Meg Christian

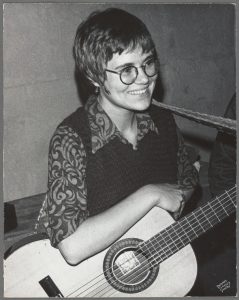

Meg Christian, 1981. Credit: Photo by Irene Young.

Meg Christian, 1981. Credit: Photo by Irene Young.Episode Notes

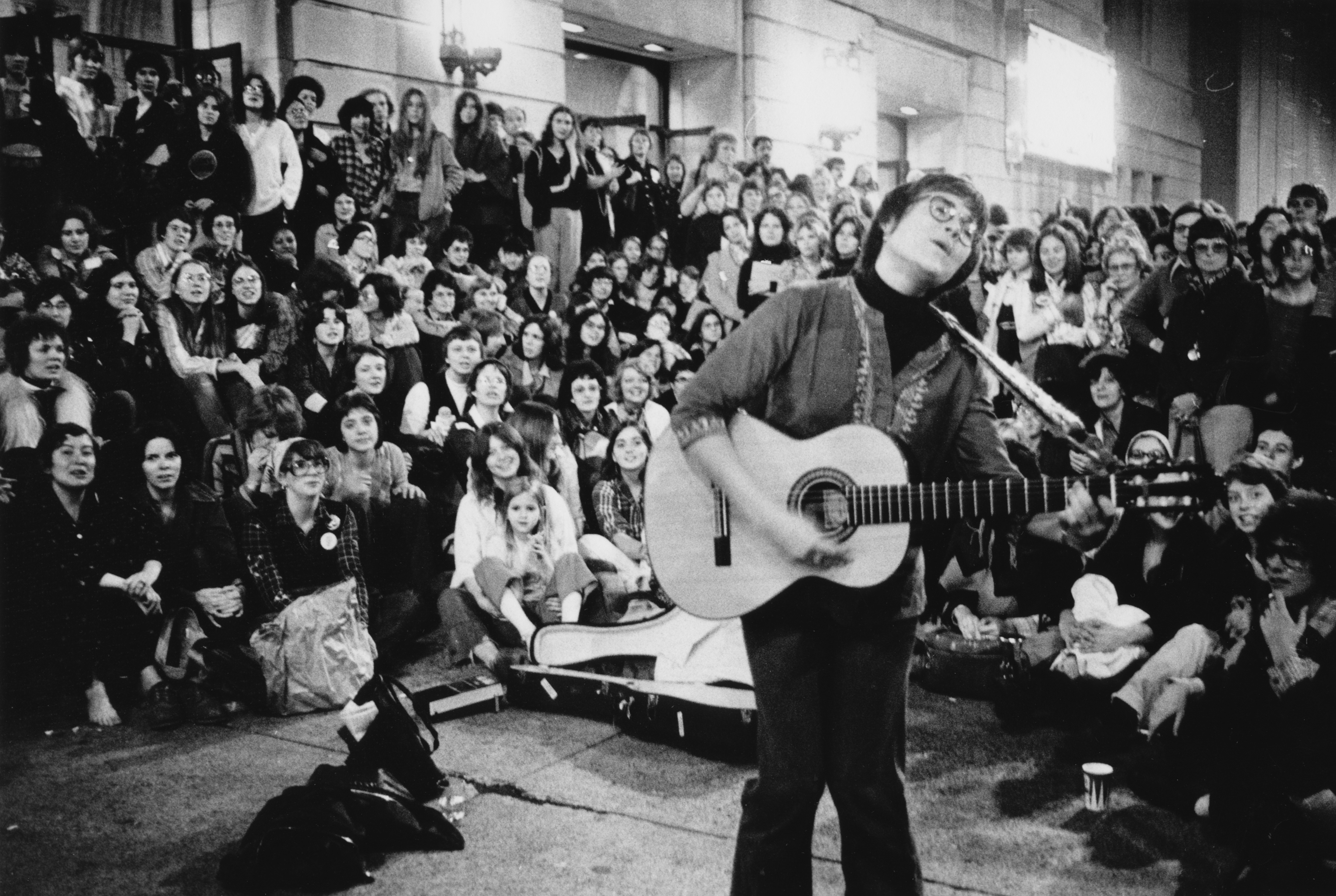

Olivia Records cofounder Meg Christian helped ignite the women’s music movement of the 1970s with lesbian classics like “Ode to a Gym Teacher.” Meet Meg, in song and conversation, in our final episode drawn from the Studs Terkel Radio Archive.

Episode first published January 7, 2021.

———

Meg Christian was a central figure in the lesbian feminist movement of the 1970s. Find out more about the celebrated singer-songwriter and activist in this short biography and this 1978 artist profile. Explore her music through this fan channel.

For a deeper dive into Christian’s work, head to Queer Music Heritage, where you can find a wide-ranging collection of articles as well as Christian’s discography and album covers. While you’re there, listen to JD Doyle’s tribute episode to Christian (or read the transcript here).

Before Christian became a “founding mother of women’s music,” she started out as a performer of other artists’ songs; read about the early days of her music career in this Off Our Backs interview.

In 1973 Christian joined with other musicians and former members of the lesbian collective the Furies (check out their publication here) to found the independent record label Olivia Records. Learn more about Olivia Records here and in this company timeline. And read this 1979 interview with Christian and Olivia cofounder Ginny Berson, as well as this 2020 interview with Olivia artist and producer Linda Tillery.

Olivia Records released over 60 singles and LPs; listen to some of the label’s most influential songs in this New York Times compilation. The label’s first release was a fundraiser single that featured a song by Christian and one by Cris Williamson. Christian and Williamson sang together many times over the years, including at a 10th anniversary concert for Olivia Records at Carnegie Hall; you’ll find samples here.

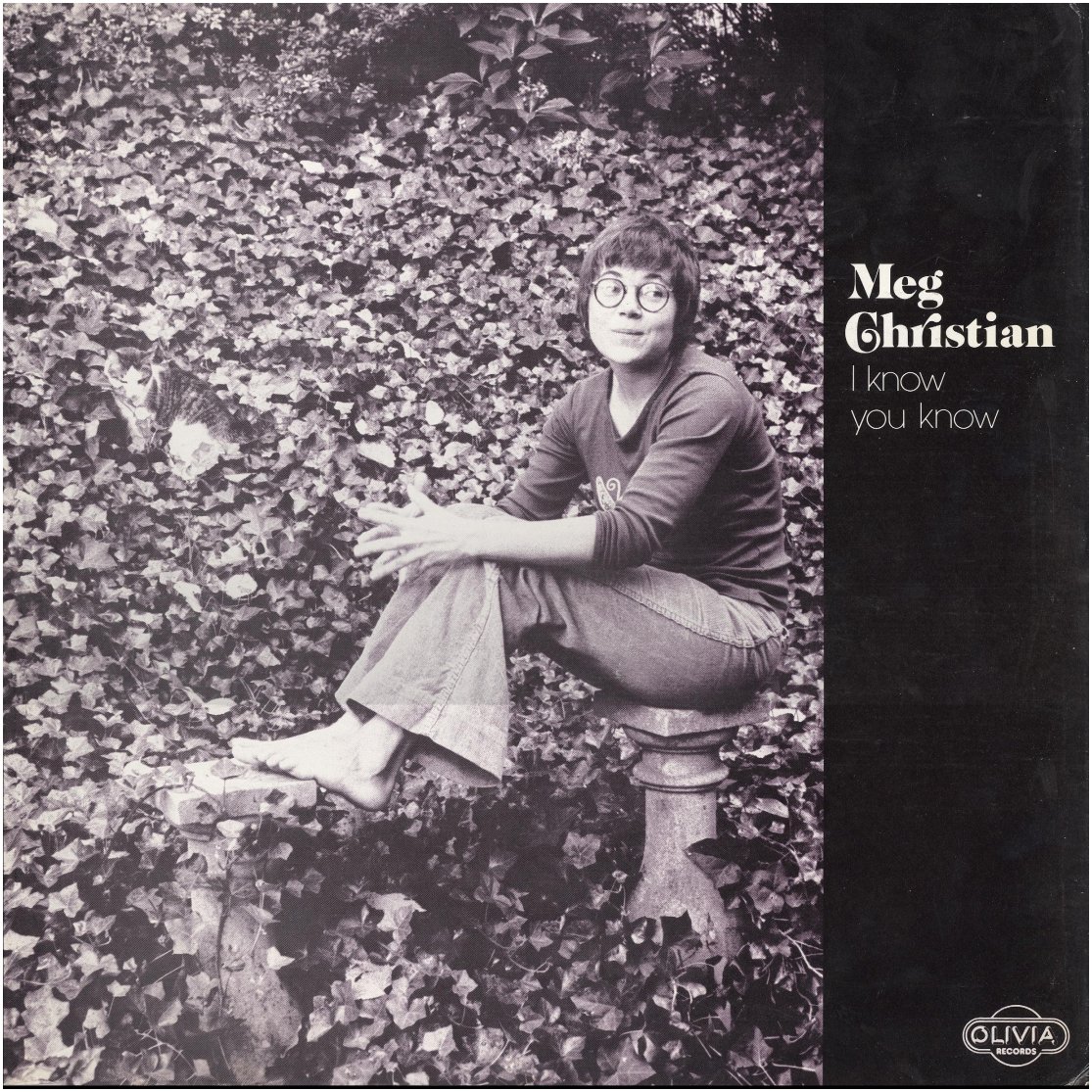

Olivia’s first LP release was Christian’s 1974 album I Know You Know (which included “Ode to a Gym Teacher”). Her second album, Face the Music, followed in 1977; it featured 35 women musicians and included Christian’s cover of Sue Fink’s “Leaping Lesbians.” In 1981, she released Turning It Over (which included “Southern Home”).

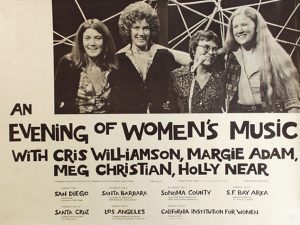

For more on the women’s music movement, watch the documentary Radical Harmonies and listen to this panel discussion featuring Christian and Holly Near.

In the fall of 1977, Christian confronted her dependence on alcohol with the help of the Alcoholism Center for Women (ACW) in Los Angeles. She often shared her story of recovery; hear her in this panel discussion on lesbians and alcoholism from the radio show Lesbe Friends (at 22:40, she sings a song she wrote for the ACW; lyrics here).

Christian often lent her support to political causes (listen to an example here). In response to Anita Bryant’s “Save Our Children” campaign, Olivia Records released Lesbian Concentrate: A Lesbianthology of Songs and Poems; explore it here. Christian sang at the 1979 March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. Hear her discuss 12 years of lesbian activism alongside Barbara Cameron, Ginny Berson, and Pat Parker.

In 1984, Christian left the music scene. She joined an ashram in upstate New York and changed her first name to Shambhavi. She works at the SYDA Foundation, a nonprofit that serves to protect, preserve, and facilitate the dissemination of Siddha Yoga teachings.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus, and this is Making Gay History.

When I listen to the decades-old interviews we’ve been sharing from the Studs Terkel Radio Archive, I tend to reflect on where I was in my own life when people like Leonard Matlovich and Jill Johnston were experiencing milestones in theirs. Or lesbian folk singer Meg Christian, who we’re featuring in this final episode of our eighth season.

As you’ll hear, 1969 was a turning point for Meg. For me, that year mainly brings back memories of Mrs. Green’s fifth grade class at PS 99 in Queens, New York, but outside my prepubescent bubble, LGBTQ history was being made. 1969 was Stonewall. It was the dawning of the gay liberation phase of the movement.

And for Meg Christian, it was the year of her feminist awakening, a new consciousness that found heartfelt and witty expression in songs that came to define women’s music.

Women’s music was a movement all its own in the 1970s. It was about social change, feminist solidarity, and self-empowerment. And, more often than not, it was about lesbian love and pride. Not surprising since lesbians were the driving force behind the movement.

That’s where Meg Christian played a major role. In 1973, Meg and a collective of like-minded lesbians founded Olivia Records. It was a groundbreaking independent record company for women and by women. What the Olivia collective lacked in capital and experience, they made up for in talent and vision. Both on stage and behind the scenes, Olivia provided an antidote to the straight boys’ club of the music industry, and they put women’s music on the map.

The label’s first album was Meg’s I Know You Know, released in 1975. By the time Meg sat down with Studs Terkel in his Chicago studio, she’d just released her third album, Turning It Over. Let’s join Meg and Studs for a conversation first broadcast on September 16, 1981—and for a listen to some of Meg’s classic tunes.

———

Studs Terkel: We’re gonna make this sort of, uh, an autobiography through your songs—who is Meg Christian: a portrait. Well, let’s go back to beginnings. Who are you? Where, where, where, where it began, and where you came from.

Meg Christian: Well, I was born in Tennessee in 1946 and grew up in Virginia and North Carolina. And, uh, what else would you like to know? [Laughs.]

ST: Well, beginnings, family, …

MC: Well, my father, uh, taught in universities and colleges, taught history, and, uh, he died when I was two, and my mother, um, raised me. I was an only child, still am. And she worked as a medical record librarian in Lynchburg, Virginia, and, uh, we were, we were each other’s family for my whole growing up time. And, uh, so I spent lots of time by myself, learning to play anything with strings. Started when I was five playing the ukulele and promptly sat on it and had to buy another one, and probably hit that one over someone’s head and bought another one, and, uh, finally worked my way up to, to a guitar. It was very much self-taught. I organized folk groups during the, the ’60s in Lynchburg, and, and we learned to play the guitar while listening to people like Joan Baez and The Kingston Trio and—

ST: So this is… yeah…

MC: … Harry Belafonte was big. It was interesting because I stayed very much in my own, uh, solitary shell until I got into college. I was not involved politically, but I knew growing up as a woman that I could not, I couldn’t relate to the stereotypes, the stereotype im—social images of women that kept coming my way. Um, I knew that I was different, and I couldn’t understand why my choices were, seemed to be so limited, um, why the boys in the class looked at me funny when I asked too many questions. You know, there were all kinds of little messages that something was amiss. And it wasn’t until, actually, Eugene McCarthy ran for president that I, that I sat at a booth in front of the post office in Chapel Hill and gave out pamphlets and had no idea what I was doing. But that was the beginning.

ST: And so in music, it comes out in music, doesn’t it? And “Southern Home,” this is autobiographical, I suppose, isn’t it?

MC: Very much so. It talks about that, um, very ambivalent relationship that most Southerners feel about the South, that intense love and intense embarrassment, and, uh, uh, you know, you, you grow up to believe that the South is a special, beautiful, warm, rich cultural, social place, and at the same time, you, you are taught to believe that it’s got to be the most oppressive, uh, awful place in the world for anyone, you know, who has any different ideas about life. And you grow up feeling that you’re kind of ignorant because everyone always makes fun of Southern accents. Uh, you know, I used to listen to people on TV who had accents just like me and be embarrassed hearing them talk, you know, which is a little strange.

And so for years after I left the South, I tried to learn to talk differently and pretending like I had forgotten where I was from, and not until several years later did I meet, um, some people who, uh, were proud of their heritage and who had learned to sift through and take what was beautiful and special and hold on to that. And some were even going back to, to take what they learned to do political work in the South to help make change in the, the place of their roots.

And it moved me so deeply to hear them talk that I, it allowed me to go back and, and see it differently, and accept what was always in there, the love.

ST: So “Southern Home.”

———

I was traveling around

With some friends from the South

Who’d all moved away

Soon as we could get out

Fleeing Confederate closets of pain

Losing the accents

We’d learned to disdain

Go to hell, Southern bigots and belles

But my friends now were making

Their plans to return

With all that they’d learned

To the place they were born

And the words they were saying

Just opened the door

To a love I’d been trying

So long to ignore

A longing so deep and so strong

For my Southern home

No longer to blame

For the pain that I could have found anywhere

My Southern home

Though I may not return

I reclaim your soft beauty as my own

Southern home

Southern home

Now I live in the West

And I like it a lot

But I’m holding those old

Blue Ridge Hills in my heart

I can dream of the place that has known me the best

Embrace what I’ve loved

And turn over the rest

Oh I never will lose you again

My Southern home

No longer to blame

For the pain that I could have found anywhere

My Southern home

Though I may not return

I reclaim your soft beauty as my own

Southern home

Southern home

———

ST: So it’s funny, listening to the song “Southern Home,” talking to Meg Christian, who, originally of Lynchburg, Virginia, and then University of North Carolina, talking about wanting to forget, uh, roots. And one of the lines is, “Fleeing Confederate closets of pain.” And then what happened?

MC: Well, then I, I studied classical guitar for a while and moved to Washington, DC, and found the women’s movement, and, uh, the gay liberation movement sort of simultaneously in the fall of ’69 were starting up. And I was working in nightclubs, just singing any pretty melody that came down the pike, and I suddenly realized that, um, I could take what I was learning and translate it into, into my music and start singing songs that had true things, positive things to say about women’s lives, to give us a sense about the fullness and the complexity of our lives. Um, I realize that the, that the, the images of women in popular music were limited to say the—to be kind. Insulting, usually. Um, and I couldn’t relate to ’em, and I wanted to talk to the truth. I wanted to talk about my life to people who could understand my experiences ’cause there were a lot more of us than I used to think in my Confederate closet of pain. [Laughs.]

ST: There had to be certain people, influences in your lives, weren’t there? I mean, to make you feel freer? There was a movement, but there also had to be individuals, too, weren’t there?

MC: Well, certainly, as I was growing up, I was looking around for role models all the time, you know, for women who had chosen nontraditional jobs, for women who had chosen not to marry. Um, you know, my mother was a tremendous example to me because she, she lived, you know, as a single, independent working woman, and all the other, uh, friends that I had had two parents—you know, the, the father worked, the mother didn’t. And, um, and so there were always people around. You know, I had a, a high school teacher who was a gay man who, um, who was incredibly supportive to me, uh, at a time that I needed support, ’cause, of course, I was the only one in the world.

To me, that’s the essence of it, to be reminded that we are not alone in anything that we’re feeling. ’Cause I think that will kill us faster than anything, is the feeling that we’re alone.

ST: And now “Gym Teacher.” This has a special connotation, doesn’t it, this song?

MC: Well, this is a song off my very first album, and, uh, it’s a song about role models, about my eighth grade gym teacher who I absolutely worshiped because she was one of the first women that I’d ever seen in my life who was, uh, having a nontraditional role, you know? And, uh, she was strong, and she was beautiful, and she loved what she was doing, and I thought, oh, boy, maybe, maybe there are more choices in this world than I thought there were.

———

MC: So anyway, here’s a song about my gym teacher. It’s called “Ode to a Gym Teacher.”

[Chorus:]

She was a big tough woman, the first to come along

That showed me being female meant you still could be strong

And though graduation meant that we had to part

She’ll always be a player on the ball field of my heart

I wrote her name on my notepad

And I inked it on my dress

And I etched it on my locker

And I carved it on my desk

And I painted big red hearts with her initials on my books

And I never knew ’til later why I got those funny looks

[Chorus]

Well, in gym class while the others

Talked of boys that they loved

I’d be thinking of new aches and pains

The teacher had to rub

And while other girls went to the prom

I languished by the phone

Calling up and hanging up

If I found out she was home

[Chorus]

I sang her songs by Johnny Mathis

I gave her everything

A new chain for her whistle

And some daisies in the spring

Some suggestive poems for Christmas

By Miss Edna Millay

And a lacy lacy lacy card for Valentine’s Day

(Unsigned of course)

[Chorus]

(Here comes the moral of the song:)

So you just go to any gym class

And you’ll be sure to see

One girl who sticks to teacher

Like a leaf sticks to a tree

One girl who runs the errands

And who chases all the balls

One girl who may grow up

To be the gayest of all

[Chorus]

MC: Thank you.

———

ST: [Laughs.] “You’ll always be a ball… You’ll always be a player on the ball field of my heart.”

MC: Yeah, isn’t that tender? Yeah.

ST: Oh, it’s tender and loving, isn’t it?

What is it? Is, is there a way of describing the difference in feminist music or maybe… I don’t wanna force anything, though. Um…

MC: Well, I prefer to use the term women’s music…

ST: Women’s music.

MC: … um, because for some people, feminism has a, a—people have certain, put certain emotional connotations or tend to narrow it. When I like to think of, of… I mean, because of course my music is feminist, um, and, but essentially the way I would define it for myself is that it’s music that comes consciously out of my, um, awareness of myself as a woman in the world, what that means to me, um, the insights that I’ve had about it. And, uh, that it tries to, it tries to tell the truth. It tries to give us positive images and give us support.

I spent years of my life doing intense political work to help make change, uh, within, within the, the idea of women’s issues and women’s rights. And at the same time, I was working so hard, um, that I almost killed myself. I was, uh, drinking heavily. I was, um, not resting, and I realized at some point that I was doing what, um, what I had been saying that the world was doing to me, you know? Don’t you all bother out there, I’ll take care of it myself. And that I wanted to be around for this revolution.

And, um, so for me it starts inside myself, learning to change myself, um, to create a life in which I can function. What can I do best? What can I relate to personally? Um, and what do I have the talent to contribute to?

ST: Who, who come to your concerts?

MC: Well, um, mostly women. The, all the concerts that I’m doing on this tour are open to anyone. Um, an increasing diversity of people in the audience.

ST: You say mostly women. Young women? Have, do you have older women, too?

MC: Oh, yes, definitely. Lots of, uh, generations we have coming now, lots of young children. You know, when I think about what my life would have been growing up in Lynchburg, Virginia, if I had heard this music when I was 13 years old, I would be a different person.

ST: When were you first aware that something out there…?

MC: Well, it wasn’t when I was in Lynchburg, Virginia, I’ll tell you that. [Laughs.] Uh, I had to really wait until I was in college, you know, and that to me is the exciting thing, is that the music can travel sometimes where we as, uh, physical bodies can’t get to. And the music travels and goes, and we get letters from tiny towns where you think, where on earth could they have heard that album? And they hear and they know that they’re connected. They’re connected. And so their lives will never be the same.

ST: Is there, is, are there places where you had, where you’re considered controversial?

MC: You name it. [Laughs.] A, a women’s production group in, uh, Boston, doing a concert at Harvard got sued, um, because we wanted to have one, uh, open-to-everyone concert and one all-women’s concert. And one guy who wanted to come to the all-women’s concert and refused to believe that anything could legitimately exist without his presence, sued the production company. You know, it happens everywhere.

ST: But in smaller ho—you said you performed at Salt Lake City.

MC: That’s right, just a few days ago we were there. Or was it yesterday? [Laughs.] Anyway.

ST: What happened there?

MC: Um, it was very exciting. It’s one of the first concerts of women’s music that they had there, and, uh—

ST: This is Mormon country.

MC: Uh, you bet. [Laughs.] Um, I remember I was singing, uh, one song that I do called “Leaping Lesbians,” which is on my second album, Face the Music. It’s a very funny song about the stereotypes that many of us carry around inside of us even though we pretend to be ever so open-minded. Um, and I said at one point, “Now I want you all to sing this with me loud enough so they can hear it all the way over at the Tabernacle,” and this gasp. [Laughs.] And everyone kind of went, gulp. You know, as though, we’re not sure we wanna sing it quite that loud.

But, you know, the act of coming to that concert, uh, whether or not you’re a lesbian, whether or not you were just anyone who was open to new ideas and to some support just for the idea of being a whole woman in this world, it was a risk. It was a personal, professional risk. It was a political act to come to that concert. And so the energy and the bonding that was there was quite amazing. And there were over 300 people there.

———

[Growl]

Here come the lesbians

Here come the leaping lesbians

We’re going to please you, tease you

Hypnotize you, try to squeeze you

We’re going to get you if we can

Here come the lesbians

Don’t go and try to fight it

Run away or try to hide it

We want your loving, that’s our plan

Here come the lesbians

Ah-ah-ah

Don’t look in the closet

Ah-ah-ah

Who’s creeping down the stairs

Ah-ah-ah

Who’s slipping up behind you

Ah-ah-ah

Watch out, better beware

Icy fingers feeling, stealing

Reaching out from floor to ceiling

You can’t escape, you’re in our hands

Here come the lesbians

Inside your heart is racing

When you see our shadows chasing

Here come the lesbians

(Here come the lesbians)

Here come the lesbians

(Here come the lesbians)

The leaping lesbians

Bo-de-o bo-de-o bo-de-o bo

(Bo-de-o bo-de-o bo-de-o bo)

Ah-ah-ah

Don’t look in the closet

Ah-ah-ah

Who’s creeping down the stairs

Ah-ah-ah

Who’s slipping up behind you

Ah-ah-ah

Watch out, better beware

Icy fingers feeling, stealing

Reaching out from floor to ceiling

You can’t escape, you’re in our hands

We’ll save your children

Inside your heart is racing

When you see our shadows chasing

Here come the lesbians

(Here come the lesbians)

Here come the lesbians, oh no

(Here come the lesbians)

The leaping lesbians

MC: Thank you, chorus!

———

EM Narration: Meg Christian largely retired from the music scene in 1984. She moved to an ashram in upstate New York and adopted a new first name, Shambhavi. She’s recorded several albums of devotional songs and lullabies and works at a nonprofit that spreads the spiritual teachings of Siddha Yoga.

Olivia Records transformed itself into Olivia Travel, a company that designs vacations for lesbians and LGBTQ+ women. Since 2002 Meg has performed on several Olivia cruises, revisiting her classic hits for adoring audiences.

———

Many thanks to everyone who makes Making Gay History possible: senior producer Nahanni Rous, co-producer and deputy director Inge De Taeye, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, genealogist Michael Leclerc, and social media producers Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. Special thanks to Jenna Weiss-Berman and our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Studios, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Season eight of this podcast has been produced in association with the Studs Terkel Radio Archive, which is managed by WFMT in partnership with the Chicago History Museum. A very special thank-you to Allison Schein Holmes, Director of Media Archives at WTTW/Chicago PBS and WFMT Chicago, for giving us access to Studs Terkel’s treasure trove of interviews. You can find many of them at studsterkel.wfmt.com.

This episode featured the songs “Southern Home” and “Ode to a Gym Teacher,” written and performed by Meg Christian, courtesy of Thumbelina Music and Shambhavic Recordings. “Leaping Lesbians” was written by Sue Fink and performed by Meg Christian, courtesy of Terre Music and Shambhavic Recordings.

This podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, the Calamus Foundation, proud Chicagoans Barbara Levy Kipper and Irwin and Andra Press, and our listeners, including Eileen and Tad Smith, Amy Quispe, and Brad Prunty on behalf of his husband and pioneering activist Tony Russo. Thanks, Eileen and Tad! Thanks, Amy! Thanks, Brad!

In case you’ve just recently started listening to Making Gay History, while we’re working on our next season, I suggest having a listen to some of our previous episodes from the past four years. You’ll find them at makinggayhistory.com, along with archival photos and additional resources. Or, you can listen to Making Gay History wherever you get your podcasts.

If you’d like to be the first to know what we’ve got coming up next, go to makinggayhistory.com and sign up for our newsletter.

So long. Until the next season of Making Gay History.

———

Song Credits

”Leaping Lesbians”

Written by Sue Fink

Performed by Meg Christian

Courtesy of Terre Music and Shambhavic Recordings

Used by permission; all rights reserved

“Ode to a Gym Teacher”

Written and performed by Meg Christian

Courtesy of Thumbelina Music and Shambhavic Recordings

Used by permission; all rights reserved

“Southern Home”

Written and performed by Meg Christian

Courtesy of Thumbelina Music and Shambhavic Recordings

Used by permission; all rights reserved

###