Hal Call

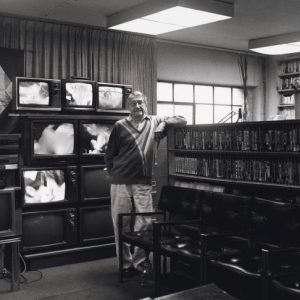

Portrait of Hal Call, 1953. Credit: Harold L. Call papers, ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries

Portrait of Hal Call, 1953. Credit: Harold L. Call papers, ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC LibrariesEpisode Notes

Hal Call was a passionate defender of the rights of gay men, an unashamed supporter of sexual freedom, an out gay man who used his real name at a time when most people in the LGBT civil rights movement took pseudonyms, and he was also incredibly divisive. He led a takeover of the Mattachine Society from the founders in 1953, moved the organization’s headquarters from Los Angeles to San Francisco, and dramatically changed the direction of the nascent “homophile” movement. Hal’s post-Mattachine career was focused on the Circle J, a sex club and porn theater that he owned and ran in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district. Hal died on December 18, 2000. He was 83.

———

In this episode, Hal makes reference to what’s become known as the Lavender Scare, which was the gay analog to the 1950s Red Scare, both of which were led by Senator Joseph McCarthy and, as Hal put it in his interview, the two “fairies without wings,” Roy Cohn and Gerard David Schine (better known G. David Schine or David Schine).

The Lavender Scare is chronicled in a 2004 book by David K. Johnson called The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government. Read a summary of the book here. Learn more about the book here.

Hal also references the Dykes on Bikes, an organization founded in San Francisco in 1976, which you can read about here. And he references Mattachine Society co-founder Harry Hay and Daughters of Bilitis co-founders Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin.

For an in-depth look at the Mattachine Society and Hal Call, have a look at Behind the Mask of the Mattachine: The Hal Call Chronicles and the Early Movement for Homosexual Emancipation, by James T. Sears.

You can also learn much more about the formation of the Mattachine Society from our Making Gay History episode on Mattachine co-founder Chuck Rowland. And you can read Hal Call’s and Chuck Rowland’s oral histories in Eric Marcus’s book Making Gay History.

In 1961, San Francisco public television station KQED aired a groundbreaking documentary, “The Rejected,” in which three members of the Mattachine Society were featured, including Hal Call. Read about the must-see documentary here and here, and watch it here.

Hal helped Life magazine with a landmark article, “Homosexuality in America,” which was published on June 26, 1964.

Hal’s Purple Heart (received when he was wounded in World War II in the Pacific theater) is part of the largest repository of LGBT materials in the world at the ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives in Los Angeles. Click here for a description of what’s in Hal Call’s collection.

The Bay Area Reporter chronicles the history of Hal’s Circle J club in San Francisco at the time of its closing in this 2005 article.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

Hal Call was one of a kind. He was born in 1917 in north central Missouri. He knew he was gay from the time he was 12 and wasn’t shy about chasing after farm boys. He served in the Army in World War II and then went back to Missouri, got a degree in journalism, and went to work for the Kansas City Star. That’s where we’ll pick up the story.

But first, a warning about language and content. If you’ve listened to our earlier episodes, you know I let the people we feature speak for themselves. And I guarantee that Hal will speak for himself. But before you listen, I want you to know that some of what Hal says shocked me at the time I interviewed him and is still shocking to me now. He uses hateful language about women that’s explicit and offensive and some of what he says about the challenges faced by lesbians in the 1950s and ‘60s was simply wrong. But he was also at the forefront in the fight for gay rights and he has an important story to tell.

Here’s the scene—and it was quite a scene because Hal Call’s office was above the Circle J Cinema, which was a sex club and porn theater he owned and ran in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district. I’d only been to a porn theater once before and that was for a bachelor party for a straight high school friend. So I was a bit tentative walking in, but a little curious, too. And I know that because my post-interview notes were unusually detailed.

Hal meets me in the dark entryway and I follow him into the theater, which looks almost like a small chapel. No seats, just pews. I guess armrests would get in the way? There’s a film showing and a couple of men in the audience. We go up a narrow staircase to a spacious, bright office. A long wall is filled floor to ceiling with video cassettes. Another wall is lined with rows of empty vodka bottles.

We sit on a long sofa facing TV screens showing jerk-off films. I’m glad my grandmother is not listening to this episode. As I unpack my tape recorder and microphones I tell myself I’m going to have to avoid looking up because I’ll never be able to keep my train of thought.

Hal is casually dressed in a crisp blue-check shirt, jeans, and stylish glasses. He looks a lot younger than 72. He’s got a ruddy complexion, white hair, and a trim moustache.

There’s a video camera set up on a stand next to where Hal is sitting and it’s focused on me. I clip the microphone to his shirt and he reaches over to his video camera and presses record. I press record, too.

———

Hal Call: You’re running now?

Eric Marcus: Uh-huh.

HC: My name is Harold L. Call and I’m executive director of the Mattachine Society, Incorporated. And your name is?

EM: Eric Marcus.

HC: Eric Marcus. Okay. Do you have any kind of an affiliation or whatever that I should know about?

EM: Uh, no. I’m an independent writer working for Harper & Row on a new book, which doesn’t have a title yet. It’s an oral history of the struggle for gay rights covering the period from 1945 to 1990. And you figure rather prominently in there so that’s why I’m here today to talk to you.

HC: Okay, Eric. Well, let’s get going so…

EM: There was a point at which you were arrested in ’52.

HC: August, yes. I was in a very small automobile. It was a two-seater, but it was a two-door, two-seater Chevrolet or something. Parked at about 1:30 in the morning about 50 feet from the police station in Lincoln Park in Chicago.

EM: How many people were there in the car?

HC: There were four of us. We had gone from a gay bar. They were going to drive me home, but they stopped in the park. But as soon as the ignition, the car was turned off, they were flashing the lights on us.

Three of them thought if they made accusations it would let them get off scot-free and it would put the onus of guilt on another person. Well, those three knew each other and I didn’t know them and they thought they’d walk off scot-free. But they got busted, too, see. All four of us did. And the attorney that we got, he was in with the system and at that time, 1952, $800 bought off the arresting officer, officers, and the judge, and it included the attorney’s fee so that one court appearance brought a dismissal. No conviction. To be accused was to be guilty.

And at that time, I was dumb enough that I didn’t see that there was any harm in telling my supervisor in the Kansas City Star what had happened. He said, “Well, we can’t have anybody like that working for the Kansas City Star.” And I said, “Well, that may be so, okay, but if you fired all the homosexuals on the Kansas City Star, you wouldn’t get the newspaper out.” I told him that. I mean, you couldn’t even set the Linotype at the time.

I decided then that instead of going where the job took me I was going to go where I wanted to and find my own career. So my lover and I drove to San Francisco with all of our possessions and I’ve been here since.

In February 1953 I heard that something called the Mattachine Society out of Los Angeles was having meetings and discussion forums in Berkeley near the University of California campus. And they were getting together to figure out things they could do to help resist this awful thing that we had to face, and that was cops that were chasing us and playing cat and mouse with us all the time and at will.

EM: What happened at that meeting? Were there a lot of people there?

HC: No. About 15 or 20 people.

EM: All men at the meeting? There were women, too?

HC: No, it was all men. Let’s get something straight right here, right now. I know that women’s liberation in this country has come a long way and anything that goes on now has to be spoken of in two genders. Male and female, all the time. Now in the days I’m speaking of, these early days of the gay movement, the women weren’t in it. They didn’t have any problems compared to what the male did. It’s only since the movement got going that the women have come forward and, honest to god, it has been an astounding revelation to me. I never expected to see a mile and a half of Dykes on Bikes in a gay parade ever. And believe me, that’s, well that’s too many Dykes on Bikes as far as this old guy is concerned. Okay, that’s all for freedom.

EM: Why do you say that?

HC: Well, because I think the women have been awfully pushy here in the last few years and have sort of taken over in the thing when they don’t need to. They’ve made a concern out of things that didn’t need to be concerns. The police were playing cat and mouse with the guys. The male homosexual, because he was a cocksucker, and because he played with his penis and somebody else’s penis was a threat to the straight male. Females didn’t count.

The only thing wrong about a poor lesbian as far as the males thought was that poor cunt doesn’t know what a good time she could have if I could stick my dick in her. She’s just missing out. Poor thing. And they pitied her.

Now I’m not, look here, I’ve got wonderful friends that are lesbians, and wonderful friends that are women. And Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin of the Daughters of Bilitis, the founders of that organization are wonderful personal friends of mine and have been since 1955, or so, when I met them. As a matter of fact, we printed, on our gay press, down at Third and Mission, the first issues of their lesbian monthly magazine, The Ladder.

EM: You became deeply involved in Mattachine very early on.

HC: Yes I did.

EM: It was first a secret organization. Why did it have to be secret?

HC: That came about because of fear. The core of it was a secret organization. And Senator Joseph McCarthy in Washington, DC, was going around, you know, with a handful of names and addresses of so many people that were in the Senate or in the government in Washington, “And these are homosexuals and these are communists.” And he was putting the fear of god, along with those two queens that were associates of his, you know, at the time, Cohn and Schine. They both turned out to be fairies without wings.

Anyway, McCarthy was doing his thing and spreading fear among homosexuals and among all kinds of people and having lots of time on television and the like and equating the condition of homosexuality with communism. And of course communism at that time was an ogre, was a specter, a demon that we can’t even imagine today.

So, we knew that some of the founders of the Mattachine movement, the inner circle of the Mattachine Foundation, had been rumored to have some communist leanings and maybe connections elsewhere. Particularly one or two of them, Chuck Rowland and another man, and those were among the six or seven people who founded the Mattachine Foundation along with Harry Hay.

We met in 1953 in Los Angeles at 8th and Crenshaw. We had two meetings there a month apart. And on the second meeting we sort of took it out of their hands. We had the bit in our teeth with it, and we were running away with it almost.

EM: How were you doing that? Were your ideas different from theirs?

HC: No, we wanted to see it become an organization and expand and spread, but we wanted to know who was who in it, what our backgrounds were so that we couldn’t find that we had a person in our midst who was going to be, who could be, let’s say, revealed with some kind of ulterior motives and so on and, you know, and disgrace us all.

EM: A communist infiltrator.

HC: Communism was the fear. And we knew that if we got organized and so on and got going into something that the FBI and other government agencies would find out about us and we wanted it so we could stand up and say who we were and what we were about and stand their investigations and not be accused of these other things.

EM: Several of you disagreed in terms of the philosophy of the organization.

HC: We did. In some ways.

EM: Can you tell me what that was about?

HC: I felt that the [Mattachine] Foundation people were sort of pie in the sky, erudite and artistically inclined. Harry Hay, you could never talk to him very long that he didn’t go back, way back in history, generations and centuries to the berdache or to some ancient Egyptian cult or something of that sort. And he was always making Mattachine and the homosexual of today, parallel to some of those things that were in his studies and research.

We saw a need for Mattachine as a here-and-now practical thing, because we were a group of cocksuckers in society that the police were chasing. And they were assassinating character at will and causing all kinds of mischief and expense and damage to us as individuals.

We didn’t want a secret organization. We didn’t want a sub rosa group within our society. And we wanted to see changes brought about, changes in law, changes in public attitudes, research and education done. Changes… research into the realities of sex behavior and to spread those realities so that the whole of society could say ultimately that homosexuals are human beings in our midst and they’re only different in certain ways from the rest of us. And they’re human beings. Leave us alone. We were wanting to see those goals achieved, and by evolutionary methods. Not revolutionary methods.

EM: Tell me what you mean by… how you hoped to achieve that goal?

HC: Well, mainly hoped to achieve it through projects of education and public service and referrals and things of that sort. And by meeting with and telling our stories to people who were doing writing, research, and who had an influence on law and law enforcement, the courts, justice, and people in the academic world and so on.

EM: So your plan wasn’t to go out and lead protests.

HC: No. Not at all. Not at all. We wanted to see it done by holding conferences and discussions, and becoming subjects for research, and telling our story, and letting people in the academic and behavioral science world get the word out about these realities because we were so goddamned dumb as a people about the realities of human sexuality.

Early in our days we had the Mattachine phone number in our telephone book here in the city of San Francisco. And it wasn’t long before the police knew about us because through gay bars that we had in San Francisco back then—not as many by any means as we have now, but we had maybe eight or ten gay bars in 1950, 1953. And the cops were making arrests there and then we were getting calls from a lot of the people they busted to arrange for an attorney, and even to arrange for a bail bondsman, and things like that. Mattachine was doing those things in those early days.

And so the cops found out there was a Mattachine society, a group of queers that was daring to stand up and work on behalf of other queers the police were busting. And the courts and all found it out. And the attorneys found it out. Bail bondsmen knew it and so on. That started the spread of knowledge of the existence of Mattachine in San Francisco.

EM: There was a statement that I read and I’m not sure I understood it. It said, “Mattachine urged homosexuals to adjust to a pattern of behavior that is acceptable to society in general and compatible with the recognized institutions of home, church, and state.”

HC: We did.

EM: What did you mean by that? I’m not sure I understand that.

HC: We knew that if we were going to get along in society, it was our feeling at the time we were going to have to stay in step with the existing and predominant mores and customs of our major society and not stand out as sore thumbs too much, because we didn’t have the strength of tissue paper to defend ourselves.

Keep your sex life very much to yourself, very much in private. And it also meant don’t go wearing heart on your sleeve. We didn’t have sex symbols and gay flags and those kind of things. Wouldn’t dare hold hands on a street. And you couldn’t even put your hand on another person’s shoulder in a gay bar without it being lewd conduct.

We had people in drag who would come out on Halloween. They knew better, but they dared to do it. They knew their chances were they were going to be busted. And the cops could do any damn thing they wanted and chase us around like little quail out in the brush, you know. All we had to do was run and hide.

EM: You were advising people in a way to help them avoid them getting arrested.

HC: Help avoid getting in trouble. Because if you got arrested and your name got in the paper you were going to lose a job, if you had one. In those days The Examiner printed in bold type on the front page the names of every gay person arrested, his age, his address, his marital status, his employment status, and his professional status, if any. And my god, when that happens, and they’re accused of lewd conduct, 647a and all that, that’s sucking cock, man. That’s the filthiest thing on earth. When those things happened, divorces, suicides, wrecked careers, the loss of rental spaces where you were living, and the loss of credit, and all kinds of things resulted from it.

By today’s standards we were a bunch of limp-wrist pussyfoots. But yet, for us in those days, we were out of the closet and it was a very courageous thing, because there were not very many of us there.

EM: Did you think at the time that homosexuality was sick? Was that what the prevailing belief was? Did you believe that then?

HC: No.

EM: No.

HC: I never believed it. I had this philosophy. We’ve been fighting for sexual freedom and, goddamn it, let’s have some. And so what? If you don’t like it, look the other way. Do something else. Do what you want to do. Don’t bother with it. All along it’s been a matter of that, you know, that people are so incensed and concerned about what homosexuals are doing are simply telling me that they are goddamned jealous because they’re not gettin’ enough themselves.

EM: What was the Seven Committee? And I should tell you that a few people have spoken very fondly of the Seven Committee and they haven’t quite explained it, so I thought I’d go to the source and find out what the Seven Committee was.

HC: The Seven Committee is the name of a group that the… within the Mattachine Society comprised of a good many of its board of directors at the time and two or three others. We set it up to arrange social events. And we did it because we said we’d been fighting, we are fighting, for sexual freedom, then, goddamn it, let’s have some. Within responsible limits. So we had some overnight weekend outings down in the redwoods, in Big Sur country. And we had maybe a thing or two up at somebody’s ranch or something up in the Guerneville area and district. Sometimes we even had a few little things in some of our own apartments or quarters or facilities here in the city. And they were just mainly, well, they were sort of all-night fuck, suck, and circle jerks. And we often had cooked food, like beef stew or a pot of American chili or something you could make a big, one-dish pot out of.

And it was a social activities thing under the Mattachine Society, in a sense. But we didn’t want it so that it would ever rub off on Mattachine and, you know, sort of smirch our good name. But after all, we’re gay sexualists and we were fighting for sexual freedom, and that’s what I said. We decided, let’s have some.

———

EM Narration: You heard Hal say that it was only the men who were hounded by the police, that the women didn’t have any problems, at least compared with the men. That is simply not true. Lesbians were frequently harassed, beaten and thrown in jail because of who they were, like Shirley Willer, whose story you heard in an earlier episode. She got slapped around by a police officer simply because the way she looked and the way she dressed made him think she was a lesbian.

Hal had his own perspective on things. He spoke his mind and didn’t care who was listening. I found it hard to look past his words to what he accomplished, but whatever I might think of him, Hal was also a pioneer who took big risks to fight for equality and sexual freedom. Not every LGBT champion is someone I’d call a hero. It’s complicated.

After that first interview with Hal I went back to do a follow-up interview. When I got there, it was clear that he’d confused appointments. Hal thought I was there to be taped for a film. He was sitting on his sofa in a shirt and his underwear and black socks and shoes, and there was a towel and a bottle of lube on the coffee table. Like the last time, his camera was pointing at my seat. Now I can laugh about it. But back then I was mostly creeped out.

Hal Call lived in San Francisco for the rest of his life. He died on December 18, 2000. He was 83.

If you’d like to know more about Hal Call, please visit makinggayhistory.com. That’s where you can listen to all our previous episodes, including our episode with Chuck Rowland, who was crushed when Hal Call took the Mattachine Society away from him and the other founders.

———

We have a small crew here at Making Gay History and everyone goes above and beyond. Thank you to our executive producer, Sara Burningham; our co-producer, Jenna Weiss-Berman; and our audio engineer, Casey Holford. Jonathan Dozier-Ezell created and manages our website. Will Coley is our social media strategist. Making Gay History’s theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division.

Season two of this podcast is made possible with support from the Ford Foundation, which is on the front lines of social change worldwide.

And if you like what you’ve heard, please subscribe to Making Gay History on iTunes, Spotify, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts.

So long. Until next time.

###