Lucy Salani

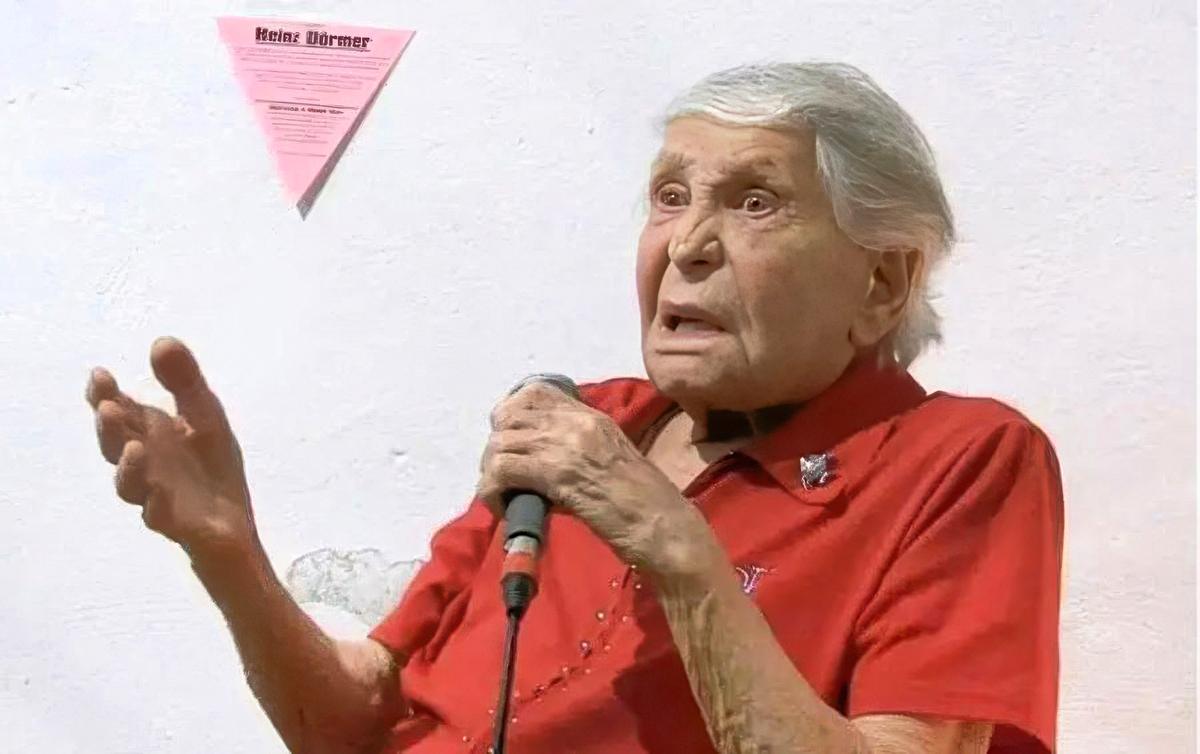

Film still of Lucy Salani, aged 95, from the 2021 documentary "C'è un soffio di vita soltanto" ("A Breath of Life") directed by Matteo Botrugno and Daniele Coluccini. Credit: Blue Mirror and Kimerafilm.

Film still of Lucy Salani, aged 95, from the 2021 documentary "C'è un soffio di vita soltanto" ("A Breath of Life") directed by Matteo Botrugno and Daniele Coluccini. Credit: Blue Mirror and Kimerafilm.

Episode Notes

Lucy Salani was assigned male at birth, so when she came of age she was conscripted into the Italian army. She soon deserted—the first of several daring escapes that eventually landed her in Dachau.

She’s one of the only trans people to testify about their experiences in Nazi concentration camps.

Episode first published March 13, 2025.

———

Audio Source

Lucy Salani interview footage courtesy of Matteo Botrugno and Daniele Coluccini, directors of the 2021 documentary C’è un soffio di vita soltanto (A Breath of Life). The film was produced and released in Italy by Blue Mirror and Kimerafilm and distributed internationally by True Colours.

———

Resources

Some of the websites linked below are in Italian, but internet browsers like Chrome allow you to access them in English translation. For general background information about events, people, places, and more related to the Nazi regime, WWII, and the Holocaust, consult the online Holocaust Encyclopedia of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM).

- For a brief overview of Lucy Salani’s life, read this biographical essay from A Gender Variance Who’s Who.

- Watch the trailer of the 2021 documentary C’è un soffio di vita soltanto (A Breath of Life), from which the episode’s audio was drawn, here. A Q&A with the filmmakers Matteo Botrugno and Daniele Coluccini is available here (CRASSH Cambridge/YouTube).

- An earlier documentary about Salani titled Essere Lucy (Being Lucy) can be streamed via GuideDoc and has a wealth of archival photos from throughout Salani’s life. The film’s director, Gabriella Romano, also wrote the biography that first introduced Salani’s story to the world. Italian readers can find the book, Il mio nome è Lucy (My Name Is Lucy), here (Donzelli Editore, 2009).

———

Episode Transcript

Lucy Salani VO: Ah, when I was young… It was all a party then, from morning to night. Laughing, laughing, and just having fun. We didn’t think of anything else.

———

Eric Marcus Narration: It’s 2019. Lucy Salani is 95 years old. She’s in her bedroom in Bologna, Italy, showing off the wardrobe from her 1950s cabaret act. She reaches into the closet for a sequined jacket with an ostrich feather collar, pulls it on over her zippered sweatshirt, and briefly strikes a pose.

———

LS VO: Now I’ll show you the last dress I wore on stage. This one I used to wear when I did my act. This one here. This is the dress.

This one reminds me of the last number I did in this dress. I did a beautiful number in this. I played the Miss. It was gorgeous.

When I went out, people would say I was a beautiful woman. But unfortunately now there’s just remnants. Everything passes, everything passes. Nothing gets renewed, nothing. Only the memory remains. Oh well. But when I see this dress, many things come to mind. Everything I’ve been through in my life, in that moment.

———

EM Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History: The Nazi Era.

Lucy Salani was born into a Catholic working-class family in northwest Italy in 1924, during the early years of Benito Mussolini’s dictatorship. She was raised in an anti-fascist household along with two older brothers.

Lucy is one of the only transgender people to testify about their experiences in Nazi concentration camps.

———

LS VO: My original name is Salani Luciano. But in my life I’ve taken many names. I was born in Fossano, in the province of Cuneo. Even when I was little, I looked like a girl. People would say to my mother, “What a beautiful little girl!” And my mother would say, “It’s a boy, it’s not a little girl.”

When I was a small child, I liked to do what my mother did. I imitated her in the kitchen, going grocery shopping, doing all those feminine things. Outside the house, too, I liked being with girls, not boys. I didn’t like boys because they made fun of me.

My life started badly. A painter lived in the apartment below us. He asked my parents if he could use me as a model: “Lend me the child so I can paint him!” My mother told me to go downstairs, the gentleman would make me a nice gift. He made me a gift alright.

This dear gentleman, he didn’t just want to paint, he wanted to do something more. He said, “Put your hands here, do this, do that.” It was a scary thing, I was afraid. He said, “Come, I’ll give you a present.” I was five years old.

I was naturally sexless until seven, eight years old. But after that I asked myself, how could I be so different from others? Sometimes I tried to be masculine but I just couldn’t do it. I would come home and say, “Mom, I’m female, I’m not male.” She’d say, “Are you crazy?” My brothers started teasing me. I became the laughing stock of my house.

Then, I had to start taking communion. They sent me to study the catechism. At some point, the priest wanted the same thing as the painter. And so it went. Everyone “gave me” something. And they told me, “Be quiet, don’t talk about it.” Every now and then they would send for me, or I would go to them voluntarily—because they gave me money! So I had clients at that age. I went to the cinema, I bought myself candy.

At some point my parents asked, “Where are you getting this money?” I explained the whole thing and all hell broke loose. My father got a job transfer and we moved to Bologna where he worked at the juvenile prison on Via del Pratello.

Later on, he got in trouble for helping inmates smuggle letters out of the prison. They sent him away to the border. My mother was left alone with three children. Every night she worked at a hospice for the elderly, and during the day she took in washing.

When I was 15, I found a job as a waiter in the center of the city. But then the lady who owned the restaurant called my mother and said, “Look, I don’t know what to do with your son because everyone says he’s a faggot, and I don’t like that, so I’m sorry but I can’t keep him on.” They fired me.

I got another job in a small shop where they worked on tires. They had lots of machines, and I liked it. But one morning my hand got stuck in the machinery. I lost half a finger. I stopped going in because I thought sooner or later something else would happen to me. So that didn’t work out either. I also worked for a baker, but that was a really tough life.

One evening, I was out walking and I passed near the church. There were three or four guys who had the same kind of feminine bearing as me—and I thought I was the only one in the world! I approached them and they said, “Look, a new one!”

It was a pick-up spot. In the evening, customers would arrive, and we would do things for money. We were all kids—15, 16 years old, 17. I thought, why should I go to work at a job if I can make money like this?

From then on, I was always with them, and they introduced me to this world. When we made a little money, we went partying. We went looking for guys. We went looking for guys, and we found them. We found some good ones and some not. Sometimes there were fascists and we weren’t welcome.

One time, on Via Indipendenza, I was walking with a friend who was sashaying. It’s not like he was doing it on purpose; it was his natural way of walking. But people were annoyed by it. I said, “Come on, put your hands down, don’t move like that!” A group of fascists noticed us and told us to follow them. I took off, but my friend went with them. They beat him up. They put tar up his ass. He was all full of tar.

Another time, that same gang found me alone and slapped me around. I wasn’t doing anything bad, just walking. You had to be very careful because these kinds of “adventures” happened a lot—people were always out to get you.

I was approaching the age when I would be drafted for military service. I showed up for the medical visit and said, “I’m a homosexual, I can’t be in the military.” “Ha,” they said, “that’s what everyone claims! It’s fine!”

They sent me to a base to work with artillery. In the mornings they taught us to shoot, which I detested. I was always trying to get assigned to office duty. I kept saying to the captain, “But I’m not made for this!” I hadn’t even done a month of military service when September 8 came. The barracks emptied out and everyone ran away.

———

EM Narration: On July 25, 1943, the Italian government ousted Mussolini. Six weeks later they surrendered to the Allied forces. Many Italian soldiers, including Lucy, abandoned their posts. But the Nazis still controlled northern Italy and Lucy was soon arrested and conscripted into the German army. When she was admitted to a military hospital with bronchitis, she slipped out and deserted again.

———

LS VO: I was still a German soldier, basically, since I’d escaped from the German army. I came back to Bologna. I found my old friends. They said, “Come, come. Now there are Germans who come to us, and they pay well!”

A German captain took me to the Hotel Bologna. There was a raid on the hotel. They let the German officer go but detained me. They found out everything. They tried me as a deserter of the German army—I was condemned to death by firing squad. I asked for a pardon, and they told me I would be pardoned in exchange for forced labor in Germany.

I arrived by train in Austria and they took me to a prison in Bernau, where I waited for my work assignment. They took me to a long warehouse filled with workers from all over the world, all prisoners like me. We manufactured parts for V-2 rockets, the ones that were dropped on London. We had to carry big pieces of iron, and I wasn’t able to do it.

I had to escape, but in the morning when they took us out of the barracks, they counted us. When we arrived at the worksite, they counted us. When we left there, they counted us. Going back into the barracks, they counted us. The barracks were surrounded by an electrified fence.

I made a plan with another guy. We used blankets to make a hole in the fence. Later, when we left work, this boy and I climbed through. We barely took 10 steps before the alarm started blaring. We ran on some train tracks to a small station, and found a spot under a train where you could lie down, above where the wheels were. The boy got in front, I was behind. The train was loaded up with coal, then it left. We were underneath it and disappeared.

The train pulled into a small station. We waited to hear something over the loudspeakers, to see if a train was going towards Innsbruck, because to get to Italy, we had to pass through there. We waited and waited and then decided to go with the first train that was leaving.

We stayed down in the undercarriage and arrived in a city with a big river, Hungary on one side and Austria on the other. There was a warehouse full of Italian workers, but they weren’t prisoners. They were free. We slipped in among them. They shared some food with us. We looked pitiful from all the dust underneath the train. We’d become like chimney sweeps, all black. Even pigs would have been disgusted. They cleaned us up and gave us clothes. They helped us, but we didn’t stay long because we would have gotten them into trouble.

We went back to the train station. Everything was bombed out and the signs were gone, so we hopped under the first train that was leaving. This train never stopped! We traveled almost an entire day underneath.

When it stopped, we were in the countryside. At first there were people around. We could only see their legs, so we waited until we didn’t see any more legs and we didn’t hear any more chatter. We peeked out. There was a sign. We had gotten under the wrong train! We were 15 kilometers from Berlin!

What to do? Luckily, we found a nice German fellow. He was obviously gay, this guy. He wanted to go to bed with us. Given the situation we were in, what could we do? It was the very last thing on my mind. In the morning he gave us breakfast and then—bam—we ran away. We got under a train again, took the first one we found.

At some point in the journey, the other boy said, “My hands are frozen, I can’t take it anymore.” He said, “At the first stop, I’m going up.” I said, “Don’t go up. You know the military’s up there, the guards.” I told him I was staying put.

At the next station, the train stopped. He went up. I don’t know what he did up there. The train started again and then it came to a halt. They must have pulled an emergency brake or something. I saw him running in the middle of a field. There was—pow! pow! They killed him right in the middle of the field. Poor boy.

I got out at the next stop. I felt like I was dying of hunger. It was almost Christmas. I saw someone loading packages onto the train, probably Christmas presents. When his back was turned, I grabbed a package. There was some kirsch in it, a bottle of alcohol. A cake. And some dried fruit. So I satisfied my hunger and found a toolshed to sleep in overnight.

But a man came and grabbed me and handed me over to the police. I said that I’d come from Italy and that I was lost, that I’d lost my unit. I gave a fake name—Sala Lucio. After beating me, they threw me in a prison that was so full you couldn’t even sit down. There were all kinds of people in there, 15 or 20 people in a very small room. In the morning they took us out, loaded us onto a freight train, and unloaded us in Dachau.

I saw an avenue with all these barracks, one after another. We went in. They made us strip naked. Someone came with a bucket and a brush. That was the disinfection. They walked by you and swiped you with this brush. It was a terrible burning feeling on my skin, like my skin was coming away, which it did the following morning. They gave us some old clothes, full of lice—full of them! So full there were nests in there, a hive. How disgusting!

They give us a number. I was 15504. Then they threw us into the barracks. The barracks had a round sink with spigots to wash ourselves. But in the morning it was completely iced over. We had to break the ice before washing.

The first day they assigned us a job. You couldn’t just be there in exchange for nothing, you had to earn it! They gave you a small tin bowl, and a piece of bread at lunchtime.

My first job was to take out the people who had died in the barracks overnight, and line up their corpses outside. Every day there were three, four, or five of them. They were replaced by new people. I brought the corpses to the crematorium, where they burned the dead.

There were so many, we just threw them on the ground, there was no other way. One morning I saw—not in my cart, but in the next cart—I saw a hand moving. I said, “Look, that one’s alive!” They said, “Ja, he has to die anyway. It’s time to die.” They threw him in alive. They burned him alive.

I couldn’t wait to stop this horrifying work. One day a guard asked for people to go work in Munich, laying train tracks. I said yes, and the next day we set off.

The Munich train station was a bombed out mess. A disaster. We had to remove the old pieces of train track and put in new ones. I preferred that to what I was doing before.

We were surrounded by guards, there was no way to escape. There was a guard who would take a piece of white bread, cut off a slice, remove the crust, and put the butter on, right in front of us—we who were so hungry. Then he would take the crust of the bread, and toss it next to him. One guy, I think he was Polish, he got up from his work and threw himself at the crusts and put them in his mouth. The guard was holding his bread knife. Luckily the guy turned or he would have been gutted. Instead the guard stabbed him in his buttcheek. So much blood… And the guard started laughing. The cut got infected, but the guy still had to come to work.

There was a bomb shelter nearby, and when bombs dropped overhead, we would go down into the bunker. When it was over, we would go back up to find that all the work we had done was destroyed. So we had to do it over again. We were half dead.

I had been in Dachau for a few months. And then one morning they took roll call and loaded us onto the train to head for Munich as always. But a few minutes later, an English plane strafed us with machine-gun fire. The train reversed and returned to camp. We were let off and suddenly all the guards were running away.

Everyone was trying to escape. There were machine gun turrets above the camp, and guards started shooting at us from above. Many got away, but if you were in the middle of the pack, how could you escape with everyone around you? Two or three people were killed near me. I got hit in the leg and went down. I passed out and I was down among the corpses. After that, I felt nothing.

I woke up on a cot. I opened my eyes and saw a row of cots with sick people. I thought, “How strange heaven is.” I was convinced I was dead, that I was in heaven.

The Americans had come. I had been out for three days like a dead person. They took care of me. After 15 days I wanted to go home but they wouldn’t let me. One morning a truck was leaving for Italy and I got the boys who were loading the truck to hide me inside, and I left. So I tricked the Americans, too.

When I got to Italy, I felt like I was dreaming. Being back in the world was a liberation. I went into my house. My mother, my father, my brothers were all there. They were shocked because the newspaper had reported that I was shot for deserting the German army. When I saw my parents I said, this is a dream, because it all seemed like an illusion.

After the war, I fell in love with an Englishman from Manchester. His name was Tony Flannery. I will always remember him. He was a handsome boy with a mustache. A really handsome boy. He was wonderful.

I brought him to stay at our house and introduced him as my boyfriend. When I brought boyfriends home, my parents would start laughing. They’d say, “Sure, let’s call them boyfriends.” Tony slept in my room and one night my mother came in and he was all over me. Ohhh, she was angry. Then Tony was arrested for stealing tires, poor boy.

———

EM Narration: Lucy was living in her family’s Bologna apartment and had returned to sex work. In the 1950s, she developed a cabaret act inspired by her idol Marilyn Monroe, and gave performances in Paris and across Italy.

———

LS VO: It was a striptease, but it was comedic—I did it to make people laugh. I would dance and then I’d remove this and then that, and then I was just in a slip and a bra. Afterward, when we went out, there was always an admirer who invited you to dinner. And not only dinner—they also wanted something else. Ah well…

I’d find people who were married and everything, and they’d say, “Well, a wife gives you children, she gives you affection, but real sex, that’s what you give me.”

When I met men, they were convinced I was a woman. I had a little wig of blond hair and I stuck it down there so you couldn’t see anything. I had such a tiny little thing anyway. They made love to me and that was that. Unless they put their hands down there. Then I’d say, “Go touch your wife, not me!”

At some point, my brothers complained. We were all living at home, sharing a bedroom. They kept insulting me: “You’re the shame of the family, the family scandal,” that kind of thing. My mother was the go-between. I didn’t really talk to my father. One night we had a disagreement and I decided to leave.

I made my own life. I went to Turin, slept in the car, looked for a job. In the evenings I went for my walks. There were these gardens there, Parco del Valentino. I sat there and found a guy every now and then. Sometimes I fell in love, sometimes I didn’t.

When I went to visit my parents, I would dress as a man. Otherwise, I was against dressing as a man. My name, I didn’t change it. I was still Salani Luciano. I could have changed it, but I thought, if my parents gave me this name, why should I change it? I am Luciano and I will stay Luciano. Lucy was always my nickname. But I am Luciano.

———

EM Narration: For more than two decades, Lucy lived in Turin where she continued her sex work and became a highly sought-after upholsterer—a trade she learned from a longtime lover. When her father died she went back to Bologna to be with her mother. Her sex work helped to pay for her mother’s nurse.

Lucy was in her 60s when two younger friends went to London for gender reassignment surgery. They persuaded Lucy to join them and undergo the procedure as well.

———

LS VO: When they started the operation on me, they said it wouldn’t go very well because there’s not enough material. They said the scrotum has to be big enough to do a good job, and I didn’t have anything there.

My body is not masculine, it’s feminine. See, when I was born, the doctor thought I was a girl. Because there was nothing there. Then when they washed me, the little penis came out.

After the surgery, I did have sex a few times, but I couldn’t stand it. I don’t feel anything anymore. I can feel affection, but there’s no sensation down there anymore.

Thank goodness I was already quite old when I had the surgery, so I didn’t lose out on much. The other two were young. But they were very satisfied with the operation. It depends on how a person thinks about it. Because they were all, “Now we are women.” It meant a lot to them. And I’d say, “Maybe you look like a woman, but what can you feel?” They’d say, “Well, sure, before I used to come all over the place, I used to feel such pleasure…” And I’d say, “Oh, so you remember that! See? You remember!” “But I’m a female.” It meant something to them.

They gave you a test after the operation to convince you that now you’re female. And I said, “I was already born female, there’s no point in giving me a test.”

———

EM Narration: In 2009, Lucy shared her story publicly for the first time in a biography by Gabriella Romano. When Lucy was in her 90s, she became the subject of A Breath of Life, a documentary by Matteo Botrugno and Daniele Coluccini. At the end of the film, Lucy returns to Dachau for the 75th anniversary of the camp’s liberation. She was one of more than 200 thousand people who were imprisoned there between 1933 and the end of the war. Tens of thousands of them—including Jews, communists, Roma, and gay men—were murdered or died of starvation and disease at Dachau.

———

LS VO: When I talk about these things, it still makes me cry. Sometimes I feel like I’m still there. Sometimes it happens to me in bed—I have a flashback. In the morning I find I’ve been crying in my sleep. The pillow is all wet. I’m not even aware of it, but my dreams show that I’m still there.

———

EM Narration: Lucy Salani died in Bologna in the spring of 2023. She was 98.

———

Coming up next: Margot Heuman, a German Jewish lesbian whose love for another girl sustained her during the years she spent in concentration camps.

———

This episode was produced by Nahanni Rous, Inge De Taeye, and me, Eric Marcus. Our audio mixer was Anne Pope. The English voiceover was provided by Bianca Leigh, the translation by Carlotta Brentan and Nahanni Rous. Our studio engineers were Michael Bognar and Charles de Montebello at CDM Sound Studios. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Thank you to our photo editor Michael Green, our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham, and our founding production partner, Jenna Weiss-Berman at Pineapple Street Studios.

The testimony you heard in this episode came to us courtesy of filmmakers Matteo Botrugno and Daniele Coluccini. Their film about Lucy is called C’è un soffio di vita soltanto, or A Breath of Life. It was produced and released in Italy in 2021 by Blue Mirror and Kimerafilm and distributed internationally by True Colours. We are grateful for their generosity in sharing their footage with us.

To learn more about the people and stories featured in our episodes, please visit makinggayhistory.org, where you’ll find links to additional information and archival photos, as well as full transcripts.

This special series on the experiences of LGBTQ people during the rise of the Nazi regime, World War II, and the Holocaust is a production of Making Gay History, in partnership with the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale University.

I’m Eric Marcus. Until next time.

###