Fredy Hirsch

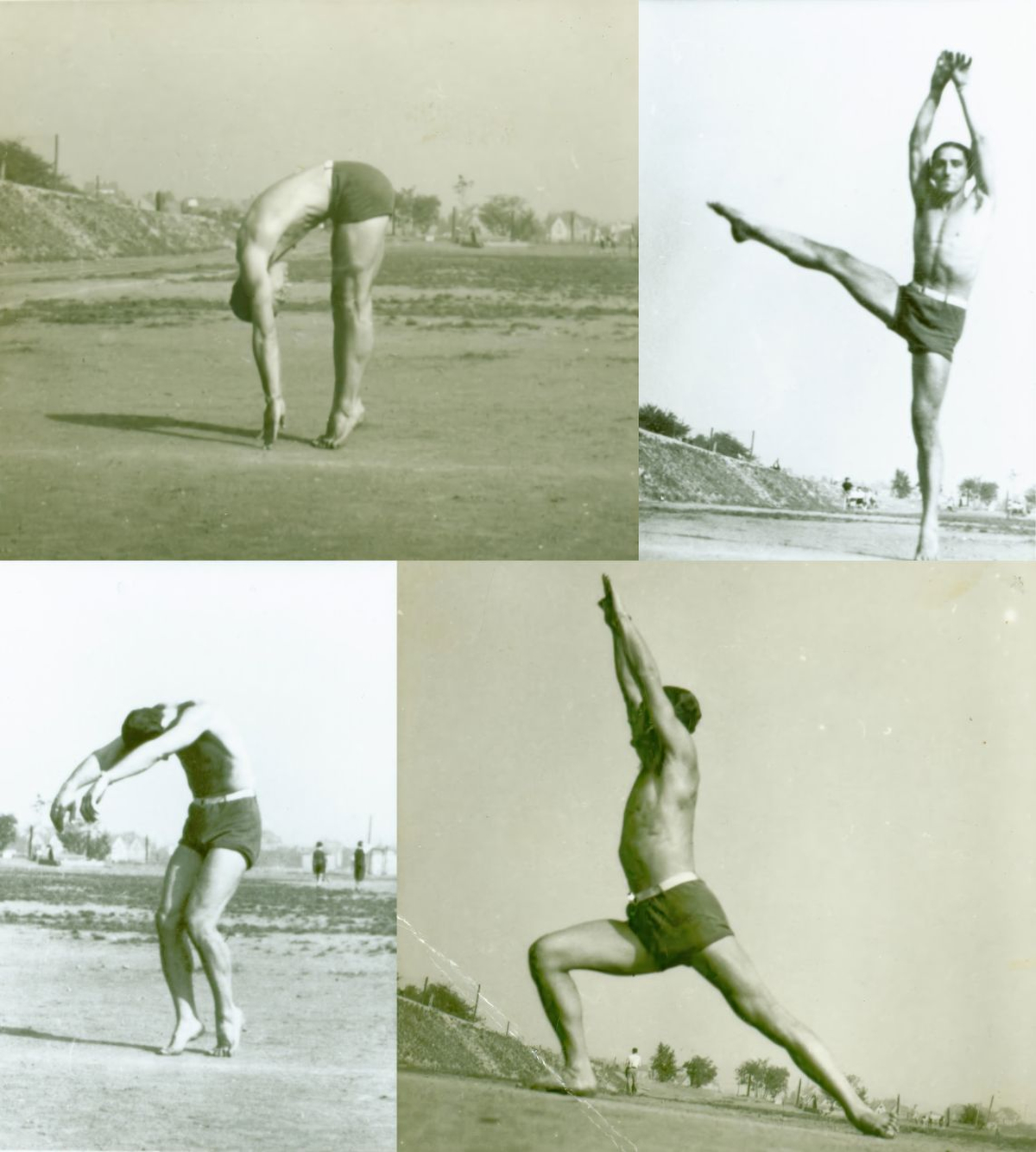

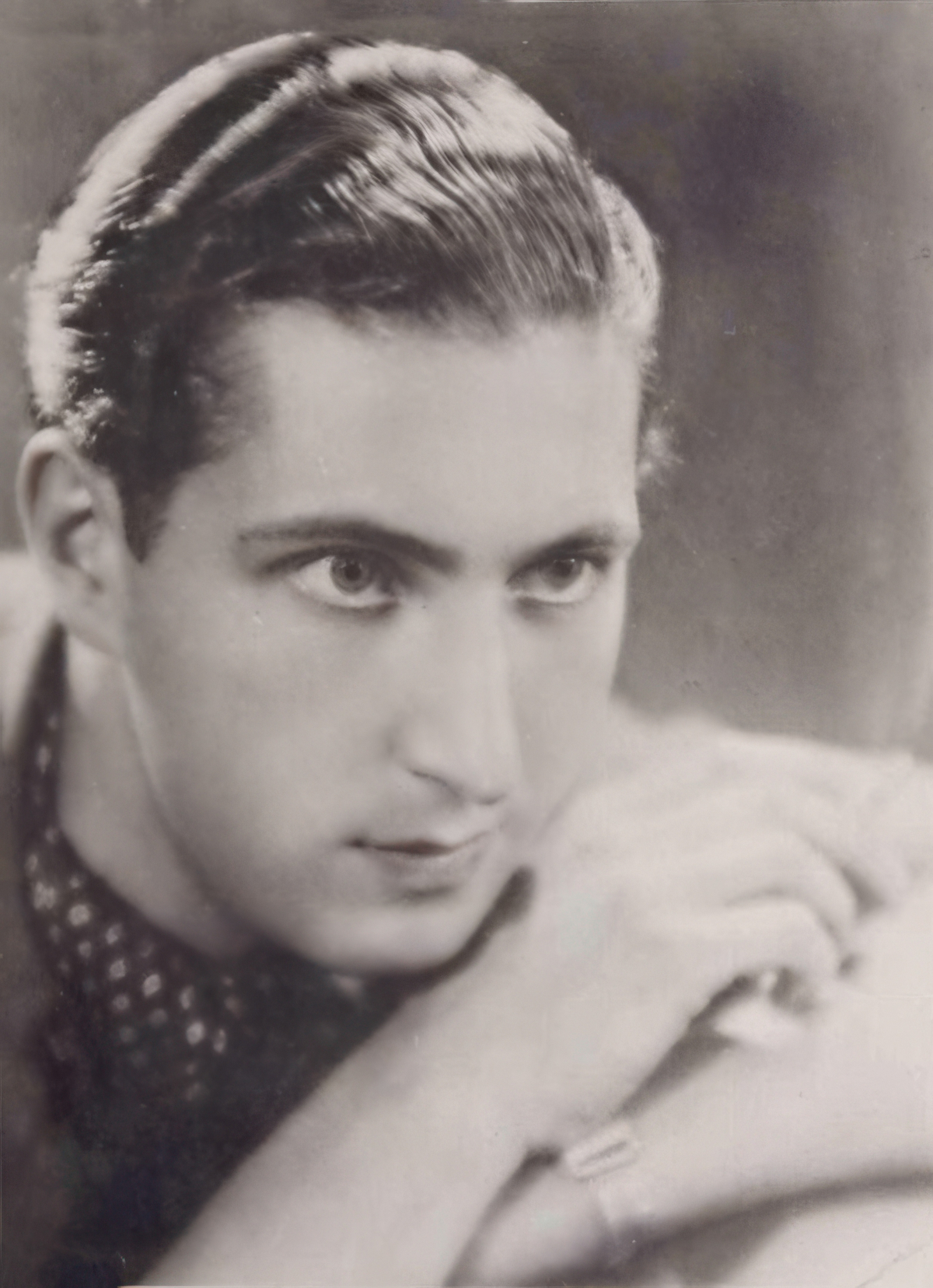

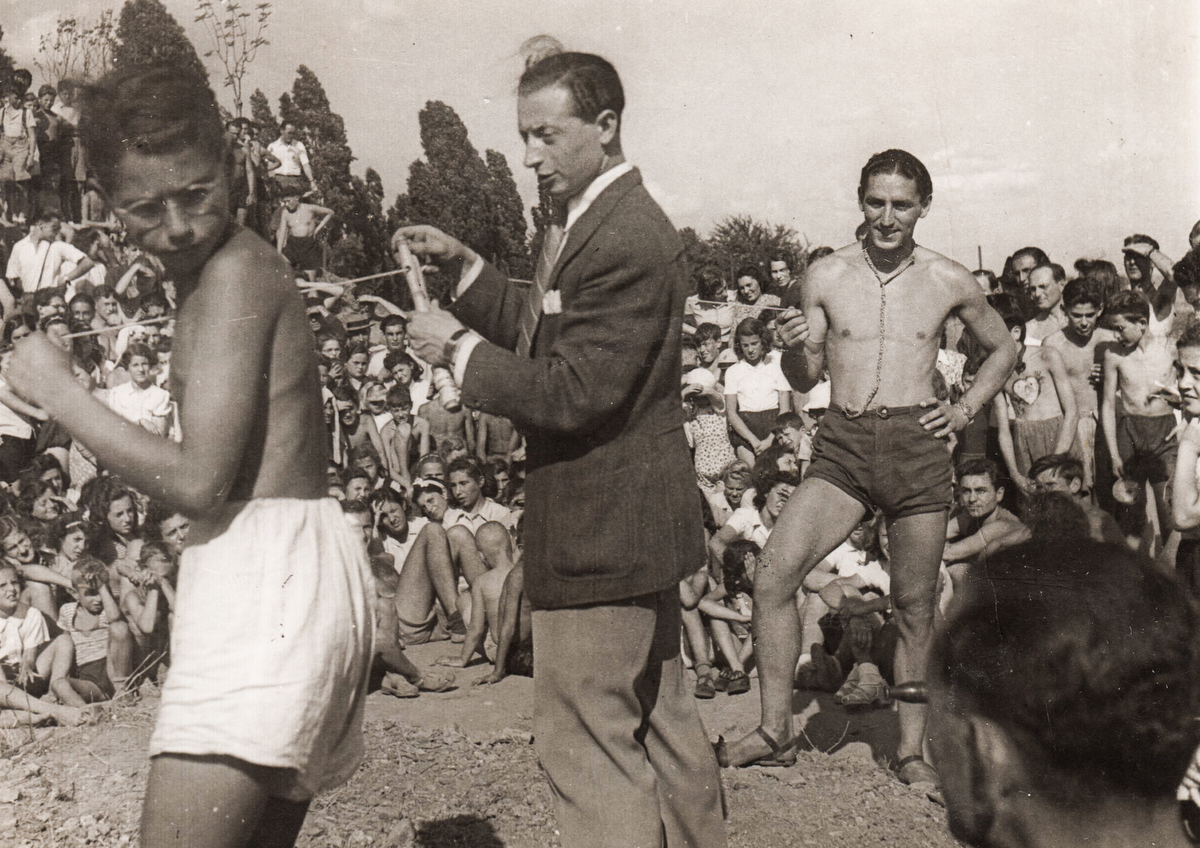

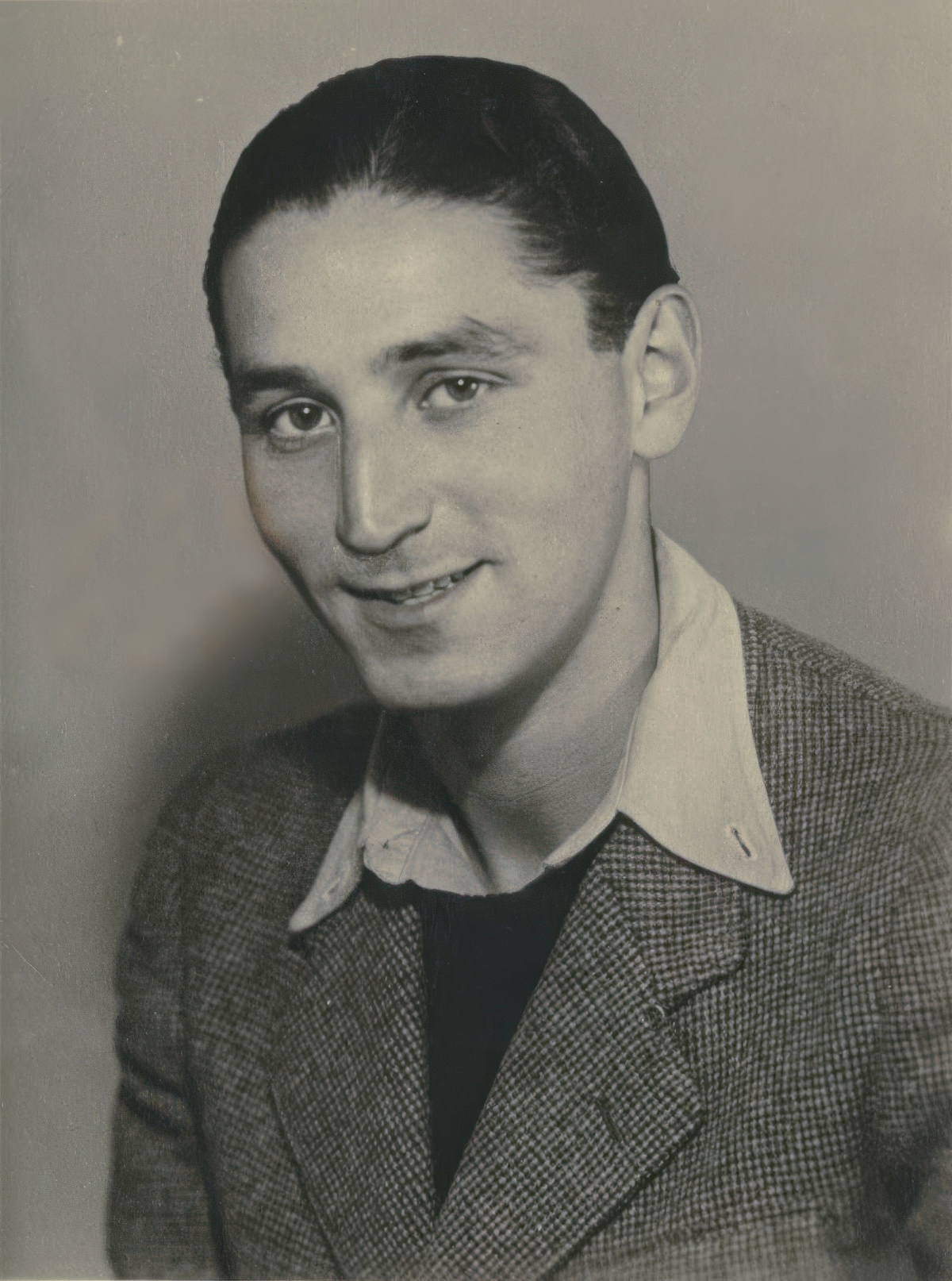

Undated photo of Fredy Hirsch. Credit: Beit Theresienstadt, Kibbutz Givat Haim-Ihud, Israel.

Undated photo of Fredy Hirsch. Credit: Beit Theresienstadt, Kibbutz Givat Haim-Ihud, Israel.Episode Notes

Charismatic German Jewish athlete Fredy Hirsch dedicated himself to inspiring and protecting children imprisoned by the Nazis. In this episode, survivors of Theresienstadt and Auschwitz whose lives were made tolerable, sometimes even joyful, thanks to his selfless efforts share their memories.

Episode first published April 3, 2025.

———

Archival Audio Sources

-The following interview segments are from the archive of the USC Shoah Foundation – The Institute for Visual History and Education:

- Dina Gottliebova-Babbitt, © 1998 USC Shoah Foundation

- Michael Honey, © 1997 USC Shoah Foundation

- Peter Mahrer, © 1998 USC Shoah Foundation

- Helga Ederer, © 1997 USC Shoah Foundation

- Yehudah Bakon, © 1996 USC Shoah Foundation

- Melitta Stein, © 1996 USC Shoah Foundation

- Eva Gross, © 1996 USC Shoah Foundation

- Chava Ben-Amos, © 1997 USC Shoah Foundation

For more information about the USC Shoah Foundation, go here.

-The following interview segments are from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, Washington, D.C., courtesy of the Jeff and Toby Herr Foundation:

- RG-50.030.0488, oral history interview with Ursula Pawel

- RG-50.477.0497, oral history interview with John Steiner, gift of Jewish Family and Children’s Services of San Francisco, the Peninsula, Marin and Sonoma Counties

- RG-50.106.0061, oral history interview with Rene Edgar Tressler

For more information about the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, go here.

-The Rudolf Vrba audio was drawn from footage created by Claude Lanzmann during the filming of Shoah. Used by permission of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Martyrs and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority, Jerusalem.

———

Resources

For general background information about events, people, places, and more related to the Nazi regime, WWII, and the Holocaust, consult the online Holocaust Encyclopedia of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM).

- For an overview of Fredy Hirsch’s life and his efforts to improve the lives of the children in Theresienstadt and Auschwitz, read this Holocaust.cz article.

- Hirsch is the subject of Heaven in Auschwitz, a 2016 documentary directed by Aaron Cohen that’s available to rent on Vimeo (where you can also watch the trailer). It features several of the people whose voices you can hear in our podcast episode.

- A 2017 documentary by Rubi Gat titled Dear Fredy also explores Hirsch’s life. You can watch the trailer here; the film can be streamed for free in the U.S. here.

- For a glimpse into Hirsch’s private life, read Dr. Anna Hájková’s “Fredy Hirsch’s Lover” (Tablet, May 2, 2019).

- For a deep dive into life in Theresienstadt: Hájková is also the author of The Last Ghetto: An Everyday History of Theresienstadt (Oxford University Press, 2020).

- This Holocaust.cz page provides additional context about the Czech family camp in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

———

Episode Transcript

Dina Gottliebova-Babbitt: Fredy Hirsch was a young man who came to Brno at first fleeing Hitler. He was the epitome of tall, dark, and handsome. He looked like a toothpaste advertisement. He had this, uh, shiny black, slick black hair, very handsome face, and an incredible grin with white, white teeth.

Michael Honey: Well, Fredy Hirsh was quite an extraordinary man. A, a tremendous gymnast. Laughter was around him always.

Ursula Pawel: He was, you know, the—some people, you can’t analyze what makes this guy be appreciated and respected by everybody, what makes him a leader. And that was Fredy Hirsch.

DG: He was gay, which, we didn’t know and didn’t care. He was just one of us. And, uh, the reason I mention it now that he was gay is because he was a wonderful, wonderful man, and he did a lot of good things in very difficult situations for children, mainly. And because very often gays are maligned and spoken of badly, I think it’s important that if we know somebody that great—and he was great—who happened to be gay, that we say so, you know. I mean, it, it should be known, I think.

———

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History: the Nazi Era.

Fredy Hirsch was born in 1916 in Aachen, Germany. As a teenager, he was a leader in local Jewish youth movements. Fredy fled Nazi Germany in 1935 and moved to Czechoslovakia. He settled in Prague, where he worked for the Zionist youth movement Maccabi Hatzair, organized sports competitions, and helped Jewish teenagers prepare for immigration to Palestine.

To tell his story, we’re relying on the memories of people who knew him. We begin in 1939, after the Nazis invaded Prague.

———

MH: There were two leaders who shared the national leadership of Maccabi Hatzair, Fredy Hirsch and my brother Shraga. Um, and they had to decide who will go to Palestine and who will lead the movement in, uh, in occupied Czechoslovakia. And, uh, they did it by, you know, drawing the matches; they broke a match and whoever got the broken match stayed. And my brother got the, uh, he chose the right match.

———

EM Narration: Fredy drew the short stick and stayed behind to lead the youth movement. Czech Jews soon became subject to the same treatment as Jews in Germany. In 1939, fascist forces attacked Jews and synagogues; Jewish doctors, lawyers, and business leaders were banned from working in public institutions; Jewish businesses were seized.

———

Rene Tressler: Even the Jewish school after a while got closed. The only thing they, the Germans allowed us to do—the, I’m, I’m talking about the youth, the kids, you know—were, there was a sport club in Prague, a very famous one. The name is Hagibor.

And they allowed that sport stadium to be in the hands of the Jewish community in Prague, and the Jews—the Jewish kids and even adults—were allowed to go there and play, and play sports and exercise and so forth.

Fredy Hirsch, he was also the leader put in charge of that sports stadium during the Hitler-occupied time. And, uh, so we went there and we played soccer and we had a gorgeous soccer team.

He, uh, also advocated for us to exercise and to learn discipline and to be physically fit and mentally fit. And that was his, his way of teaching us, you know, which we hated, cause we wanted to play soccer and he couldn’t stand it. He just exercised, and so, and scouting, you know, and discipline and military and marching. Uh, but, uh, we found out later that it was pretty good for us and that he was doing the right thing.

Peter Mahrer: The Jewish life was rapidly disappearing because the transports from Prague, uh, started. So every week there were a thousand people, uh, who disappeared and really, uh, the life in that part, in these couple of years, uh, just revolved about who’s going in the next transport and, uh, how do we help them.

Uh, I had been working with a group of, uh, uh, young men who were helping, uh, the Jews who were put into the transports that went first to Theresienstadt and eventually, uh, to Auschwitz. They were allowed, uh, one or two suitcases, and many of them were elderly and couldn’t, uh, couldn’t carry that. So we as youngsters went out in the morning with, usually in a horse-drawn carriage, and, uh, helped these people with their luggage and took it to the, to the assembly center. And this was organized by, uh, Fredy Hirsch.

John Steiner: Fredy understood the tremendous trauma of all the people who had the notification to go to the assembly places and be without any sort of support system, because so many people are old, didn’t have any relatives, no one to help. So he, under his leadership and with the help of kids like myself, we had special permission from the Gestapo to pick up the people from the places where they were to be deported, and help them to go to the assembly center, uh, and, and see to it that they would come there in one piece. Now, well, that may not have been viewed in retrospect as a great, uh, favor, you see, but on the other hand, we, uh, tried to avoid that the Gestapo would come and use force.

———

EM Narration: Fredy himself was deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto in December 1941. The Jewish functionaries who administered the ghetto put him and another man in charge of Youth Welfare. In the coming months, thousands more Jewish families were imprisoned in Theresienstadt.

———

Helga Ederer: I was put into a girls’ children’s home. It was bunk beds in, in three tiers, and, um, girls of approximately the same age together. And, um, I stayed in the girls’ home for some time, but, um, I picked up all the illnesses there were, I had everything that was going. What was nice about it, we were taught something about Jewish history—although real teaching was strictly forbidden, but it, it went in form of stories and dances and so on. Our self-consciousness was, uh, uh, uh, increased manyfold and, uh, it did raise our hope and our strength.

I do remember the leading personality, uh, who was always, um, in charge of all youth activity was Fredy Hirsch, who was a German Jew. His, his Czech was atrocious. But by speaking German and dressing more or less like a Nazi, which was funny—he always had high polished boots and riding britches—and I suppose, uh, that was one thing which, which the Germans appreciated, that, uh, he, he was on the same level and therefore got their ear very often. And that’s how we were allowed to have little squares where we could play and dance, and I don’t know how we managed to get some balls to play games and so on. We had quite a good time when we weren’t ill.

Yehuda Bakon: He arranged a place for me in the youth or the children house L 417. Not all children were lucky and came into this children home. This children home were designed for children about 12 and about 15 or so. As I was a gifted child, I got all the encouragement through Fredy Hirsch. I could meet all the artists who supported me with pencils, paper, and, uh, critic, and teaching.

JS: He was very, very helpful to me, very specifically, for example. We had a particular job in Theresienstadt to, uh, get the belongings of the deceased and bring them to a particular part of, uh, a warehouse. Now I knew what was happening to these, uh, things, you know, all the, the, the power elite took it and, and, and enjoyed it. And I say, hey, you know, I’m going to get a piece of action here. And, and so I took some piece of soap and, and some books. And someone—some sort of big wheel or whatever, small wheel—saw it out the window and, and, and, and, and stopped us and called the, the ghetto police and whatever. And we went into terrible trouble. And Fredy Hirsh got us out of the trouble and said, “I’m going to see to it that they’ll be punished.” And he punished—so we had to clean the toilets, big deal. And other than that, we would’ve been in terrible trouble. I mean, you know, deportation possibly, this, you name it. That was Fredy Hirsch.

Melitta Stein: In 1943, the regular transports to Auschwitz started because now people came, the Jews from almost entire occupied Europe, came to Theresienstadt and it was filling up and it didn’t have that capacity. In order to fulfill Hitler’s dream to get rid of all Jews, they started these transports to Auschwitz, where there were gas chambers.

Eva Gross: Fredy went with the, with the September transport—Fredy Hirsch, who was important in all our lives and who did an awful lot of good. He went, he was gone.

———

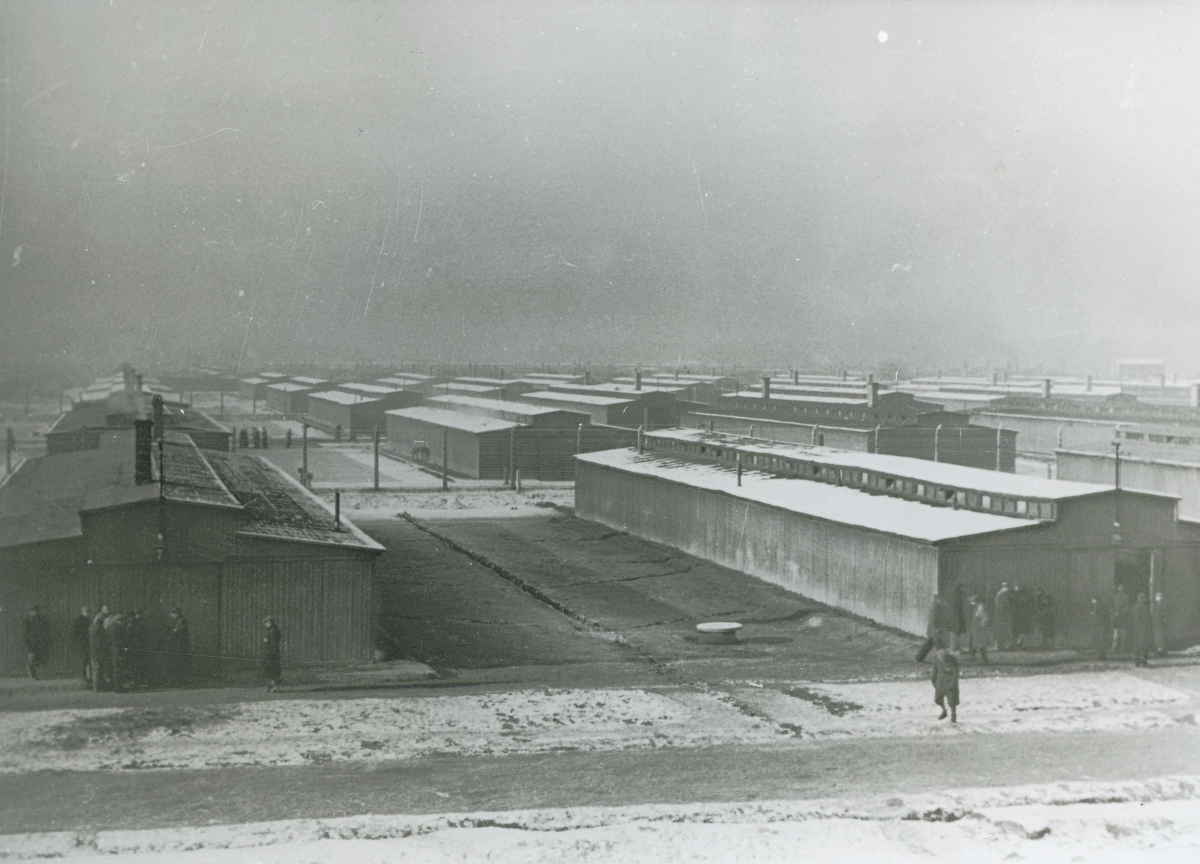

EM Narration: Fredy arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau in September 1943 with five thousand mostly Czech Jews transported from Theresienstadt. Unlike the vast majority of Jewish prisoners in Auschwitz, they weren’t subject to selection upon arrival—meaning the elderly, children, and the sick were not singled out to be gassed immediately. Instead, the entire group was housed in Lager BIIb, or what came to be known as the Czech family camp.

Conditions in the family camp were slightly better than in other parts of Auschwitz, though many of the adults were forced to perform slave labor and died doing so. Fredy persuaded the SS to create a daytime children’s barracks and to let him oversee it.

Three months after Fredy’s transport arrived, another transport of five thousand Czech Jews from Theresienstadt was brought to the family camp.

———

MH: I was taken to a Jugendheim and who, who should be running the Jugendheim but Fredy Hirsch. So Fredy laughs, you know, it’s a big joke, and he says, “Ah, du bist schon da.” Like, “At last, you’re here,” you know, “I’ve been waiting for you.” And everybody’s laughing, you know, because—and this was his, his method to prevent the children from being afraid.

In this godforsaken place, he somehow got permission to get all the small children into a Jugendheim, and he did in Auschwitz-Birkenau, in the family camp, what he did in Theresienstadt. He took the children into a space where the space wasn’t prison. They started drawing paintings on the wall, and they were divided into groups, and each group had a madrich. And they were told stories and they were singing songs and there was a choir.

EG: I got dysentery and I was out. The first Appell, when we stood in, uh, ice cold, I fainted, and luckily I was, uh, taken in, into the barracks and they counted me in. And when I became feeling better, I remember suddenly Fredy Hisch standing near me, pulling me out, and said, “Come on,” and taking me to what was a children’s barracks—without beds, but lots of tables, and there were children, children, children, and I was so relieved and immediately much better.

RT: Very soon after I arrived, we, I started to work in that children’s barrack that Fredy, uh, got for the children. Some of them were, I think, four years old, uh, five years, seven, ten. I don’t think they were aware what’s actually happening. And I think the allowed age was 16, up to 16. Anybody over 16 was considered an adult, right?

But since, uh, Fredy knew me and since, uh, I was just close over 16 only, he wanted to spare us kids us, of my age of, from the normal adult life there, which was, uh, very, very difficult and horrifying, really. And so he let me, like, work in the children’s barrack, although the only thing I did was that I was carrying the barrels with the children’s soup at lunchtime back and forth from the kitchen, and the rest of the day I was just joining the kids like everybody else.

Uh, we were trying to do some singing groups, some theater groups, some reading groups. Fredy also, uh, got some allowance of books—children’s books, fairytales and things like that.

Chava Ben-Amos: It was a Familienlager. It wasn’t food, it wasn’t fun. But what we did have was some kind of an education. We would sit on the heating thing. They divided us by age groups or something, and people would teach us. And I learned about poetry, I learned about music. Somebody told us how movies are made. I remember in, in smallest detail what they taught us there. We also had all kinds of competitions between the children, like you were not allowed to speak for three days at all. Not one word. I remember that I lost the game because I woke up one morning and said “Good morning” to somebody.

They tried to keep us busy and Fredy Hirsch was coming and organizing it. I also remember that he called all the children at one time out, outside, and he was teaching up, us about self-hypnosis. He was lecturing us that if we suffer from anything, if something hurts, if we are hungry, we can help ourselves by telling us, telling ourselves it isn’t so. If we have pain, we say the pain is going away, it’s going away, it’s going, and it’s gone. If I was hungry, I was telling myself I wasn’t—it’s going away, it’s going away. I was doing it—I can still do it today.

YB: Now the organization of our daily life was much better because of Fredy Hirsch, and slowly he managed to got many better condition. One of them, the formidable thing is that we could have our so-called Appell, counting, inside the block. The normal way was twice a day counting, which was a terribly torture—we were put out in, in all conditions. Anyhow, he arranged for us to be counted in the block, which saved us from many death. Secondly, he got better treatment for us. Better food, special rations.

RT: He in Auschwitz got the courage to talk back to the Germans, which was unheard of and, I mean, crazy thing to do. But he did it and he succeeded with that, because he spoke to them as they spoke to him, in a military way, and they very much liked that. You know, that impressed the Germans really.

YB: His way of education, to keep us trained, to make, um, exercises. And if we were a bit dirty, he looked in our nails, and he, um, forced us to wash ourselves, even with snow. And I remember, we had not a towel—a group of 20 children had a handkerchief. There was hardly any water running. But his drilling in a way saved our life. Because in Auschwitz, the people had a better chance to survive if they looked more or less still human.

If you looked, starting to be what we called a Muselmann, or you had a little rash, that would mean you go to the gas chambers on the next—or you got much worse treatment than somebody who still looked half-human. And that’s thanks to Fredy. One of the many reasons why we survived is because he drilled us to keep fit even in these circumstances. Because who wanted in Auschwitz to wash himself with snow?

———

EM Narration: That winter, many of the children’s parents and grandparents died of hunger, disease, and exhaustion.

In the early months of 1944, a rumor circulated that the prisoners in the family camp were going to be moved to a work camp called Heydebreck.

But Auschwitz had a resistance movement that had access to the Nazis’ files, and they had reason to believe that the Czech families were actually destined for the gas chambers. Hoping to incite a revolt, the resistance sent a go-between to the family camp to relay their suspicions.

———

Rudolf Vrba: I was given the task to inform the resistance movement within the family camp that the possibility of them being gassed on the March 7 is perfectly real, although not yet fully confirmed. I was supposed to transfer this information, this possibility is real. I contacted Fredy Hirsch, who was sort of a potential for a leader of a revolt.

Where the attack should take place was not so clearly formulated because it was not yet clear if they are going to be gassed. But the whole possibility of an uprising within the camp was first time seriously considered. It was explained to those Czechs that they are going possibly to die.

So, uh, Fredy Hirsch, uh, objected. Uh, he, uh, was very reasonable. He said that it doesn’t make sense to him that the Germans would keep them for six months and feeding the children with milk and white bread in order to gas them after six months. And after all this, uh, personal relationship, which he managed to struck up with a number of the officers. And, and that they wouldn’t allow it because there was already a personal relationship between the SS, uh, and, and those children.

JS: Then came the terrible thing that all a sudden certain people with certain numbers had to go, uh, and be, uh, uh, be separated, taken away so that all the people, they went and control people with certain numbers—which was just exactly the number of Fredy Hirsch.

———

EM Narration: On March 7, Fredy and the other surviving Jews from the first transport were moved from the family camp to the adjacent quarantine camp.

———

CB: When they took the transports of the children that he was most involved with, they gave him the option of not going with them. He went because he didn’t want to leave them alone. We all were completely flabbergasted because we heard that he was allowed not to.

MS: We were witnesses as they were rounded up, taken by trucks to a neighboring camp, where we could see them because it was only wires that divided the camps. We could see them, but we couldn’t do anything.

RV: On the next day I got the message, again from the resistance, that it is sure that they’re going to be gassed, that the Sonderkommando already received the call for burning the transport. Everything was organized. I mean, this was not just a disorganized sort of, uh, uh, sort of slaughterhouse. It was an organized slaughterhouse, and that was, the organizations were made for this particular transport.

So now my task was again to explain to Fredy Hirsch the situation. So I explained to him that as far this transport is concerned, included him, they are going to be gassed on the next 48 hours. And that, uh, the situation being what it is, it is necessary to hit now. This is a chance which doesn’t, never occurred before, to have such an informed group in front of the gas chambers.

So he suddenly started to worry. He said, “What happens to the children if we start the uprising?”

UP: Fredy knew when the Familienlager was going to be eliminated. And they went through this terrible agony, whether they should inform everybody and fight back in some way, and, you know, and cause a tremendous disruption. All you could do is cause a disruption, because you had machine guns from all corners—I mean nobody could have any illusion that they could survive.

Fredy and some of the other people came to the conclusion that if they will do so, they would cause such bedlam and such fear, and nobody was going to be saved anyway, and the children, instead of going into the gas not knowing where they were going, they were going to be, you know, like hunted animals.

HE: So he refused to lead the, uh, um, revolt, which was planned. And I do know that there was some kind of resistance was planned because I remember seeing one man with, with, uh, wire cutters and, and, uh, lots of people getting together talking about possible resistance, but nothing came of it.

———

EM Narration: Shortly after Fredy received confirmation from the resistance that his entire transport would be murdered, he was found in a coma. It’s not clear whether he overdosed by accident on tranquilizers, was poisoned by doctors who feared for their own lives if he led a revolt, or whether he tried to kill himself. That same night, the SS carried out its plans.

———

EG: They loaded them up on trucks and they took them over to the crematorium. By then they of course knew what was happening and three—they sung. They were singing. They were going to their death singing, one group singing the Czech anthem, one group singing the “Hatikvah,” and the third one “The Internationale.”

RT: They loaded them on trucks, you know, and they disappeared. And we learned that they were gassed. The whole transport was gassed. All half of our camp—children, adults, everything—half were gassed.

———

EM Narration: Fredy and about three thousand seven hundred other Jews, including many of the children who’d been in Fredy’s care, died on March 8, 1944.

In July, the Czech family camp was closed. Four thousand people were put to death. The remaining three thousand were sent to work camps. Among them were some of the people you heard in this episode:

Dina Gottliebova-Babbitt, Michael Honey, Ursula Pawel, Rene Tressler, Peter Mahrer, John Steiner, Helga Ederer, Yehudah Bakon, Melitta Stein, Eva Gross, and Chava Ben-Amos. Rudolf Vrba was the Auschwitz resistance go-between.

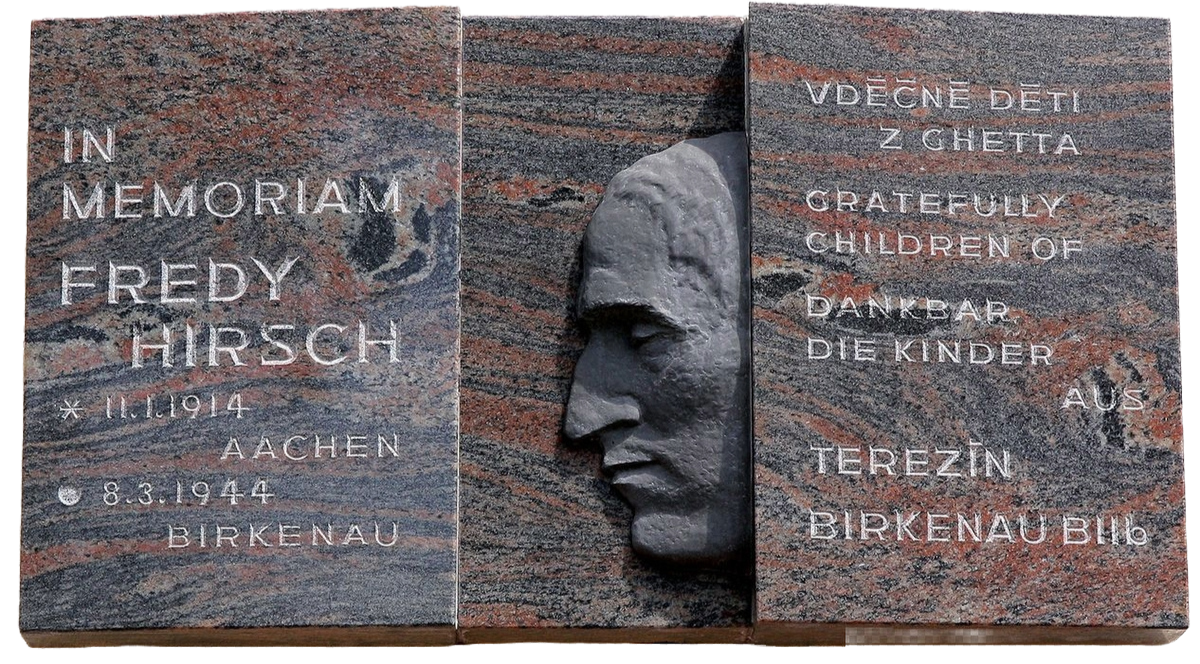

In 1996 a group of survivors of Theresienstadt and Auschwitz-Birkenau arranged for a stone plaque to be installed in Fredy’s memory in Theresienstadt. They gathered for a ceremony to honor the young man who died in Auschwitz at the age of 28. The plaque reads, “In Memoriam: Fredy Hirsch. Gratefully, The children of Terezín, Birkenau BIIb.”

———

Up next: the epilogue to our “Nazi Era” series.

———

This episode was produced by Nahanni Rous, Inge De Taeye, and me, Eric Marcus. Our audio mixer was Anne Pope. Our studio engineer was Elvira Gutierrez at CDM Sound Studios. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Thank you to our photo editor Michael Green, our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham, and our founding production partner, Jenna Weiss-Berman.

The segments of the interviews with Dina Gottliebova-Babbitt, Michael Honey, Peter Mahrer, Helga Ederer, Yehudah Bakon, Melitta Stein, Eva Gross, and Chava Ben-Amos are from the archive of the USC Shoah Foundation—The Institute for Visual History and Education.

The oral history excerpts of Ursula Pawel, John Steiner, and Rene Edgar Tressler are from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection. The Pawel testimony is provided courtesy of the Jeff and Toby Herr Foundation; the Steiner testimony is a gift of the Jewish Family and Children’s Services of San Francisco, the Peninsula, Marin and Sonoma Counties.

The Rudolf Vrba audio was drawn from footage created by Claude Lanzmann during the filming of Shoah and was used by permission of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Martyrs and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority in Jerusalem.

To learn more about the people and stories featured in our episodes, please visit makinggayhistory.org, where you’ll find links to additional information and archival photos, as well as full transcripts.

This special series on the experiences of LGBTQ people during the rise of the Nazi regime, World War II, and the Holocaust is a production of Making Gay History, in partnership with the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale University.

I’m Eric Marcus. Until next time.

###