Morris Kight

Morris Kight (right) with Harvey Milk, 1978. Credit: Courtesy of the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Morris Kight (right) with Harvey Milk, 1978. Credit: Courtesy of the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.Episode Notes

Morris Kight had a lot to say. From the moment I arrived at his front door in Los Angeles on August 1, 1989, until he closed the door behind me hours later, Morris regaled me with stories of his activist adventures and accomplishments. It wasn’t so much an interview as it was a lecture, one conducted at such high speed that it made transcribing the interview a special challenge.

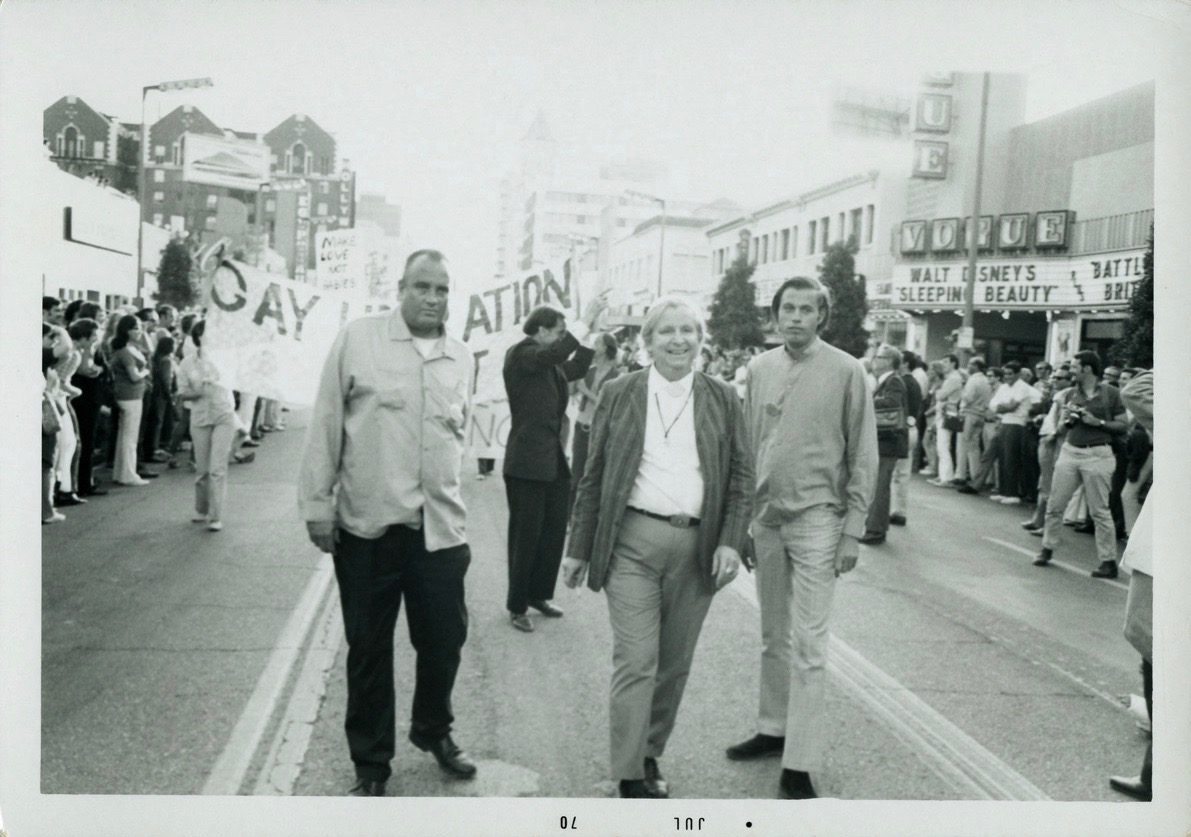

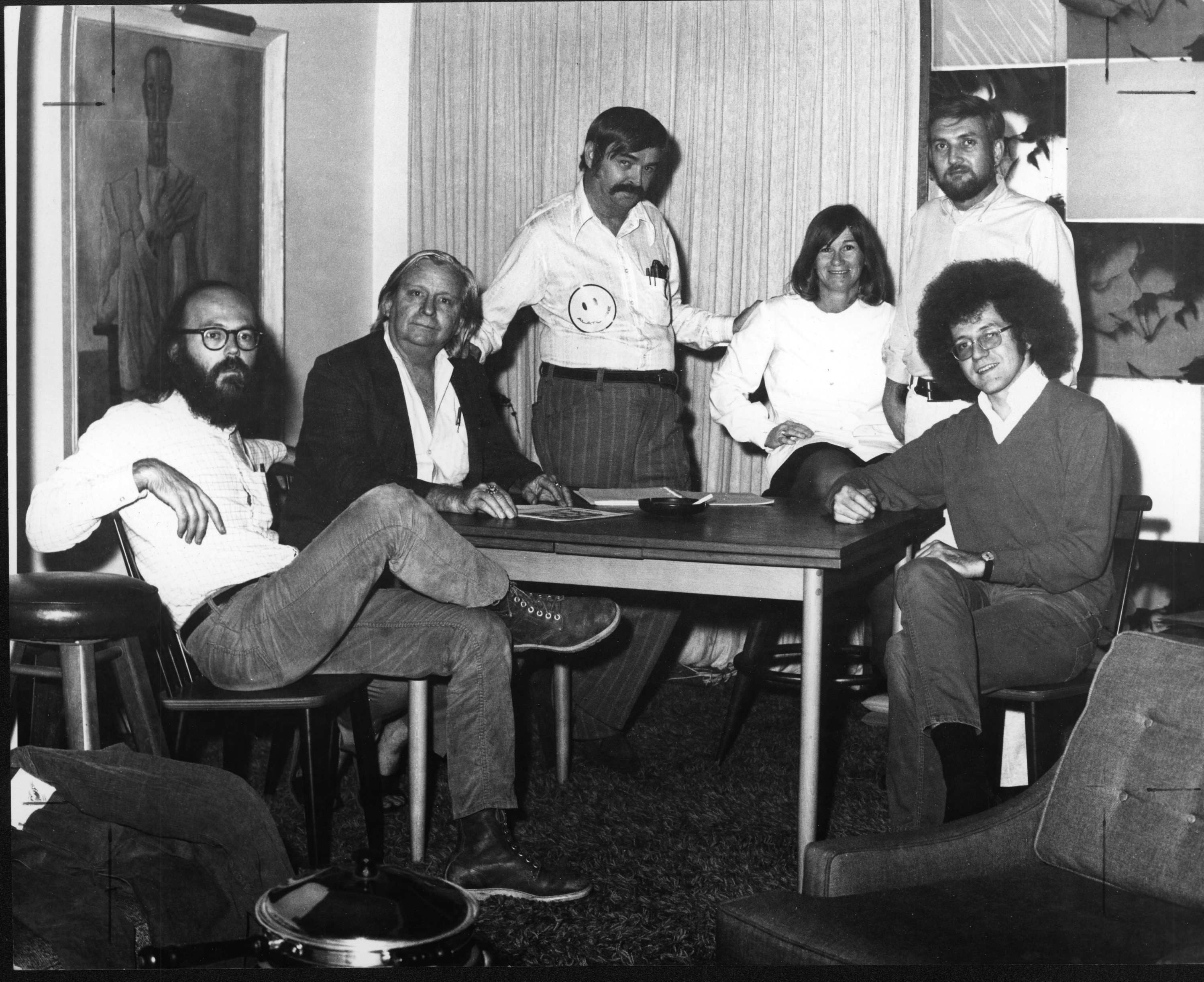

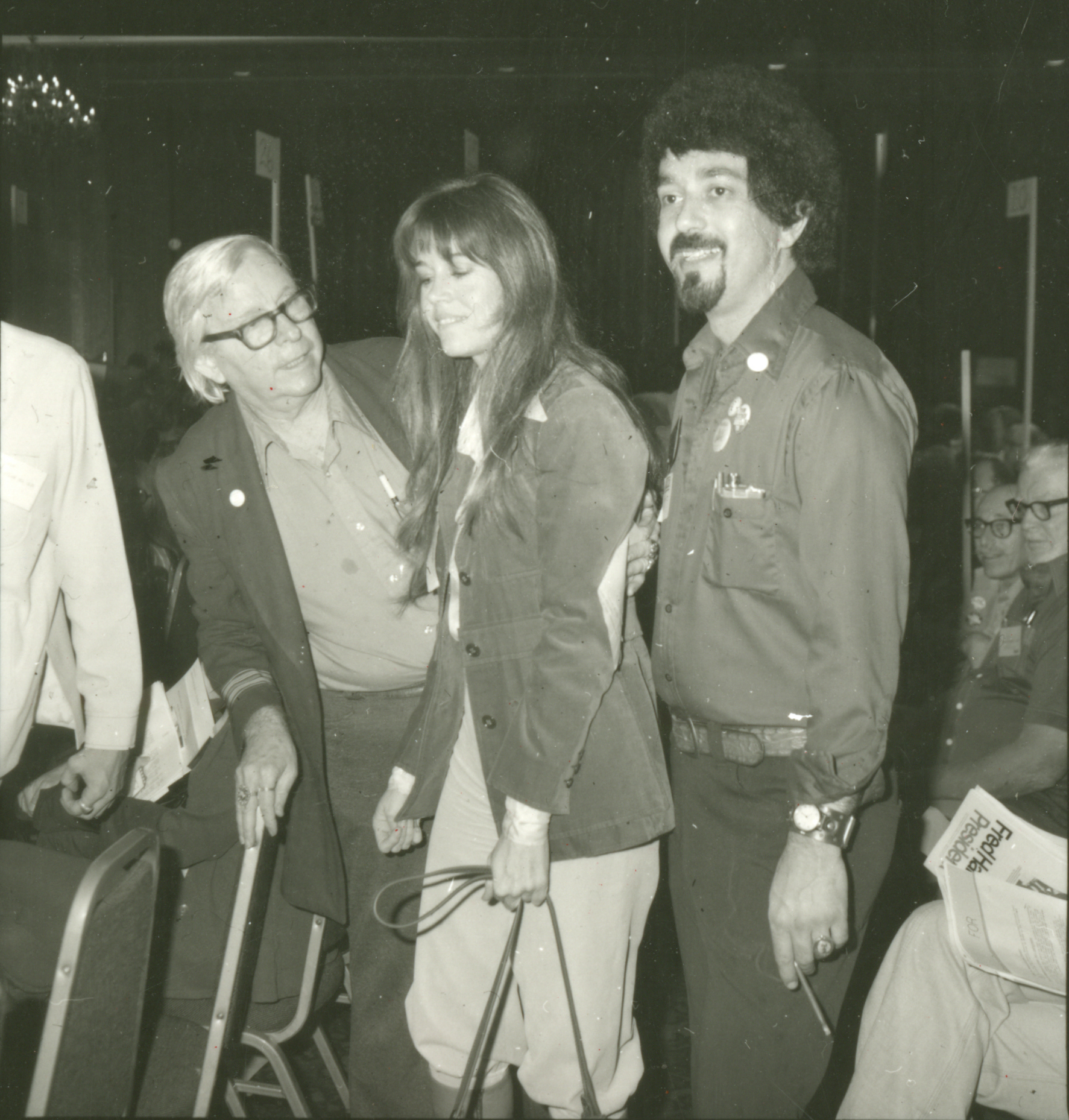

While I was tempted to dismiss a lot of what Morris said, once I looked past his hyperbole and self-aggrandizement (and fact-checked the interview), it became clear that he was indeed a major force in the fight for LGBTQ equal rights in Los Angeles—and he was literally at the front of the parade. As you’ll see from the photographs we include below, Morris was everywhere beginning in 1969 and continuing for years afterwards.

Unlike the majority of the activists from the time during which Morris made his most significant contributions, he was not young. By 1969, he was already a veteran of multiple political and social movements, including the labor movement, the fight for civil rights, and the anti-war movement. And he brought all that experience to bear on his role as an outspoken leader in the fight for LGBTQ equal rights.

To learn more about Morris, have a look at the information, links, photographs, and episode transcript that follow below.

———

For a book-length overview of Morris Kight’s life and work, check out Morris Kight: Humanist, Liberationist, Fantabulist: A Story of Gay rights and Gay Wrongs by Mary Ann Cherry. There is also a Morris Kight Facebook page.

The LGBT_History Instagram account offered a concise summary of Morris Kight’s life and contributions on November 19, 2017, what would have been Morris’ 98th birthday .

Morris Kight’s papers and photographs are housed at the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

In his Making Gay History interview, Morris talks about the horrific March 1969 beating death of Howard Effland at the hands of Los Angeles police, which galvanized local activists. You can read about the murder here and here.

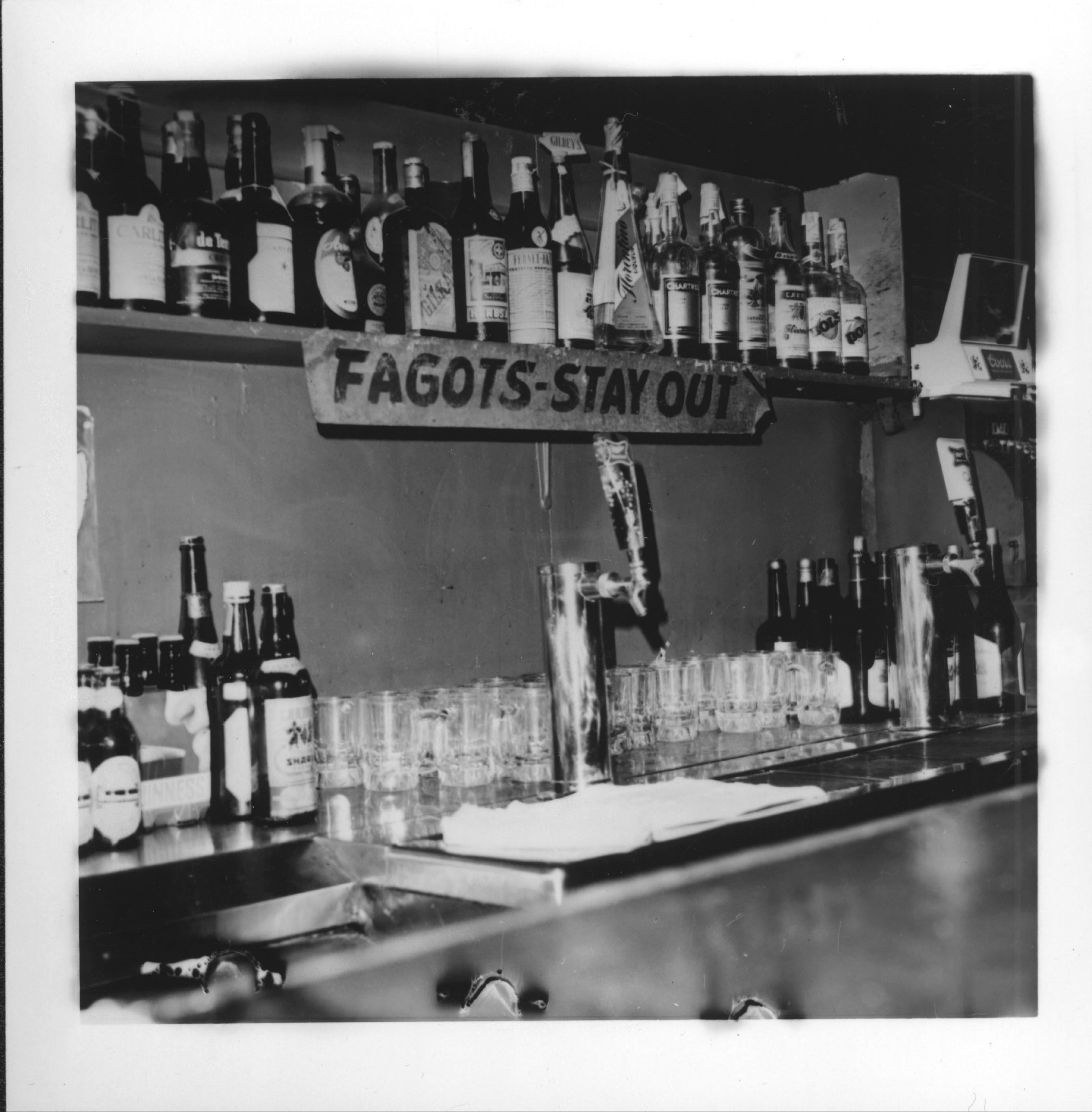

The fight over an anti-gay sign at Barney’s Beanery, a Los Angeles restaurant, was the focus of the first major protest organized by the Los Angeles Gay Liberation Front, which was cofounded by Morris Kight (and was a sister organization of New York City’s Gay Liberation Front, which was founded immediately after the Stonewall uprising in June 1969). Read about the Barney’s Beanery protest here and and counter-protest here.

Morris Kight co-founded the Los Angeles Gay and Lesbian Community Services Center in 1969. Today the Los Angeles LGBT Center is the world’s largest.

Watch Morris Kight deliver a speech at New York City’s 1973 Pride march and rally in this LoveTapesCollective video (starts around 8:20, after introduction by Vito Russo).

In 1975, Morris Kight co-founded the Stonewall Democratic Club.

Morris Kight’s house (where he lived prior to his Making Gay History interview) is listed as an historic site by the Los Angeles Conservancy.

Morris played the grumpy poet in Leather Jacket Love Story (1997), a film about a gay aspiring poet in L.A. He’s also the subject of the short film Live on Tape: The Life & Times of Morris Kight, Liberator (1999).

Morris Kight died on January 19, 2003. His obituary appeared in the Los Angeles Times.

———

Episode Transcript

I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History!

One of the things that I quickly learned when I first started researching the LGBTQ civil rights movement was that the movement was local. Every city had its own history. And every history had its own cast of characters. And some of those characters were real characters. Like Morris Kight—a high-energy, high-drama Texas native who found his way to Los Angeles in the late 1950s.

Before founding the L.A. chapter of the Gay Liberation Front in late 1969, Morris focused his passion for social justice mostly on labor organizing, civil rights, and the anti-Vietnam War movement. On the side, he informally helped LGBTQ people with referrals and resources during an era when gay people faced routine discrimination and worse.

With the founding of the Gay Liberation Front, Morris devoted all his energy to the LGBTQ civil rights movement, earning a reputation as a dogged, creative, and at times limelight-hogging crusader.

So here’s the scene. I’ve pulled up in front of 1428 North McCadden Place in Hollywood—a windowless, mustard-colored shack that from the outside looks like no one should be living in it. Two cars are parked in the packed dirt front yard. There’s a rundown apartment house next door. Loud music is blaring from an open window. I’m thinking I’ve come to the wrong place. But I knock on the door and I’m greeted by Morris. He’s a stout man of about 70. He’s dressed all in white, which matches his neatly combed hair.

The inside of the house is a surprise. Morris leads me into a light and airy double-height room that rises to the roof. There’s artwork everywhere—Morris tells me that he calls it the “McCadden Place Collection.”

Morris has clearly prepared for my visit because there’s a mountain of printed materials on the table in front of where he’s arranged two comfortable chairs. As I’m setting up my tape recorder, Morris is pulling clips and photos and flyers from the teetering pile and launches into rapid-fire tales of past battles and accomplishments. I get him to pause for a second, so I can clip a microphone to his shirt. I press record just as Morris points to a sign hanging on the wall of his living room that has a story all its own.

———

Morris: …and then the “Faggots, Stay Out” sign, from Barney’s Beanery, retrieved there in January 1970, by me. It’s an artifact. It’s like—it’s like a piece of the True Cross to Catholics, or a bit of the Ark of the Covenant to Jews, uh, I mean, it’s a shrine! People weep when they see it. They burst into tears!

Eric: Why don’t we stop here a second and, and talk about what this is?

Morris: Yes.

Eric: Um…

Morris: Under pretty much national policy and law, before liberation, in any jurisdiction of the country that I ever heard of, if a number of well-known, or known, or identified, or seemingly-identified homosexuals came to a place of public accommodations, it could be closed up.

The California Alcohol and Beverage Control Board and the sheriff department of the county of Los Angeles, West Hollywood jurisdiction, went to Barney Anthony, a bonhomie, uh, stunning host, he knew all how to make people feel good, and so on. And West Hollywood was a low-rent district at the edge of showbiz, and traffic was easy from there into wherever, and so it attracted artists, writers, creative types, and a good many homosexual men and some lesbian women.

Eric: And this…

Morris: …and a great many of us went to Barney’s Beanery. So the ABC and the West Hollywood sheriff station came to see Barney Anthony, owner of the place, saying, “Barn, your joint’s picking up a name, and a reputation of fag bar, if you don’t get rid of them, we’re gonna close you down.” So he whipped out a pencil and crudely made a sign: “Fagots” (F-A-G-O-T-S) “Stay Out.” Fagots—that’s an OK spelling of the word, by the way. Two g’s or one g are, are permissible. And there it stood, all those years, as just a terrible insult.

Eric: When did this sign first go up?

Morris: The late ’50s is this person’s belief, however that should have a question mark behind it. There’s some belief it was much earlier than that. In any case it became very infamous. Um…

Eric: But you still went. Or no?

Morris; Oh, no, I would never think of going there.

When I founded the Gay Liberation Front in Los Angeles, being a longtime community organizer, I know that people have to have a measurable, chewable, doable, dramatic issue as a first order of business. It can’t be ephemeral, it can’t be, uh, victory in the future, it has to be right now. At the founding meeting I suggested that we tool up to go to Barney’s Beanery.

And then in January of 1970, we were at Barney’s Beanery for three weeks of picketing, boycotting, uh, change-in, sit-in, and cash-in.

Eric: What—you have to explain to me what those things are.

Morris: Uh, boycott is where you urge people not to trade there. We would intervene customers on the sidewalk saying, “This place is offensive to homosexuals because of the sign inside. We urge you not to trade there.” And they’d go away!

Eric: Were there, were there dozens of protesters? Hundreds of protesters?

Morris: Oh yes, a lot. Yes. I would think 150, uh, separate persons demonstrated over a period of time.

Morris: Change-in. You’d go to the cash register and say, “Could you break this bill for me? Oh, no, I, maybe I shouldn’t break the twenty. Maybe just a ten. No, no, just let me have it all back, I’ve changed my mind.” Um, a shop-in, you say, “You have a lot of different brands of beer. You have Carlings? Mmmm, Carslberg, you have that? Uh, Coors, oh I couldn’t drink Coors. Uh, Hamms, you have that?” And so on. And you bug ‘em.

And, and a shop-in, you order things, terribly inexpensive, and you sit with a cup of coffee until it turns to ice, occupying a table and when they ask you to leave, you say, “Well, there’s no rule around here! There’s no rule about when I have to leave. I’m enjoying myself.”

Eric: So the purpose was to…

Morris: …get them to, one was remove the sign, and to promise never to discriminate against homosexuals in service or employment ever. And they ultimately agreed to all that.

Eric: And they gave you the sign.

Morris: Yes. And there it hangs.

Eric: To someone—I’m, I’m 30. Uh . . .

Morris: I know. I know. Isn’t it emotional?

Eric: To someone like me that seems remarkable that that ever would have hung in a public place.

Morris: Well, you see, we were defenseless. Until 1969, we had no defenses of any kind. There was no one to defend us, there was no one to advocate for us. There was no movement. There was nothing. No thing. Nothing.

Uh, uh, the last Sunday in uh, in, uh, in June of 19, uh, 68, the police came into the Dover Hotel, which was on South Main Street, which was, uh, the earliest gay ghetto in Los Angeles. It was downtown. The Dover Hotel, uh, was a, uh, five-story, uh, hotel in the neighborhood that became a very gay place.

And, uh, and so Howard Efflund checked in there on the last Sunday in June of 1968. And lay in his room, nude, uh, and, uh, five police officers came in, handcuffed him, and dragged him out of his bed, uh… They, uh, kept beating him with billy clubs, they dragged him down five flights of metal fire escape stairs, with his head hitting the steps, and by the time they got to the police car, his powerful heart gave out, and he died in the police car. And, uh, so they murdered Howard Efflund.

Eric: For what reason?

Morris: Macho, machismo, heterosexual imperative.

Eric: Was he known to them as somebody significant? He was just another…

Morris: No! No! Absolutely not. Just a, just a gay, just a man. And, uh, our community made uh, quite a to-do about it. We demanded a coroner’s inquest, and a number of us appeared at the inquest, and, uh, and we held a, a memorial for him.

Uh, in some haste, let me mention other sources of oppression. Education—universities, high schools, textbooks, uh, taught that our love was abnormal, deviant, variant,.

Eric: Why didn’t you believe it?

Morris: Uh…

Eric: Or did you believe it?

Morris: No, I certainly never did. Never ever have I, never have I accepted the notion of my alleged inferiority. Never have I.

Eric: Not for a second?

Morris: Never for a moment in my lifetime. I, uh, I give a lot of thought to who I am and what I am about. I was born, uh, with, uh, more spirit than a number of my neighbors, and, uh, I was born gay, except that’s not the word to describe whatever it was that we were in 1919, 1929, uh, 1939, whatever we was, that’s what I was. And that made me, uh, an outlander. And, uh, rather than to internalize that, uh, I chose to externalize it, in measured stages. And when I would gain a little bit, then I would see if that would work, and I’d gain a little more.

Eric: Let’s see where we’re going to go from here.

Morris: We were still talking about symbols of oppression.

Eric: Yes.

Morris: The police, education, the state, other than the police. The church was vicious. Was, and, unfortunately, is, vicious in its dealings with us. Leviticus, Romans, and Corinthians, three best-selling books, uh of the Bible, are etched in my brain forever. One of them calls our love an abomination, and one of them suggests we be put to death.

And then, uh, the most important oppressor that we ever had was the pseudoscience of psychiatry, psychoanalysis, largely developed between 1900 and 1910 by doctors, who sniffed, “These folk are not sinful. That’s a judgment of the church, a most imperfect and unscientific organization. They’re just sick.”

They were a monolith against us because we made good trade. We made a perfect market for them to market their pseudoscience. Uh, they would come into court and testify against us and get huge fees for that. Uh, they would, uh, appear at probate hearings and testify against us.

These monsters, uh, did lobotomies, uh, aversive conditioning, behavioral modification—They provided anectine, succinylcholine, and mind-altering drugs. And, uh, electroconvulsive shock therapy. Imagine trying to burn out of your brain your love? Good grief. This is genocide.

Eric: Let’s, uh, talk about the Gay Liberation Front. You, uh, informally, semi-formally, had been dealing with gay people, gays and lesbians, for years.

Morris: Yes, I had.

Eric: What, then, led to a formalization?

Morris: I was waiting for a sign that it was time to, to go back to lesbian and gay direct services. I was doing that all along as a part of the anti-war movement, I was serving lesbian and gay people. But I was spending a lot of time demonstrating, boycotting, and organizing, and so on. And, so I took a little ad in the Los Angeles Free Press, saying I wanted to bring together homosexual persons for an organizing meeting, and…

Eric: When was this now, this was…?

Morris: L.A. Free Press was a leftist paper in the city…

Eric: Oh, so this was in 1960—November of ’69.

Morris: That’s right, November of ’69.

Eric: This was already following June ’69…

Morris: Which had not one trace of an influence upon my work.

Eric: I have the question right here…

Morris: Not one trace of influence. I had a number of telephone calls from payphones by Christopher Park, by Sheridan Square, while the Stonewall rebellion was going on, and since I was in the midst of a whole variety of rebellions, since I was up to my neck in civil disobedience, since I was up to my neck in television and radio and newspapers, I was up to my neck in organizing…

Eric: For Vietnam.

Morris: Against the war in Vietnam, and against poverty, and against racism, and against classism, and against redlining. I was involved in super-radical activities, and so I absorbed it as just one more interesting activity, except it was us instead of them. And that was the only difference, uh, that came in my mind, I said, “Well, fine, thank you for calling, that’s very interesting, I’m happy it’s happening.” Uh, the Stonewall, uh, rebellion did not influence my founding the Gay Liberation Front of Los Angeles

Eric: So you, you put an ad in for this meeting. And what occurred at that meeting

Morris: Eighteen people attended. I remember that I felt that it was a fairly conservative crowd, from what I knew about them. Uh, but I also was impressed with the fact that speaker after speaker—“What is radical mores? What does that mean? And how do we get radical?” I mean, they were ready! Ready to mobilize, ready to move, ready to offset the years of ignorance that they had to suffer.

Eric: So did you have a—an office here where people could call?

Morris: No! We did it, we did it from my home over at 1822 West Fourth Street.

Eric: So you had one phone, and people called up on that phone all day long?

Morris: 48, 484-1094. After all these years, I remember the number. It was the busiest phone you ever heard in your life. And I was eternally attracting new volunteers to staff the phone, and train them how to do that. Every call is priceless, every call is important. Have a routine that may be treated as if it’s the most urgent call you’ve ever had in your life.

The person is calling to ask you when our meeting is. They don’t want to know when our meeting is at all. They want to know, how do they get gay? How do they get out of a bad arrest, how do they get out of a bad marriage, how do they repossess their children, how do they repossess their property, how do they recover their dignity. They want to know ever so much more, so hold them on the phone until you really know that they’re going to attend a meeting and start relating to us.

By, uh, February, there were 150 people attending meetings, and by April there were 250 attending meetings. And they were held every Sunday.

Eric: What, what was it that drew people there? What were you doing that interested people?

Morris: Excitement! Action! Liberty! Liberation! Sell them on the idea of liberation. Convince them that it was the most important thing in their world, and that they can achieve that, that only they stand between themselves and total freedom.

Eric: Why was that so important? Why was liberation so important?

Martin: Well, we had to do something about the thousands of years of conditioning that had gone on to, uh, to cause us to hide out, or to believe in our alleged inferiority. Millions of gay people really did feel of themselves as inferior.

And that’s wrong, because we’re—deserve the very best. And something had to be done about that. And, uh, nobody else was going to do that for us. Nobody, at all. Only a handful of people [sneezes] from out of the radical movements that I was associated with, only a handful of people had shown a trace of charity toward homosexuality. Only a handful.

Eric: So…

Morris: Had everything in the world on their agenda, but not us.

Eric: And so you had, it was either you and the rest of the gay people here were going to do it, or no one was going to do it for you.

Morris: That’s precisely right.

———

Morris Kight spoke with such passion and conviction that it was hard to challenge him when he said things that I knew strayed from the facts. But Morris, like most of us, remembered history the way he wanted his history remembered. And that history did not include any acknowledgement of the important contributions of pre-Morris gay rights activists in Los Angeles—like the founders of the Mattachine Society. And for the record, the horrific beating death of Howard Efland took place on March 9, 1969, not the last Sunday in June 1968.

The Los Angeles chapter of the Gay Liberation Front that Morris co-founded was short-lived, but that wasn’t the end of Morris’ activism. He went on to co-found the Christopher Street West gay pride parade, the Los Angeles LGBT Center, the Stonewall Democratic Club, among other organizations. In 1998, in recognition of Morris’ many contributions to the LGBTQ civil rights movement, the West Hollywood City Council presented him with a lifetime achievement award.

Morris Kight died on January 19, 2003. He was 83 years old. He was survived by Roy Zucheran, his life partner of 25 years. He also had two daughters from a five-year marriage in the 1950s.

In the past we’ve shared messages from young listeners who are finding our history through this podcast. This note from an older listener really touched me.

Bryan DeLeo from Washington, D.C., writes: I grew up (unhappy, isolated) in the 1950s, unable to imagine acceptance during our lifetimes. Nowadays I’m regular, married, no longer an unhappy kid. Thank you again, for all the work you have done on behalf of lesbian and gay Americans.

We love hearing from you. You can send an email or a voice memo to hello@makinggayhistory.com.

Making Gay History is a team effort. Thank you to Sara Burningham, our executive producer who makes each episode sing. And thank you to audio engineer, Anne Pope, who makes certain that the episodes sing on key. We had expert production assistance from Josh Gwynn. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Thank you, also, to social media strategist Will Coley, our webmaster, Jonathan Dozier-Ezell, and researchers, Bronwen Pardes and Zachary Seltzer. Thank you to photo editor, Michael Green, whose work you can see in the episode notes at makinggayhistory.com. A very special thank you to our guardian angel Jenna Weiss-Berman.

The Making Gay History podcast is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and ONE Archives at the USC Libraries. Shortly before his death, Morris donated his entire collection—including thousands of documents and the McCadden Place Collection to the ONE Archives. You can find a link to that archive in Morris’ episode notes at makinggayhistory.com.

Season three of this podcast is made possible with funding from the Ford Foundation, which is on the front lines of social change worldwide.

And if you like what you’ve heard, please subscribe to Making Gay History wherever you get your podcasts. You can also go to makinggayhistory.com.

So long! Until next time!

###