“Les-Lee”

Les-Lee at Le Carrousel, mid-1950s. Credit: Photo by Daniel Frasnay (Galerie Berthet-Aittouarès) from the 1956 book “Paris by Night.”

Les-Lee at Le Carrousel, mid-1950s. Credit: Photo by Daniel Frasnay (Galerie Berthet-Aittouarès) from the 1956 book “Paris by Night.”Episode Notes

During a career that spanned more than three decades, Canadian female impersonator John Falk Tomkinson appeared around the globe under the stage name Les-Lee. In 1967 Studs Terkel sat down with the performer to talk about his art and upbringing, and his experiences of being “different.”

Episode first published October 29, 2020.

———

John Falk Tomkinson, better known under the stage name Les-Lee, was born in Canada in 1929. He was raised in Montreal and later on a farm in Quebec’s Eastern Townships. At 18, he moved to New York City, where he began his career as a female impersonator at the 181 Club. Read about the 181 Club here.

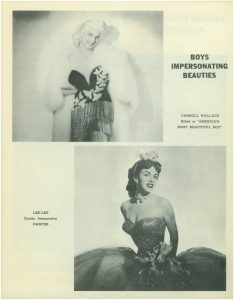

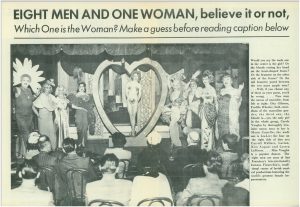

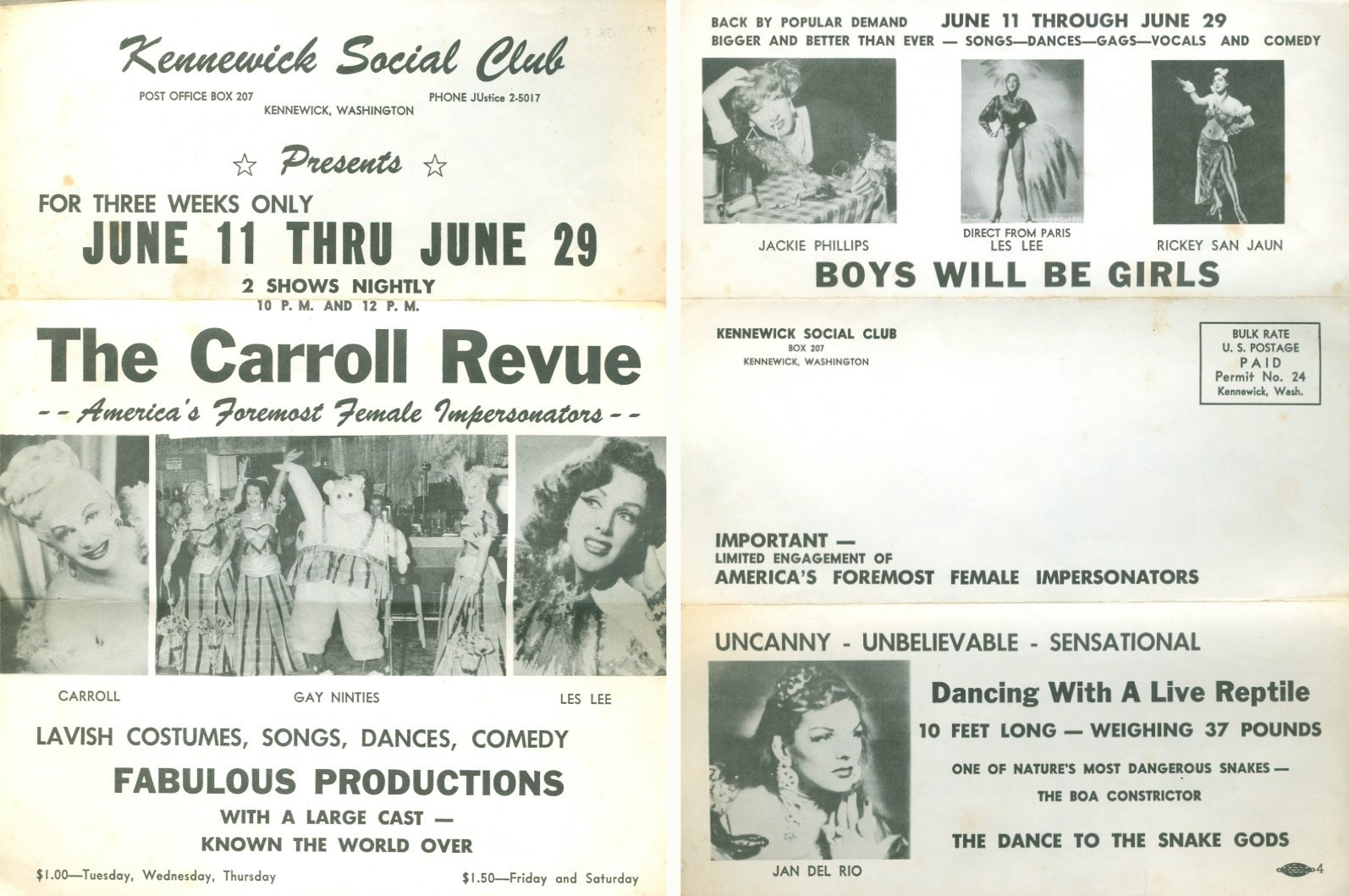

At the start of the 1950s, Les-Lee moved to San Francisco, where he worked at the legendary drag venue Finocchio’s. The image below shows Les-Lee in a 1953 Finocchio’s program; you can find the entire program here. See more ephemera from Finocchio’s here and read about the club’s history here (starting on page 44 of the PDF).

In 1955, Les-Lee moved to Paris and started performing at Le Carrousel. Learn about the venue’s history and see Les-Lee in Le Carrousel’s programs here and here.

At Le Carrousel, Les-Lee worked alongside British trans icon April Ashley, who wrote about Les-Lee in her autobiography, April Ashley’s Odyssey. Treat yourself to this video of Ashley narrating a slideshow from a 2013 exhibition about her life.

In 1963, Les-Lee made a brief appearance in the French film Dragées au Poivre (translated as Sweet and Sour). You can read about his scene in this review (under the heading “Father! Daughter!”).

In 1970, Les-Lee appeared in Paul Raymond’s “Birds of a Feather” revue at the Royalty Theatre in London. You can see the program here. And here, in the top left corner, is Les-Lee at the 1973 Cannes Film Festival, identified as a headliner at a “posh female impersonation club.”

In the interview, Studs Terkel mentions the famous female impersonator and Hollywood star Julian Eltinge. To learn more about Eltinge, read this article about his career, see him perform in this brief clip, or watch this documentary about his life and work.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus, and this is Making Gay History.

This season we’re reaching beyond my own collection of interviews to bring you voices from the Studs Terkel Radio Archive. The archive holds more than 5,000 programs that the pioneering oral historian and broadcast legend recorded for WFMT radio in Chicago between 1952 and 1997.

Studs conducted most of his interviews at his studio in downtown Chicago. But in late 1967 he took his tape recorder to Paris. That’s where he interviewed female impersonator John Falk Tomkinson—a 38-year-old Quebec native who performed under the stage name Les-Lee.

Les, as he was known to his friends, began his career in the late 1940s at the Mafia-controlled 181 Club in New York’s East Village. It was known at the time as “the homosexual Copacabana.” In the ’50s, he took the stage at legendary venues like Leon and Eddie’s in Miami, Finocchio’s in San Francisco, and Le Carrousel in Paris. But wherever he performed, as an exotic interpretive dancer or as a singer, he was always dressed to perfection in dazzling costumes that he designed and sewed himself.

In the ’60s, Les starred at Chez Les-Lee—his very own club on rue Guisarde in Paris’s Saint-Germain-des-Prés neighborhood. That’s where Studs sat down with him for an interview first broadcast on New Year’s Eve 1967.

So let’s join Studs Terkel and Les-Lee, and a room full of raucous patrons, as Les, the proud host, begins by sharing a bit of his club’s ghoulish history.

———

Les-Lee: Actually, the place was called the Guisard before because it was the stable of the Duc de Guisard, and which… Actually, this beam, this, right above your head, is where he was hung.

Studs Terkel: Oh, there’s some history then.

LL: Yes.

ST: Sort of macabre history.

LL: Exactly. That’s why they, they, the, the, we know that they couldn’t pull, pull the building down, even if they wanted to, because it’s a, a point of history, and all points of history in Paris are not allowed to be changed.

ST: Now, you, you yourself are not French.

LL: No, I’m not. I’m Montreal boy from, uh, Montreal, Canada. And I’ve been in Paris for seven years now.

ST: What led you to Paris?

Les-Lee: Well, actually, my, my business, I, I’m a female impersonator. I worked in New York and, uh, I was working in Finocchio’s in San Francisco at the time, and a, a manager of one of the big shows here in Paris saw me working and asked me to come to Paris, and it amused me so I came and I haven’t, I haven’t been back since.

ST: Well, thinking of this craft or this art or skill of female impersonation, I remember as a small boy, I saw someone named Julian Eltinge years ago—

LL: He was the first actually.

ST: He was the first.

LL: He was the first in America who ever became a big star. He did, uh, silent movies with Gloria Swanson and—

ST: Well, the, the technique, the theme of female impersonation itself has—

LL: … has changed a great deal, especially in Europe, because the female impersonators in Europe, they, they are not like the female impersonators in America nor of the tack of Julian Eltinge of being as a boy in the daytime and a, and a female impersonator impersonating at night. The female impersonator in Europe have gone to the extent of taking female and hormone injections…

ST: Oh, really?

LL: … and growing their own hair and living as women, which I don’t approve of. I don’t think… They’re neither one or the other at that point.

Meet-Les-Lee-Campaign-n.7-March-1976-p.28Interview “Meet Les Lee…” in the Australian publication Campaign, no. 7 (March 1976), page 28. Credit: Courtesy of the Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives.

ST: Well, let me, I didn’t realize this, that there is this difference.

LL: Oh, a big difference.

ST: Between the American female…

LL: Oh, a big difference.

ST: … who leads a split life, sort of…

LL: It’s not a split life. It’s, it’s like any, any entertainer, actually. I mean, a, a clown is a clown at, while he’s in the circus…

ST: I see.

LL: … and a personality of his own at, in the daytime.

ST: He does not become a clown in real life. Now your tech— Now, what is your, your interpretation? You, you believe in the American interpretation?

LL: Oh, I certainly do. I, I think that’s the whole art of being a female impersonator. I mean, there is people who know me and have seen me as a female impersonator who I’ve passed on the street the day after and not knowing me at all.

ST: So here then is the skill, the art. Are there particular…?

LL: Yeah, not knowing at all.

ST: We think of female impersonation, we think of many who, who impersonate celebrated figures, actresses or…

LL: Yes.

ST: … people in social— Do you, do you have certain targets?

LL: No, I, no, I do not. I, I have my own personality, which I, I push forward and, and jokes. And I, I sing in my own natural voice. I don’t try to make anything artificial about it. The, the art of my work is just looking something different than what I am.

ST: And this is the art of illusion, is it not?

LL: Exactly.

ST: It’s the art of illusion.

LL: Of illusion.

ST: You say you sing in your natural voice.

LL: Yeah.

ST: And yet you are female imper— So this then, because of illusion, would come through as a contralto perhaps.

LL: No, a tenor, a male tenor voice.

ST: Oh, a, a male tenor voice.

LL: A male tenor voice, but the illusion of seeing me as a girl, it becomes more feminine.

ST: That’s what I mean, you’re—

LL: It’s your eye, your eyes doing tricks with you.

ST: Here’s the matter of illusion at work.

LL: Exactly.

ST: So it’s a question of it being an art and a skill with you rather than a way of life.

LL: Exactly.

ST: Well, this, the place itself, of which you’re the host, the Chez Les-Lee. We should point out, the food, the menu, looks most enticing indeed. Do you have a certain way, uh, you’ve chosen…?

LL: We, we have tried to keep the food somewhat, uh, French home cooking because the French cuisine in Paris is very, very highly seasoned and lots of wine and very fancy and very heavy, actually. It’s the best cuisine in the world, they say, although, myself, I prefer a hamburger and a Coca-Cola. But, um, we try to keep it very simple and the, the old homemade bread and, something we’ve tried, kept to go with the atmosphere of the room because it’s all in, in old wood and, uh, just ordinary [inaudible] walls.

ST: Back to you again, Les-Lee. Why…? You’re a female impersonator. Why did you come to, why Paris? Are there more female impersonators here than there would be in other cities in the world?

LL: No, no, I don’t think so. But I think that the, the, uh, art of female impersonating in Europe is much more highly looked at than in America.

ST: It’s not regarded as freakish, say, as would be in America.

LL: Not at all. Not at all.

ST: And so this, in a sense, you feel more, perhaps, uh, more accepted?

LL: No. I mean, you’re accepted to an, to a point. If you’re an entertainer or an artist, they will look at you and respect you. I have very, very high respect here in Paris because everyone knows me as being a female impersonator. Like back home, if people know me of being a female impersonator, they sort of shun their noses and point.

ST: Yeah.

LL: Which doesn’t make any difference to me because they don’t pay my bills and I live my life. As long as I don’t hurt anyone and I have my family, who respect me, that’s the most important thing to me.

ST: In short, this is the point, I think it’s rather a key point you’re raising: here you’re not being pointed at in a rather derogatory manner.

LL: Not at all.

ST: And this would be the case back home?

LL: Oh, back home most certainly. Because I started in the business in New York at the 181 and, believe me, I know what kind of remarks people make in America.

ST: Is this what you’ve always wanted to do? When you were a small boy in Montreal, what was your dream, when you were a small boy?

LL: To be a fashion designer.

ST: Oh, to be a fashion designer.

LL: Yes.

ST: Well, then, uh, when did the idea of fashion designing occur to you? About how old were you?

LL: Oh, 17, 18 years old.

ST: At 17, 18.

LL: Then I went to art school in New York and then to America. And, uh, the place I was working to went bankrupt and I was very, very young. When I, when I left home I was 18 years old, and, uh, nobody would just give me any chance at all because I was so young. And I felt that if someone had given me a chance, I would have become a big designer.

ST: Were you an only child, by the way?

LL: No, no. I’m the youngest of four.

ST: You’re the youngest of four.

LL: Yeah. I came from a farm in Canada.

ST: Can you recall when you were very small, what your thoughts were, uh, what you wanted? Did you want to be an actor?

LL: No, not at all.

ST: No.

LL: If someone told me that I was going to be on the stage, I would have laughed at them. Not at all. And there’s nothing in the family at all like that. Nothing. I’m the only person who, in the family, who is artistic. Not that I want to continue in my work. I hope that one day that I’ll get out of it and go back to that little thought of being a designer.

ST: Do you have thoughts about designing? I mean, do you have a, a, something in your mind, a specific thing, say, in, in connection with fashion?

LL: I would like to do the eccentric things. But people won’t wear them so there’s no sense—

ST: What sort of eccentric things?

LL: Oh, eccentric accessories for men and women. I think the, the average person dressed for the Mrs. Smiths and the Mrs. Jones. If they would just dress for their own personalities, they’d be much happier.

ST: So you’re asking now—

LL: We do, we do. We dress for Mrs. Smith or Mrs. Jones. What would she say if I wore this? Or what would she say if I wore that? If we wore exactly what we thought we would feel good in and enjoy wearing, colors and …, I think people would be much more happy in the world.

ST: You’re one of four children, is that right?

LL: That’s right.

ST: You’re one of four children.

LL: The youngest of four. I have two brothers and a sister.

ST: One of the brothers, the older brother is a plumber, right?

LL: That’s right.

ST: The other a machinist.

LL: A machinist.

ST: And your sister?

LL: And my sister a housewife.

ST: A housewife.

LL: With two children.

ST: Now I’ve got to ask, how do your two brothers feel about you?

LL: My older brother, we don’t talk about. My, my brother next to me thinks that I’m a very fine entertainer and a very fine person because, uh, I live my life correct because of my mother and father.

ST: And your mother and father, they’ve seen you at work as a female impersonator?

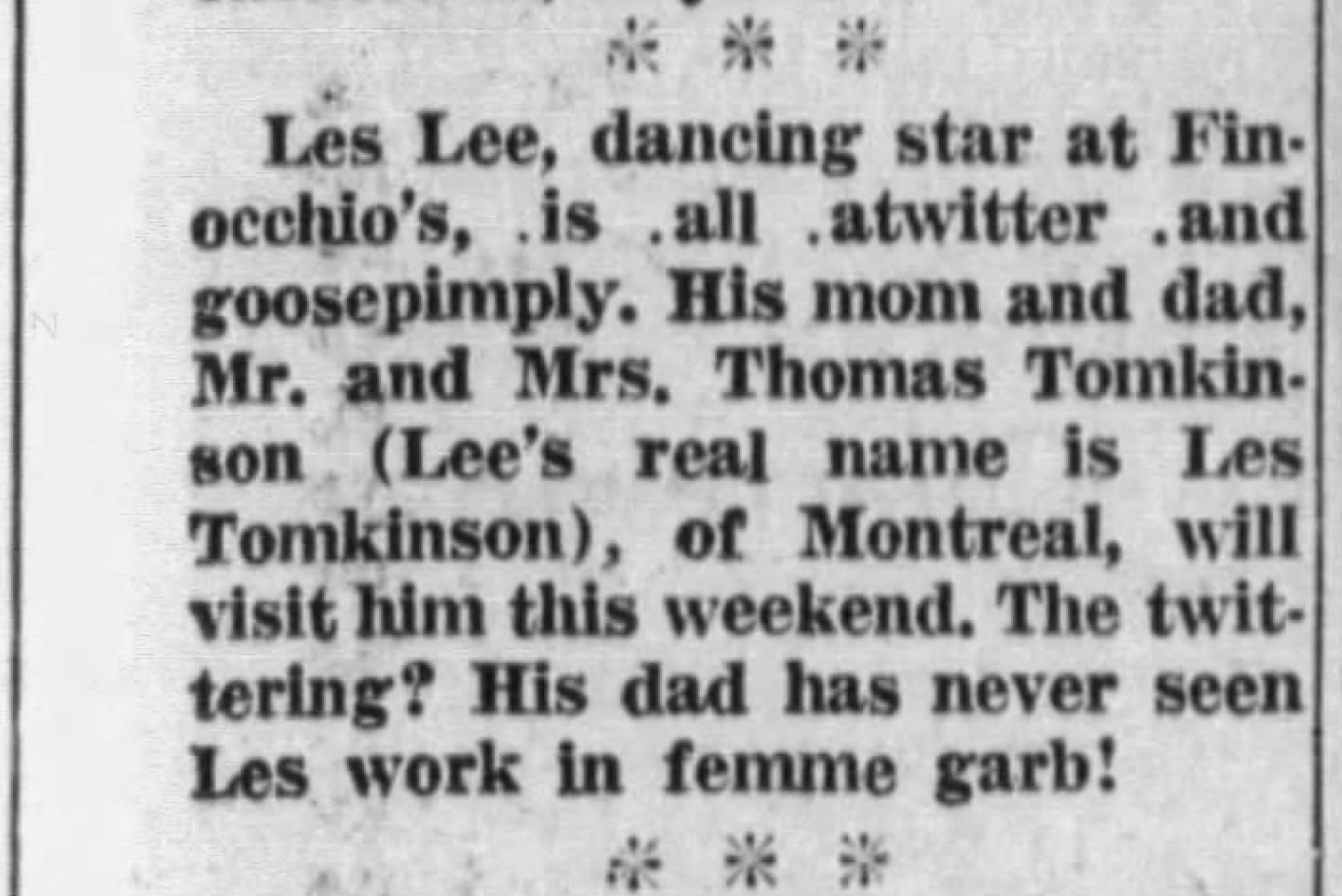

LL: Yes, they saw me working in San Francisco.

ST: What were their reactions?

LL: They drove across Canada for the first time in their lives, which is a wonderful drive, actually. And they, they saw me working on stage. My mother had always seen pictures of me and didn’t think very much of it. My father was completely against it until he saw me work. And then when he saw me work, he knew that, he saw in me the goodness and the point of being a good entertainer. And he was very pleased, very proud.

ST: You have friends… You have friends, you’ve told me, who never have told their parents.

LL: They would never think of telling their parents that they’re female impersonators because in America it’s shunned upon. Even though I was in America when I [inaudible], it wouldn’t be shunned upon because my mother and father don’t shun on things that their children do, because it’s done in a… They said, they said to me, “We taught you the right and wrong. And if you don’t do things right, the things that are wrong, it’s all we can teach you, there’s nothing more.”

ST: But they want you to be happy?

LL: Oh, they know that I’m happy. I write to her every, my mother and father, every week. And they write to me every week.

ST: You said, uh, you were different. You were different.

LL: Yes. Completely different to my brothers and sisters. That’s why I was, I was very alone as a child because I was different. And until I really found my, my life and found out how I felt in life, I was completely opposite to everything that was done in the family. And therefore I was alone as a child. But now I’m not at all.

ST: When, when did you—can you remember this, or is this too difficult—when you first felt you were different?

LL: Oh, all my life. All my life. As far as I can remember back.

ST: I know, uh, this is a difficult one to answer…

LL: No, it’s, it’s a different thing. It’s a very delicate situation to talk about, but it, the, my, I did things that my brothers didn’t enjoy doing. They—as I say, one is a plumber and the other’s a machinist—they, they would build things of wood and iron, and, uh, very hard, constructive things, where I would be painting or, or designing or, which is completely opposite to what they—

ST: You worked with softer fabrics…

LL: Softer fabrics.

ST: … perhaps silk and velvets.

LL: Exactly. Yeah.

ST: And always there in the beginning, this was your memory.

LL: Always, always, always. I was always very creative. I always… If my mother was giving a party, I was the one who did the table and made the decorations for the house and… If there was anything to paint or to draw or posters for the church, it was always, always me.

ST: You have early school memories? School?

LL: I hated school.

ST: You hated school.

LL: Hated school.

ST: Why?

LL: Because I was different from everyone else. I felt different. I don’t know whether I was different than everyone else, because I didn’t know everyone that was at school.

ST: Did the other kids, did they, uh, pick on you?

LL: Yes, because I was, I’m very fine-featured—I was when I was a child—and they picked on me, like all kids do, pick on everybody.

ST: Who is different.

LL: Who is different.

ST: Who is not like themselves.

LL: Who is different. Exactly.

LL: It’s a thing that a lot of people don’t understand with, with children. They don’t try to understand—which was, as I say, very fortunate, my mother and father did understand. But there are so many children and so many boys and girls in the world who are so far away from their families and their mothers and fathers because of this reason. They don’t want to understand. They just think, oh, it can’t happen to my child. My child is not different from anybody. But we are. Everyone is different. Everyone in the world is different.

ST: Have you ever talked about this with your friends here, who also female impersonate?

LL: No, I don’t.

ST: They never do, do they?

LL: No. I have no reason to talk of my private life to my friends here.

ST: They never, they never—

LL: Because I don’t think we have very many friends. People don’t have very many friends, really. When you really think how many friends you really have, really friends. We don’t have very many. I know thousands of people in, in Paris and London and America and Canada. And I think I have four friends. You can, you can have lots if you have the money. You can have money, but what’s money? Money can’t buy happiness nor health, or friends, really. You can buy artificial friends, if you want them. I’m a very, very big realist. I see things too clearly, I’m afraid, which has, which has made me happy because I see exactly what, what I have to live with. And I’ve lived with it.

ST: When did you find you could make your way? Despite—

LL: When I left home, when I was in New York, by myself. I left home when I was 18 years old and I went to New York with a scholarship as a dress designer. And I lost my job because of the, the, um, the company become bankrupt. And I worked in the automats, believe it or not, as a boy picking up dishes.

ST: Busboy.

LL: Busboy. And then I started working in show business as a skater at the Roxy Theatre. But I was alone, at home, but I was alone in New York. And I didn’t know anyone, so no one knew me or where I came from. So I felt that I would make my life as I choose and no one would bother me, which they didn’t. And I came right out of my shell. I really did. Because I knew that by hiding or by, by trying to be something that I’m not would become very artificial, and therefore I’m exactly as I am. I talk the way I please. I dress the way I please. And if people accept me, it’s because I am what I am and otherwise, otherwise they don’t and I don’t really care. Because to me they’re not people. Because I accept the people that come in here. I don’t know what they are or who they are or where they are, but they’re all very friendly with me.

———

EM Narration: Les closed his Paris club in the late 1960s, but continued to appear on stage for at least another decade. The ’70s brought engagements at the Birds of a Feather drag revue at London’s Royalty Theatre, a seven-year stint at a gay club in Cannes, and tours in Asia, Australia, and across continental Europe. His act—a little nice, plenty naughty—included impersonations of Marlene Dietrich, Judy Garland, and Josephine Baker.

les lee programProgram for Les-Lee’s “Showtime—One Man Show,” ca. mid-1970s. Credit: Photos by Peter Stille, Hamburg, Germany; program pages courtesy of Travestie Erinnerungen/Facebook.

After that, the digital trail of Les’s professional life runs cold. Information about his personal life, beyond what he told Studs, is even tougher to find. But the 1982 autobiography of early British trans advocate April Ashley offers some glimpses. April and Les met in Paris the second half of the 1950s, when they both performed at Le Carrousel.

April described Les as having “all the old-fashioned vices but all the old-fashioned virtues too,” noting that he sent money home to his parents every month. For a time they were roommates. April wrote, “I shared a big apartment with him and had hardly any sleep. There were troops of men through the flat all night long while I snuggled up to Frou-Frou, [his] dog, christened after the underskirt of a cancan dancer.”

John Falk Tomkinson, best known to fans the world over as Les-Lee, died in Paris on August 13, 2006. He was 76 years old.

———

Many thanks to everyone who makes Making Gay History possible: senior producer Nahanni Rous, co-producer and deputy director Inge De Taeye, audio engineer Kevin Seaman, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, genealogist Michael Leclerc, and our social media team, Cristiana Peña, Nick Porter, and Denio Lourenco. Special thanks to Jenna Weiss-Berman and our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Studios, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Season eight of this podcast is produced in association with the Studs Terkel Radio Archive, which is managed by WFMT in partnership with the Chicago History Museum. A very special thank-you to Allison Schein Holmes, Director of Media Archives at WTTW/Chicago PBS and WFMT Chicago, for giving us access to Studs Terkel’s treasure trove of interviews. You can find many of them at studsterkel.wfmt.com.

Season eight of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, proud Chicagoans Barbara Levy Kipper and Irwin and Andra Press, the Small Change Foundation, and our listeners, including Eric Lee and Joe Cangelosi. Thanks, Eric! Thanks, Joe!

Stay in touch with Making Gay History by signing up for our newsletter at makinggayhistory.com. Our website is also where you’ll find previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature.

So long! Until next time!

Drag artists Terry Durham, Les-Lee, Ricky Renee, Barry Scott, and Laurence Daury performing in Paul Raymond’s show “Birds of a Feather” at the Royalty Theatre, London, March 31, 1970. Credit: Photo by K. Britten/Fox Photos/Getty Images.

###