Vito Russo

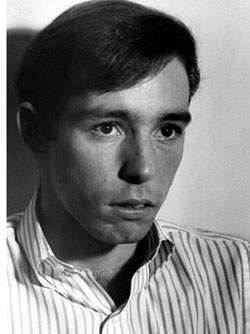

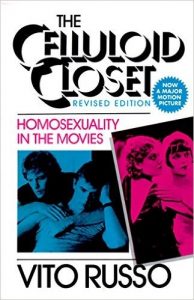

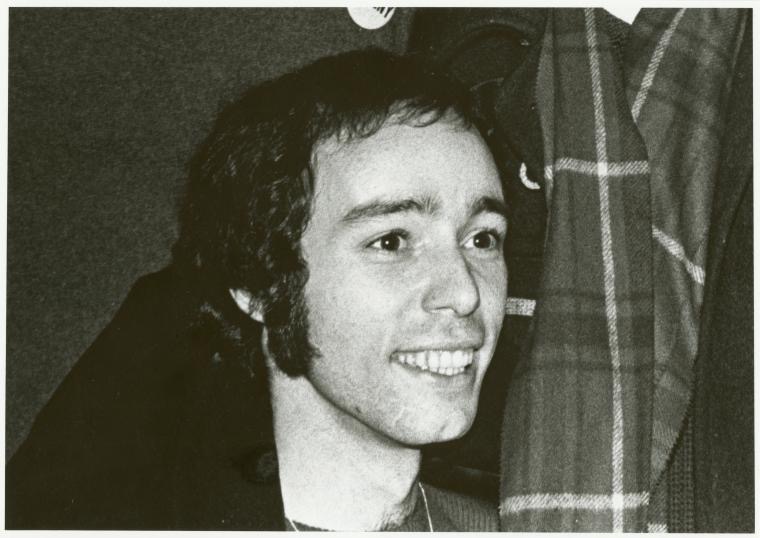

Vito Russo, early 1970s. Credit: New Line Presentations, Courtesy of Charles Russo.

Vito Russo, early 1970s. Credit: New Line Presentations, Courtesy of Charles Russo.Episode Notes

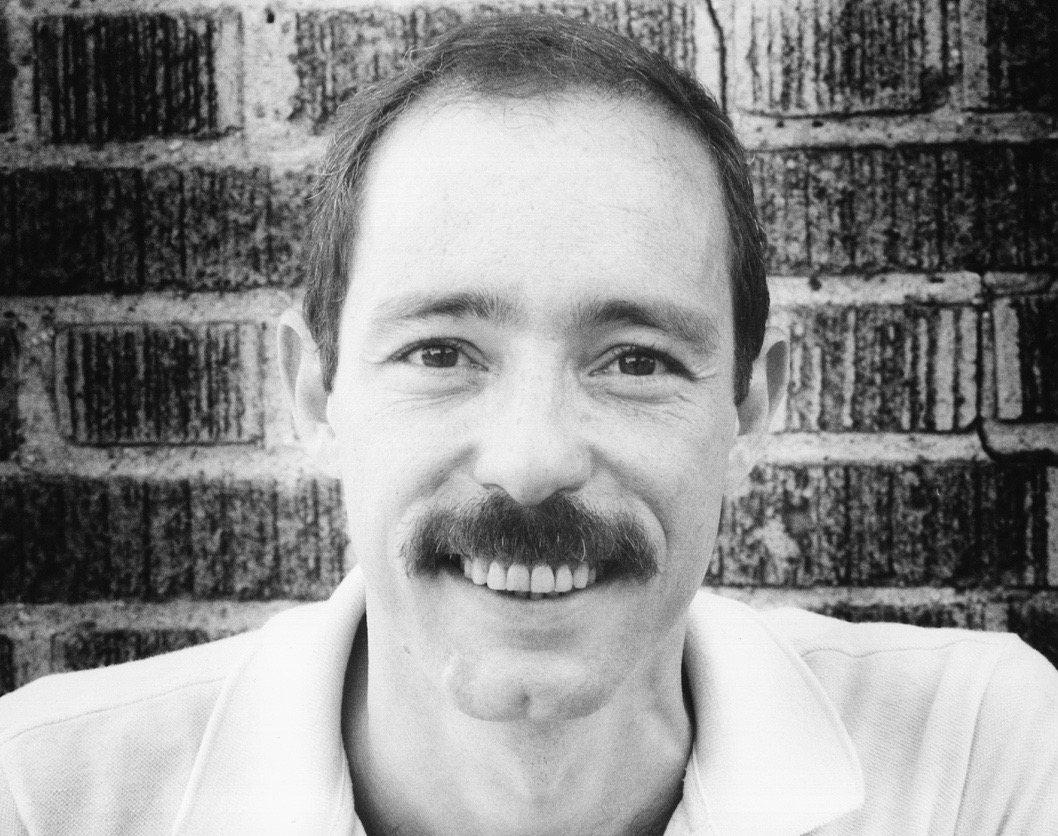

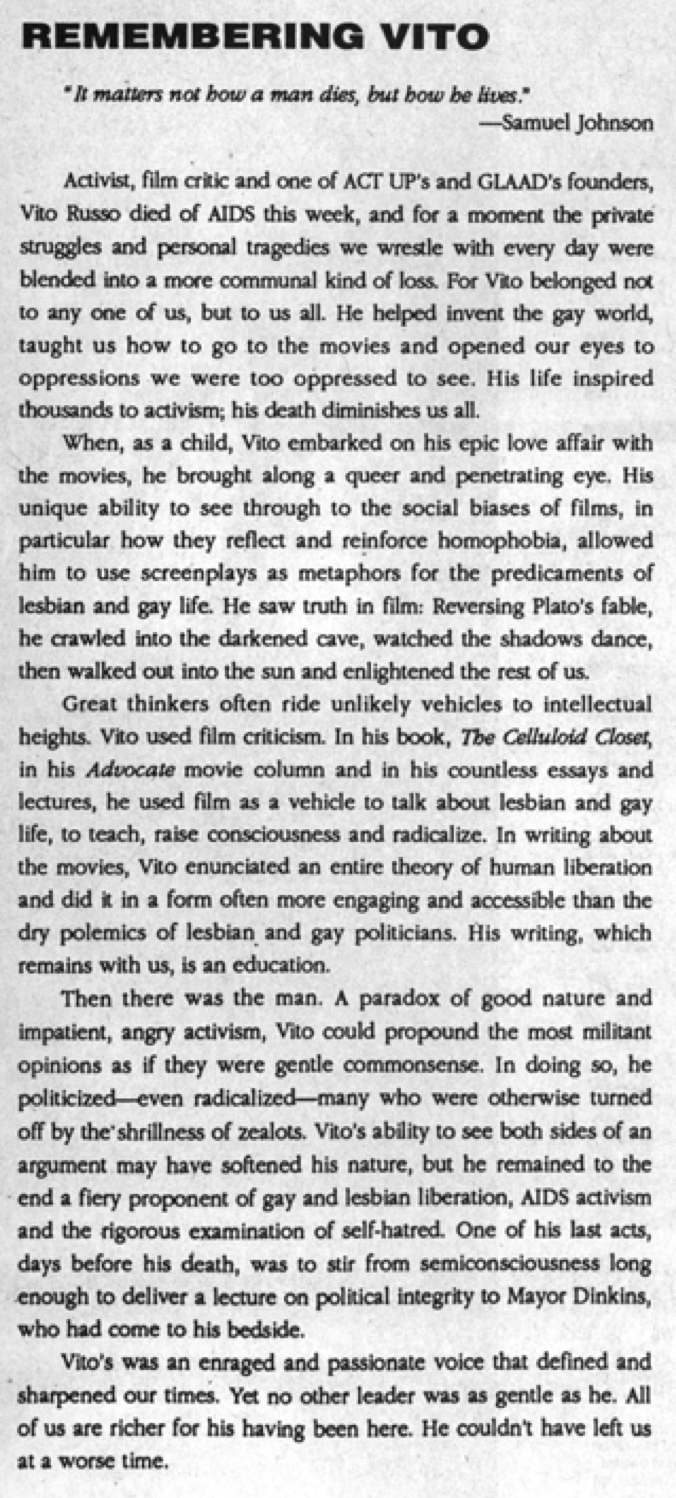

From Eric Marcus: The late author and activist Vito Russo is best known for his 1981 landmark book, The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies, and for co-founding both GLAAD (originally known as the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation), and ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power).

In my interview with Vito, you’ll hear him trace the start of his activism to a candlelight vigil outside St. Vincent’s Hospital for Diego Vinales, who was arrested on March 8, 1970, in a police raid of the Snake Pit bar (in his Making Gay History interview, Vito mistakenly dates the raid to July 1969). Vinales had jumped from the police station’s second-floor window and was impaled on an iron fence. He was taken to St. Vincent’s Hospital, which was then located on 7th Avenue and 13th Street at the northern edge of Greenwich Village. Vito read a flyer that was being handed out at the vigil and that led him to join the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA).

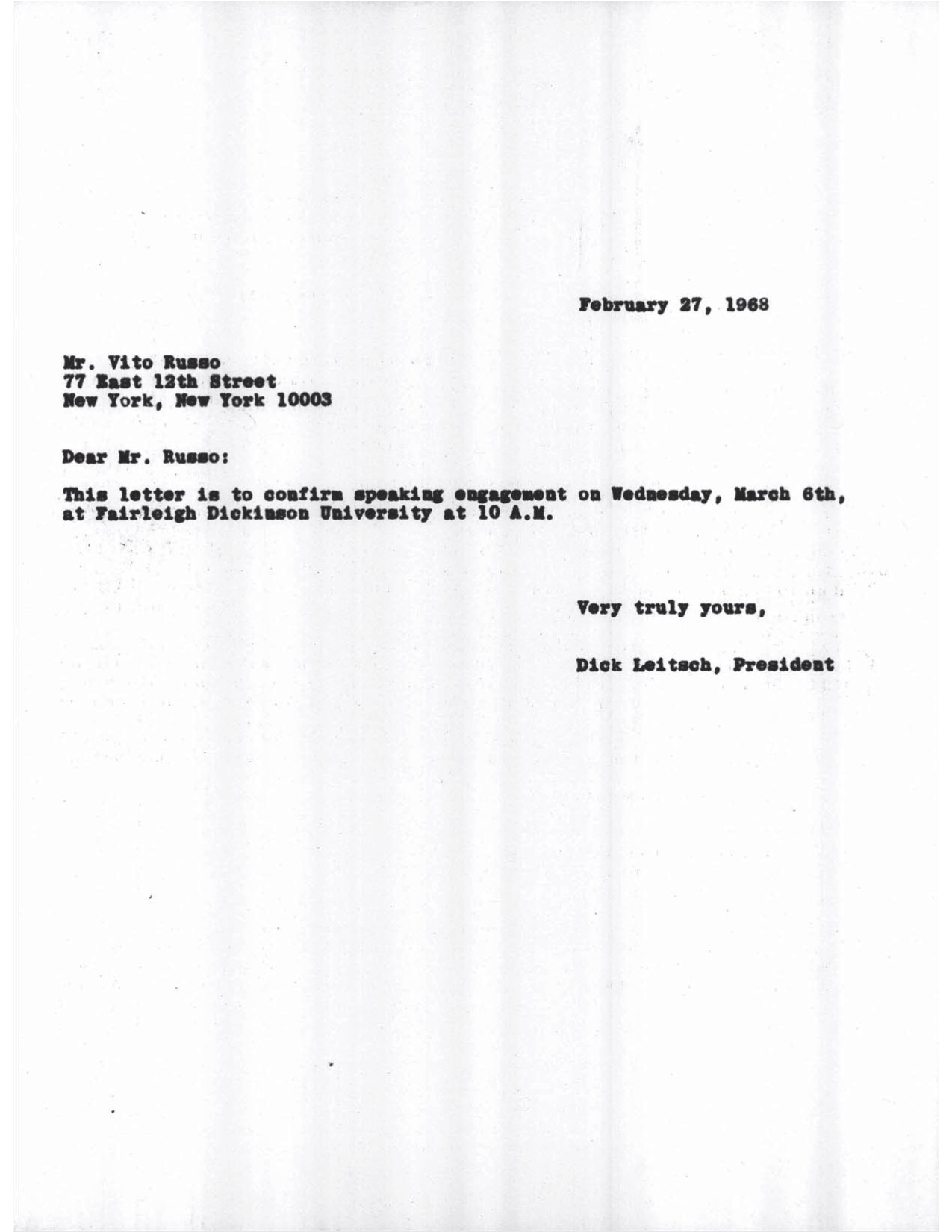

But Vito first began challenging the status quo when he was an undergraduate at Fairleigh Dickinson University in Rutherford, New Jersey. As Vito recalls in his interview: “In 1967 or ’68, I invited Dick Leitsch, [president] of the Mattachine Society [of New York] to come speak at our school. I was on the student lecture committee. I was warned not to do that. A professor of mine—she knew that I was gay, but we never spoke about it— said to me, ‘I’m warning you, if you push this thing some day they’ll shoot you in the streets. You’re making a mistake.’ I never forgot that, but I invited him anyway. We paid him a hundred dollars and he came out and he spoke to a group of students, hostile students.”

Clearly Vito didn’t let his professor’s warning stop him then or in the years that followed when his work and his activism led him to become one of the leading and most passionate voices of the LGBT civil rights movement during the 1980s.

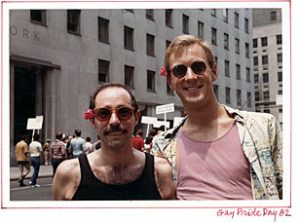

Vito died from complications of AIDS on November 7, 1990. He was 44. A month before his death, I met with Vito to choose photographs to go along with his chapter in the original 1992 edition of Making Gay History. One of the photos he chose, which you’ll find below, shows Vito with Bette Midler at the June 24, 1973 Gay Pride rally in Washington Square Park in New York City’s Greenwich Village, which followed the fourth annual Gay Pride parade. Vito was the emcee.

Here’s the story behind the photo as Vito told it to me: “The rally used to be a battleground for ideas and politics. I knew that the tensions would be running high that day because a group of radical lesbians were opposed to a couple of comic drags scheduled to be a part of the entertainment program. Drag was high on their hit list. So I began working on Bette Midler weeks in advance to come and sing to sort of calm things down. Well, the lesbians heckled the drag queens throughout their numbers, and when it was over, Jean O’Leary [the founder of Lesbian Feminist Liberation] got up and made a very angry speech in which she said that men who impersonate women for profit insult women. All hell broke loose in the audience between the men and the women, and Bette got up on stage and sang ‘Friends.’ She had brought Barry Manilow with her. Bette worked like a charm. It wasn’t that the issues were forgotten, but she provided a tremendously healing presence. It was a great thing for Bette, too. She said later that it was one of the great things she did, that she felt like she was Marilyn Monroe singing in Korea.”

To learn more about Vito and his work, and for other information related to the episode, have a look at the resources below.

———

Michael D. Klemm from CinemaQueer.com provides an overview of Vito Russo’s life in this article.

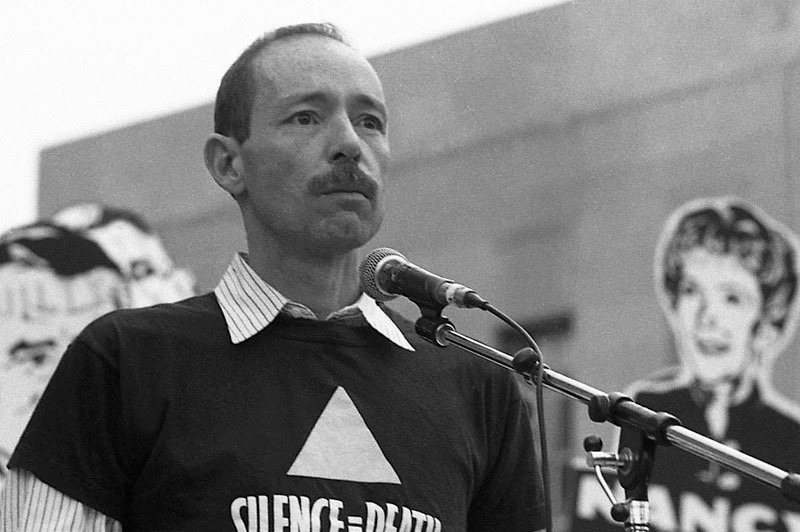

Learn more about Vito’s landmark book, The Celluloid Closet, here.

In 1983, Vito produced and co-hosted 13 episodes of Our Time for WNYC public television. Have a look at the episode on AIDS.

To read a transcript of Vito Russo’s moving “Why We Fight” speech from an ACT UP demonstration in Albany, New York, on May 9, 1988, please click here. You can also watch the speech here.

Michael Schiavi’s thorough and engaging biography of Vito, Celluloid Activist: The Life and Times of Vito Russo, was published in 2011 by the University of Wisconsin Press.

Vito Russo’s oral history can be found in Eric Marcus’s book Making Gay History.

Jeffrey Schwarz directed Vito, a 2011 feature length documentary about Vito Russo. You can watch the trailer for the film here. Jeffrey also compiled hours of outtakes from the documentary on a range of topics and featuring interviews with several different people, which you can find here.

Vito Russo is also credited as a writer for the 1995 documentary The Celluloid Closet, which is based on his book and lectures.

To learn more about the depiction of male homosexuality in the silent and “pre-code” eras of film in the U.S. and Europe, have a look at Shane Brown’s video essay, Queer Romance: Gay Characters and Male Bonding in Early Film, here. The video is based on Brown’s book Queer Sexualities in Modern Film: Cinema and Male-Male Intimacy.

Vito is a featured storyteller in the Oscar-winning film Common Threads: Stories from the Quilt, in which he speaks about his late partner Jeffrey Sevcik. Here’s the trailer.

The New York Times published Vito Russo’s obituary, in which Vito was described as a film historian, critic, and advocate for gay rights.

In honor of Vito Russo’s work, GLAAD named the “Vito Russo Test” after him. The test seeks to analyze how LGBTQ characters are included within a film.

Vito Russo’s papers are archived at the New York Public Library. The collection includes correspondence, journals, photographs, extensive resources from his “Celluloid Closet” lectures, as well as various “gay and lesbian ephemera.”

In his Making Gay History interview, Vito references a 1919 film called Different from the Others, which was co-written by Magnus Hirschfeld. Have a look at this clip from the film. To learn more about Different from the Others, and efforts that have been made to preserve and restore the film, here’s a short 2012 video produced and directed by Jeffrey Schwarz.

For an overview of the AIDS epidemic from 1981 through 2011, have a look at the timeline provided in “Thirty Years of HIV/AIDS: Snapshots of An Epidemic” from amfAR, the Foundation for AIDS Research.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is the season finale Making Gay History.

Right after I signed a contract to write my book Making Gay History, I made a list. It was the late fall of 1988. AIDS was burning through a generation of gay men. Tens of thousands were dead. Thousands more were infected, many of them already sick. And that included some of the people I knew I wanted to interview. Time was not on my side.

At the top of my list was Vito Russo. He was a co-founder of ACT UP, a group committed to ending the AIDS crisis. And he was also one of the founders of GLAAD, an organization that challenged how gay people were represented in the media. Vito was also a brilliant film buff who wrote The Celluloid Closet. It was a landmark book on the history of how gay people were portrayed in film.

So I called Vito and made an appointment to interview him at his apartment in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan. Coincidentally, he lived right around the corner from the health clinic where I’d just gotten my first HIV test. I was 29, and during the three weeks it took to get the test results, I celebrated my 30th birthday.

If the results came back positive, you knew you were a dead man. Back then, the treatments were primitive. At best they’d buy you a little time. If you were negative, well, I was hoping for the best but, as usual, expecting the worst. My deal with God, and I really wasn’t a believer, but I had a deal. And the deal was to just let me live long enough to get this book done, to leave something meaningful behind. Turned out that I was one of the lucky ones—that I’d have time to tell our stories. But Vito’s time was running out.

So here’s the scene. It’s the first day of winter in 1988. We’re in Vito’s skinny home office. Film canisters and books line the exposed brick walls right up to the high ceiling. Vito is gaunt. And even if I didn’t know, I can tell he’s sick and that he’s been sick for a long time. But there’s determination in his voice—to tell his story and to live.

I clip the microphone to Vito’s pressed shirt. He lights a cigarette, draws on it deeply and exhales slowly, blowing the smoke above our heads. I hold my breath for a moment and press record.

———

Eric Marcus: Interview with Vito Russo. Wednesday, December 21, 1988. Location is Vito Russo’s home in New York City. Interviewer is Eric Marcus. Tape one, side one.

Do you remember the first time you saw a film in which gay characters were portrayed?

Vito Russo: Yeah. Advise and Consent in 1962. I was in high school. I was horrified. Don Murray had to slit his throat. He commits suicide at the end only because he’s accused of being gay. He’s not even gay. He had one homosexual experience in the Army and was being blackmailed. But now he had a wife and a kid. I remember being tremendously impressed and warned by this movie, that these kind of people kill themselves.

A few months later I saw a film called Victim, which had been released in England in 1961 and it starred Dirk Bogarde. It’s exactly the opposite, where the guy didn’t slit his throat. Instead, he tracked down the blackmailers and cooperated with the police and put them in jail, all to challenge the existing laws against homosexual behavior. Which is a tremendous thing for a movie to say in 1961.

EM: What was going on in your own life in 1961, do you recall?

VR: I was in high school.

EM: Did you know when you saw that movie that it was wrong, what they were saying was wrong?

VR: Yes. You know, that’s interesting that you would ask that question because this has always surprised me, too. I went to Catholic schools. I went to Catholic grammar school and Catholic high. With all my Catholic religious education and with all the stuff, you know, in the movies telling you it was wrong, for some reason I knew they were full of shit, that this was not wrong, and that if something so natural to who I was could be, that it had to be okay. And that I was right and that they were wrong, but that they were gonna beat me up for it so I had to keep my mouth shut.

It wasn’t like in high school I didn’t know any gay kids. There were drag queens in town who used to have parties. And we would sneak off and go to their parties. And they picked me up one night to go to the beach. We were gonna go to Seaside Heights and stay over. I must have been a junior or a senior in high school. Sixteen? Seventeen?

EM: Sixteen, seventeen, yeah.

VR: And I remember we got on the Long Island Expressway and I said, “We’re not going to Jersey.” And he said, “No, Mary, we’re going to Fire Island.” And I had never heard of Fire Island and it was like a total revelation to me that there was like this gay community out there.

EM: Do you remember anything about the movement at that time. Was there anything publicly that you knew…?

VR: The only thing I knew was I picked up magazines like ONE and I got the sense that there were people out there who were making a case for gay people, saying that they shouldn’t be persecuted. And I always thought it was sort of odd and fanciful and I never really related it to my life or my needs. But I didn’t act upon anything political in my life until after Stonewall.

EM: Do you recall Stonewall? Do you recall reading about it?

VR: I was there, but I wasn’t inside. I was outside. By the time I got there it was basically over. I went across the street to the park. There’s that little triangular park, and I sat in a tree.

EM: You were primarily an observer?

VR: Yes. I had no connection or knowledge that there was, in fact, the beginnings of an activist movement going on right around that issue. It wasn’t until maybe a few months later. Maybe it was just July. And there was a bar on 10th Street in a basement called the Snake Pit. They raided the Snake Pit.

Among the customers arrested was an Argentinean national. And Diego Vinales was here on a visa. And he was afraid that if it came out that he was gay he would be deported. And he jumped from the second floor of the police station window on 10th Street to try to escape and landed on a spike fence. And they had to bring acetylene torches to cut him off and he was brought to St. Vincent’s Hospital in critical condition, at the edge of death for like three days. He eventually lived, by the way, and went back to Argentina.

I was on my way home from work and I passed St. Vincent’s. There was a candlelight vigil and I remember being handed a leaflet. And the leaflet said, “No matter how you look at it, Diego Vinales was pushed.” And that’s when I put two and two together, when I realized the political impact of a social event. That in fact he was pushed from that window. He was pushed by society. That if he didn’t have to be so scared of being deported, he wouldn’t have jumped. And so for the first time the organized response reached me on a gut level. And that was the following Thursday when I went to my first Gay Activists Alliance meeting.

EM: So then you were involved in activist activities through the early ’70s.

VR: What was happening by 1971, ’72, ’73 was that I was in graduate school in cinema, getting a masters in film. At the same time I was working days at the film department at the Museum of Modern Art. And I was heavily involved with the Gay Activists Alliance. So those three facts sort of conspired to make me realize that I wanted to write a readable, accessible book about the history of the ways in which lesbians and gay men had been portrayed on the screen, especially in mainstream movies, which reach most people, because I felt that our image was at the root of homophobia. That people were being taught things about us as gay people that simply weren’t true. And they were being taught this by the mass media, by movies, by whatever. And that if I could address that, that that would be what I could do to help.

EM: What was the reaction when the book was published?

VR: I heard comments from people in Hollywood who said, “You know, this is a very important book because what you’ve done here is you’ve illuminated the ways in which we have not dealt with this subject or dealt with it,” whatever. And I wonder often, I mean, I have no way of perceiving whether or not the book did any good in terms of its actual impact on movies because I still see most mainstream Hollywood films as virulently homophobic.

History has brought us to a point where AIDS suddenly intervened and AIDS has thrown a monkey wrench into any progress that Hollywood was making in the ’70s. And now people are just “A,” scared to deal with this subject at all, or “B,” homophobic in the extreme. You just can’t go to a movie in which they don’t slip in some fag joke.

I mean, a great film could be made about the tragedy, and the drama, and the courage of this community in the face of a fatal disease. In my life I’ve never seen such courage, the way people are bearing up, losing their friends. There’s a story there. There’s a movie there.

EM: There are many movies.

VR: There are many movies there. They don’t want to make them, you know, because it’s yet not happening to the real people, the general public, the heterosexuals.

EM: When did you become aware of the issue of AIDS? And then I’d like to talk about you personally. It’s affected you quite dramatically.

VR: Yeah.

EM: If I steer into territory that you don’t want to talk about, tell me.

VR: No, there’s no problem with this.

In retrospect, now that we all look back on it, because of probably geography and politics, I was, and my friends, probably knew about AIDS before most people in the country because of where we are placed. There were a group of people who knew each other from Fire Island. I had met a guy named Nick Rock. We played cards occasionally and, like myself, was a collector of films.

Nick was probably the first person I knew who died of AIDS, but we didn’t know that that’s what the disease was at the time. It was only 1979. We were told that Nick died of cat scratch fever, which does not kill you. You know, it was just not possible. But the fact of the matter was that he had no immune system, so he did die of cat scratch fever.

It was about ’82 or ’83 when I really… The bulk of the bad news came to us. And then my boyfriend got sick. And that was sort of the beginning of an even more intimate involvement for me because…

EM: That was ’84.

VR: It was ’84, ’85, I guess. Jeffrey got sick and wanted very much to be in San Francisco. Jeffrey, uh, Jeffrey grew up in Pittsburgh, went to San Francisco State and loved San Francisco and didn’t want to leave there. And our relationship, we lived together for five years, we moved back and forth.

When Jeffrey got sick, he wanted to choose to be sick in San Francisco. And so I got a job at the San Francisco AIDS Foundation. And I lived in San Francisco with Jeff. Jeffery was sick for a long time. A year and a half. I didn’t know what to do to save him. You know, when you love somebody you always feel like they’re not gonna die as long as you’re with them, you know?

EM: It’s true.

VR: I mean, if you stay with them and you take care of them, that they won’t die. And I really felt like, you know, against all rational truth, I could save him.

Jeffrey became, at the end, very unmanageable emotionally and psychologically. He was very difficult to live with. And I was sick myself. And so it became a constant battle of how much stress I could put myself under taking care of him.

EM: Because you were ill.

VR: Because I was ill. And eventually I had to go to Australia. I was booked to do a lecture at a gay film festival. I was on my way home. They couldn’t reach me. I was en route from Melbourne to Honolulu. They didn’t know where to reach me. He was dying. He was in San Francisco General. And I couldn’t get a flight out of Honolulu for 24 hours. There was no space. And when I arrived in San Francisco, he had died the night before. The last time I saw Jeff, he was in a drawer at the morgue and they opened it up and they showed me him and I spent a few minutes with him and I held his hand and said goodbye to him.

You know, I was devastated by the fact, “A,” that I wasn’t with him, you know, and couldn’t reach him, and didn’t see him before he died. And also, and I miss him terribly. I mean, just terribly. He’s been gone almost three years now and I’m still sick and I’m very lonely. You know, it’s hard to live alone and be sick alone. And as many of your friends as you have—and I have good loving friends and a great support system—people cannot be sick for you and they can’t suffer for you and they can’t be with you all the time.

EM: Jeff had you during the time he was ill. And he did have someone full-time.

VR: Yeah. I took him to the hospital and I took him to the doctor and I fed him and I cooked. I mean, I did what I wanted to do, but then Jeffrey was gone and I was alone.

EM: And then you get in the cab by yourself…

VR: And there was nobody to take care of me. Who the hell is going to get into a relationship with somebody who is probably gonna die soon? You know, they don’t want to put themselves through that. Most of the people who were my friends are dead. Most of my friends are dead. And at this age that shouldn’t be.

EM: You’re only 42.

VR: Yeah, it’s not natural, by any definition of the word natural. It’s not natural at this age for me to have lost most of the people I love.

And so you throw yourself into politics.

EM: The images I’ve seen of you in the last couple of years—well, I’ve seen you on television. I’ve seen you in a very, very activist role.

VR: Yes.

EM: So, has it been AIDS then that propelled you?

VR: Yeah, it has. I was one of the people, who along with Larry Kramer and Vivian Shapiro and Tim Sweeney and a couple of other people, who founded ACT UP, which became a whole new phase of activism, not only for me, but for the community in general. And it’s a new kind of activism, because it’s created a coalition, which we were never able to achieve in the ’70s.

ACT UP is composed of gay people and straight people, women and men, Black and white. You know, and effectively. ACT UP has been a very interesting experience because all these people have one thing in common and that’s they want to put an end to the AIDS crisis by any means possible.

EM: How do you see your role in ACT UP in the future?

VR: It’s difficult to say because at this point my priority is my survival and my health. And very often I have to take long hiatuses from ACT UP because it’s emotionally and physically exhausting for a person with AIDS to go out there in the streets at 7 a.m. in the freezing cold and block traffic. It’s really just, you get sick from it.

I feel like my function and my role right now is, “A,” to survive physically, to survive this disease, to be one of the people who survives this disease. I would like that very much obviously. Nobody wants to die. But also I want to be around to kick their asses after it’s over. To say I lived through it, you know? To be alive to witness what happened. To tell the world what happened so that people will realize what we all went through. Because I think our lives have been devalued. These are brave, courageous, beautiful people who are dying.

EM: Vito, is there anything I haven’t asked you that you’d like to comment on, any event, thought, place, time, people?

VR: I find it interesting from what I know about the history of the gay movement, that there always have been and there will always be people who are willing to put their lives on the line for these ideas. Starting from Germany in the turn of the century, in 1895, and then into the early teens and twenties, there were a group of people in Germany, headed by Magnus Hirschfeld, who were willing to put their lives on the line. They were willing to make a movie called Different from the Others, which the Nazis seized and burned. Then in the 1940s and the 1950s there were the Harry Hays and the Barbara Gittings and the Mattachine Society and then in the ’60s, gay liberation. It’s the more radical issues that I think are still gonna be fought over, whether gay people have the right to adopt children…

EM: Get married.

VR: Get married, teach in the public schools, which they do now, you know, but be open about it. And those battles are battles that are gonna be fought long after you and I are gone. But you have to make a contribution while you’re here. I mean, that’s been my whole life is, to leave my book behind. That I know after I’m dead that book is gonna be on a shelf someplace. And what I have to say will reach people. And the things I’ve written.

You know, because, it’s like, who was the person who said that? Pedro Almodóvar. He said, the thing is, is you can’t regret your life, otherwise why did you live? What was the point of having a life if you didn’t say something or do something that was gonna survive after you’re gone? And that’s the way I feel about it. I mean, I really feel the reason why I’m here is so that I could leave this book and these articles so that some 16-year-old kid who’s gonna be a gay activist in the next 10 or 15 years is gonna read them and carry the ball from there. And that’ll happen. Happened with me. Harry Hay passed the ball to the Mattachine and they passed the ball to us.

EM: And you’ll pass it on.

———

EM Narration: Back in 1981, I had been one of those young people who found Vito’s book on a shelf. I was a year out of college and working as a temp at Harper & Row. They’d just published The Celluloid Closet. It had a silvery jacket and a subtitle that caught my eye: Homosexuality in the Movies. I wasn’t in the closet back then, but I wasn’t exactly out either. So I waited until lunch hour when no one was around and I picked up the book.

I couldn’t put it down. Vito opened my eyes. I had no idea how much the movies had shaped how I thought of myself and how the rest of the world thought of people like me. It was insidious. And really infuriating.

Seven years later Rick Kot, a young gay editor at Harper & Row, commissioned me to write Making Gay History. I wonder now how much Vito’s work influenced my own. One thing’s for sure, he inspired me to ask a lot of questions.

I saw Vito twice after that first interview. The last time was a month before he died. I went by his apartment to go over photos with him for his chapter of the book, including my favorite, a photo of Vito and Bette Midler from the Gay Pride rally in 1973. You can see that photo and read the story behind it at makinggayhistory.com.

Vito Russo died on November 7, 1990. He was 44 years old. He outlived his boyfriend, Jeffrey Sevick, by four years.

———

So, this episode marks the end of season one of Making Gay History. Thanks for listening and thank you for your tweets and emails. Thanks to the support of the Ford Foundation, I’m thrilled to tell you that we’ll be back with a second season of Making Gay History.

In the meantime, I want my crew to know how grateful I am for their commitment, enthusiasm, and dedication to bringing Making Gay History to life. Thank you to executive producer, Sara Burningham, who has gone above and beyond to produce such beautiful pieces. Thank you to our social media guru, Hannah Moch; our webmaster, Jonathan Dozier-Ezell; and our researcher, Zachary Seltzer. We had production help from Jenna Weiss-Berman, who inspired us to reach high and has helped us every step of the way. Our theme music was composed by the very talented Fritz Myers.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and ONE Archives Foundation.

Funding is provided by the Arcus Foundation. Learn more about Arcus and its partners at arcusfoundation.org.

And if you like what you’ve heard, please subscribe to Making Gay History on iTunes, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts. You can also listen to all our episodes at makinggayhistory.com.

So long. Until next time.

###