schermann, he noted, was a “licentious lesbian.” His summary of Pünjer’s case read: “Married full Jewess. Very active (‘saucy’) lesbian. Constantly frequented lesbian bars and exchanged intimacies in the bar.” In the spring of 1942, Schermann and Pünjer were gassed by carbon monoxide.

Homophobia in the camps didn’t just extend to 175ers. In survivor testimonies recorded after the war, lesbians or women suspected of engaging in same-sex behavior are generally described with contempt, too—or with befuddled judgment, as in this clip from a Jewish camp survivor from Poland.

———

Randy M. Goldman: Because of the unusual circumstances, do you think that any of the women in your block had sexual relationships with each other? Was that anything you saw?

Rose Szywic Warner: Eh, I didn’t saw. I saw lesbians. I hear lesbians doing it and we didn’t know what lesbian is. And I said, “What are they doing there?” So they said, “Don’t you know? They make love.” And I said, “What love? I don’t know a woman with a woman.” And they said they lesbians. So, because it was a lot of German lesbians, too, you know. But they were Czechoslovakian and, and they lived on top of me and I hear them.

———

EM Narration: As far as this survivor was concerned, lesbian activity was something only women from other countries engaged in—the Germans and Czechoslovakians, not her fellow Poles.

But in the camps, where people’s physical and spiritual survival hung by a thread, queer experiences were more prevalent and meaningful than most survivor testimonies acknowledge. Arthur Haulot, a Belgian socialist resistance fighter who survived the Mauthausen and Dachau concentration camps, provided a rare nonjudgmental insight into this.

———

Arthur Haulot VO: I didn’t engage in homosexual activity, but I was on the verge. Yes, of course. Why? Because it’s the most natural thing in the world. First of all, there are no women. Second, there’s not only the physical need—that’s not the only thing that comes into play—but the need for comfort, the need for friendship, the need for human warmth. Yes, of course. That brought me to the verge of homosexuality. We caught ourselves, my friend and I, laughing, and that’s as far as it went. But I understood perfectly, going through it myself and coming so close, well, I understood why for others, it went much further.

That’s what you have to realize. The concentration camp, with a few exceptions, was a place where you were put for the rest of your days. There was no reason to think you’d ever get out alive.

———

EM Narration: Many inmates, regardless of their sexual orientation, sought relief from the everyday despair through affection or sexual intimacy with others.

For Ovida Delect, it was her sense of self and her imagination that carried her through. Delect was a French resistance fighter assigned male at birth. She didn’t start to live her life as a woman until the early 1980s. But while she was incarcerated at the Neuengamme concentration camp as a political prisoner, it was her innate understanding of herself as a woman that served as a beacon. In her memoir, she wrote about retreating into a dream world to reanimate that “pearl” of femininity inside of her.

———

Ovida Delect VO: As for me, I’m convinced that what saved me is my feminine essence.

After working for 14 or 15 hours; walking or running back and forth between the camp and the worksite; roll calls upon roll calls; endlessly waiting in fog or rain squall or snowstorm, or under a scorching sun; after lining up for soup; and a thousand other hellish things, I’d come back to my block with my head done in from the yelling, my eyes full of sneering images, my body often black and blue.

I was in a state of shock or severe agitation.

I’d bury my head in my coarse, filthy sleeves and try to “recover.”

It wasn’t always easy, but I’d manage to “seal my shell” from breaths and drafts, noisy coughs and shouts, my neighbors’ bony limbs and sharp elbows, murky smells, and above all, the whole hellish atmosphere of our day-to-day life. This way I would give this “pearl” a new lease on life, a frail rebirth in which its little flame could sputter brighter, then brighter.

I would pull on skirts, in wide expanses of freedom and fleetingness, in protective forests, meadows dotted with daisies and primroses, houses that were so very warm.

I would be a hostess, an assistant, a fiancée, a little bride, a ballerina, a fashion model for stunning long dresses, a nurse, a mother, a schoolteacher, a poetess, a musician, a healer. I would dance in velvety muslin, elusive taffeta, layers of quivering gauze. I would swish against eddies of satin and caresses of tulle. I would be a caryatid of silk in motion. Nothing was too beautiful.

And my reality wasn’t snuffed out. It was kindled, in fact, by contradiction.

I made a woman

With my pain

With my soul

And I dreamed…

… I did more than dream. My pain and my soul, they were my real life.

So I prevailed over the pervasive death. Not only life being ended but also being reduced to base instinct, stagnation, hopeless apathy.

Femininity was not only an oasis, a wellspring, a rediscovery for me of depths; it was also my way up and out—beyond the watchtowers, into the blue and its stars.

And it was a sheltered space that made the company of others feel possible again.

———

EM Narration: Most pink triangle prisoners in the camps were German men or men who were considered German—like the Austrians whose homeland had been annexed by the Nazis in 1938. In general, no one else wore the pink triangle. After all, homosexuality was viewed primarily as a threat to the strength and growth of the German national community.

That preoccupation was also reflected in the Nazis’ policies toward homosexuals in countries they occupied during the war. In Poland, for example, gay men were at risk if they seduced German men, but sex among Polish men was not the Nazis’ concern. As a 1942 Gestapo memorandum stated: “It is not necessary to bring to court Poles who […] have sexual intercourse with Polish men. Rather, they must be evicted and transported to an area where their activities present no danger to Germandom.”

The Poles would never join the Germandom. Their Slavic blood was considered inferior and once the war was won by the Nazis, Poland was to become a slave state. The Dutch, with their superior Nordic blood, were considered worthy of becoming an integral part of a future greater Germany, and shortly after the Nazis invaded the Netherlands, they introduced a law modeled on Par. 175.

Tiemon Hofman was a teenager when he was arrested in a hotel with an older man in the occupied Netherlands in 1941.

———

Tiemon Hofman VO: Suddenly there was a loud banging on the door. It turned out to be the hotel owner and he said, “Open up or I’ll kick the door in.” And that’s what he did. The door immediately flew off its hinges, and there we were, with our clothes still in some disarray. The hotel owner said, “I see how it is, we’ve got ourselves a couple of faggots here. I’m kicking you downstairs and I’m turning you over to the police.” He kept on ranting and raving, and that’s how we were hustled down the stairs to the taproom.

In the taproom, there was a table with about eight, ten, maybe twelve Germans. And the hotel owner said something in German that I didn’t quite understand. The Germans stood up, took their rifles, attached bayonets to them, and just like that we were surrounded. I couldn’t move in any direction and of course I was terrified. Terrified. All I heard was that the hotel owner said, “They are Schwulen.” Faggots.

Then two police officers arrived and one of them handcuffed me to him. He said, “If you try to draw attention outside or start a commotion or shout,” he said, “look, this is a revolver.” He showed the revolver, put it in his pocket, and kept pressing it up against my leg. He said, “I’ll shoot you. I’m allowed to do that by the Germans, because the Germans hate everything faggot. So it’s your call: either you come along quietly, or I shoot you.”

———

EM Narration: While Hofman was in custody, Dutch police officers beat him, tortured him, and confiscated his notebook. It contained the names of other gay men in his circle.

———

TH VO: I think it was on the third day after my arrest that they said I would have to identify my friends. And one of the police officers said, “Yeah, and two of those bastards you won’t see again, because one of them has already taken the coward’s way out and hanged himself in his cell.” That was Willy Bakker, a very nice guy, I think he was about 22, 23 years old, no more. And they said a hairdresser, a certain Leo, had gassed himself. They said it in a tone… laughing. They gloated over it.

So I had to walk past my friends—friends, acquaintances—and it was terrible, just terrible. They were lined up, side by side—six or seven men in a row. There were no other civilians among them. It was just them lined up. They didn’t have glass back then through which you could identify someone; you had to walk past them. And one by one, when the officers said, “Who’s this?” I had to give their name.

I walked past them, mostly with my head down because I was ashamed. I was ashamed, and I kept thinking, I’ve betrayed you. Of course that wasn’t the case, but they were in that stupid notebook. That was the great misery. So I walked with my head down and every once in a while I briefly raised my eyes. Then I saw who it was, and I said, “Yes, that’s so-and-so and that’s so-and-so, and that’s so-and-so.” That confrontation, it was awful, just awful.

———

EM Narration: Hofman was sixteen at the time. When he was temporarily released after that harrowing lineup, his mother picked him up at the police station. She gave him several beatings. And then she locked him in his room. When he was later ordered to appear in court, he went by himself. No one was there to support him. He was convicted and sent to prison for seven months, then spent two years in reform schools before he was finally allowed to return home.

Hofman was particularly unlucky. Few Dutch homosexuals were arrested; enforcement of the Dutch antigay law was left to the local police and was generally lax.

At the time of Hofman’s 1941 arrest, the Nazis’ priority lay elsewhere: the annihilation of Europe’s Jews.

By the time war broke out in 1939, approximately 400,000 Jews had left Germany and Austria, whose annexation exposed Austrian Jews to the same antisemitic restrictions, harassment, and state-sanctioned violence that Jews in Germany experienced. Many emigrants found refuge in the U.S., Palestine, Great Britain, Central and South America, and Shanghai. But nearly 100,000 fled to other countries in Europe that were subsequently conquered by the Nazis. That’s what happened to Austrian teenager Ruth Maier, who witnessed the Nazis’ takeover of her country.

———

Ruth Maier VO: Diary entry for Wednesday, October 5, 1938, Vienna. It’s early, nobody on the streets. A Jewish man, young, well-dressed, comes round the corner. Two SS men appear. Both of them hit the Jew, he staggers … holds up his head, moves on.

I, Ruth Maier, 18 years old, now pose the following question as a human being. As a human being I ask the world whether it should be like this … I ask why it is allowed, why a German is permitted to hit a Jew for the simple reason that he is a German and the other man a Jew!

———

EM Narration: The writing was on the wall, and like many of their German neighbors, Austrian Jews who had the resources and connections to leave, did. Maier’s mother, grandmother, and sister got visas for the UK, and in early 1939 Maier herself made it to Norway.

But in June 1940, Norway fell to Germany. As Maier’s hopes of being reunited with her family faded, she found comfort with Gunvor Hofmo, a woman she’d met in Norway’s volunteer Women’s Labor Service. And she experienced their relationship with all the intensity of a great young love.

———

RM VO: January 9, 1941. The days are longer when you love somebody. When Gunvor is not there, something in me is missing. It is not until she reappears, far away in my field of vision, that I can let out a sigh of relief: she’s back.

September 22, 1941. Autumn has suddenly arrived as if overnight. Last week we were astonished as the trees were still green and the evenings still light. Now we’re just as astonished because the leaves have turned totally yellow as if overnight. … The nights are now dark, and at night-time I cannot see Gunvor when she lies beside me like a small child. In spring and summer I saw her eyes watch me at night, so deep, so inscrutable, often so unutterably sad, too. Now I can only feel her mouth and her soft skin, and hear her say, “It’s so wonderful to have you lying beside me. … So secure.”

November 22, 1941. Concerning loneliness. I’m no longer lonely. I have Gunvor. I’ve staked everything on her. And yet sometimes I long for a man. Without Gunvor I’d never be able to cope without a man. So this man-less-ness is just a gentle pain inside me.

———

EM Narration: In November 1942, Maier was rounded up for deportation. She wrote a final note to Hofmo that was smuggled out of the ship that would carry her to mainland Europe.

———

RM VO: I think it’s just as well that it happened this way. Why shouldn’t we suffer when there’s so much suffering? Don’t worry about me. Perhaps I wouldn’t even change places with you.

———

EM Narration: Maier and 531 other Jews were sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp. Women, children, and those who couldn’t work went directly to the gas chambers on arrival and were killed.

Gunvor Hofmo went on to become a celebrated poet in her native Norway, and lived openly as a lesbian in a long-term relationship. How Maier herself would have identified or how she would have lived her life had she survived the war, we’ll never know. But thanks to Hofmo, who saved Maier’s diary and letters, we do know how Maier experienced her first true love during an all too short life.

This is how we’re left to piece together the experiences of LGBTQ people during the Nazi era: through all-too-rare written accounts, through traces of queer lives in Nazi archives, and through the few recorded testimonies from those who survived. In the eight episodes to come, you’ll hear from people who shared their recollections, often in the face of stigma and shame, and made an invaluable contribution to our understanding of the lives that LGBTQ people lived during this incredibly dark chapter of history.

———

Up next, our first profile episode takes us to Poland, where 16-year-old Stefan Kosinski falls in love with a Nazi soldier.

———

This episode was produced by Inge De Taeye, Nahanni Rous, and me, Eric Marcus. It was mixed and sound designed by Anne Pope. We had voiceovers by Arnie Burton, Claybourne Elder, John Cariani, Bianca Leigh, and Rachel Botchan.

Our studio engineers were Michael Bognar, Katherine Cook, and Charles de Montebello at CDM Sound Studios. Our music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Thank you to our photo editor Michael Green, our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham, and our founding production partner, Jenna Weiss-Berman at Pineapple Street Studios.

The segments of the Walter Schwarze and Kitty Fischer interviews are from the archive of the USC Shoah Foundation—The Institute for Visual History and Education. The oral history excerpts of Gerald Rosenstein, Rose Szywic Warner, and Tiemon Hofman are from the Jeff and Toby Herr Oral History Archive at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. Thank you to QWIEN, the Center for Queer History in Vienna, for the recording of the 1990 interview with Josef Kohout. The Arthur Haulot excerpt was provided courtesy of the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale University.

Many thanks to Haymarket Books for their permission to excerpt Heinz Heger’s The Men with the Pink Triangle. The excerpts from Ruth Maier’s Diary: A Young Girl’s Life Under Nazism were included by permission of Gyldendal Norsk Forlag and the Random House Group Limited.

Many thanks to Benoît Loiseau for providing us with research on Ovida Delect, to Editions l’Harmattan for letting us use an excerpt from her memoir La vocation d’être femme, and to translator Jeffrey Zuckerman. Thank you also to Raimund Wolfert at the Magnus Hirschfeld Society for providing us with a copy of Leo Classen’s wartime account in Humanitas and to Agnes Krup for her German translation help.

To learn more about the people and stories featured in our episodes, please visit makinggayhistory.org, where you’ll find links to additional information and archival photos, as well as full transcripts.

This special series on the experiences of LGBTQ people during the rise of the Nazi regime, World War II, and the Holocaust is a production of Making Gay History, in partnership with the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale University.

I’m Eric Marcus. Until next time.

###