“Dear Abby”

Pauline Phillips, founder of the “Dear Abby” column, in the mid-1960s.

Pauline Phillips, founder of the “Dear Abby” column, in the mid-1960s.Episode Notes

From Eric Marcus: To understand how a heterosexual, Jewish, Midwestern daughter of a Russian immigrant singlehandedly influenced how Americans thought about gay people, how parents saw their gay kids, and how gay people felt about themselves, you have to go back in time. Before Google and social media. Before the internet. Before cable TV. Back to a time when everyone read a newspaper and twin sisters born on the 4th of July in 1918 wrote competing syndicated advice columns read by tens of millions of people around the world. Pauline Esther Friedman Phillips wrote the “Dear Abby” column under the pen name Abigail Van Buren. Her twin sister, Esther Pauline Friedman Lederer, wrote the “Ann Landers” column.

Pauline Phillips (nicknamed “Popo” by her family) affirmatively took on the issue of homosexuality and the rights of gay people in her column—beginning in the late 1960s/early 1970s—at a time when doing so risked backlash from her readers and the newspapers in which her column appeared. She was one of the only high-profile celebrities to do so during an era when gay people were still considered sick, sinful, and criminal. But despite the bags of hate mail she received from those who disagreed with her, she never flinched or backed down, which is why she holds a special place in the hearts of gay people (and their family members) who grew up with her column. Phillips’s admonition to the parents of a gay child that they should “love him, love him, love him,” rings as true today as it did when she first wrote those words in her column decades ago.

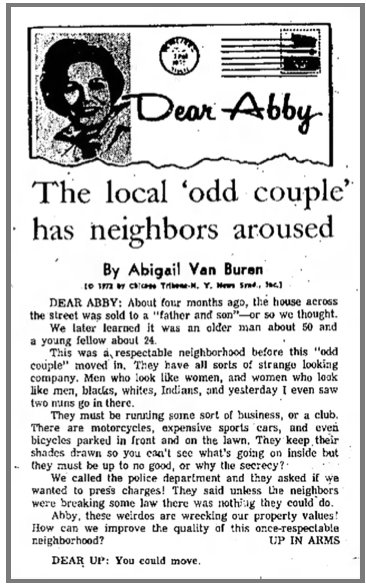

One of the columns Phillips references in her Making Gay History interview concerns people who were upset about new neighbors, a column that she said gay people loved. Here’s a facsimile of the actual May 3, 1972, letter reproduced in its entirety along with Phillips’s three-word response (just in case you have a hard time reading the facsimile, we’ve provided a typed version as well).

DEAR ABBY: About four months ago, the house across the street was sold to a “father and son” — or so we thought. We later learned it was an older man about 50 and a young fellow about 24.

This was a respectable neighborhood before this “odd couple” moved in. They have all sorts of strange-looking company. Men who look like women, women who look like men, blacks, whites, Indians. Yesterday I even saw two nuns go in there!

They must be running some sort of business, or a club. There are motorcycles, expensive sports cars and even bicycles parked in front and on the lawn. They keep their shades drawn so you can’t see what’s going on inside but they must be up to no good, or why the secrecy?

We called the police department and they asked if we wanted to press charges! They said unless the neighbors were breaking some law there was nothing they could do.

Abby, these weirdos are wrecking our property values! How can we improve the quality of this once-respectable neighborhood? — UP IN ARMS

DEAR UP: You could move.

Pauline Phillips’s daughter, Jeanne Phillips, began working with her mother as a teenager answering mail from other teenagers in order to earn her allowance. When her mother began experiencing the onset of Alzheimer’s disease in the mid-1980s, Jeanne began writing the column. Jeanne was acknowledged publicly as the co-creator of “Dear Abby” in 2000, and Pauline officially retired in 2002. Like her mother, Jeanne has been an unwavering and compassionate supporter of LGBTQ people and full equal rights, having come out publicly for marriage equality in 2007. That same year Jeanne was awarded the first ever “Straight for Equality” award from PFLAG (then known as Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays). Jeanne’s mother first recommended PFLAG to the distraught parent of a gay child in a “Dear Abby” column in 1984.

To learn more about Pauline Phillips and the “Dear Abby” column, have a look at the resources below.

———

To get a better sense of Pauline Phillips and what she was like in person, have a look at this episode of Larry King Live from January 8, 1990.

Archives of the “Dear Abby” column are available from 1991 to the present on this website.

The “Dear Abby” column is credited by PFLAG as helping them to gain national attention in the 1980s. For more on PFLAG, you can listen to our episode with PFLAG founders Jeanne and Morty Manford here.

The Daily Beast collected some of Pauline Phillips’s most quippish “Dear Abby” responses.

The New York Times published Pauline Phillips’s obituary in January 2013. It contains some fascinating stories, more of her “flinty” replies, and a brief summary of her life.

Pauline Phillips’s oral history can be found in Eric Marcus’s book Making Gay History.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

In my first round of interviews for my book, I only spoke to one person who was a household name: Dear Abby. She was also known as Abigail Van Buren. Her given name was Pauline Esther. Her nickname was Popo. And my grandma was just one of 110 million people, every day around the world, who read what Dear Abby had to say.

When I was a kid, my mom sent me to Ziggy’s, the corner candy store, to get the Sunday newspapers. They were really heavy. My favorite part of the paper was the comics. My immigrant grandmother went right to Dear Abby’s column where she could get the latest advice on everything from marriage and children to abortion and homosexuality.

Abby never minced words. Biting humor was her weapon of choice. But whatever the topic, her warmth and compassion and her common-sense wisdom came through loud and clear.

Abby began writing her column in 1956. From the start she got letters asking for advice on homosexuality—from gay people who wanted to change to parents who wanted to know what they did wrong. Abby did something no other famous public person did. She said positive things about gay men and women and homosexuality in general. That earned her bags of hate mail and a place in the hearts of gay people everywhere. Dear Abby is my personal hero.

So, not surprisingly, I’m a bit starstruck as I pull into Abby’s driveway in Beverly Hills and then walk up to the front door of her French Provincial mini-mansion. I ring the bell. Abby opens her double-height front door and greets me with a welcoming smile. She is tiny, maybe five feet tall. She’s dressed in lavender hostess pajamas and pink fluffy slippers. Her hair is perfectly coiffed. Her complexion is flawless.

We take seats at the bar in Abby’s living room. A selection of her old newspaper columns cover the marble counter. My hands shake a bit. Thankfully, I remember to press record.

———

Abigail Van Buren aka Dear Abby: Well, I want to get all that stuff out of storage and I want that stuff in my office where I can put my hands on it. I don’t care if it’s 1956. Okay? Thanks, honey. Carry on, babe. Bye.

That’s Jimmy. What a trip. He used to be a Catholic priest. He’s now in my office and he’s fabulous. Jimmy Hughes. He’s a darling.

Eric Marcus: May I attach this to you? I don’t want to, uh…

AVB: Sure.

EM: Do you prefer to be called Mrs. Van Buren, Abby…?

AVB: Abby, Abby, Abby.

EM: Abby, okay. When you first started writing your column in 1956, did you get letters concerning the issue of homosexuality or lesbianism?

AVB: Yah, I did. “How can I change? What can I do to change?”

EM: Even in 1956 you got that kind of mail?

AVB: Oh, yah. This is an early one. “Dear Abby: To get right to the point, I’m gay. But I don’t like being gay. I want a wife, children, and a normal social life. I also have a career I enjoy greatly, in banking, in which further advancement is impossible if it becomes known that I’m gay. Psychiatrists and other therapists I’ve gone to have tried to help me adjust to my homosexuality rather than help me to change. Abby, adjusting to being homosexual is fine for those who have accepted their homosexuality, but I haven’t. I know I’d be happier straight. Please help me.”

He signs, “Unhappy in Houston.” I say, “Dear Unhappy: Did you choose to be homosexual? If so, then you could choose to be straight. But if you have always had erotic feelings for men instead of women, then face it, you are homosexual and even though you may be able to change your behavior, you will not be able to change your feelings. Some therapists insist that if a homosexual is sufficiently motivated, he or she can become straight. Maybe so, but the chances are slim. Marrying and having children may make you happier, but what about the other people you involve? To thine own self be true. Only then will you find true happiness.”

Did you ever hear of Franz Alexander?

EM: No, I haven’t.

AVB: Franz Alexander was called the father of psychosomatic medicine. He was born in Budapest. And he was the head of the Chicago Institute for Psychoanalysis. He died in ’64. He was a very charming, wonderful guy. A very good friend of my husband’s and mine. He said regarding homosexuality of course there is no cure because it’s not a disease.

EM: Alexander said this.

AVB: Yah. He said, there is no cure. This is where I got my notions originally.

EM: How far back does that date?

AVB: Maybe 1945, 1946, something around that time. But he gave me a lot of my ideas. He really educated me.

EM: That was a rather radical way of thinking in those days.

AVB: It certainly was. It was dangerous in some circles.

EM: Why was it dangerous?

AVB: It took courage to come out and say, “What do you mean sick? This is natural for them. This is the way they go naturally.” Now I’ve known a lot of gay people. And you can change one’s behavior, but you can’t change your feelings. And all these crazy stories that you hear about how they got that way. I’ve always thought people were born that way.

EM: You must have known people who were gay at that time then, personally.

AVB: Yah, well, my hairdresser. He’s like a brother. And he’s been my hairdresser for about, maybe 29 years. He came from Louisville, Nebraska. Beautiful guy and just a sweetheart. And he had to leave the little town of Louisville because, well, he just couldn’t survive there. I’ve taken him to Korea with me when I was a Miss Universe pageant judge. We just had a ball. He and I are in a helicopter. Have you ever been in a helicopter?

EM: Thank god, no.

AVB: Okay. And Cloyd is his name of all things.

EM: Cloyd?

AVB: Cloyd, but he’s not really nellie. But he’s not all that subtle. So we’re in this helicopter—these are all big Army guys, you know. And we go up and then back and his purse slid back. That’s why I said to the, “Hey, hold it,” I said, “My friend lost his purse.” The guys broke up in the front. The guy that was driving the helicopter just cracked up.

EM: Knowing someone like that from that part of the country, I would think it would have given you some insight into what it was like for young kids growing up in small towns who were gay. Did you ever talk about…?

AVB: Oh, yeah. Oh certainly, certainly. Never came out to his parents. He said they couldn’t handle that. His mother just adored him and he was a wonderful son, just a wonderful son.

EM: You were probably the only voice out there at that time. And I would imagine you received lots of letters from homosexuals, men and women, with questions.

AVB: And parents of gay people, too. Because to them it was, “Where have we gone wrong?” I’d tell them, “You didn’t go wrong. Just love him, love him, love him.” That’s it.

EM: How did your paper let you get away with it?

AVB: Lots of papers complained, but they never dropped me. The San Diego Union had never published the word homosexual in their newspaper when I started. I was a breakthrough. And they’re still pretty conservative, but that was the first time they’d ever published the word “homosexual,” unless they dragged a guy, this guy was going to jail or something, but in a column? And to be kindly toward a homosexual? To be understanding?

EM: It seems things really heated up in the early ’70s for you. There’s a column I came across in which you write rather strongly. In 1971, you wrote, “To those who wrote to blast me for my refusal to put down the homosexual: The most burdensome problem the homosexual must bear is the stigma placed upon him by an unenlightened and intolerant society. Their sexual bent is as natural and normal for them as ours is for us.” And then you talk about they, too, are God’s children. It seems that—my impression was that things began to heat up in that issue, the homosexuality issue, in the late ’60s, early ’70s. That’s when gay civil rights came into bloom. Did you come under more attacks during that time for your comments or did you get a steady stream of hate mail?

AVB: It was a steady stream of hate mail. Every time I’d run something compassionate or sympathetic I would get a lot of, I’d get hate mail. It wouldn’t bother me, but I got a lot of it, but I have made that statement, “God made gays as well as he made straights.” I’ve said that because that’s the way I feel.

I think I’ve always been bold. I never fudged. I never apologized. And I got a lot of… My lord, I tell you, the Bible thumpers really let me have it. I was getting Leviticus, and Corinthians, and Proverbs and I was getting all that stuff. You’re not going to change their minds because they’re fanatics. They can’t help it because this is what they believe. Fine. That’s okay with me. But don’t tell me what to believe. Biblical injunctions mean nothing to me, because you can find all kinds of contradictions in the Bible. You can find anything you want in the Bible. If it makes people behave better, fine. But if it makes people less understanding of their fellow man, then something is wrong, you see. Your beliefs should make you better and should make you kinder, not more hateful.

EM: How did you handle the negative mail? Wasn’t it upsetting to you in some way?

AVB: Well, I guess it was upsetting. But it saddened me that people could be so unfeeling. Ignorant.

EM: What sorts of things did they say to you? Do you recall?

AVB: I ought to burn in hell, you know. Oh, yes.

EM: Really.

AVB: Oh, sure. The fundamentalist types would say that. “You should be saved.” People want to show me the light. They think I’m misguided. They say, “You’re a good Christian woman.” I always write back and say, “Thank you, you’re very kind, but I hope I’m a good Jewish person, because I am Jewish.” I always let them know that.

EM: There was a column that you wrote—this is the woman who complained about the new neighbors next door. A strange man, the couple.

AVB: Well, the letter was, “This is a nice neighborhood and we’re very disgusted with these types, and what could we do to improve the neighborhood?” And my answer was, “You could move.” The gays thought it was hilarious. But other than just being amusing, entertaining, there was a good message there.

EM: Which was?

AVB: Which was that they have a right to be there. If you don’t like it, you could move because they have as much right to be them as you have to be yourself.

EM: How much of an impact do you think you’ve had as one person on this issue?

AVB: I think I was the, well, I wouldn’t say the first. I was one of the first persons on the national level that wasn’t gay, I wasn’t defending myself. I was defending everyone’s right to be themselves, gay, straight, no matter.

EM: And that was beginning in the 1960s.

AVB: People tell me it took a lot of guts, but I was happy to have a platform, such as I had.

EM: Were you at all concerned that your views on this subject would harm your career, because at the time you wrote, the 1950s, 1960s, even to the ’70s…

AVB: I had an awful lot of people who thought I was wrong, why should I stick my neck out for them, you know. That didn’t bother me. I never lost a paper that I know of because of this.

EM: Where does the courage come from?

AVB: I don’t know. Eric, I can’t tell you. But it must have been there. It was there all the time. I got love letters as well as hate letters. That keeps me going.

EM: Those are the ones you read.

AVB: I read ’em all.

EM: Thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure talking about this.

AVB: Eric, a pleasure and I wish you much success with your book. I know it’s going to be good. You ask good questions.

EM: Thank you.

———

EM Narration: Soon after I interviewed Abby, she introduced me to her daughter, Jeanne. We became fast friends. Jeanne took over the “Dear Abby” column from her mom in 2002 and, like her mom, she’s been a fierce ally to gay people and a champion of LGBT rights.

Jeanne’s mother died on January 16, 2013. She was 94. If you’ve never seen a picture of Abigail Van Buren, Jeanne’s mom, have a look at the iconic photo from the mid-1960s I’ve posted at makinggayhistory.com. I don’t know about you, but when I look at that photo I can’t imagine not taking her advice.

———

I’ve got a few key people to thank for making this podcast possible. Thank you to our executive producer, the hard-working Sara Burningham; our audio engineer, Casey Holford; and our composer, Fritz Myers.

Thank you also to our social media guru, Hannah Moch; our webmaster, Jonathan Dozier-Ezell; and Zachary Seltzer, the man responsible for each episode’s show notes. We had production help from Jenna Weiss-Berman, who believed in this podcast even before it was a podcast.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division.

Funding is provided by the Arcus Foundation, which is dedicated to the idea that people can live in harmony with one another and the natural world. Learn more about Arcus and its partners at arcusfoundation.org.

And if you like what you’ve heard, please subscribe to Making Gay History on iTunes, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts. You can also listen to all our episodes on makinggayhistory.com. That’s where you’ll find photos and information about each of our interview subjects.

So long. Until next time.

###