Morris Foote

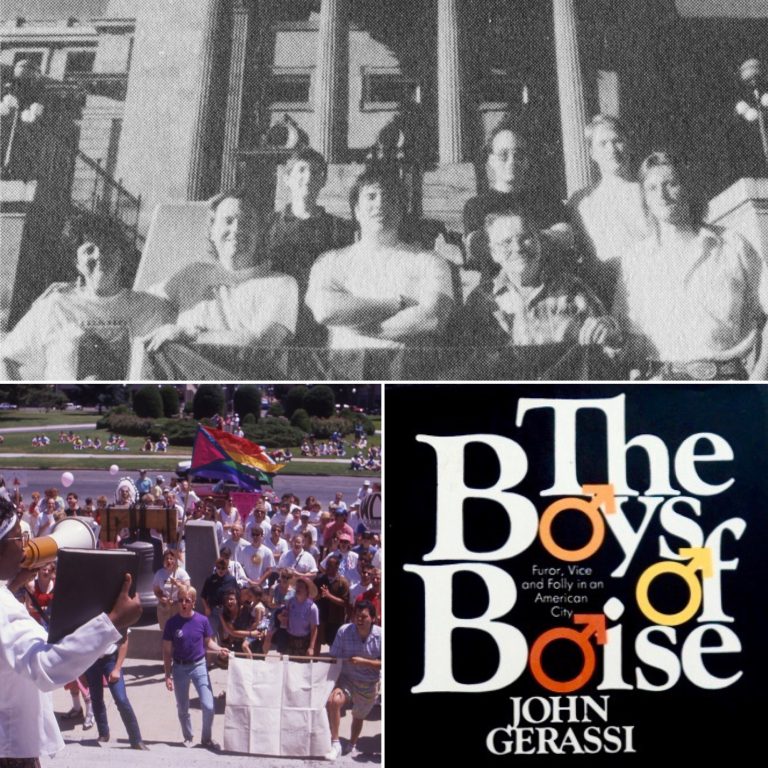

From top clockwise: Standing on the steps of Idaho’s capitol building is a clean-shaven Morris Foote (front row, second from right) with the organizers of Boise’s first Gay and Lesbian Freedom Parade and Festival, which was held on Saturday, June 23, 1990. Credit: © Troy Maben; book jacket from John Gerassi's 1966 account of the Boise homosexual panic; Rev. Carolyn Mobley (at left with megaphone) teaching marchers songs and chants prior to the start of the 1990 Freedom Parade. Credit: © Troy Maben

From top clockwise: Standing on the steps of Idaho’s capitol building is a clean-shaven Morris Foote (front row, second from right) with the organizers of Boise’s first Gay and Lesbian Freedom Parade and Festival, which was held on Saturday, June 23, 1990. Credit: © Troy Maben; book jacket from John Gerassi's 1966 account of the Boise homosexual panic; Rev. Carolyn Mobley (at left with megaphone) teaching marchers songs and chants prior to the start of the 1990 Freedom Parade. Credit: © Troy MabenEpisode Notes

When Boise, Idaho’s “homosexual panic” was ignited in the pages of the Idaho Statesman newspaper in November 1955, Morris Foote was a 30-year-old elevator operator at Idaho’s state capitol building. He had no idea that what he’d been doing with other consenting adult men could get him arrested. But after reading about the first arrests of homosexual men and allegations of a homosexual ring involving a group of adult men and 100 teenagers, Morris Foote wasn’t going to wait around to see what happened. He left Boise for his hometown of Middleton, Idaho, and didn’t set foot in Boise again for more than two decades.

According to the late journalist John Gersassi—whose 1966 book, The Boys of Boise: Furor, Vice and Folly in an American City, chronicles the scandal—the police questioned nearly 1,500 Boise citizens and gathered the names of hundreds of suspected homosexuals by the time the investigation ran its course the following year. All told, 16 men were arrested on charges ranging from “lewd and lascivious conduct with minor children under the age of 16” to “infamous crimes against nature.” Of the 16, 10 went to jail, including several whose only crime had been to engage in sex with another consenting adult male.

According to the late journalist John Gersassi—whose 1966 book, The Boys of Boise: Furor, Vice and Folly in an American City, chronicles the scandal—the police questioned nearly 1,500 Boise citizens and gathered the names of hundreds of suspected homosexuals by the time the investigation ran its course the following year. All told, 16 men were arrested on charges ranging from “lewd and lascivious conduct with minor children under the age of 16” to “infamous crimes against nature.” Of the 16, 10 went to jail, including several whose only crime had been to engage in sex with another consenting adult male.

During the years Morris Foote spent in self-imposed exile he worked as a farmer and lived just down the road from the house where he grew up. In the late 1970s, after hearing about a gay bar in Boise, he returned to the city from which he’d fled and made his way into the LGBT civil rights movement through the Metropolitan Community Church (MCC), a Christian church whose membership is primarily LGBT.

In the early 1980s, Morris attended his first public protest against the virulently anti-gay Rev. Jerry Falwell and in 1990, as a board member of Your Family, Friends and Neighbors, helped to plan Boise’s first Gay and Lesbian Freedom Parade and Festival, which was held on Saturday, June 23, 1990.

———

For a comprehensive look at the 1955 Boise homosexual panic, have a look at John G. Gerassi’s 1966 book, The Boys of Boise, Furor, Vice and Folly in an American City.

On the 60th anniversary of the Boise scandal, the Boise Weekly published a look back at the city’s “notorious LGBT crackdown.”

Seth Randal produced a 2006 documentary about the Boise scandal called The Fall of ’55. You can watch the film’s trailer here and read an in-depth interview with the film’s director here.

To learn more about the Metropolitan Community Church, which was central to Morris Foote’s journey into Boise’s LGBTQ community and activism, click here.

In this episode Morris mentions Rev. Freda Smith, who gave a memorable speech at a protest rally Morris attended. To learn more about Rev. Smith, click here.

Another story about anti-gay hysteria is chronicled in Neil Miller’s Sex-Crime Panic: A Journey to the Paranoid Heart of the 1950s.

The New York Times published an opinion piece in 2007 that used Idaho Senator Larry Craig’s 2007 bathroom sex scandal as the jumping-off point for revisiting the 1955 Boise panic.

To get a better sense of the anti-gay hysteria of the 1950s, have a look at David K. Johnson’s 2004 book, The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government. Read a summary of the book here. In our episode featuring Hal Call, Hal talks about the “ogre” communism was perceived to be at that time and how it affected the Mattachine Society.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

When I did the original research for my oral history book back in the late 1980s, I was determined to tell the story of the LGBTQ civil rights movement beyond New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Every city, as I came to discover, had its own history and stories as the gay rights struggle spread across the country.

And that’s how I stumbled across Boise, Idaho’s 1955 homosexual panic. There’s no other way to describe it. John Gerassi, a journalist, wrote about it in his 1966 book, The Boys of Boise. As he explained, it all started with the arrest of two men on morals charges and the false claim by a Boise probation officer that about a hundred boys were involved in a homosexual ring. As the phony scandal unfolded over several months, the police questioned nearly 1,500 Boise citizens—in a town that had only 40,000 residents. They gathered the names of hundreds of suspected homosexuals, many of them in heterosexual marriages.

In the end, 16 men were arrested. Ten went to jail. For most of them, their only crime was engaging in sex with another consenting male. I found it hard to imagine what the lasting impact was on Boise’s gay citizens and the families of those men whose lives were upended by a senseless witch hunt.

I had to go to Boise. But the challenge was finding someone who was gay, who remembered what happened, and who would talk to me. In 1989 this wasn’t exactly a piece of Boise history that anyone was proud of and wanted to revisit, whether they went to jail or just watched from the sidelines. So I called Boise’s gay community center and explained what I was looking for. They had one name for me—Morris Foote, a retired farmer who lived in Middleton, Idaho about a half hour northwest of Boise.

Morris was a World War II veteran, who was born on June 11, 1925 in Caldwell, Idaho. At the time of the homosexual panic, he was working in Boise’s capitol building as an elevator operator.

I called Morris and we made a date to meet at the cafe next to where he lived. There was one condition. We couldn’t talk about anything gay during lunch. That would have to wait until we went back to his house. Morris didn’t want to risk anyone overhearing our conversation so close to home.

Two months later, I’m on a plane to Boise. It would be my first time in Idaho.

So here’s the scene. Morris’s directions take me to a street just a block from the center of Middleton. It’s a sleepy farming community that’s clearly seen better days. I pull up in front of Morris’s green mobile home, which sits on the same lot as a pawn shop and a pint-sized cafe. I step out of my rental car and take in the landscape. A few one-story bungalows. Some well kept. Some not. And as far as the eye can see there’s a lot of empty space and it’s very, very flat.

I walk over to the cafe and that’s where I find Morris, his friend Sammy, and Morris’s younger brother, who has severe cerebral palsy. Morris had explained to me that his brother moved in with him after their mother died. And he wanted his friend Sammy there for support.

Morris is a compact, heavy-set man. He looks like a retired Amish farmer out of central casting, with a long white beard and old-fashioned glasses. Over iced tea and sandwiches we talk about everything—except what I’m there to talk about.

An hour later, we each take our places in Morris’s cramped living room. I clip my microphone to the strap of Morris’s overalls, settle back into a well-worn easy chair and press record.

———

Eric Marcus: Interview with Morris Foote. Thursday, November 16, 1989, 2:30 p.m., at the home of Morris Foote in Middleton, Idaho. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Tape one, side one.

What was Boise like at that time? Was it a busy town with lots of bars or…?

Morris Foote: Main Street was skid row. You wouldn’t recognize it now. You see what is now is the Egyptian Theater. Across the street was bar after bar after bar after bar after bar. And you’d go into some of the bars and very plentiful homosexual activity right in the restrooms. Opened. It was too opened. They were just asking for trouble.

EM: So, if you met someone at a bar, you’d have sex there. You didn’t go back to someone’s house, did you?

MF: Oh, you wouldn’t have sex with anyone except in the bar, noooo!

EM: Well, what did you do then? I don’t know…

MF: You went to the bathroom and took a leak and then someone come up to you and said, “Would you like to have it?” And then you’d go back to the bar and you’d never see the guy again.

EM: And you wouldn’t talk to each other.

MF: No, never see the guy again.

EM: Did you have any sense that being gay was bad at the time?

MF: Absolutely not. One time, about 1955, The Statesman put an editorial out that all homosexuals must… activity must cease. And it was a sin of society. And there was a homosexual ring operating in Boise and it must be put down.

I looked at that and said, is that act illegal? Here they had the men in jail on felony warrant and was going to send him to the pen for the rest of his life for doin’ it. I thought that anytime you had sex in privacy, no one would bother you. As long as it was an adult. It was two adult men.

EM: Do you remember seeing the headline that day when it first broke, about the arrests?

MF: Mmm-hmm.

EM: What did you think?

MF: Well, I think I better move out of Boise and not be around there anymore.

EM: Did you get calls from friends of yours who were being picked up or people who were being questioned?

MF: No. No one knew me.

EM: No one knew you.

MF: Uh-uh. You don’t tell your name. And I don’t know their name.

EM: Uh-huh. During that whole investigation, did you ever go into Boise at all?

MF: Not after that.

EM: Why didn’t you go?

MF: Well, I just decided I wouldn’t be a part of it.

EM: Because?

MF: I didn’t want to go to the penitentiary.

EM: That’s a good reason.

MF: And I still don’t know when the statute of limitations are now. Whether I told you I had sex with someone, whether I could still be put in court on it. I don’t know. Do you know what statute of limitations…? I don’t know.

EM: I don’t think… seven years.

Growing up in high school did you know any other kids who were gay? Or did you even know what gay was?

MF: I didn’t even know what I was.

EM: Did you know you were different?

MF: No.

EM: Did you think about it at all?

MF: No.

EM: No crushes on boys?

MF: Always went around with boys. But during that period of growing up, that’s customary for boys to go with boys in high school. I went with a boy from about seventh grade all through high school, through college.

EM: The same boy?

MF: Uh-huh.

EM: So he was your best friend.

MF: Yeah, we owned property and owned a car together. Just before graduating college, why, he took me aside and then he told me what I was. I didn’t know. He wanted sex. I never had any sex.

EM: With him?

MF: Hmmm.

EM: All those years.

MF: Hmmm. So he propositioned me and told me what I was, explained what a gay homosexual was. He said I was one. And I had just taken abnormal psychology, the study of those things. But in that book only about a paragraph on homosexuality said about three percent of the population had it. It went right on… It hardly mentioned it in the textbook. I bet today there’d be a lot more on it.

EM: And you hadn’t heard of that before, homosexuality?

MF: Didn’t pay much attention to it. Till he explained it, because he went off and got married.

EM: To a woman.

MF: Oh, yes.

EM: And he was… Was he gay?

MF: No, he’s straight. He had probably had some fun in the Navy. So then I got interested and started going to Boise finding boyfriends.

EM: Did you miss him?

MF: I miss him all my life. One of the saddest things, last year went to his funeral. They had a private interment, but they notified me. They wanted me to be present. And I was honored.

EM: Did you see him during all these years?

MF: About twice or three times.

EM: Did he know how much you loved him?

MF: I think so.

EM: Yeah. That just makes me sad. That’s sad.

When did you start hearing about other places having gay rights groups and marches and all that business?

MF: Oh, probably after the gay community in Boise started. The gay bar opened in ’77. Started going to Boise again.

EM: After, that’s after… That’s 20 years later.

MF: That’s right. It wasn’t like the old Indanha downstairs nor The Gas Light, where you never seen a homosexual picture and there wasn’t any gay talk at all or anything. This was strictly gay. You knew what you entered into.

When the gay movement got started, I considered myself part of it. Right, the very first time here in the bar. Then I got invited to join the gay rap group.

EM: Why did you join the gay rap group?

MF: Socialize. Meet other gays. It’s a wonderful time to get together.

EM: When did you join MCC?

MF: Metropolitan Community Church, 1978. When it started.

EM: Why did you join?

MF: Because I like evening worship service. I’ve always liked evening worship service. Of course, being my sexuality, that feel right nice. And moved right into it.

EM: When did this march come about? The gay group and MCC didn’t protest much out in public here in Boise or Middleton, did it? It was kind of private, I would think.

MF: You mean when we marched on the state capitol? We were having a district convention. Just before our meeting, two days before, I think, the Reverend Jerry Falwell scheduled a rally on the state capitol steps.

EM: Why did he do that?

MF: He was going to every state capital at that time. I think he was trying to organize a political party. I’d say ’82, ’83, along in there. So a lot of us gays went to the Jerry Falwell Crusade.

EM: So you went to his talk?

MF: Oh, yes. You always want to go to the opposition and see what they have to say.

He spoke so much against homosexuality. Then when the convention started, then they decided, voted, let’s have a march to counteract what we had heard a day or so ago. We’ll have it at 11:00 p.m. at night, so those that don’t want to be on camera, they can kind of shy away. So no one would lose a job or anything over it. And they had 500 march.

EM: Were you worried about marching at all?

MF: No. Not at all. One thing, you couldn’t be seen on TV. Just a mass of humanity out there. That was the march. And Rev. Frieda Smith, who was borned in Pocatello, and is one of the elders in the church, gave the most wonderful talk that night on the state capitol.

EM: Do you remember any of what she said?

MF: “The word is out that we are human beings, too. We should have our rights, too.”

EM: What do you think the rights of gay people should be?

MF: Equal rights. I think one thing we need to do that sexual acts among two consenting adults done in private should be legal. But I don’t think it’ll get anywhere now with the AIDS epidemic.

EM: I hear talk about a gay pride march this spring?

MF: Oh, someone wrote in the paper they’d have one, but I don’t know…

EM: Are you in favor of a parade?

MF: Yes, I guess so.

EM: Why do you say that you guess so?

MF: I don’t know whether I’d be here or not. I would probably be in San Francisco.

EM: How come?

MF: 300,000 to about 30 people.

EM: You mean there will be 30 people at this march.

MF: Yeah. About 300,000 there.

EM: Do you think you’ll go to the parade here?

MF: I don’t know whether it will materialize or not.

———

EM Narration: Despite Morris’s doubts, Boise’s first pride march materialized. And Morris was there after all. And not only was he there, he was one of the organizers! And that’s despite the fact he was still in the closet in his hometown of Middleton. At makinggayhistory.com you can see a photo of a clean-shaven Morris Foote standing on the steps of Idaho’s state capitol holding a rainbow flag in broad daylight along with the rest of the organizers of Boise’s first Gay and Lesbian Freedom Parade and Festival. That was on June 23, 1990. Every time I look at that photo with Morris and the rainbow flag my eyes fill with tears.

When I think about Morris and his journey from the homosexual panic of 1955 to joining the mostly-gay Metropolitan Community Church, going out on a protest march, and helping to organize Boise’s first Pride Parade and Festival, I’m reminded that the fight for LGBTQ civil rights isn’t just the story of dramatic events and major accomplishments. It’s the accumulation of individual acts by people like Morris, like you, and me, too. It’s standing up and being counted and joining with other like-minded people and fighting for shared goals. It’s true that we’re stronger together.

Morris Foote died on December 4, 1998. He was 72. He lived long enough to make his own bit of history.

To learn more about Morris and the Boys of Boise scandal, go to makinggayhistory.com. That’s where you can also listen to all our previous episodes and sign up for our newsletter.

———

I may be the voice of Making Gay History, but without my dedicated team there’d be no podcast. Thank you Sara Burningham, Jenna Weiss-Berman, Casey Holford, Jonathan Dozier-Ezell, Zach Seltzer, and Will Coley. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

We’d also be nowhere without all of you who have helped spread the word about Making Gay History far and wide, from Cambodia to Norway and the Middle East to the Pacific Northwest. We’re grateful beyond words and hope you’ll continue to share what you’ve heard with friends, family, and colleagues.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and the ONE Archives Foundation.

Season two of this podcast is made possible with support from the Ford Foundation, which is on the front lines of social change worldwide.

And if you like what you’ve heard, please subscribe to Making Gay History on iTunes, Spotify, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts.

So long. Until next time.

———

EM: Actually, did you have any questions for me before…?

MF: You were born and raised in New York City?

EM: Yeah.

MF: And you been gay all your life?

EM: Yep.

MF: You’ve never been married.

EM: No. Except to my husband.

MF: [Laughs.] Have you ever faced any persecution, job loss or…?

EM: Uh, other than the usual stuff, no, nothing out of the ordinary.

MF: Can you tell another gay person by looking at him?

EM: Can I? Some.

MF: How do you tell a gay person?

EM: By looking. It’s just… Eye contact, uh, yeah…

MF: What causes homosexuality?

EM: You want the latest studies?

MF: Yes. [Phone rings.] Excuse me one moment…

###