Kenneth Roman

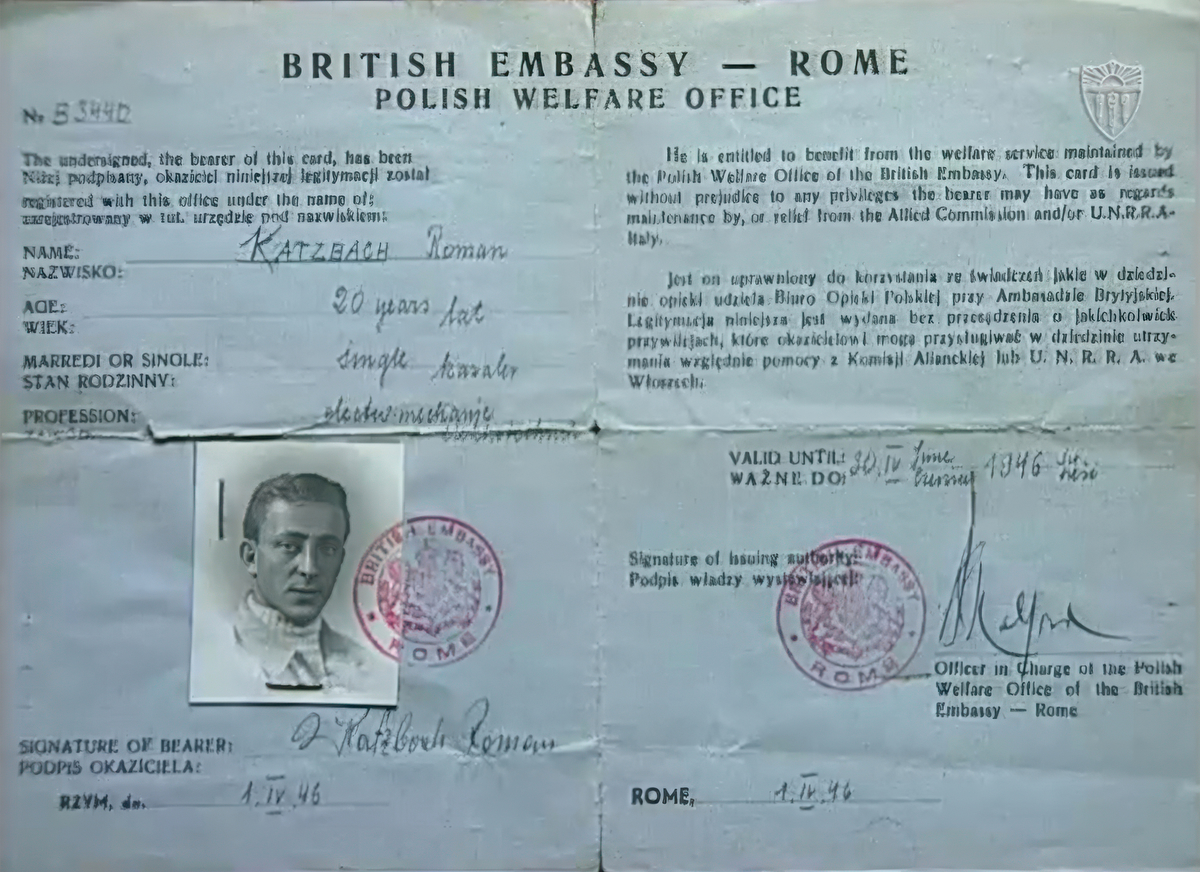

Kenneth Roman, ca. 1946. Photo included on an identification document displayed during Kenneth Roman’s USC Shoah Foundation interview conducted on June 1, 1998, London. Credit: USC Shoah Foundation.

Kenneth Roman, ca. 1946. Photo included on an identification document displayed during Kenneth Roman’s USC Shoah Foundation interview conducted on June 1, 1998, London. Credit: USC Shoah Foundation.Episode Notes

Kenneth Roman was 15 when the Nazis rolled into his Polish hometown. After they liquidated the Jewish ghetto to which he and his family had been confined, he was sent to a series of forced labor camps and finally a concentration camp, where a sadistic block elder made him his “batman.”

Episode first published March 27, 2025.

———

A note about Jimmy Draper:

Thanks to genealogist Adam Gelman, we’ve learned since the publication of the episode that Ken Roman’s partner, James Draper, died in late 2014.

———

Archival Audio Source

The interview with Kenneth Roman is from the archive of the USC Shoah Foundation – The Institute for Visual History and Education, © 1998 USC Shoah Foundation. For more information about the USC Shoah Foundation, go here.

———

Resources

For general background information about events, people, places, and more related to the Nazi regime, WWII, and the Holocaust, consult the online Holocaust Encyclopedia of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM).

- You can watch Kenneth Roman’s entire testimony on the USC Shoah Foundation website here (registration for their Visual History Archive is free).

- An earlier 1990 oral history with Roman was recorded by the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies; it resides here (create a free account with Fortunoff’s Aviary platform to view it online).

- The uniqueness of Roman’s on-camera appearance alongside his partner, Jimmy Draper, is one of the topics discussed in researcher Sarah Ernst’s presentation “Queer(ing) Holocaust Video Testimonies: Introductions, Explorations, and Reimaginings” (USC Dornsife Center for Advanced Genocide Research).

- Roman narrated his wartime experiences in his memoir Romek’s Lost Youth: The Story of a Boy Survivor; it was published posthumously in 2022 by Esther Ormianer, a distant Canadian cousin of Roman’s, who shared her memories of him here. (The book is out of print and was sold only to public and school libraries, but an occasional copy pops up online; we found one on eBay.)

Note: Ormianer states that Roman was 90 rather than 92 when he died. That discrepancy is due to the fact that, when the Gorlice ghetto was established, Roman’s identification papers were changed to say he was two years younger than he actually was to give him a better chance of avoiding being rounded up for forced labor.

———

Episode Transcript

Shirley Murgraff: Do you remember your first sight of, of German soldiers?

Kenneth Roman: Of course I do, very well. I was, I walked down the market square, saw them coming up on these motorcycles and sidecars with a, with a machine gun in front. And we, so we just stood on the pavement watching them come in.

It was a spectacle, that’s all. Ob—obviously it was my age. I mean, it was all excitement. And since at the time they weren’t beating or shooting anybody, it was not apparent, you know, what’s going to happen.

———

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History: The Nazi Era.

Kenneth Roman, originally Roman Katzbach, was born in 1924 in the southeastern Polish town of Gorlice. His mother died when he was a child and he was sent to live with his maternal grandfather, a religious Jew.

Ken’s grandfather owned a successful soda factory and Ken grew up in a large family mansion surrounded by dozens of uncles, aunts, and cousins. He recalled his childhood as prosperous, cultured, and idyllic.

Ken was 15 years old when the Germans occupied Gorlice in September 1939. Jews were soon banned from social and economic life, schools and synagogues were shut. Two years later, the Nazis confined Gorlice’s Jews, including Ken and his family, to a ghetto.

Decades later, when Ken was in his 70s and living in London, he shared his story with the USC Shoah Foundation. He told interviewer Shirley Murgraff about the Nazi commandeered sawmill in Gorlice, where he was hired as an electrician. The mill’s supervisor was a brutal antisemite, but for a time the job saved Ken from ending up in a labor camp. His luck ran out when the Nazis decided to liquidate the ghetto.

———

KR: The final action took place on August 14, 1942. On the ill-fated day, about four o’clock in the morning or five o’clock in the morning, the SS and the Storm Troopers arrived. And they encircled the ghetto compound, and they started hammering on every single door: “Aufmachen, aufmachen! Open, open!” Those doors which didn’t, which didn’t open quick enough were machine-gunned.

They were driving everybody into, into the market square—men, women, and children. And the um, then they were systematically searching every house. They were checking the basements, lofts, hidden rooms, panels.

My friend Joe Kosenik, where he was, there was a woman, uh, she was having trouble with her infant and she didn’t come out quick enough. So, um, they went into the house and they saw her there, and just be—and just because she wasn’t outside, so they shot her. And, and they grabbed the child out of her hand and threw her out of, well, some threw it out of the window onto the pavement.

SM: How prepared were you for this action and—

KR: None. I wasn’t at all. There wasn’t like another things where there was, uh, what they call, um, a deportation, where everybody packed their suitcases, and… I mean, that was—nobody had an idea. It was secretive and it was done without any warning.

So when we were finally sort of driven out, there were Poles kept coming up, I mean, to the SS and the Gestapo saying where Jews were hiding.

SM: What happened when you got to the square?

KR: Well, once we got to the square, we were just standing there not knowing what’s going to happen. Then there was a bit of a tumult; uh, the, uh, the headman, Kreuzer, arrived in his car demanding, uh, from the Gestapo his workers. So they selected 60 of us, including myself and Joe Kosenik.

SM: Approximately how many people do you think were assembled in the square at this time?

KR: Oh, God. There must have been, I don’t know, a thousand or more. So, um, so we were picked out. Uh, then they picked out all the old and sick on, on a separate group. And then all the others were marched to the railway station.

The whole thing was so traumatic. There am I, for the first time in my life, left on my own. Nobody to give me food, nobody to look after me, no clothing, nothing. Just… It was beyond comprehension.

SM: Were you able to say goodbye to your family?

KR: No. You couldn’t wave, you couldn’t do anything. You were petrified. You didn’t know what’s happening, you know, with all the SS with machine guns around you.

SM: Did you see the, the other people, the women and the children and the other people?

KR: No. What happened, they, they, the 60 of us, they took us to the sawmill. They created a little camp with two or three barracks, whatever. And they had SS guards around it so that nobody escaped.

But what we heard was that the old and the sick were taken to a disused brickwork, and that was not far away from the sawmill. And there they shot them all. We could hear, we could hear the shootings.

SM: And what happened to the others who went to the railway station?

KR: They all dispersed—Plaszow, Auschwitz, uh, Treblinka—God knows. And nobody else knew where they went.

———

EM Narration: Ken, his friend Joe, and the other workers were imprisoned at the sawmill for a few months before the Nazis transferred them to a series of forced labor camps. In August 1944, they were taken by cattle car from Poland to the Flossenbürg concentration camp in Germany, near the Czech border.

Flossenbürg originally housed only German prisoners. When the war brought an influx of foreign political prisoners, the SS granted the German inmates privileged status, even though many of them were criminals. They were given administrative positions and worked as kapos or Blockälteste—block elders who oversaw the barracks.

They got to keep their hair and wear civilian clothing. Ken had to wear the customary striped uniform and cap, and wooden clogs. He had just turned 20.

———

KR: At the time, I was so small and thin and scraggy that they put me on the children block. I don’t think they even asked me my age. So I ended up on barrack number seven. And the, the Blockälteste was a German called Willie. And he was the most vicious, sadistic person one could ever meet. If there was a prize, he would win it. And the prisoners just were absolutely petrified, including myself.

So he, um, was ruling it with a rod of iron. Any minutest misdemeanor, you, you were given the horse. And that was a wooden frame where the inmate was strapped onto, usually with bare buttocks, and he was administering the lashes. And the inmate had to count it. If you lost count, he started from number one. And he used all his strength. He was literally foaming from the mouth when he was doing it.

Invariably, the punishment used to be 25, but he forgot himself. If he was in the mood, he carried on. Sometimes the prisoner got up half alive, sometimes even dead. It didn’t matter. All he had to do next morning on the Appellplatz [roll call square], he had to produce so many bodies—as long as the count was right, fine.

One day, Willie says to me, “You’re not going to work. You’re going to be my batman.” And that was the rule. Every Blockälteste had a batman. And the batman’s job was to do all his bidding, whatever he wanted. Clean his pitch. Every Blockälteste had a corner of the barrack, a big corner where he had his own bed, white linen, wardrobe, table, chair. A, a small guest house—perfect. You, you ought to look after it, to keep it tidy. Also, you had to wash his shirts, underwear, socks, the lot. So that was my job.

And he was very, very often drunk. There were factories where we were dismantling, uh, shot down Messerschmitts for parts. And what they were doing, they were taking out the antifreeze for the alcohol, I mean from the aircraft meters. And they were sharing it, um, among the kapos.

The Czech inmates used to get parcels from Czechoslovakia. The rule was each one who got a parcel gave half to the kapo. I mean, I mean so they had lots of lovely goodies, um, so they could celebrate between them. And they had little parties.

And he said to me, can I sing? So I said, “Yes, I used to be in the school choir.” He said, “Good.” He says, “Do you know ‘Mamatschi’?” I says, “I do,” because we used to sing it at home, so, uh, because it’s a German classic lullaby. So he, he, he says, “Stay back.” So I stayed back, and those cronies, you know, were sitting around.

So then he says to me, “Sing ‘Mamatschi.’” And I had a little concertina there. And, uh, so I sang, I was doing the entertainment: “Mamatschi, schenk’ mir ein Pferdchen / Ein Pferdchen wär’ mein Paradies.” So, so, uh, fine, everybody was happy. And then they were getting more morose and more drunk, you see.

So when, so when they all went to their respective quarters, uh, he says to me, “Stay.” So I stayed. He says to me, “Strip and go into my bed.” Saying no, he’ll kill me there and then. Look, I mean, you had no choice. So I did. So he, so I was, I wasn’t, I was there quite a while. And I was so frightened, I was shivering so much that the bed was shaking. I didn’t know what he was going to do to me, you see?

So anyway, eventually he comes into bed and I’m just lying. He says, “Turn over.” So, I mean, so I did. So then he there and then—I mean, he raped me. Well, it’s impossible to describe the excruciating pain. It was something—I’ve been hit, I’ve been beaten, but there was no equivalent. I was screaming.

The more I was screaming, the wilder he got. And he was going mad. I expected to be beaten any minute, but somehow he didn’t, you see. Anyway, alright, eventually he spent himself, it was over. So I went back to my bed, you know, in the dormitory.

So then he, he kept me back. On the plus side, apart from not being beaten, he used to give me the odd extra bit of bread. And then he gave me underwear, uh, a vest, and socks, and… Because it was an unwritten rule among the Blockälteste that their possessions, their, their little batmen, were vying with each other, who is better looked after. I was his property, you see?

So, I mean, that was the plus, but the plus reflected itself to Joe. I used to give half to Joe. He didn’t know anything about it; he only knew I was a batman. They kept it quiet, the kapos. Al—although they had a brothel in Flossenbürg, where they used to go. Beh, it was no good because, first of all, it was more or less under supervision, then a short hop and go; well, there they had a, a, a nice youth all night, you see, they could do what they wanted.

SM: After you were raped and when you realized that you would have to go on being abused in this fashion, how did you cope with that, particularly when you were on your own and had time to think?

KR: Well, the only thing I could do is cry on my own. And the reason why I cried—because of the helplessness of the situation, that I was in no position to either refuse or defend myself, you see? In fact, any reaction, um, was, would have been catastrophic. So one had to wear a false smile and look happy because they wanted happy boys round them and not miseries.

Then one day out of the blue, Willie says to me, “You’re going to barrack 15.” He says go to barrack 15, you go to barrack 15—look, you can’t argue. And there the Blockälteste was Max. What I didn’t realize at the time, that they were trading boys between them, you see, and for tobacco and some other things, you see.

So I end up with Max. He was a real pedophile, because I was the smallest there, and he liked to see me strip and watching me for a long time before he did anything. “Stay, turn around, stay,” all this, you know? I mean, he had games, you see, and then touching me and, and that.

But Max, although he was a sadist, much older than Willie, nasty, he, he punished people when they earned punishment, you know, for something. And he wasn’t so wild with the whip, beating it for any excuse. And he was stoutish, sort of fatherly figure, sort of more avuncular, uh, and he treated me well. And he got me extra underwear, fresh towel, and shoes, and, you know? He, he really took the trouble. And he gave me extra bits.

And one of the benefits was I saved Joe’s life. There was another kapo called Heinrich and for some reason or other, Joe fell foul of Heinrich. So Heinrich decided Joe has to go to the stone quarry. There the average time lifespan was two days. If the work didn’t kill you because you were undernourished, you had to lug those big granite stones, and the kapos used to beat you and kick you. They used to dynamite the, the big walls for the stone, no warning. Somebody, somebody got killed—so what?

So they sent him to the stone quarry. So he comes back in the evening, so he says to me, “Romek, if I have to go there tomorrow, I’m dead.” I didn’t know what to do. I was scared of Max, because I told myself, if I ask him or do something, he’ll probably kick me in the bottom and beat me, you see? Because, you know, when he was in a foul mood, that was it. So, um, I couldn’t pluck up the courage.

So then he went for the next day. So then he came back, oh, half ema—emaciated, and he, he said, “Romek, if I go there tomorrow, I’m dead. You’ve got to do something.” As good luck will have it, and, and bad luck, they had a party, you know, the kapos. My usual performance: sing “Mamatschi” and, and all that, and other German sort of songs.

So then when they all dispersed, I, I fell to his knees, and I said, “Do what you like with me,” I said, “but this is Joe, the, my friend from, from my hometown. We went to school together. We were buddies all the years.” I says, “I’ll never forgive myself if I didn’t ask you, I mean, to save him.”

He never said a word. The following day round about 11 o’clock, Joe is back. So obviously, you know, between them, you see… So, um, I saved Joe’s life.

SM: The older men in the barracks, presumably they must have had some idea of your role.

KR: Oh, yes. Oh, oh, jealous. Look, everybody is starving. They’ve got nothing to eat, and people are dying of starvation. I mean, people were dying overnight in bed. The person lying next, next to him used to break their hands if they clutched a piece of bread in it. And by the same token kicking him, them out of bed, um, to make a little bit more room so they could rest a little bit better. People have no idea, you know, what hell it was.

SM: Did they take it out on you because of your favored position?

KR: No, they couldn’t. One word or one touch, it was more than their life was worth.

———

EM Narration: In mid-April 1945, as U.S. troops were approaching Flossenbürg, the SS ordered the camp’s evacuation. Jewish prisoners were scheduled to leave first, but Max, Ken’s block elder, altered Ken’s camp records to say he was Catholic. That only bought him a few days: Ken was sent on a death march to Dachau that killed thousands. He was liberated en route by the Americans.

Ken landed in a displaced persons camp, where he met an Italian partisan who invited him to come to Italy. Ken had heard rumors that Jews were still unsafe in Poland, so he went. While in Italy, he learned that out of 41 family members, only one uncle had survived the war. Ken enrolled in the cadet school of a Polish army unit that was stationed in southern Italy. When the army camp was closed in 1946, Ken ended up in England. He settled in London and took evening classes in engineering.

Over the next two decades, Ken worked his way up through a series of jobs, from delicatessen delivery boy to maintenance manager for a chain of laundromats. Girlfriends came and went. By the mid-1960s, Ken was a self-described “lousy bachelor.” He had just started his own engineering business when a neighbor introduced him to Jimmy Draper.

———

KR: She says that she knows an Irish boy, a nurse. That he’s looking for lodgings. I had, uh, a flat in Camden Road up on top, a small two-room flat. So, um, I said, “Well, I’m not so sure.” But anyway, she said, “Speak to him.” Okay. So I said to him that I’ll prepare an evening meal. And so I did. I did some lovely roast beef and, um, with, with roast potatoes and a soup or something. And, and I had a glass of wine and, and then cherry brandy, things like that.

Anyway, so we sat and chat. He said what he was doing and I—I didn’t tell him my whole story then or anything. Uh, I just said, “At the moment, I’ve only just started my business, I wouldn’t mind sharing with somebody to help,” because I had to pay rates, electricity, “and it’s rather expensive.”

He said fine, we agreed. And we started getting on. He wasn’t easy because he had a sheltered life, you know, in Ireland and all that, so, um, but we got on very well.

And then as my business started getting better and better, our standard of living—I started going to Stamford Hill buying salmon and, uh, the better bits, the better cuts, the better wines. We used to invite friends for dinner. You know, it’s, it, it became much more social. All the, the me—the members of all his family—sisters, the mother came to us, the lot. As far as they was concerned, I was one of them.

And Jimmy kept on getting a better job. So we both had money. We started going on holiday to lots of places. His parents came, stayed with us. We used to go to Ireland. Life was good.

SM: Have you ever returned to your hometown?

KR: No, and I have no intention. It’s a graveyard.

SM: Have you been back to Poland at all?

KR: No. I keep on thinking of going to just have a quick look at the town and probably visit Auschwitz or things like that. But, uh, I was hoping to go to Flossenbürg, but they told me there’s nothing there. It’s all been built up, lovely luxury villas, and they just got a little corner, a garden of remembrance, you know, which is a joke.

SM: How, how do you think you’ve been affected in your life by your experiences during the war?

KR: In a way, I would say broken. I mean, first of all, I have no family of my own. I never got married. That may have something to do with the past. By the same token, it’s, it’s still something that, uh, hounds you—bring up a family, are they going to be victims like you were? And this makes it very, very difficult to, to reconcile.

And then, you talk about normality—all this superficial, you know, bonhomie, wellbeing, the luxuries one affords oneself and all that—but inwardly it is there, and it’s very evident in the dreams, which are absolutely awful to this very day. It’s never left me. At first, I mean, there was usually shooting and, and hounding and… But, but now they become sort of more clouded, more impossible to, to explain.

Just a very, very quick example. I mean, you, you go to see a place and you know where it is. And a few moments later, the, the place is there, but the door isn’t there. You don’t know which way to get out. And, and then you, you go along the road and all of a sudden there’s an enormous steep hill up and you can’t possibly climb it. You can’t, and you sweat—I can feel, I could feel sweating. So then you double back and there’s no road. It was there, but it isn’t anymore.

It’s all these unattainable things. And, and very often I’m being threatened, uh, which I, when I scream—I mean, fortunately, our two bedrooms are not too far apart, so Jimmy has to come in usually to calm me down. So, um, that I would say is the legacy of all the suffering.

SM: Ken, will you introduce us to who’s sitting next to you, please?

———

EM Narration: In the final segment of the videotaped interview, Ken and Jimmy sit side by side in two armchairs in their tastefully appointed London home. Ken, who is small and bald, wears a short-sleeved pale blue shirt and tie. Jimmy has neatly combed white hair. He wears a burgundy V-neck sweater over a dark blue shirt. Ken smiles broadly as he introduces Jimmy, whose eyes widen every so often as Ken sings his praises.

———

KR: Sitting next to me is my very dear and loyal friend, Jimmy Draper. We have been together for 32 years, and, quite frankly, I don’t know what I would do without him. Because he looks after me. He, he makes me feel comfortable. He cares for me. And he also carries quite a lot of my burdens as well. He’s a wonderful, wonderful person.

SM: Jimmy, what would you like to say?

Jimmy Draper: Well, that’s, is a hard one to follow, but what I would like to say is that it’s quite true, I’ve known Ken for all those years. And when I first knew him, I knew little of the Holocaust or of the survivors. And indeed when Ken started telling me about it, I was rather horrified and felt really sad sometimes.

I suppose purely because I was in nursing and it was a caring, caring profession, and I was coming home having administered tender and loving care, hopefully. And I felt sad that Ken should be remembering this kind of event in his life. And I did say to him, “I think it would be a good idea if you now try to forget about it and look to the future.”

He said, very pertinently, “Oh no, Jimmy, I must never forget.” So I didn’t say anything more. Then eventually we went to the ’45 Aid Society annual reunion dinner, and that was my first encounter with a group of people of the same kit and kin as Ken.

And it certainly came home to me that, indeed, it is a fact, you must never forget. I’m not alone now in saying this to Ken because my family—indeed, my father and mother, too—were very proud of Ken, and I always try to support Ken in the work that he does towards the cause of never forgetting. And I hope that for many years, he, he will continue to do so. And for that I wish him a long life.

———

EM Narration: At the end of USC Shoah Foundation interviews, it’s common for the families of Jewish Holocaust survivors to join them on camera—moving, living proof that the Nazis’ efforts to annihilate the Jews failed.

Among the more than 50,000 testimonies of Jewish Holocaust survivors housed in the Shoah Foundation archive, Ken and Jimmy’s joint appearance may be the only instance of a same-sex couple acknowledging their love for each other.

Kenneth Roman died on August 9, 2016. He was 92 years old. We weren’t able to find out what happened to Jimmy Draper. If anyone has any information about him, please write to us at [email protected].

———

Coming up next: Holocaust survivors share memories of Fredy Hirsch, a German Jewish athlete, sports instructor, and guardian of children imprisoned in Auschwitz.

———

This episode was produced by Inge De Taeye, Nahanni Rous, and me, Eric Marcus. Our audio mixer was Anne Pope. Our studio engineer was Katherine Cook at CDM Sound Studios. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Thank you to our photo editor Michael Green, our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham, and our founding production partner, Jenna Weiss-Berman at Pineapple Street Studios.

The interview featured in this episode is from the archive of the USC Shoah Foundation—The Institute for Visual History and Education.

To learn more about the people and stories featured in our episodes, please visit makinggayhistory.org, where you’ll find links to additional information and archival photos, as well as full transcripts.

This special series on the experiences of LGBTQ people during the rise of the Nazi regime, World War II, and the Holocaust is a production of Making Gay History, in partnership with the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale University.

I’m Eric Marcus. Until next time.

###