Dismantling a Diagnosis — Episode Two: The Cure

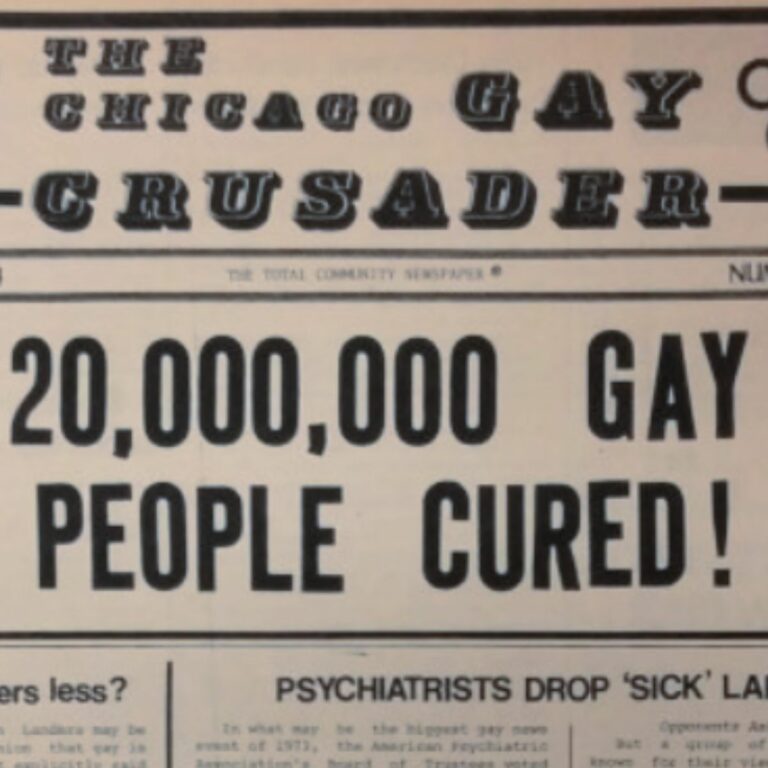

Headline on the front page of the January 1974 issue of the Chicago Gay Crusader announcing the American Psychiatric Association’s removal of homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Headline on the front page of the January 1974 issue of the Chicago Gay Crusader announcing the American Psychiatric Association’s removal of homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.Episode Notes

A half-century ago, millions of homosexuals were cured with the stroke of a pen when the American Psychiatric Association decided to change its diagnostic manual and remove homosexuality from the list of mental disorders.

In this episode, we journey through several milestones in the battle for gay liberation and acceptance as we focus on how the field of psychiatry defined, and distorted, what it meant to be homosexual. Homosexuality was officially classified as a mental disorder in the 1952 edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, but the narrative that equated being gay with being mentally ill had been emerging for decades. The nascent gay rights movement in the 1950s was caught between believing the sickness narrative and seeking treatment, and questioning the diagnosis and using their own voices to fight back. A groundbreaking 1956 study by psychologist Dr. Evelyn Hooker debunked the notion that gay men were, by default, mentally ill, and even though societal pressures dissuaded Dr. Hooker from extending her study to lesbians, her research gave activists a foundation to advance the discourse. The years that followed brought continued campaigning by gay activists, and with the help of enlightened psychiatrists who became allies and closeted gay psychiatrists who had the courage to speak out, 1973 brought victory. The APA overturned its classification, effectively “curing” millions of homosexuals overnight.

Episode first published December 22, 2023.

———

Learn more about some of the topics and people discussed in the episode by exploring the links below.

General resources about the activism that led to the APA’s 1973 resolution to declassify homosexuality as a mental disorder:

- The award-winning 2020 documentary Cured; Q & A with the filmmakers Patrick Sammon and Bennett Singer (PBS).

- American Psychiatry and Homosexuality: An Oral History (eds. Jack Drescher and Joseph P. Merlino, Routledge, 2007).

- “81 Words,” a 2002 This American Life episode from reporter Alix Spiegel, whose grandfather was president-elect of the APA at the time of the change.

Don Lucas:

- Biography and overview of Lucas’s papers housed at the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco.

- 2003 obituary (SFGATE).

Dr. Alfred Kinsey:

- Biographical overview (Kinsey Institute).

- The Kinsey Reports, both accessible via the Internet Archive: Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (1948); Sexual Behavior in the Human Female (1953).

Lavender Scare:

- “‘These People Are Frightened to Death’: Congressional Investigations and the Lavender Scare” by Judith Adkins (Prologue Magazine, Summer 2016, Vol. 48, No. 2).

- The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government by David K. Johnson (2004, 2023, University of Chicago Press).

- The Lavender Scare, a 2017 documentary by Josh Howard.

Dr. Evelyn Hooker:

- MGH episode featuring Dr. Hooker, with accompanying resources.

- Broad biographical overview and tributes (lgbpsychology.org).

- Changing Our Minds: The Story of Dr. Evelyn Hooker, a 1991 documentary by Richard Schmiechen.

- Summary of Dr. Hooker’s study “The Adjustment of the Male Overt Homosexual” (American Psychological Association).

Dr. Judd Marmor:

- Oral history in the original edition of Eric Marcus’s Making Gay History book (HarperCollins, 1992).

- 2003 obituary (New York Times).

Dr. John Fryer aka Dr. Henry Anonymous:

- “Honoring the 50th Anniversary of a Speech That Changed LGBTQ+ History” by Patrick Sammon and Bennett Singer (The Advocate, May 2, 2022).

- Digital copy of Dr. Fryer’s nine-page handwritten 1972 APA speech (Historical Society of Pennsylvania).

- 2003 obituary (New York Times).

Ron Gold:

- Overview of Gold’s papers housed at New York City’s LGBT Community Center.

- Archival radio programs featuring or hosted by Gold (Pacifica Radio Archives).

- 2017 obituary (Gay City News).

Other MGH episodes about some of the people featured in this episode, with accompanying episode notes:

- Barbara Gittings and Kay Lahusen: part 1 and part 2

- Hal Call

- Frank Kameny

- Billye Talmadge

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: On December 15, 1973, the board of trustees of the American Psychiatric Association (also known as the APA) approved a resolution striking homosexuality from the list of mental disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. It was, in the words of the newly founded National Gay Task Force, “the greatest gay victory.” And it felt to many like it had happened fast—as though this psychiatric orthodoxy had just been swept away in the tidal wave of post-Stonewall gay liberation activism. But to understand how the sickness label—a label that had been used to persecute so many—was overturned so seemingly easily, we’re turning back the clock, to before Stonewall, to the decade before, to the 1950s.

———

Barbara Gittings: We were cured overnight by a stroke of the pen. Just as, originally, we’d been made sick by probably a stroke of the pen.

———

EM Narration: This is Making Gay History. I’m Eric Marcus. Welcome back to our special miniseries marking 50 years since we gay folks were cured “with the stroke of a pen,” when the APA acknowledged that being gay was not in fact itself a mental illness.

This is episode two: The Cure. Act one: Secret Societies, and Dr. Alfred Kinsey.

———

Host: Yes. Who’s speaking, please?

Caller: Well, I’d rather remain anonymous.

Host: Alright.

Caller: I’d like to address my question to Mr. Call, was it?

HC: Yes.

Caller: Um, is there a place that a homosexual can seek aid…

———

EM Narration: The audio is hard to make out, but an anonymous caller is asking, “Is there a place or an organization that a homosexual can seek aid from?”

———

Hal Call: Yes, there are several organizations in the United States today—the Mattachine Society, of which I’m a representative; the Daughters of Bilitis; ONE, Incorporated, of Los Angeles; a group called the League for Civil Education in San Francisco. All of these organizations will refer individuals in trouble or in conflict with the law to competent attorneys. And they will refer individuals in various other kinds of trouble: religious, psychiatric—situations which indicate, uh, professional counseling or therapy is necessary. And many other types of aid to individuals who call upon them. They are not advocating or upholding the idea of homosexuality. They are simply recognizing that it does exist in nature and always has been with us, and that laws and attitudes to the contrary have actually not reduced the incidence of it one bit. We’ve spent a lot of effort trying to do that, but it doesn’t seem to have worked.

———

EM Narration: That scratchy old tape is from a panel discussion at the fourth annual convention of the early gay rights group the Mattachine Society in 1957 in Denver. I’m pretty sure that’s Hal Call speaking; you’re going to get the chance to meet him a little later in the show. And as he just told that worried anonymous caller, the early gay groups focused on mutual aid, challenging police entrapment, and education. They also held anonymous discussion groups so people could, perhaps for the first time in their lives, talk to other gay people about what it meant to be gay.

That tape is from a trove of recordings from the 1950s that Donald Lucas, a member of Mattachine, had held onto for decades. I interviewed Don for my book back in July of 1989. We spoke in his dusty, messy office next to the basement garage of Don’s house in San Francisco. He’d had a serious heart attack and the medication he was taking had jumbled his memories, so I wasn’t able to include him in my book. But as we talked, piled all around us in his office and even on top of his aging car in the garage, were scores of boxes full of papers, files, and…

———

Don Lucas: You see the tape tapes up there?

EM: Yes. Yes.

DL: Those are all just dozens and dozens of, um, conversations.

———

EM Narration: Don Lucas had recorded all the Mattachine conventions and hours and hours of panel discussions and Mattachine Society meetings. Among the recordings are Mattachine panels featuring psychiatrists describing gay people as “arrested in their development” and “psychopathological.”

———

EM: You also invited in psychologists who considered gay people sick.

DL: Oh yes. Uh-huh.

EM: Many people cannot fathom why you did that.

DL: Because they were in the majority.

EM: Can you elaborate on that for me? And I’m not, I’m not making any judgment. I’m just curious, I’m curious why.

DL: Yeah. The, the, the majority of the, um, psychiatric world at that time considered homosexuality an illness. And, uh, so we tried to get both sides involved in, in a debate, in a dialogue, so that people could learn through this educational process. You can’t educate in a vacuum. So you have to have both sides of any question in order to come to a debate. And, um, oh, yes, we were criticized many times for doing that. I have all the tapes of all those things.

———

EM Narration: All these years later, I was so glad to discover that Don’s basement archive had survived. But I digress—archives are my love language.

You just heard Don explain how the Mattachine Society discussion groups included talks from psychologists who agreed with the official psychiatric diagnostic manual, the DSM, that homosexuality was a mental illness. Inviting those speakers is baffling now—it was baffling by the time I interviewed him at the end of the 1980s—but this was the 1950s. The movement for gay rights was in its infancy. The Mattachine was highly secretive, and that secrecy was born of fear.

Members were anonymous, many used pseudonyms. When the Mattachine Society was first founded, it had a kind of cell structure based on the example of the Communist Party. Some of Mattachine’s founders had been Communist Party members. They used that secretive structure in an effort to protect themselves, so if one branch or cell of the society was discovered or targeted by the authorities, the others could remain hidden.

The Daughters of Bilitis, also known as DOB, was the earliest lesbian group in America, founded in 1955, and it was also very careful in what it said and how it publicized its activities—as former DOB member Barbara Gittings told me when I interviewed her in 1989.

———

BG: If you said that you were, uh, uh, you know, you were providing ways for homosexuals to meet each other, uh, this could possibly put you in violation of the law for procurement in some places, and it certainly would bring down the ire of people who might find out about it and say, “This is disgusting. Here they are, you know, arranging, um, arranging to meet each other through these organizations. Let’s, uh, let’s knock them out of existence.” And they didn’t want to jeopardize their existence.

———

EM Narration: While most individual members of these early organizations were trying to remain hidden from view, by the 1950s, homosexuals, as a group, had entered the national consciousness in a big way.

Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey and a group of researchers had formed the Institute for Sex Research in Bloomington, Indiana, in 1947. In 1948 Kinsey and colleagues published Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. Sexual Behavior in the Human Female was published in 1953. It’s hard to overstate the earthquake these reports set off in American society.

That first Kinsey report found that nearly 37 percent of the adult male subjects had had at least one homosexual experience, and that 10 percent of American males surveyed were “more or less exclusively homosexual for at least three years between the ages of 16 and 55.” When Dr. Kinsey and his team wanted to gather more data for ongoing research at the institute, they sought out the early gay groups.

Here’s Billye Talmadge, who was a member of the Daughters of Bilitis at the time.

———

Billye Talmadge: We were the very first group to be, uh, interviewed by, uh, by the Kinsey Institute. We asked for that. We bou—you know, we badgered at their door to try to get some kind of, of, uh, involvement. And got it. And they interviewed us as couples, and they interviewed us as individuals.

EM: Were you interviewed for it?

BT: Oh yes. Shorty and I both were.

EM: What sorts of things did they—they must have asked everything, I assume?

Marcia Herndon or BT: Yeah, they did. You know, we put it before our membership and said, um, you know, “If you want to do this, then volunteer, but know that you’re opening the door for all kinds of questions.” And, um, we got quite a number of volunteers, quite a number of people did this. See, that took guts and, and real courage.

———

EM Narration: Hal Call joined the Mattachine Society in San Francisco in 1953. A World War II vet and a journalist, he had moved west a year earlier after he was fired from his job at the Kansas City Star for being gay. Hal was part of a push for the society to be a little less secretive.

———

HC: I was a journalist and a public relations man, and I knew that, uh—or I felt that—education and getting the word out was the best thing we could do. We had the Mattachine phone number in our telephone book here in the city of San Francisco. And, uh, the Kinsey group in Bloomington, Indiana, was soon in contact with us as soon as they found out that we had Mattachine discussion groups and a Mattachine entity going here in San Francisco.

———

EM Narration: You might expect the jolt of awareness from Kinsey’s research—that gay people were everywhere—could also spark a moment of pride and liberation. But this was the 1950s. It was a dangerous time to be gay. And the reaction to Kinsey’s research helped fuel a brutal crackdown on gay people in the form of the Lavender Scare, which paralleled the better known Red Scare.

Thanks to a 1953 executive order signed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, gay people in federal employment were investigated, exposed, and fired as a moral panic took hold of government. Homosexuals were sick and dangerous—all were seen to be potential security risks. Culturally, the backlash following the Kinsey reports reinforced the all-American heterosexual nuclear family as the only healthy, moral life to be lived.

———

EM: Was Dr. Evelyn Hooker one of the people you worked with?

HC: Oh my god, yes. I love Evelyn. Well, I’ve known her since 1953, when we had, she was present at some of those early meetings we had.

———

EM Narration: Act two: Dr. Hooker and the Men.

———

Speaker 1: May we start by asking Dr. Hooker first if there are specific questions… Or, pardon me, before we start the discussion group, I must ask one question: is there anyone present who would object to our discussion group being transcribed? Since we use no names, it’s rather hard to conceive that anyone would object, but if there is any objection…

Speaker 2: I have a question. Why should it be recorded?

Speaker 1: It’ll be recorded so that we may have a permanent record.

Dr. Evelyn Hooker: Could I add something to that? If it were recorded, I should be very grateful for your comments and, and questions about the things which I’ve said here. And since I obviously won’t be able to remember everything that’s said. But I don’t mean that as pressure, obviously.

Speaker 1: Um, then may I state that toward the end, we will turn off the recording, and if there’s anyone who wishes to ask a question off the record, then we can [inaudible]. Pardon?

Speaker 2: Can we, uh, turn the tape off?

Speaker 1: Yeah.

[Tape clicks off.]

———

EM Narration: This recording was made in 1954 with Dr. Evelyn Hooker, a trailblazing psychologist. In May of that year at the Western Psychological Association in Long Beach, California, Dr. Hooker had presented a paper titled “Inverts Are Not a Distinct Personality Type.” “Invert” was another word for homosexual back then. Dr. Hooker had come to Mattachine to share her findings. While the discussion portion of the meeting wasn’t recorded—they stopped the tape rolling to protect the anonymity of Mattachine’s members—Dr. Hooker’s presentation, a repeat performance of her Long Beach speech, was among Don Lucas’s tapes.

———

EH: I’m now reading as I read to the psychologists at Long Beach.

“It is apparent from the preceding discussion that no clear and distinct homosexual type emerges from this preliminary and admittedly superficial exploration. It may be asked whether on this test there are any items on which homosexuals do agree. I can report that there is only one such item, and it is that nudist colonies are not a threat to the moral life of the nation.” [Laughter.]

“This really has a very serious implication.” I can see we really got off to a bad start. [Laughter.]

“You may be surprised to learn”—you won’t be surprised to learn—“that one of, that, that one of the group agrees, and all the rest disagree, with the statement, ‘A sex pervert is an insult to humanity and should be punished severely.’ But this individual, who agrees with the statement, notes in the margin, ‘A homosexual is not a pervert.’”

Now, these are the major conclusions, and I think I’ve talked enough, and, uh, there’s a lot of other data here for you to ask questions, but, uh, and also to make comments and pick up at any point that you want to on this.

———

EM Narration: Dr. Hooker wanted feedback from Mattachine members on her invert paper, but she had an additional motive for talking to the Mattachine Society: she needed subjects for a new research project. Back in the 1940s, a gay friend had pressed her to prove what he knew to be true: that homosexuals were no crazier than anyone else.

———

EH: Sammy turned to me and said, “We don’t, we don’t need psychiatrists, we don’t need psychologists. We are not insane. We’re not any of those things they say we are. And it is now your scientific duty to make a study of people like us.

———

EM Narration: It took her a few years to find the time and the funding for a study like the one her former student and friend Sam From had lobbied her to do. By 1954, she had funding and time, but she needed men. She was planning a study that would question the very underpinnings of the sickness label, comparing the adjustment—or, well, relative sanity—of heterosexual and homosexual men. No one had thought to conduct such a study before.

The Mattachine Society was the perfect place to find the gay men she needed. It was a ready-made study group: ready, willing, and able to contribute to her research. When Dr. Hooker presented the results to the American Psychological Association in Chicago in 1957, it was momentous.

———

EH: It was held in a big ballroom in one of the big hotels. Um, and, um, the air was electric, it was just electric. And of course there were people—some, not too many—but there were some people who were saying, “Well, that of course, that can’t be right.” And they set off to try to prove that I was crazy.

EM: Why was it so electric?

EH: Uh, what was so electric about it? Well, if you’re challenging a long and commonly held position, and you know that there are thousands of lives at stake…

———

EM Narration: Dr. Hooker had delivered the assignment her friend had set for her over a decade earlier. Through a series of tests using accepted predictive techniques—and with a panel of esteemed psychiatrists who affirmed her findings in a blind reading of the results—she had proven that gay men were no crazier than straight men. The psychiatric consensus was shaken. But there was a gaping hole in her research.

———

EM: You didn’t duplicate your study for women, um, for gay women, lesbians.

EH: I didn’t what?

EM: Do the same—you didn’t do a similar study for lesbians.

EH: No. No.

EM: I’m curious as to…

EH: … why I did not. Well, I don’t think that it would—I don’t think that I could have done it as easily.

EM: Mm-hmm.

EH: Um, I, when—you know, they used to say to me, once the results were known and, and so on, and so on, and they would say, “Why didn’t you do, why didn’t you do for us what you did for the gay men?” And I said, “You didn’t ask me.”

EM: And the men did.

EH: And the men did. And of course that’s true.

———

Billye Talmadge: And she told us she could not, because, professionally, she, it would be, she’d be dead.

EM: Why is that?

BT: They would not, they would not accept it.

EM: Gay women didn’t exist?

BT: Not that gay women didn’t exist, but that a woman studying gay women would be highly, highly suspect on any, any, uh, information she gave. We, she was a very close friend. And she would come to all of our meetings and conferences and panels and things like this, but she never did a study on gay women.

———

EM Narration: We’ll never know exactly why Dr. Hooker didn’t include women in her research—whether it was because they didn’t ask, as she told me, or because she feared sexism and homophobia would undermine her findings, which is what Daughters of Billitis member Billye Talmadge said. But the aftershocks of Hooker’s groundbreaking study on men would reverberate across the gay rights movement. And while Dr. Hooker’s research didn’t immediately overturn the APA’s definition of homosexuality, it laid vital groundwork. Now someone else needed to pick up the ball and run with it.

Act three: We Are the Experts on Ourselves.

———

Frank Kameny: In the movement, the feeling was a level of uncertainty. We had to defer to the experts.

EM: Oh, you hated that, didn’t you?

———

EM Narration: Frank Kameny was a victim of the Lavender Scare. He was fired from his government job in 1957 because he was gay. The persecution radicalized him. In 1961 he founded the Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C. The new outpost of Mattachine was very much a reflection of Frank’s personality and his goals.

———

FK: My answer was, we are the experts on ourselves, and we will tell the experts they have nothing to tell us. But it took a few years to get that across.

———

EM Narration: Frank was both blessed and burdened with an unshakeable certainty about his position on any given subject. His brusque and uncompromising manner rubbed a lot of people the wrong way. But he was extraordinary in his vision for the movement. He was also very persistent.

———

FK: One of my fights—which I started in ’63, uh, and took 10 years to succeed and was picked up by others—was the fight against the American Psychiatric Association.

———

EM Narration: While Frank was champing at the bit in Washington, over at the Daughters of Bilitis, members Barbara Gittings and her life partner, the photojournalist Kay Lahusen, were also growing impatient with DOB and the posture of the pre-Stonewall movement. They were ready to buy whatever Frank was selling. Here’s Kay talking to me in 1989 about the tensions between the homophile old guard and Frank’s bold ambitions. Barbara can’t help but chime in, too. I’m sorry for the paper rustling—I think that was me wrestling with my notes.

———

Kay Lahusen: And, you know, it was Frank who said, uh, that we have to proclaim that in the absence of valid evidence to the contrary, we’re well. We’re not sick. And that the burden of proof rests on those who would call us sick. And then Florence Conrad of DOB said, um, that, uh, no one would listen to us. And Frank says, “So what? If no one listens…”

BG: “… we haven’t lost anything.” Right.

KL: “If someone listens, we’ve gained something.”

BG: And he said, “Even if it’s only that gay person out in Iowa…”

KL: Right.

BG: “… who feels encouraged by hearing somebody stand up and say this on our behalf, that’s a, that’s to the, that’s to the good.” Well, that made great sense to us. And we liked, we liked the, you know, the fervor behind this. And, and it seemed to be very common, good common sense. We don’t wait around for the experts to declare us normal.

———

FK: We started at that point to take on the American Psychiatric Association.

———

EM Narration: But the only people who could actually declassify homosexuality as a mental illness were the members of the American Psychiatric Association. So these activists who were hungry for, well, action needed to find a way to appeal to the APA’s members.

Act four: Outsiders on the Inside.

Dr. Judd Marmor was a member of the APA. He didn’t start out as an ally. Like the rest of his profession, he agreed with the sickness label. But when he heard Dr. Evelyn Hooker’s groundbreaking paper in 1957, he didn’t dismiss it out of hand. She was a good friend of his, and he admired her work.

———

Dr. Judd Marmor: When she made the statement that homosexuality was not an illness at the first time I heard her, I wasn’t prepared to go all the way. I was sympathetic to what she was saying, I wasn’t offended by what she was saying, but I wasn’t totally convinced. I still had a feeling that it was a developmental deviation, and that we were assuming—making a lot of assumptions about the so-called homosexual personality that weren’t warranted, uh, but I still wasn’t ready to assume that there was something other than a developmental deviation involved in it.

———

EM Narration: But over the next seven years, Dr. Marmor’s position evolved. And when a publisher approached him and asked him what he would like to write a book about, he knew he wanted to write about homosexuality.

———

JM: I said, “I feel that, um, my colleagues’ views about homosexuality are wrong.” And, um, he said, “Great, let’s do a book on that.” So I did. The book was called Sexual Inversion: The Multiple Roots—R.O.O.T.S.—of Homosexuality, and that was published in 1965.

———

EM Narration: Dr. Marmor invited a number of psychologists and psychiatrists to contribute to his book, including his friend Dr. Evelyn Hooker. Some of the authors were still writing in support of the sickness label, but Judd Marmor was growing increasingly uncomfortable with his colleagues’ views on homosexuality.

———

JM: What I did point out in that book is that the assumption that this was an illness was based on a skewed sample. That, uh, psychoanalysts only saw disturbed homosexuals in their offices. And I said if we made our judgment about the mental health of heterosexuals only from the patients we saw in our office, we’d have to assume that all heterosexuals were mentally disturbed. And I was appalled by the stereotypic generalizations that were being made about homosexuals in the various psychoanalytic meetings I was going to. I was still a young analyst. But I’d go to meetings and I’d hear about the, “the homosexual personality” and about the fact that homosexuals were vindictive, aggressive, couldn’t have decent relationships, were not to be trusted—all terribly nasty, negative, disparaging things. And I knew gay men and women, and this just didn’t make sense to me. And that’s one of the points I attacked strongly in my book: that this was a stereotyping of a group that really concealed a prejudice.

———

EM Narration: Dr. Marmor’s new outlook and his book got the attention of some in the APA.

———

JM: And it was considered a relatively revolutionary statement.

EM: You must have taken a lot of heat for that.

JM: Oh, I did. But, uh, one of the rewarding things is that at meetings of the American Psychiatric Association, psychiatrists began to come up to me and say, “Look, I want to tell you how much I appreciated your book, I’m gay.” Now, the psychiatrists whom I came to know, who ultimately formed a group within the APA which they called the GayPA…

EM: Who were some of the people then who were involved?

JM: I think I’d rather not mention their names, because some of them may never have come out of the closet.

———

Barbara Gittings: There had been for years a kind of GayPA meeting during the time of the annual APA conference. But it was very—a very closeted affair. They would meet privately off conference premises in a restaurant in the host city. And it was all gay psychiatrists, but they were definitely not open. And there were just beginning to be the stirrings among a few of this group, the GayPA, that they might want to do something a little more open in their own association, but still nothing very definite had happened.

———

EM Narration: Nothing very definite had happened—yet. But that was about to change. In separate interviews for my book in 1989, Dr. Marmor, Barbara Gittings, and Kay Lahusen shared the story of what happened next, so I’m going to step back and let them take it from here.

———

JM: We had some very, uh, dramatic confrontations. During the ’70s, the gay liberation movement became very, um, vocal, and began to appear at APA meetings, and demanded a voice.

———

BG: In 1970, a large group of feminists and a few gays invaded a behavior therapy meeting at the American Psychiatric Association’s conference, which was in San Francisco that year. They disrupted the meeting and said, in effect, “Stop talking about us and start talking with us.”

———

JM: These were days in which homosexuality was being treated by, uh, adversive therapy, by shock therapy, and things like that, and, uh, the gay people were justly very angry at that. They demanded that they be given a, uh, session in which they could present their views.

———

BG: The American Psychiatric Association conference managers are very smart people, and they are not about to let themselves get kicked year after year by some group that wants to invade to get its message across. So they turned around and the very next year invited gay people to be on a panel called “Lifestyles of Non-Patient Homosexuals,” which we informally called “Lifestyles of Impatient Homosexuals.” And this was the very first time that the American Psychiatric Association had even conceded that there were homosexuals who were not patients in therapy. Because every time the subject had been brought up in previous conferences, it was always, we were patients in therapy there for treatment. Well, this was a recognition that there are gays who do not come for therapy.

It was successful. It wasn’t a huge turnout, but it was a successful thing. And the next year, we were invited to have a panel.

———

JM: There was a head of the, um, lesbian movement at that time whose name I can’t—

EM: Barbara Gittings?

JM: Barbara. Barbara was there and, uh, the fellow from Washington…

EM: Frank Kameny.

JM: Frank Kameny was there. So Frank was on the panel and Barbara was on the panel and I was on the panel. It was a very dramatic session with this fellow from Philadelphia with a, with a grotesque mask on. Somewhere I have a picture of it.

EM: You do?

JM: If I can locate it, I’ll…

EM: If you can locate it, that would be wonderful.

———

BG: Oh, this is Dr. Anonymous at the American Psychiatric Association.

KL: I took that picture!

BG: That’s Kay’s picture. [Crosstalk.] Yes, that’s Kay’s photo. Well, at the left is myself, Barbara Gittings. Next to me is Franklin Kameny. And we were the two non-psychiatrist gay panelists.

EM: What was this, what was this event that you were speaking at?

BG: This was the American Psychiatric Association’s annual conference.

EM: This was in May of 1972.

BG: Um…

KL: Does it have my name on?

BG: This is from Judd Marmor’s collection.

EM: Judd Marmor gave that to me.

KL: Oh, we must have sent it to Judd Marmor.

BG: Here we were, Frank and I, and Kay said—this was all Kay’s doing—she said, “Well, look, um”—oh, yes, there were to be a couple of psychiatrists, I think Judd Marmor was one of them—and she said, “Look, you have psychiatrists who are not gay on the panel, and you have gays who are not psychiatrists on the panel, but what you’re lacking on the panel is gay psychiatrists, those who are both.” And she said, “Why don’t we try to get a gay psychiatrist.” Well, uh, the moderator was perfectly agreeable, but he said, you know, “Find somebody for me.”

And I made a number of calls to some of the people that I had made some contacts with, and nobody yet, nobody yet was quite willing to be that public.

EM: Why? What would have happened if…

BG: They feared, they feared, uh, damage to their careers. But finally I talked with this one man who said, “Well, I will do it, provided I am allowed to wear a wig and a mask and use a distort microphone.” And that’s what he did.

He was billed in the program as “Dr. H. Anonymous.” That was the way he wanted to be billed. And he was going to talk about what it was like to have to live in the closet because of career constraints as a gay psychiatrist. And I, what I did to back him up was to write to all of the others that I knew, gay psychiatrists, and say, “Please send me a few paragraphs about what it’s like to be a gay psychiatrist in the association. You do not have to sign it. I will read these at the APA convention.”

And I told H. Anonymous that I was going to do this so that he wouldn’t be the only one speaking in effect. There would be other voices behind him, even if their names weren’t attached to their statements. It went off marvelously. H. Anonymous got into his mask and…

———

JM: … and spoke into a, a microphone that concealed his voice, and admitted that he was gay. This was a, an unheard of thing to have done, and it was very dramatic.

———

Dr. H. Anonymous: I’m a homosexual. I’m a psychiatrist. I, like most of you in this room, am a member of the APA, and I’m proud of that membership. Tonight, however, I am insofar it is, as it is possible, a “we.” I attempt tonight to speak for many of my fellow gay members of the APA as well as for myself. When we gather at these conventions, we have somewhat glibly come to call ourselves the GayPA, and several of us feel that it is time that real flesh and blood stand up before this organization and ask to be listened to and understood insofar as that is possible.

I’m in disguise tonight in order that I might speak freely without conjuring up much regard on your part about the particular who whom I happen to be. I do that mostly for your protection. I can assure you that I could be any one of more than 200 psychiatrists registered at this convention or more.

———

EM: How do you mean that it came off very well? What was…?

BG: First of all, it was, the house was packed. And everyone, of course, wanted to see H. Anonymous, naturally. I think he’s the reason that the house was packed. And, let’s face it, the man’s physical size meant that I’m sure there were people who would recognize him, in spite of the microphone and the wig.

But he was willing to take that chance. He didn’t seem to mind that. He felt that he’d given himself sufficient cover. He made a very eloquent presentation. And then the statements that I read from other psychiatrists sort of clinched it. It was an extremely successful program.

———

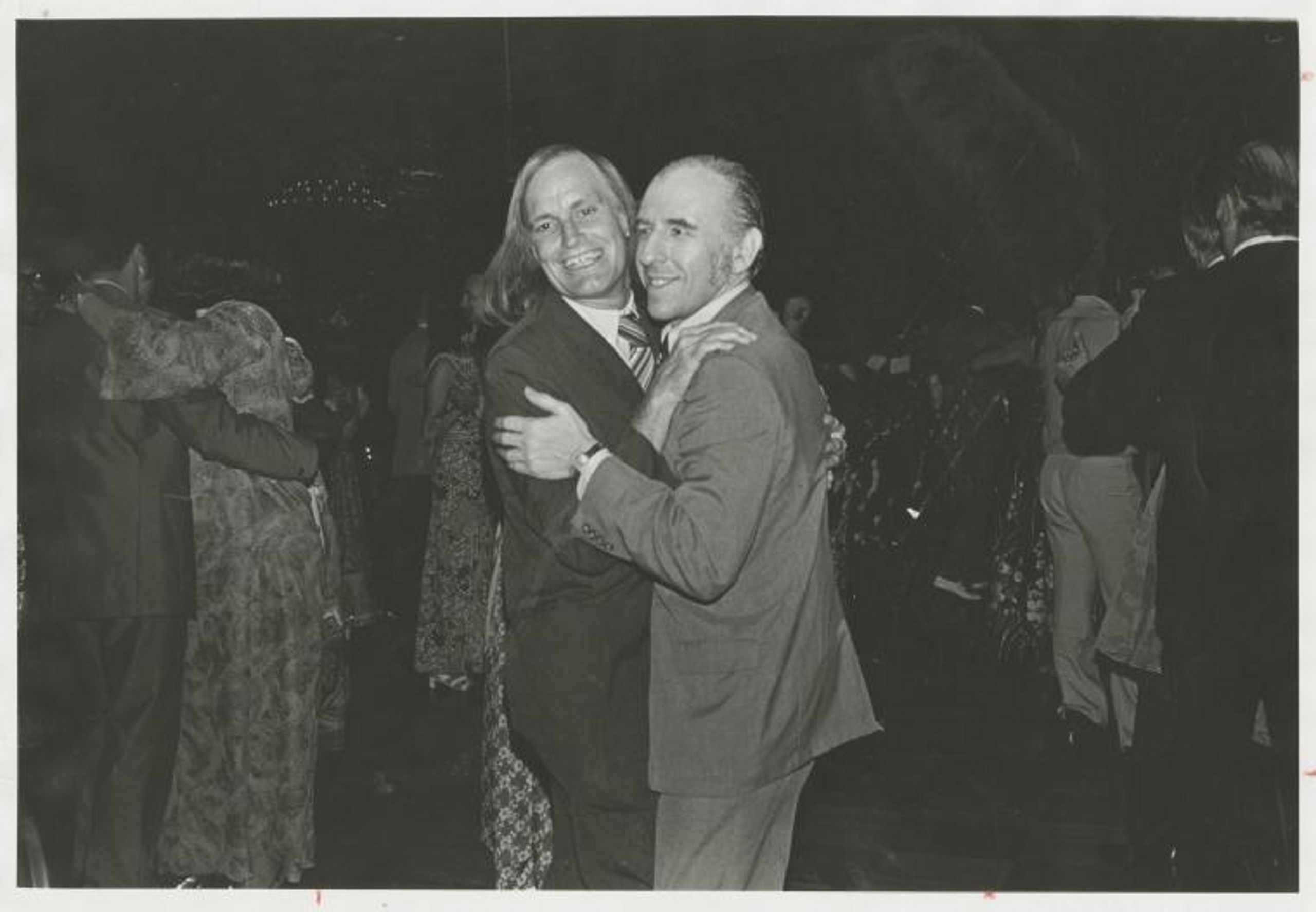

EM Narration: Thanks to activists rattling the cage from the outside, and allies providing cover and solidarity to the gay psychiatrists on the inside, it seemed as if the stuffy old APA was inching in the direction of change. As we wrapped up our conversation about that dramatic and consequential APA conference, Barbara and Kay insisted we look at one more photograph Kay had taken in Dallas back in 1972.

———

KL: I know in Dallas… [Crosstalk.]

BG: This is what the… [Crosstalk.] Yes. There’s a formal dinner as part of the conference activities each year. And Frank, as a guest of the association who was one of the formal speakers that year…

EM: Frank Kameny.

BG: … Frank Kameny, was given a ticket to this thing, and he invited Phil Johnson, a local gay activist, and they danced together. [Laughs.] Oh, that was wonderful. I think this one was probably one of the first public, uh, you know…

EM: Displays?

BG: … displays of, uh… Well, the psychiatrists, of course, they had to keep their cool. Nobody pounced on them and destroyed them. No, of course not, but I’m sure they were shocked by it. Anyway, Frank had a wonderful time. Phil had a wonderful time.

EM: Look at that.

BG: That’s Phil Johnson with Frank Kameny dancing away at the formal, at, at the formal dinner.

———

JM: And then a year later, we had an official debate. The debate about the DSM-III had already begun.

EM: DSM-III?

JM: The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. And the debate about whether or not homosexuality was an illness began. And at that, at this official debate, which was, um, uh, chaired by Bob Spitzer—but on the platform, uh, representing, uh, various points of view were myself; Richard Green, he’s the man who wrote The Sissy Boy Syndrome; Robert Stoller; and, um, uh, Charles Socarides and Irving Bieber. This was a very, very dramatic debate, which was attended by several thousand psychiatrists. There was also a young man who, um, whose name I can’t remember. He was the spokesman for the, uh, for the caucus—very outspoken—who, who made a talk also and said, “Stop it, you’re making me sick.”

———

EM Narration: Act five: You’re Making Me Sick.

———

Ron Gold: Since I’ve joined the gay liberation movement, I’ve come to an unshakeable conclusion. The illness theory of homosexuality is a pack of lies concocted out of the myths of a patriarchal society for a political purpose.

———

EM Narration: Honolulu, May 1973. The young man on stage at the APA’s annual meeting was Ron Gold, a member of the Gay Activists Alliance, the Gay Liberation Front, and the brand new National Gay Task Force.

———

RG: Psychiatry dedicated to making sick people well is the cornerstone of a system of oppression that makes gay people sick. To be viewed as psychologically disturbed in our society is to be thought of and treated as a second-class citizen. And being a second-class citizen is not good for my mental health.

That isn’t the worst thing about your diagnosis. The worst thing is that gay people believe it. Nothing makes you sick like believing that you’re sick.

Take the damning label of sickness away from us. Take us out of your nomenclature. Work for repeal of the sodomy laws, for civil rights protections for gay people. Most important of all, speak out. You’ve allowed a handful of homophobes to tell the public what you think. It’s up to you now to get on the late-night talk shows and write for the newsweeklies as they do. You’ve got to tell the world what you believe, that gay is good.

———

EM Narration: Ron Gold’s plainspoken, proud, defiant speech brought the voice of gay liberation to the APA debate stage. Seven months after that speech in Honolulu, four and a half years after the Stonewall uprising, 10 years after Frank Kameny turned his attention to the psychiatrists, 16 years after Dr. Hooker presented her landmark study in Chicago, and 23 years after the Mattachine Society was founded, the American Psychiatric Association changed its guidelines in the DSM and, “with the stroke of a pen,” cured millions of gay people who were no longer ipso facto mentally ill.

———

EM: What of the people who say, and I’ve had this said to me, that the only reason the psychiatrists made the change was that they were strong-armed by a bunch of gay activists, uh, and in fact, it wasn’t a true assessment of the feelings of the psychiatrists—uh, that they were forced into doing it.

BG: I wouldn’t say that’s a fair assessment. I do think that we, we raised the issue publicly within the association. Frank and I did it, and then others joined us and also did it. Uh, if we hadn’t made some noises, I think it would still be locked in committee.

Um, I think we moved its work much faster and much further. I, I would not say it’s fair, it’s not fair to say that we strong-armed them. Uh, that’s not fair to the psychiatrists. They, they are not going to be strong-armed into something. But if they know…

KL: But it was a time for radical chic and you could get a certain, you could get ahead by certain radical tactics…

BG: But not when it came to making basic decisions, like the board of trustees vote to remove us from the DSM manual.

KL: They’re never totally immune to, uh, …

BG: I think, I think that this, I think what really happened is that they knew they were wrong. In their hearts, they knew that this was not right and not fair. And that they, sooner or later, they would have to abandon the old position on homosexuality.

And they might as well do it sooner rather than later because then each revision of the DSM, uh, is about a 10-year gap. And they could, I don’t suppose they cared for, uh, the prospect of the, the, uh, uh, nip-ups that we’d be doing if they didn’t…

EM: The what?

BG: The nip-ups.

EM: What is that?

BG: Nip-ups. Uh, antics. Uh…

KL: Zap tactics.

BG: Zap tactics and whatever else we might be doing, um, to, you know, to move them along on the issue.

KL: Like early ACT UP tactics.

BG: I don’t have, I don’t have any qualms about raising the issue. I don’t think it was too much and I don’t think you can say that they were pressured into doing something they would… If they knew it was really wrong, they wouldn’t have budged. But I think they knew their position was wrong and that they would have to be budged. And maybe this was an easy way out.

KL: But it’s always been a more political decision than a, uh…

BG: … medical one. It never was a medical one. And that’s why I think the, the, the action came so fast. After all, it was only three years from the time that feminists and gays first zapped the APA at a behavior therapy session to the time that the board of trustees voted to, uh, approve removing homosexuality from the list of disorders, mental disorders. And it was a political move. Sure they, it was that. But that’s because it was a political move all along. It never was a scientific statement to label us sick.

KL: I think the psychiatrists were losing ground on a number of fronts. And I think they just didn’t want to be left behind.

———

EM Narration: Some psychiatrists didn’t mind being left behind. There were still holdouts firmly opposed to the reclassification. After the December 15 decision, a group of psychiatrists insisted on putting the nomenclature change to a vote by the whole membership of the APA. It was unprecedented, and it didn’t work. The vote affirmed the trustees’ decision to pass the December 1973 resolution that removed homosexuality from the list of mental illnesses.

Act Six: Vanishing Point.

It’s interesting, in historical perspectives, how some events get bigger the further you get away from them, and some kind of shrink. Delisting homosexuality had a fundamental effect on the movement for LGBTQ rights. Dozens of struggles and victories depended on us no longer being automatically dismissed as mentally ill. Or tortured for it. But even when I was interviewing Barbara and Kay back in 1989, we had a sense that later generations might not understand what a seismic change reclassification had been.

———

BG: The difference that it made was, it took an enormous burden of operation off our backs. So that we could stop put—throwing so much of our resource into fighting the sickness label. And could now devote some of that energy and money to other issues that were, that were really big and really hurting.

The effects were not necessarily felt overnight, but you could see that, uh, by the end of the ’70s, some six or seven years after the decision in APA, we were no longer putting so much energy into fighting the psychiatrists and the sickness label.

EM: And today it’s hardly talked about.

BG: It’s hardly talked about. Now, it’s okay… [Crosstalk.] I’d rather, I’d rather… [Crosstalk.] No, but I would… In a way you can argue with people who say that you’re immoral because you can say, look, there’s so many kinds of morality. There are no absolutes, and you and I will agree on, on most things, and we will disagree on this one, but you can’t enforce your morality on me.

The sickness label supposedly had the, the cachet of, of indisputable science, which made it a lot harder to deal with in the, in the, with the general public.

EM: That’s right.

BG: It was easy for people to say, “Oh, those people are sick.” And now they had to come up with other reasons. So now they’re coming out with more basic reasons: “I don’t like you. I don’t like the way you live. I think you’re immoral. I think you’re rotten.” Well, all of that is more honest than this nonsense about you’re sick.

EM: That’s right. That’s right. It’s forced people to be more honest.

BG: Exactly.

———

EM Narration: It’s been a half-century since the American Psychiatric Association decided that homosexuality was not a mental illness, but that reality hasn’t entirely lifted the burden for many LGBTQ young people coming of age today. They still suffer in a society that stigmatizes people because of their sexuality or their gender identity—when who they are doesn’t align with the heterosexual and gender binary norm. That’s where we’ll pick up the conversation in our next and final episode in this miniseason, when I sit down with mental health experts to ask them about the legacy of the sickness label, the mental health challenges facing LGBTQ people today, and we’ll also talk about hopeful futures for LGBTQ youth.

That’s next time.

———

This Making Gay History miniseries was produced and written by Making Gay History’s founding editor, Sara Burningham, and Anne Pope. Anne also mixed this episode. Tyler Albertario provided archival research support. Our studio engineers were Michael Bognar and Charles de Montebello at CDM Sound Studios. Our music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Many thanks to our hard-working crew at Making Gay History, including deputy director Inge De Taeye, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter.

Thank you to the New York Public Library Manuscripts and Archives division for their ongoing assistance. Thanks also to the Pennsylvania Historical Society, which houses the papers of Dr. John Fryer, also known as Dr. H. Anonymous. Thanks also to Patrick Sammon and Bennett Singer, producers and directors of the exceptional documentary Cured.

Making Gay History is made possible thanks to the ongoing support of the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, the Calamus Foundation, and Christopher Street Financial. We’re deeply grateful to Patrick Hinds and Steve Tipton for their two-year grant in support of Making Gay History’s mission to bring LGBTQ history to life through the voices of the people who lived it. And thank you, as well, to Ty Ashford and Nicholas Jitkoff, Christine and Bryan White, Bill Kux, the Kipper Family Foundation, the Marcus Family Foundation, and the late Linda Hirschman for their generosity.

To learn more about the people and stories we’ve featured over the past seven years, please visit makinggayhistory.com where you’ll find links to additional information, archival photos, as well as full transcripts for all our episodes.

I’m Eric Marcus, so long until next time.

###