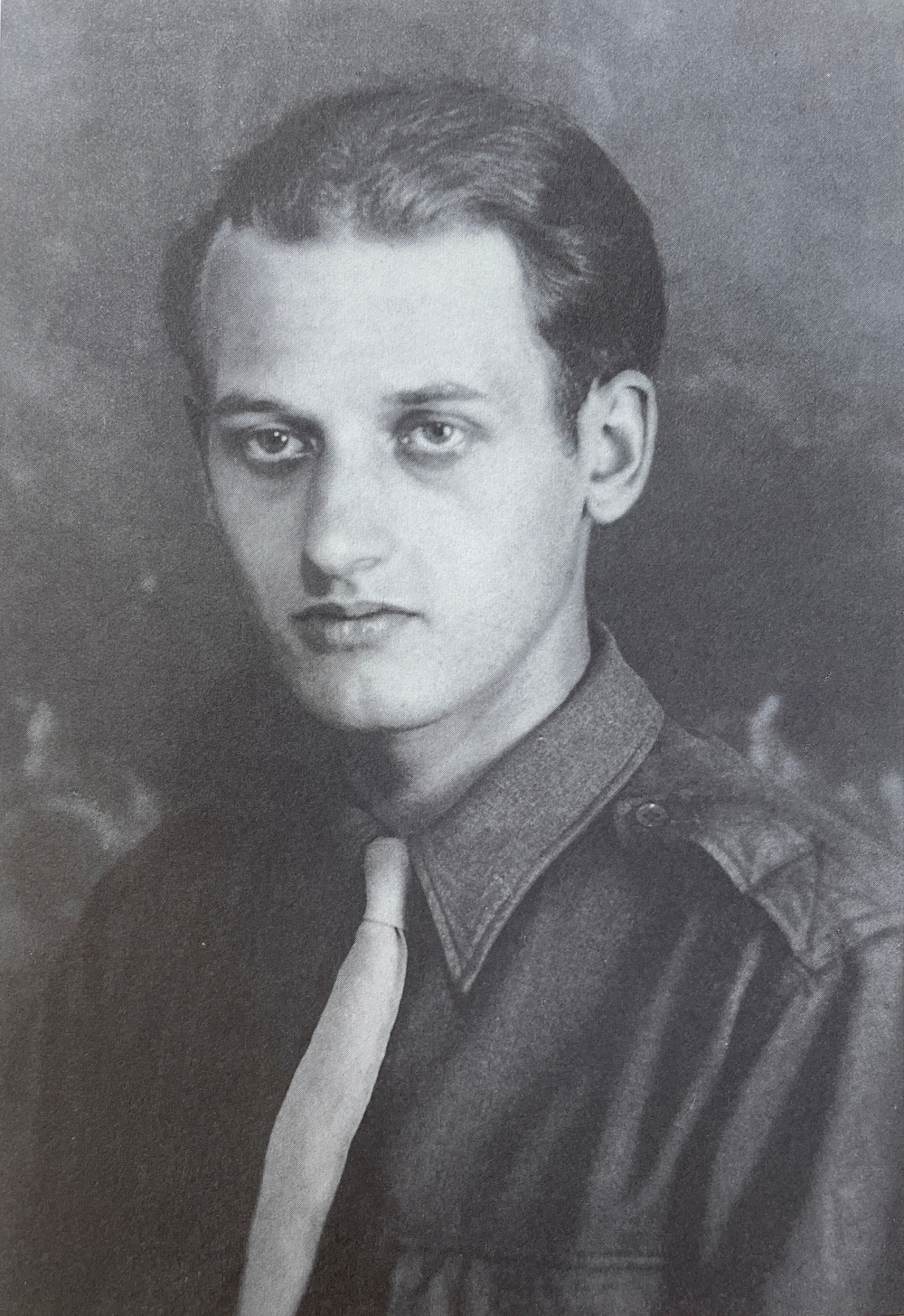

Gad Beck

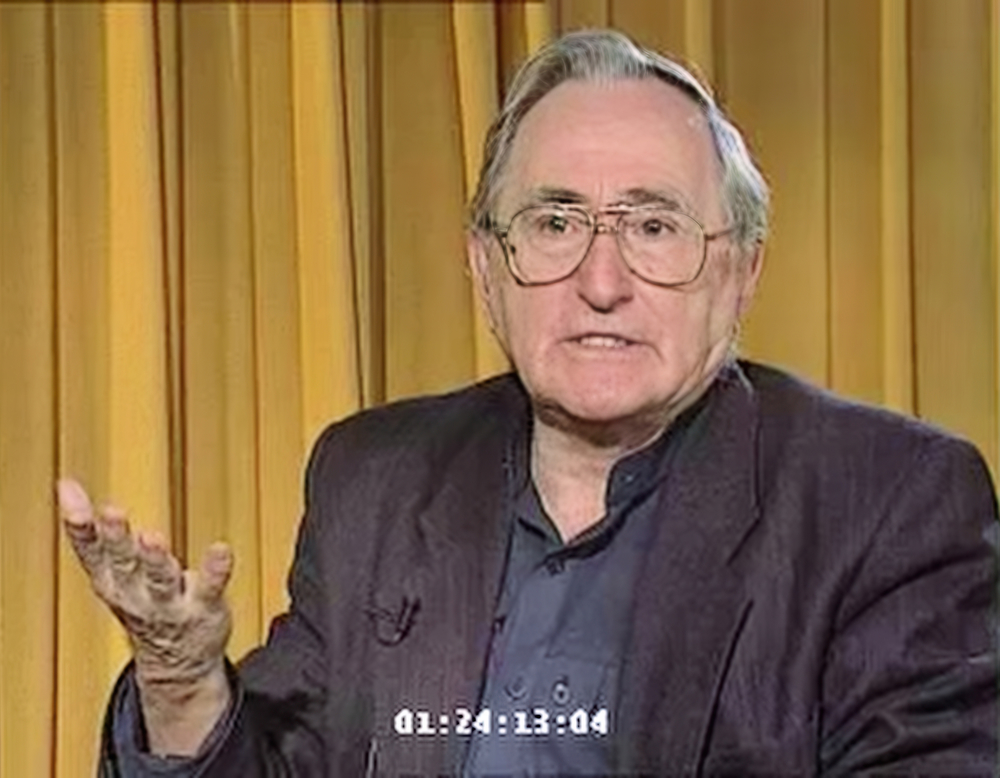

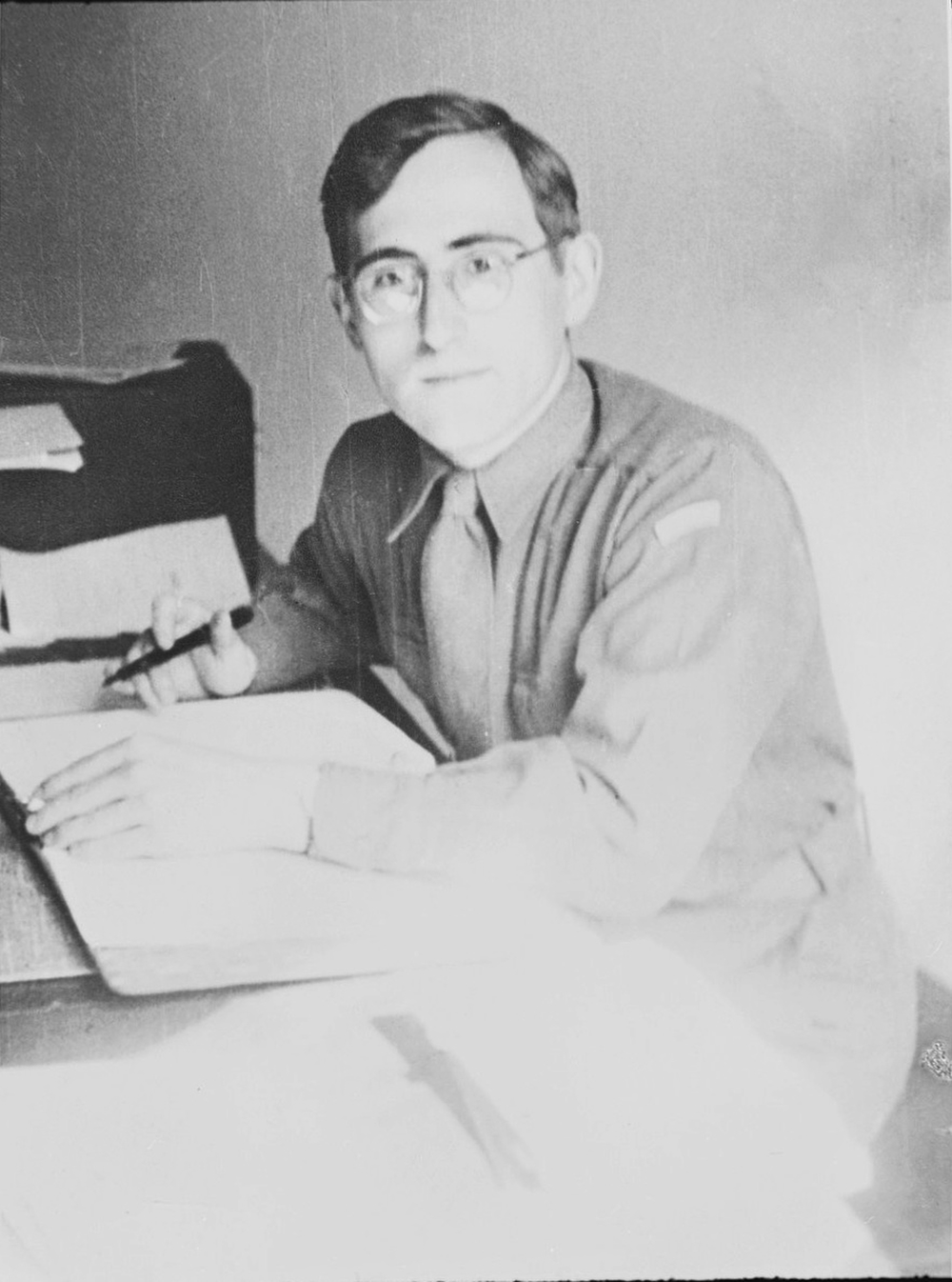

Gad Beck, Berlin, Germany, ca. 1940. Credit: German Resistance Memorial Center.

Gad Beck, Berlin, Germany, ca. 1940. Credit: German Resistance Memorial Center.Episode Notes

After the 1942 deportation of his boyfriend, 19-year-old Jewish Berliner Gad Beck vowed to help others escape the same fate. He became a prominent resistance member and used his resourcefulness, sexual barter, and chutzpah to save fellow Jews from the Nazi murder machine.

Episode first published March 6, 2025.

———

Archival Audio Source

RG-50.030.0361, oral history interview with Gad Beck, courtesy of the Jeff and Toby Herr Oral History Archive, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C. For more information about the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, go here.

———

Resources

For general background information about events, people, places, and more related to the Nazi regime, WWII, and the Holocaust, consult the online Holocaust Encyclopedia of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM).

- Gad Beck’s wartime autobiography, An Underground Life: Memoirs of a Gay Jew in Nazi Berlin (University of Wisconsin Press, 2004), is available here.

- For a concise overview of Beck’s life, read this 2012 Gay City News obituary.

- Beck is featured in Paragraph 175, a 2000 documentary by Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman.

- Beck’s entire German USHMM testimony can be viewed here. There are no subtitles, but the webpage has an English translation of the German transcript. You can watch an additional four-hour interview with Beck on the USC Shoah Foundation website here (registration for their Visual History Archive is free). The latter has German captions; a few clips are available with English subtitles here.

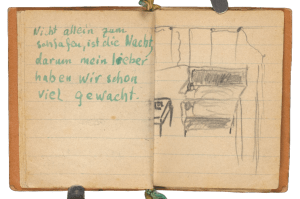

- Beck’s papers reside at the USHMM and include a booklet that Manfred Lewin created for him with memories, drawings, and poems. Go here to explore its pages; for annotations, go here.

- Beck and Lewin’s love story was the inspiration for one of the acts in Two Remain, a 2016 two-act opera by composer Jake Heggie with a libretto by Gene Scheer. To learn more and listen to the work, go here.

- To learn more about Zvi Aviram, have a look at this interview from Yad Vashem’s Survivors Testimony Films Series.

- Stella Goldschlag, who’s briefly mentioned in the episode, was a Jewish Gestapo informer responsible for the arrest of possibly more than 2,000 fellow Jews. Learn more about her in Peter Wyden’s Stella: One Woman’s True Tale of Evil, Betrayal, and Survival in Hitler’s Germany (Anchor, 1993), of which you can find a summary here.

———

Episode Transcript

Gad Beck VO: When my twin sister was born, she slipped right out of mother, happy and fat and round. Nothing else came out. The midwife said, “Listen, Mr. Beck, something’s wrong. The afterbirth didn’t come out. Your wife has a fever. You have to get the doctor.” The doctor bent over and looked inside… “Oh my God,” he said, “there’s something else in there.” This “something else” was me! He pulled me out onto the table and I was blue. The doctor said calmly, “Mr. Beck, you have a daughter. Your wife is recovering. You’ll be okay, right?” He’d written me off! I was this little blue worm lying on the table. But the midwife held me up like a rabbit and smacked me on the behind. I cried—I was alive! So my first pleasant physical sensation was a smack on the behind.

———

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History: The Nazi Era.

Gad, or Gerhard, Beck and his sister Miriam were born in Berlin on June 30, 1923. Their Jewish father was from a religious Viennese family. Their mother was a Christian Berliner. Gad grew up celebrating Jewish holidays at home and going to church with his Christian grandmother. His father ran a small mail-order business—first toys, then tobacco and cigarettes. Gad and his sister helped with deliveries.

Gad was interviewed in Berlin in 1996 by Dr. Klaus Müller for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. His breezy account of helping Jews escape the Nazi murder machine downplays the peril he faced as a gay Jew in wartime Germany. Gad begins his story in 1933. He was 10 years old.

———

GB VO: Then Hitler came. My parents didn’t take him seriously at all. We lived on a street with a lot of communists and social democrats. Within months, the SA, Hitler’s Stormtroopers, were parading on our street. They’d drag communists out of their houses and beat them. The Kohn family from next door were staunch communists. They were beaten. My father said, “It’s not because they’re Jews, it’s because they’re communists!” My parents didn’t want to admit that Jews were being targeted. No, those people were communists, and my father didn’t like communists very much either.

But even after just three weeks you could already feel a shift. My class turned brown. The Hitler Youth had to wear these brown shirts and pants—and slowly the class changed color. The comments started: “Can I sit in the back? It stinks of sweaty Jewish feet up here.” Soon everybody was sitting in the back and I was isolated. I told my parents, but they said, “Ah son, don’t be so dumb! The Germans won’t be misled by a mere house painter. It will all be over soon.”

Soon my school was renamed after a fallen Hitler Youth. Everybody had to assemble in the schoolyard. I started to head out, too, but my teacher said, “No, no, not you. You stay here.” He brought me out separately to the schoolyard with 12 other boys—all the Jews in the school. They stood us against a wall across from the rest of the students. The flags were raised—the German flag, the Nazi flag, the Hitler Youth flag. And then they sang their songs and raised their arms in the Nazi salute, almost as if to slap my face. From that day on it was the same every morning. They called it the pledge to the flag ceremony.

I went home. I cried. And I said to my mother, “Mutti, I can’t do it! What have I done to them? Why do I have to stand there?” And again she said, “It will pass. Nobody is doing anything to you.”

In 1934 I was picked to run in a relay race at the youth sports festival in Weißensee. I ran last and I won! My heart was thumping, I was so excited! But my teacher said, “No, of course you can’t go on the podium, man. You are not allowed to raise your hand in the German salute!” He put another boy on the podium in my place. My mother was there and saw what happened. The next morning, she went to the school director and said, “I will not let my child be destroyed,” and she pulled me out of there.

I then had to go to a Jewish school because once a Jew left a German school, he couldn’t go to any other German schools. This new school was hugely overcrowded. Many, many Jews had to leave their other schools, and the community bought and rented factories to provide enough places for Jewish children. The school was a world unto itself, with its own sports field, with a theater for the Jewish youth—I lived in a Jewish world.

It was a renowned and popular school, and it was Zionist. For the first time in my life, I was exposed to Zionism, Jewish nationalism, the goal of the Holy Land as fatherland. There was a lot of emigration already in 1934, ’35, and many of my classmates from this school survived only because they went to Palestine, where you could immigrate with a little less money than anywhere else.

During this time came the high point of my life. I was very good at sports. My gym teacher wanted me to be a hurdler. He said, “You don’t jump, you fly over the hurdles.” He was preparing me for a sports festival. One fine day I blissfully flew over the hurdles. He was very happy about it. It was wonderfully beautiful. And he was wonderfully beautiful.

We talked and stood in the shower and I saw his beautiful body. He put on a bathrobe. I ran after him and crawled under his bathrobe. I forced myself on my teacher! It was the experience of a lifetime.

I dashed home and cried out, “Mutti!” “What happened?” she said, “Did you have a good report card?” “No,” I said, “I had my first man.”

It was 1935. My parents were in a very bad way. They felt the boycott against Jewish businesses. They had problems that they hid from us. I was the happy type and that made the whole family happy. “I had my first man today, Mutti.” She ran to tell all five of her sisters. They came, one aunt after the other, to see how I looked now that I’d been with a man.

I became a sensation in our so-called boring family. After that, I no longer had to hide anything at home. My mother accepted it from the first minute.

Nothing came of it with my gym teacher. But from then on my desire for other bodies was ignited. So during this horrible time, I had the most profound experience of my life. I became open about my sexuality, and no Hitler or anybody else got in the way of it.

———

EM Narration: Meanwhile, the situation for Jews in Germany was growing increasingly dire. They’d been barred from holding public office, working in certain professions, and serving in the army. In 1935, the newly imposed Nuremberg Laws stripped them of their citizenship.

On the night of November 9, 1938, Nazi forces attacked Jews and Jewish property across Germany. They killed dozens of people, burned more than a thousand synagogues, desecrated cemeteries, arrested 30 thousand Jewish men, and looted Jewish-owned businesses. That included the tailor shop where Gad worked after his parents ran out of money to pay for school. The coordinated rampage came to be known as Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass.

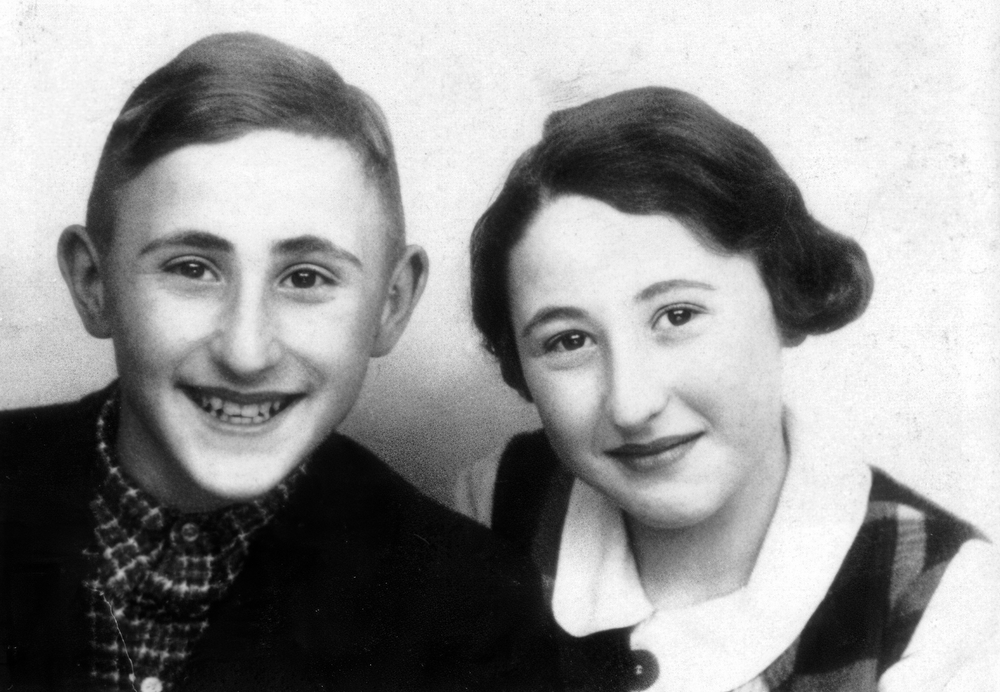

New residency laws required Jews to live in designated Jewish neighborhoods. Gad’s family was forced to leave their home and move in with strangers. Gad went to work at a Zionist agricultural farm where young people were preparing to emigrate to Palestine. But in 1940, he was injured and missed the last ship out. He returned to his family, went to work in a cardboard box factory, and joined a Zionist youth group that was meeting in secret. That’s where he found Manfred Lewin.

———

GB VO: It was a never-ending love. Manfred was from a very poor family. There were five children, an aunt, a grandmother, a sick father, and a sick mother. He and one brother were the only healthy ones. Another brother had a humped back and they were all asthmatic. They had all the illnesses that poor people have. They were good people, loving people.

Their house was so full of bugs you shouldn’t have been allowed to go in. We had sex in spite of the bed bugs. We tried putting some of the bugs in a bucket of water, but they didn’t drown. They were used to it. They just crawled out and came straight for us.

Our love was so strong. The nights were ours because we simply couldn’t hold out anymore. It was different for me this time. I was not the assertive one. He took me. It was a new step in my development.

In the mornings we took the same subway. I went to my job and he went to his. He worked for a house painter who renovated apartments that had been damaged by the bombings. It was a good job—very hard and dirty work, but pretty secure.

I took him home to my mother’s family and they promised us that if we were ever in trouble we could always come to them.

I volunteered for the Jewish community serving soup at the Grunewald train station, so I saw the transports. People were put into freight cars that had signs that read, “For seven horses,” but 75 to 80 people were crammed into them. Some friends of mine ended up in there, and a girl from the youth group. All we could do was say goodbye. 1941-42 was the year of goodbyes.

One evening I went to find Manfred. His brother was home with the little one. “Where is Manfred?” I said. “They came and took them all,” he said, “the whole family. Tomorrow morning we have to go, too.” It was a night I will never forget. I kept thinking, don’t go crazy, you have to think, you have to do something… Afterwards, his brother and I made love as we cried. We simply gave ourselves to each other.

The next morning I went to Manfred’s boss, a wonderful Christian man. I said, “They’ve taken Manfred.” “That’s nonsense!” he said, “We need him!” Then he made a face and said, “Are you brave?” “Yes.” He said, “My son belongs to the Hitler Youth. Put on one of his uniforms and go get Manfred out of the transit camp. Tell them he’s trying to commit sabotage, that he has the keys to all the apartments and the brushes and the paint and that we can’t do any work without him.” He gave me the uniform. His son was not my size, he must have been six foot five. I had to roll things up and tuck things under. If I had been an SA man, I would have arrested me on the spot.

I went to the central deportation center, which was located in my old school. Next to it was the transit camp. I walked in and spoke to the Sturmbannführer: “You have the Jew Manfred Israel Lewin here. He’s a saboteur. He has all the keys and all the paint brushes and paint. We can’t prepare the apartments for people.” “Hmm, Manfred Lewin?” Manfred came out. He saw me in the uniform and didn’t bat an eye. “You’ll bring him back won’t you?” the Sturmbannführer said. “Yes, of course. What am I going to do with a Jew!”

We walked out the door together. I gave Manfred 20 marks and said, “Go immediately to Uncle Bobby’s. I’ll come later.” He took the 20 marks. We walked a little way and then he said, “No. Gad, I can’t come with you. My whole family is back there. They are old and sick and exhausted. I will never feel free if I run away from them now.” He turned around and went back.

At that moment, I thought everything was falling apart. But it didn’t take long for me to decide that I had to plan ahead. That I had to take people underground before they got taken away. And not wait.

———

EM Narration: Manfred’s family was deported in November 1942. The official order stated that they were being taken for “work in the east.” Gad didn’t find out until later that the entire Lewin family was murdered shortly after they arrived at the Auschwitz concentration camp.

In 1943, after two years of mass deportations, the Nazis declared Berlin officially free of Jews. But there were still thousands of Jews living in the city, mostly in hiding, and their situation was perilous.

Through his Zionist youth group, Gad got involved in the underground and soon became a leader of his resistance cell. He used his resourcefulness, connections, and often sexual barter to help Jews obtain fake IDs, food, hiding places, or an escape to Switzerland.

Gad’s own alias was Gunther Kaplan, a stateless Catholic. He had a forged doctor’s note that said he had tuberculosis and should be released from military service.

In 1944, Gad met Paul Dreyer, a non-Jewish engineer who let him use his secretary’s apartment in exchange for sex.

———

GB VO: Dreyer’s apartment became my headquarters. I was helping groups escape—people who’d been rounded up by the Gestapo and were being held until they would be deported east. I’d spring them out of detention and bring them to this apartment.

It wasn’t all that difficult. They were all doing forced labor, clearing debris from the streets. So with one group, we decided that at exactly 12 o’clock, all six people who were working on different corners would say to their bosses, “I have to go pee.” They all ran off at 12 on the dot and were in the apartment at 12:15. The Gestapo might have been aware of us before, but from that moment on, they had to start taking our organization seriously.

This gay engineer Dreyer, he was a good guy and he wanted to help us, but he was a floozie by nature. He came to see me twice a week and it was very unpleasant, but there was nothing to be done. He brought us food and so on. He wasn’t my type, but he wasn’t rough and he wasn’t mean.

But it was because of him that I got caught.

———

EM Narration: Dreyer was approached by a man claiming to be in the Jewish underground who offered him diamonds and jewelry to sell on the black market. It turned out to be a trap. The man was working for Stella Goldschlag, a Jewish agent of the Gestapo who denounced hundreds of fellow Jews to the Nazis in exchange for money and protection. Dreyer, Gad, and his new boyfriend, Zvi, were all arrested.

———

GB VO: We were brought to Gestapo headquarters in February of ’45. By that time, I was a prominent member of the underground. I couldn’t begin to imagine who’d run the whole operation in my absence. I’d given the money to someone to look after, so there was no lack of funds. Whoever could still get food would buy and distribute it. Besides, it was abundantly clear that the war could only last a few more months, not longer, it was coming to an end.

Still, some things happened that probably wouldn’t have happened if I’d been around, like when the Gestapo found two of my boys. Someone heard them flush the toilet during an air-raid alarm in an apartment that should have been empty. The boys shot their way out to boot—one of them killed two German soldiers. I’d given guns to 50 or 60 people, because now that the war was coming to an end, we thought, we’ve held out this long, now we get caught only over our dead bodies.

The prison where we were held had been established in the basement of the Jewish hospital. Among the guards was a nice Saxon policeman, a simple civil servant, not SS. I wrote a poem—I’ve written a lot of poems in my life—and this policeman passed it to little Zvi for me. He came back and gave me a lock of Zvi’s hair wrapped in a thin white piece of fabric. It was a sign of love. At that moment I knew he was strong, and he knew I was strong.

Moments like that are so rarely touched upon when people write about heroism. All of this is really the opposite of heroism. It’s that undying part of being human that keeps us strong for the tasks that remain. Because even in prison, you still have responsibilities.

I was brought to the notorious Möller one day to be interrogated. He was one of the most dangerous people in the Gestapo. A primitive kind of man. So this man receives me in his office. And there’s my briefcase on the table—it had my receipt book of underground transactions and also some of my poems. On the other side of the table was a thumbscrew. It was absolutely clear that this man was not going to let me leave unscathed.

Now it just so happened that I knew this man from before the war, but he didn’t recognize me. He looked in my briefcase and pulled out a book of poems—love poems—that I had written to a woman friend in Auschwitz. “So you had time to write some gay-boy love poems, huh?” He couldn’t fathom that I’d write to a woman. He thought it was to some man.

I was afraid he would look inside the briefcase again and see the book of receipts. So I said, “We’ve seen each other before, Mr. Obersturmbannführer.” There was no expression on his face. I had to keep talking. I said, “Your wife, she had a kiosk down there in Hohenschönhausen. My sister and I delivered cigarettes there. My father had cigarettes, cigars, and we brought them down, we always drove down there in the car, and your wife always gave us lollipops. Two pennies each!”

“No, two for a penny,” he said. And I saw the corners of his mouth turn upwards. “Enough already,” he said, “out!” He didn’t do anything to me.

———

EM Narration: Zvi wasn’t so lucky. Gad could hear his screams from the next room as he was brutally interrogated about the nature of their relationship. Finally, Zvi was also let go.

———

GB VO: We were taken back to the bunker on the subway wearing our shackles. Zvi was a little bloody, but not too bad. We stood next to one of the poles, holding each other, and he said, “You didn’t cry.” He was happy. He’d been really afraid that they would beat me, too.

One day we were sitting in the bunker and there was another air-raid alarm. Suddenly a bomb hit the bunker and covered me in debris. I was buried and I could hear people screaming. The Gestapo chief came and said, “Whoever gets him out alive will be released immediately.” They dug, and they dug, and they dug; it was 11 hours until my head was free. A little Frenchman pulled me out of there. I still had a few crushed cigarettes in my pocket. I gave him one, and he took it and smiled and said, “Encore une.” So I gave him another.

I was taken to the hospital upstairs. The doctors there were determined not to operate or do anything but relieve the pain. It was a race against time. Would the Russians make it soon enough? And this is really unbelievable, but in April of ’45, in the middle of the battle for Berlin, they posted two SS people at the door to my hospital room. They had them standing there instead of fighting for Berlin—unbelievable! As if I could escape! I couldn’t even move.

One day they brought me back down into the bunker. Someone was there in the corner—little Zvi! “Gad,” he said, “the people have all been liberated, but they won’t let me go.” It seemed obvious what they were going to do with us. I couldn’t console him.

And then one night, we heard the sound of marching feet outside, and the Sturmbannführer came in with pieces of paper in his hand, and he ripped them up. They were the pieces of paper we’d signed when we were arrested that said we were condemned to death because we were against the German people. Then he went out, and left the door open.

Little Zvi ran out after him but came right back. “For God’s sake, Gad,” he said, “they’re shooting all over the place right here above us. This here is the epicenter.” And it really was the epicenter of the Russian battle for Berlin. Seestraße is a street that rings the city. Whoever controls it has control of Berlin. “We’re staying down here,” Zvi said. I hadn’t eaten for days, but food was not on my mind.

At some point, the fighting got louder and louder, and during the night things got worse and worse, and then you could hear Russian voices—Russian!

One of them came down the stairs. Like in a Soviet propaganda film, injured here and there, ripped up—and a really handsome man to boot. He stood there and took a piece of paper out of his pocket, and said in Yiddish:

GB: “Iz do eyner vos heyst Gad Beck?”

GB VO: “Is one of you Gad Beck?” He was a Jew from the Red Army! He said:

GB: “Brider, di bist fray!”

GB VO: “Brothers, you are free!” So that’s the story. It doesn’t end in German. It ends in Yiddish.

———

EM Narration: Gad and Zvi were liberated by the Red Army on April 24, 1945. But when the war was over, Gad discovered that the Soviets had no warm feelings for Jews, and a particular hatred for Zionists. He made his way to the American zone in Munich and found work collecting census numbers on Jews in displaced persons camps.

Gad’s parents and sister also survived the war. In 1947 the family moved to Palestine, though Gad’s father died soon after. Zvi immigrated in 1948, the year the state of Israel was established. He lived with Gad and his mother for many years. He later married a woman and started a family. Zvi and Gad remained close friends.

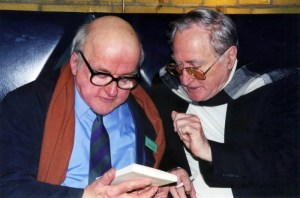

Beginning in the late 1970s Gad traveled often to Germany where he lectured about Jewish life. That’s when he met Julius Laufer, his partner for the rest of his life.

Gad published his autobiography in 1995. Its English translation is called An Underground Life: Memoirs of a Gay Jew in Nazi Berlin. Gad participated in the 1997 New York City gay Pride march, riding joyously down Fifth Avenue on a float sponsored by the world’s largest LGBTQ Jewish congregation.

Gad Beck died in Berlin in 2012. He was 88 years old.

———

Coming up in our next episode, Lucy Salani escapes from three armies and survives Dachau. She’s one of the only transgender people to testify about their experiences in Nazi concentration camps.

———

This episode was produced by Nahanni Rous, Inge De Taeye, and me, Eric Marcus. Our audio mixer was Anne Pope. The English voice over was provided by John Cariani; translation help was provided by Agnes Krup.

Our studio engineers were Michael Bognar and Tucker Dalton at CDM Sound Studios. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Thank you to our photo editor Michael Green, our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham, and our founding production partner, Jenna Weiss-Berman at Pineapple Street Studios.

The interview with Gad Beck was provided courtesy of the Jeff and Toby Herr Oral History Archive at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

To learn more about the people and stories featured in our episodes, please visit makinggayhistory.org, where you’ll find links to additional information and archival photos, as well as full transcripts.

This special series on the experiences of LGBTQ people during the rise of the Nazi regime, World War II, and the Holocaust is a production of Making Gay History, in partnership with the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale University.

I’m Eric Marcus. Until next time.

###