Epilogue

Plaque at the former Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria in commemoration of gay victims of the Nazi regime. Unveiled in 1984, it was the first memorial of its kind. The words “Totgeschlagen, Totgeschwiegen” mean “Beaten to Death, Silenced to Death.” Credit: Via www.gwiku18.at.

Plaque at the former Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria in commemoration of gay victims of the Nazi regime. Unveiled in 1984, it was the first memorial of its kind. The words “Totgeschlagen, Totgeschwiegen” mean “Beaten to Death, Silenced to Death.” Credit: Via www.gwiku18.at.Episode Notes

In this final episode, we reflect on why there are so few testimonies from LGBTQ people who survived the Nazi era and on the responsibility we have to honor the testimonies we do have in the face of the unfolding dark times here at home.

Episode first published April 10, 2025.

———

Audio Sources and Excerpted Writings

- Audio of the 1990 interview with Josef Kohout used by permission of QWIEN, the Center for Queer History in Vienna.

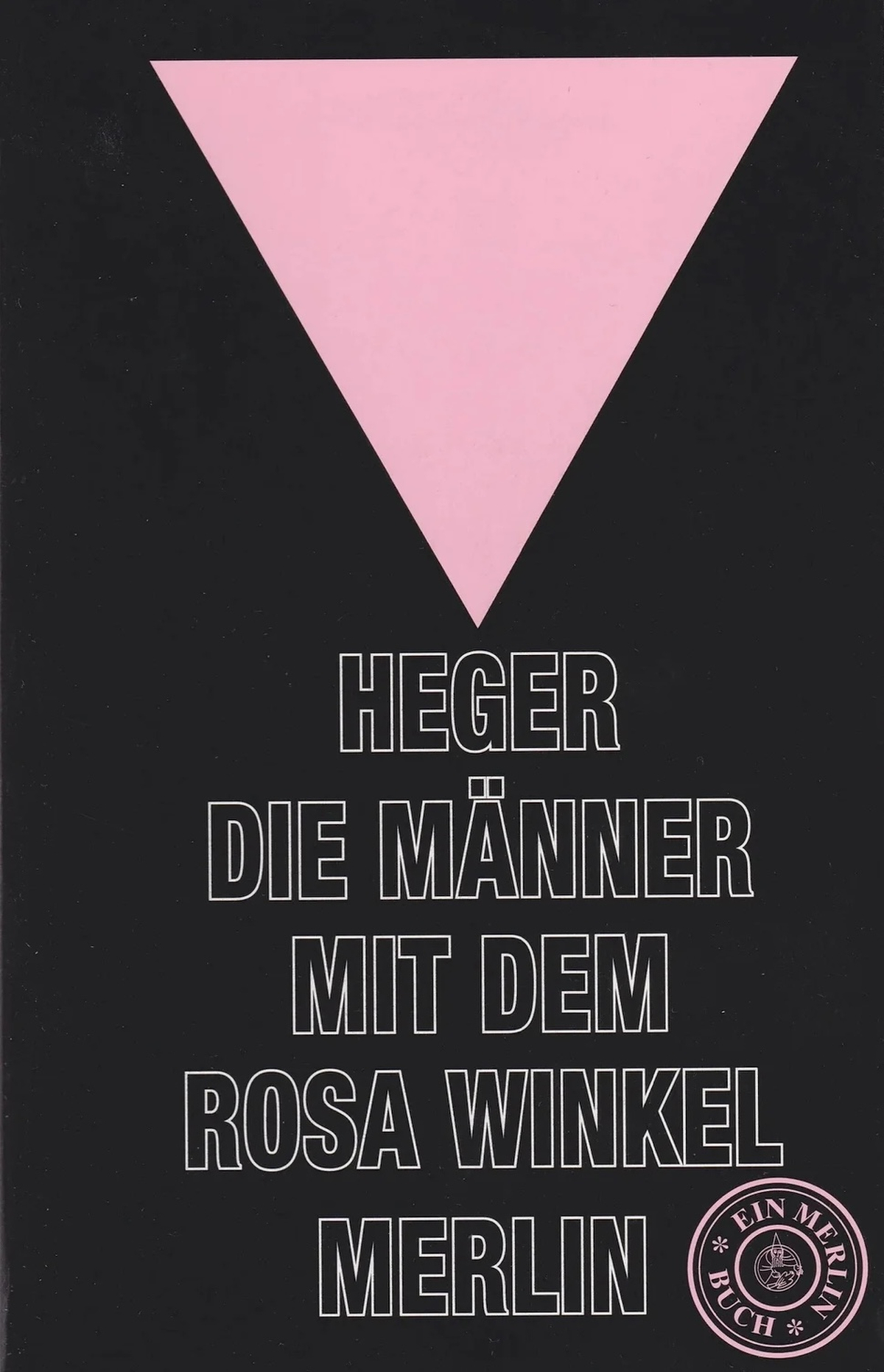

- The Josef Kohout book excerpt is from Heinz Heger’s The Men with the Pink Triangle, Haymarket Books, Chicago, 2023. Used by permission of the publisher. Original German edition Die Männer mit dem rosa Winkel © 1972/2014 MERLIN VERLAG Andreas Meyer Verlags GmbH. & Co. KG, Gifkendorf, Germany. English translation by David Fernbach © 2004 MERLIN VERLAG Andreas Meyer Verlags GmbH. & Co. KG, Gifkendorf, Germany.

- Audio of Dr. Walter Reich and Rabbi Sharon Kleinbaum from the October 10, 1996, ceremony courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C.

- RG-50.030.0841, oral history interview with Gary H. Philipp, courtesy of the Jeff and Toby Herr Oral History Archive, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C. For more information about the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, go here.

———

Resources

For general background information about events, people, places, and more related to the Nazi regime, WWII, and the Holocaust, consult the online Holocaust Encyclopedia of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM).

- Pink Triangle Legacies: Coming Out in the Shadow of the Holocaust by W. Jake Newsome offers an in-depth overview of the Nazi persecution of LGBTQ people as well as the postwar struggle to have them recognized, compensated, and commemorated as victims of the Nazi regime (Cornell University Press, 2022). For an analysis of the different ways in which gay communities in Europe and the U.S. grappled with this history, see Erik N. Jensen’s article “The Pink Triangle and Political Consciousness: Gays, Lesbians, and the Memory of Nazi Persecution” (Journal of the History of Sexuality, Vol. 11, No. 1, Jan. 2002).

- Read about Josef Kohout’s time in Sachensenhausen and Flossenbürg in the seminal 1972 book The Men with the Pink Triangle (Haymarket Books, 2023). It was published under the name Heinz Heger—a pseudonym for Hans Neumann, an acquaintance of Kohout’s. Read a biographical overview of Kohout’s life on this webpage of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM). The USHMM houses Kohout’s wartime papers and the pink triangle badge he was forced to wear, which is part of the museum’s permanent collection on the Nazi persecution of LGBTQ people.

- For background on the 1996 USHMM ceremony featured in the episode, read this article (Jewish News of Northern California, April 26, 1996).

- Learn more about Rabbi Sharon Kleinbaum in this Beit Simchat Torah profile. To listen to an extended cut of Eric Marcus’s conversation with Rabbi Kleinbaum, go here.

- Read about Joan Nestle’s life and work in this 2020 interview on the “Last Bohemians” blog; learn more about the Lesbian Herstory Archives, which she co-founded in 1974, here.

- Gary Philipp’s entire interview with Ina Navazelskis can be viewed on the USHMM website. Listen to Eric Marcus discuss the interview with Navazelskis here.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: The world’s first memorial to gay victims of the Nazi regime was unveiled in 1984 at the former Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria. It’s a 47 by 27 inch pink granite plaque in the shape of an inverted triangle mounted on a brick wall at the southwestern edge of what remains of the camp’s detention area.

On it are the words “Totgeschlagen, Totgeschwiegen.”

“Beaten to Death, Silenced to Death.”

———

I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History: The Nazi Era.

Telling the story of the experiences of LGBTQ people during the rise of the Nazi regime, World War II, and the Holocaust means contending with scarcity. This is history gleaned from archival traces, coded language, and first-person accounts that number in the low dozens.

In this final episode, we’ll touch on some of the reasons for that scarcity. And we’ll reflect on how critical it is to remember the LGBTQ people who survived the Nazi era and warned of its horrors. Because while the Nazi persecution of LGBTQ people was unprecedented in its scale and brutality, the devaluing of queer lives and the repression of our stories didn’t begin or end with the Nazi era. In this politically charged time, that’s all too apparent. And we ignore this history and its echoes at our peril.

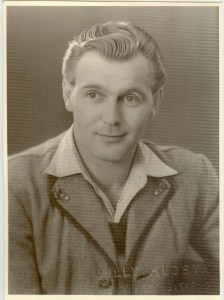

Josef Kohout was a hair stylist and post office worker from Vienna. We featured him briefly early in this series. When he was 24, he gave his boyfriend a photo for Christmas with a message of love written on the back. It fell into the hands of the Nazis.

———

Josef Kohout VO: In February 1939, on Friday the 13th, at 1300 hours, the Gestapo knocked on my door. My mother had just woken from a nap and said, “What is it?” I said, “I have to give information to the police.” But I had a bad feeling somehow and looked out of the window—I lived on a square, and the man who’d come to the door had positioned himself opposite and was watching the house. And from then on, I didn’t come home again until 1945.

———

EM Narration: Kohout spent five and a half years in Nazi concentration camps. It wasn’t until nearly three decades after the war that his story came to light when the landmark book The Men with the Pink Triangle was published. Written by an acquaintance of Kohout’s under the pen name Heinz Heger, it was the first widely available account to expose what gay men had to endure under the Nazis. The Men with the Pink Triangle is one of just a handful of first-person accounts by gay survivors of the Nazi era ever to be published.

There’s a good reason why testimonies from gay men persecuted by the Nazis came so late and why there are so few. After the war, homosexuals remained criminals under the law. Some found themselves liberated from the concentration camps only to be sent to prison to serve the remainder of their sentences.

Anti-gay laws of course weren’t uncommon at the time, but their harshness and enforcement varied. After East and West Germany were established in 1949, East Germany soon reverted back to the less draconian pre-Nazi era version of Par. 175. But in West Germany, the Nazi version remained in full force until it was amended in 1969. Until then, the police used surveillance, entrapment, and forced confessions to arrest more than 100,000 men. Nearly 60,000 were convicted. That was almost the same number of men arrested and convicted as during the Nazi era.

It’s no wonder then that homosexuals who fell victim to the Nazis wouldn’t publicly share their stories. The continued persecution meant living in fear and silence. Few gay men managed to get their Nazi era criminal convictions expunged. That also meant no economic restitution. That was the case in Austria, too, as Josef Kohout recounted in The Men With the Pink Triangle.

———

JK VO: My request for compensation for the years of concentration camp was rejected by our democratic authorities, for as a pink-triangled prisoner, a homosexual, I had been condemned for a criminal offense, even if I’d not harmed anyone. No restitution is granted to “criminal” concentration camp victims.

———

EM Narration: The process of decriminalizing homosexuality was slow. In Austria, it took until 1971. In Germany it wasn’t until 1994, after the reunification of the country, that Par. 175 was repealed altogether.

Meanwhile, efforts to get persecuted gay men recognized, compensated, and commemorated as victims of the Nazi regime often required years of lobbying. Opposition and bureaucratic foot-dragging were the norm. For other queer people who weren’t subject to systematic persecution by the Nazis, but suffered nonetheless, the path to recognition, justice, and dignity has been infinitely harder.

In the words of Pierre Seel, the Frenchman whose testimony we shared earlier in this series, “Liberation was only for others.”

The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., first opened its doors in 1993. Almost half a century after World War II, it made history as the first museum or memorial in the United States to address the fate of homosexual victims of the Nazi regime.

———

Walter Reich: The dark part of recent history to which this museum is devoted is tragic in itself. It would be more tragic still if we learned nothing from it. That’s why we built this museum, and that’s why we have devoted an exhibit in it to the terrible experience of homosexuals under the Nazis.

———

That was Dr. Walter Reich, the museum’s then director, speaking at a 1996 event to celebrate a successful campaign by the gay and lesbian community to fund more research into the Nazi persecution of LGBTQ people.

The ceremony was introduced by Sharon Kleinbaum, who was then the senior rabbi of Congregation Beit Simchat Torah in New York City, the world’s largest LGBTQ synagogue.

———

Sharon Kleinbaum: Tonight, we light this candle as a reminder that we gather here at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum to honor lesbians and gay men who were caught in a terrifying time known as the Holocaust. Our ceremony this evening is both a memorial and a celebration. It is a memorial to all those both named and nameless who were imprisoned, tortured, and who died at the hands of Nazi perpetrators during World War II…

———

EM Narration: Rabbi Kleinbaum was part of a planning committee that helped shape the museum’s permanent exhibition on the Nazi persecution of gay men and lesbians—a job that gave her an inside view of the difficulties and sensitivities involved in representing and commemorating this part of World War II history.

I spoke to her recently about some of the reasons why this history remained hidden for so long and why LGBTQ victims of the Nazi regime had to fight so hard for recognition.

———

SK: I think there was a lot of fear on the part of the Jewish community that there were attempts to dilute the Jewish, uh, experience of the Holocaust. And, um, gays and lesbians were not marked for genocide. Genocide was targeted at only two peoples in Europe and viciously successful in, for those both European populations of the Roma people and the Jewish people, and the other targets of Nazi hate and their murderous death machines were not to achieve genocide in the same way. And that’s fair to acknowledge. And then we can acknowledge those others who were targets.

And I think there was so much pain in the Jewish community and so much anxiety about antisemitism. The truth is, Jews did not acknowledge the Holocaust publicly until the publication, really, of The Diary of Anne Frank in the fifties. There were no public Jewish memorial services about the Holocaust here in the United States.

There was tremendous anxiety in the Jewish community about calling attention to it. And let’s not forget that during World War II, there was tremendous anxiety because the right wing here in America would say over and over again, “We’re not gonna die out to save the Jews, we don’t think we should fight this war for the Jews.”

And it might have been the early sixties that there was a public Holocaust memorial here in the United States. And it wasn’t until the late sixties into the seventies that there was anything that came close to Holocaust studies in any university or academic environment.

Um, so I think there was just so much anxiety, um, that I’m sympathetic to and compassionate about.

EM: And there’s also the, the issue of survivors themselves not wanting to talk.

SK: Oh. Then there’s that piece of it. Absolutely.

EM: And even non-gay survivors. I grew up in a neighborhood of survivors and refugees in Queens. No one spoke of their experiences. It really took the, the, the grandchildren of survivors to draw people out.

SK: Absolutely correct. Right. So we’re talking about very complicated layers.

EM: Yeah. So no one was gonna talk about homosexuals, not then.

SK: No. Absolutely not.

EM: Um, it really took the movement, our movement, to make it okay to be gay. You couldn’t memorialize the homosexuals, the LGBTQ people caught up in that era until it was possible to speak about them.

———

EM Narration: But even as a new LGBTQ rights movement emerged in the 1960s and gained traction in the decades after, there were good reasons for queer survivors of the Nazi era to stay silent. There was still the stigma and shame of being members of a despised minority, the risk of alienating family and community, and of facing discrimination and harassment.

It makes our responsibility to really listen to the few testimonies we have all the more essential—which is something that was very much on my mind when I spoke to Rabbi Kleinbaum just a week after the 2024 presidential election delivered a victory to those who are hostile to our communities and are determined to roll back our hard-won rights.

———

SK: We can’t control them. We can’t. But we can control the way we see ourselves and how we live our lives, and I really believe the strongest response to hate is to be more of who we are and to express it more deeply and to learn more about who we are and who those who have come before us are.

History is told through regular people, and that kind of history is us and learning about those people help us see ourselves in history, and also understand we are the ones who are actually making history.

———

EM Narration: We are the ones who make history. And as Rabbi Kleinbaum suggests, learning from our elders is an act of spiritual and political resistance. That’s never felt more true to me than in this moment, and it’s something we owe to ourselves and those who come after us. And we owe it to the LGBTQ elders who shared their Nazi era experiences when they had all too many reasons not to.

The two stories I’d like to close this series with are to me emblematic of what people had to overcome in order to speak out. And they’re also a testament to the kind of hope, courage, and resilience we can learn from—must learn from unless we’re willing to let history repeat itself.

Back in 1979, Joan Nestle, the co-founder of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, welcomed two women to her apartment on New York City’s Upper West Side. That’s where the archives were then housed. We asked Nestle to tell us about the encounter. At the core of the story is The Well of Loneliness, the groundbreaking 1928 lesbian novel by Radclyffe Hall. It was near closing time, but the visiting women lingered.

———

Joan Nestle: I would’ve defined them as straight women. They were, to me, they looked in their seventies, their hair was perfectly done, they didn’t dress like dykes. They looked like straight women, and often we, straight women did come, so…

But I said, “Would you like a cup of tea?” And they said yes. And they had very pronounced European accents, which I later realized were Polish accents, Polish Jewish accents. And so it was just me and them sitting around the big old work table of the archives, and night had fallen, and the friend of the woman who eventually spoke the words I’m gonna share with you said, “You know, my friend here has quite a story to tell.”

And then this woman—and I can see her in my mind’s eye, that perfectly coiffed hair, but that history-laden voice—said to me, “You know, I had a chance to read The Well of Loneliness before I was taken into the camps. And the way I survived being in that camp was, after having read that book, I wanted to live long enough to kiss a woman.”

And the silence that surrounded the darkness out of which those words came… And only those of us who have risked everything for a touch can know the truth: “I wanted to live long enough to kiss a woman.”

And she would say no more. I never knew her name. I never heard from her again, but she had waited to communicate, to keep this story going. She had waited and taken the risk to do it. It had to be a gift she gave, a nugget of her survival, and that’s what it was.

———

EM Narration: It was a nugget of hope and desire she felt compelled to share. But even in a safe space dedicated to chronicling and honoring the experiences of lesbians, she shared it cautiously and only when prompted by her friend.

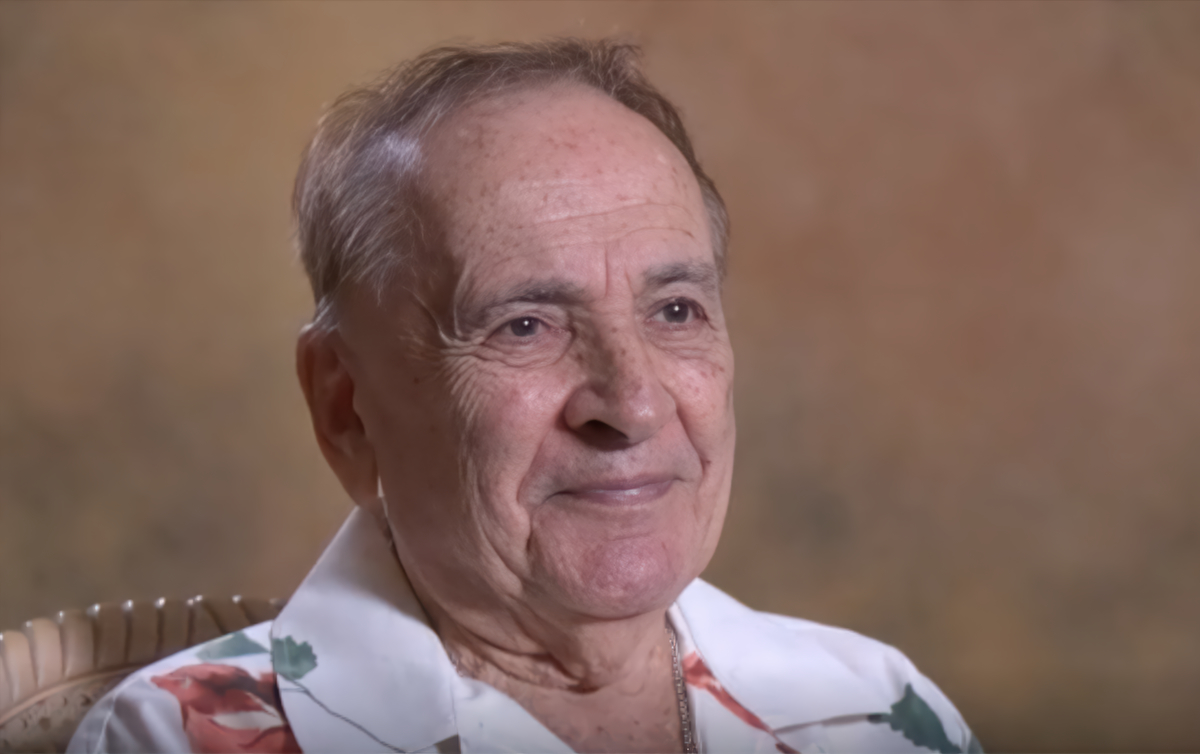

Like the Polish survivor at the Lesbian Herstory Archives, Gary Philipp needed gentle encouragement to open up. Philipp was a gay German Jew who waited seven decades to share his concentration camp experiences. At the age of 88, he recorded his testimony for the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in an interview with Ina Navazelskis.

———

Ina Navazelskis: Gary, you mentioned, uh, you mentioned some of the episodes that you went through, and, um, I want to ask you now about some much more personal things, and I, um, I apologize in advance for the prying that this involves. But I think, the reason why I am doing so is so that people in the future would have a much clearer sense of exactly what kind of danger, what kind of suffering, um, people went through when they had no power, when they were completely helpless.

So, if we could start with this incident—when you were in Sachsenhausen and someone pulled you aside, what did that entail? This man pulled you aside—he was a kapo, is that correct?

Gary Philipp: Yes.

IN: And—

GP: Well, it—when he looked at me, and I looked at him, I knew exactly—I was, my instinct told me—I knew exactly what it meant, right then and there. I knew that.

IN: And what did it mean? What did it mean?

GP: Well, it meant that he wanted to, if I like it or not, I have to sleep with him. I have to have, um—

IN: I understand.

GP: And I did this for several weeks.

IN: Was this—

GP: Several weeks, as long as I was in that camp.

IN: Was this the first time something like that…?

GP: That was the first time. Not, not before.

IN: Not before.

GP: No, not before, no.

IN: So in other words, it’s your first sexual experience.

GP: Yes.

IN: And it happens in this way.

GP: Yes. I had another, I’d—it was not a sexual experience. When we were in Ru—in Russia. We went out to, um, some, some place in the country—it was some big building, I don’t know what it was—to work some—something there. And I, I walked away a little bit from, uh, from the building. I was all by myself, standing by a tree. And out of the blue skies came a soldier, a German soldier. And he looked me deep in the eyes, and he said, um, he said to me, uh, “You want to get away from all this? You want to go with me?”

And I hesitated, of course. I said, “Yes, no, yes, no.” Maybe it’s a good thing I didn’t do that, because I probably would be—we probably both would be caught and would be shot. So that was another experience in that gay experience.

IN: Did you know you were gay at that age?

GP: I was just young.

IN: That’s what—

GP: I just didn’t, I just didn’t know. I didn’t know. I thought I’ll grow—I thought I would outgrow it, you know? I didn’t know. I didn’t know. And I, sex was not on my mind—

IN: Survival—

GP: … in all—in all these, uh, you know.

IN: I can imagine that it wouldn’t be.

GP: No, sex was not on my mind.

IN: And how, how were you able to deal with this? I mean, I, I can’t imagine what…

GP: I just, I just lived from day to day, that’s what you do. You cannot think of tomorrow, or day after tomorrow. You’re just so… I can’t believe it, to be honest with you. I think about it night and day. I can’t believe it today, that this happened, that this happened, this whole thing. That this happened to me. That I’m still here. I’m still here. Because it’s very, uh, stressful.

IN: Of course.

GP: Very stressful. I have nightmares.

IN: Still.

GP: I do, yeah. I dream a lot.

IN: And it’s about those times?

GP: Yeah, it’s always about power, and, uh, not having the power, and being, uh—can’t do what you want to do, somebody’s following you. It’s always in that direction, yes.

IN: Thank you Gary, for opening up like this. I, I apologize, and I appreciate it.

GP: Yeah, you’ve been very good.

IN: Thank you.

GP: You’ve been very good during this. It went easy, better than I thought.

IN: I’m glad.

GP: I had sleepless nights about this, I really did.

IN: I believe you, I believe you.

GP: Mm-hm, I did. I really don’t like to talk about it, and—because it’s, uh, it is terrible at night for me, the nights are terrible.

IN: I, I wish there wasn’t such a cost, and I appreciate that despite the cost, you have agreed to speak with us. It is, it is a real gift, and I thank you for it.

GP: I thank you for taking the time, and I hope it, um, I hope it never happens again like that, but—

IN: I hope so, too.

GP: It’s unbelievable, you know?

IN: Once more, thank you.

GP: I thank you for being so patient with me.

———

EM Narration: Gary Philipp’s interview brings home the extraordinary value of the testimonies we’ve shared in this series. They bring to light our hidden past and remind us of the countless unrecorded lives that were lost, destroyed, and silenced during the Nazi Era and beyond. And they carry warnings for the future that demand our vigilance. As we witness hatred, discrimination, and violence in the present and face the unfolding dark times here at home, we cannot let them go unheeded.

———

This episode was produced by Inge De Taeye, Nahanni Rous, and me, Eric Marcus. It was mixed and sound designed by Anne Pope. The voiceover of Josef Kohout was provided by John Cariani.

Our studio engineer was Elvira Gutierrez at CDM Sound Studios. Our music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Thank you to our photo editor Michael Green, our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham, and our founding production partner, Jenna Weiss-Berman.

Many thanks to QWIEN, the Center for Queer History in Vienna, for the recording of the 1990 interview with Josef Kohout and to Agnes Krup for her translation help.

Thanks also to Haymarket Books for their permission to excerpt Heinz Heger’s The Men with the Pink Triangle.

The oral history excerpt of Gary Philipp came to us courtesy of the Jeff and Toby Herr Oral History Archive at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., which also provided the audio of the ceremony held there in 1996.

Many thanks to Joan Nestle for sharing her story, and to Elizabeth Kulas, who recorded the interview.

And thank you to Rabbi Sharon Kleinbaum for sharing her insights and providing context.

To learn more about the people and stories featured in our episodes, please visit makinggayhistory.org, where you’ll find links to additional information and archival photos, as well as full transcripts.

This special series on the experiences of LGBTQ people during the rise of the Nazi regime, World War II, and the Holocaust is a production of Making Gay History, in partnership with the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale University.

It was made possible thanks to the ongoing support of the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, the Calamus Foundation, and Christopher Street Financial. Additional funding for this season was provided by Eric Lee, the Zegar Family Fund, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, the Eicholz Scott Family Trust, the Embrey Family Foundation, the Kipper Family Foundation, Esmond and Jerome Harmsworth, Andra and Irwin Press, David Quirolo, Christine and Bryan White, and the Rubin and Gloria Feldman Family Educational Institute.

We’re also grateful for the generous contributions of Ty Ashford and Nicholas Jitkoff, Mary Cadagin and Lee Wilson, Kathy Danser, Robert Dodd, Mitchell Draizin, Rick Fishell, Rick Hoffman, Michael Longacre, Robb Marchion, the Marcus Family Foundation, Eric Schuman, and Lisa Malachowsky, who made a donation in support of this series in honor of our fellow Vassar grad, the late legendary activist Urvashi Vaid.

And, finally, thank you to Bill Kux who helped underwrite this series in memory of his parents, Richard and Barbara, who gave him a foundation in kindness, respect, and social responsibility.

I’m Eric Marcus. Until next time.

###