Coming of Age During the AIDS Crisis — Chapter 5

Episode Notes

“You’re doing too many stories on AIDS.” The word had come down from on high at CBS This Morning. Eric didn’t want anyone to think he was biased, but as the only out gay person on the production staff, he felt an obligation to cover the growing epidemic.

———

For a comprehensive overview and useful links related to HIV and AIDS, consult this HIV.gov timeline.

For a New York City-specific timeline, see this New York magazine article. (Please note, however, that the Patient Zero theory referenced at the top has since been discredited; for more information on the subject, watch the documentary Killing Patient Zero.)

This chapter covers mid-1986 through 1988. During that time, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), 54,011 new cases of AIDS were reported, in addition to 23,117 deaths. This brought the cumulative totals to 82,764 reported cases and 46,344 deaths in the United States. Although a blood test for HIV was available by this time, the actual numbers remain unknown.

In 1987, the CDC changed its definition of AIDS to accommodate the use of HIV antibody tests and reflect a greater understanding of the disease. Learn more about the CDC’s changing definitions of AIDS here.

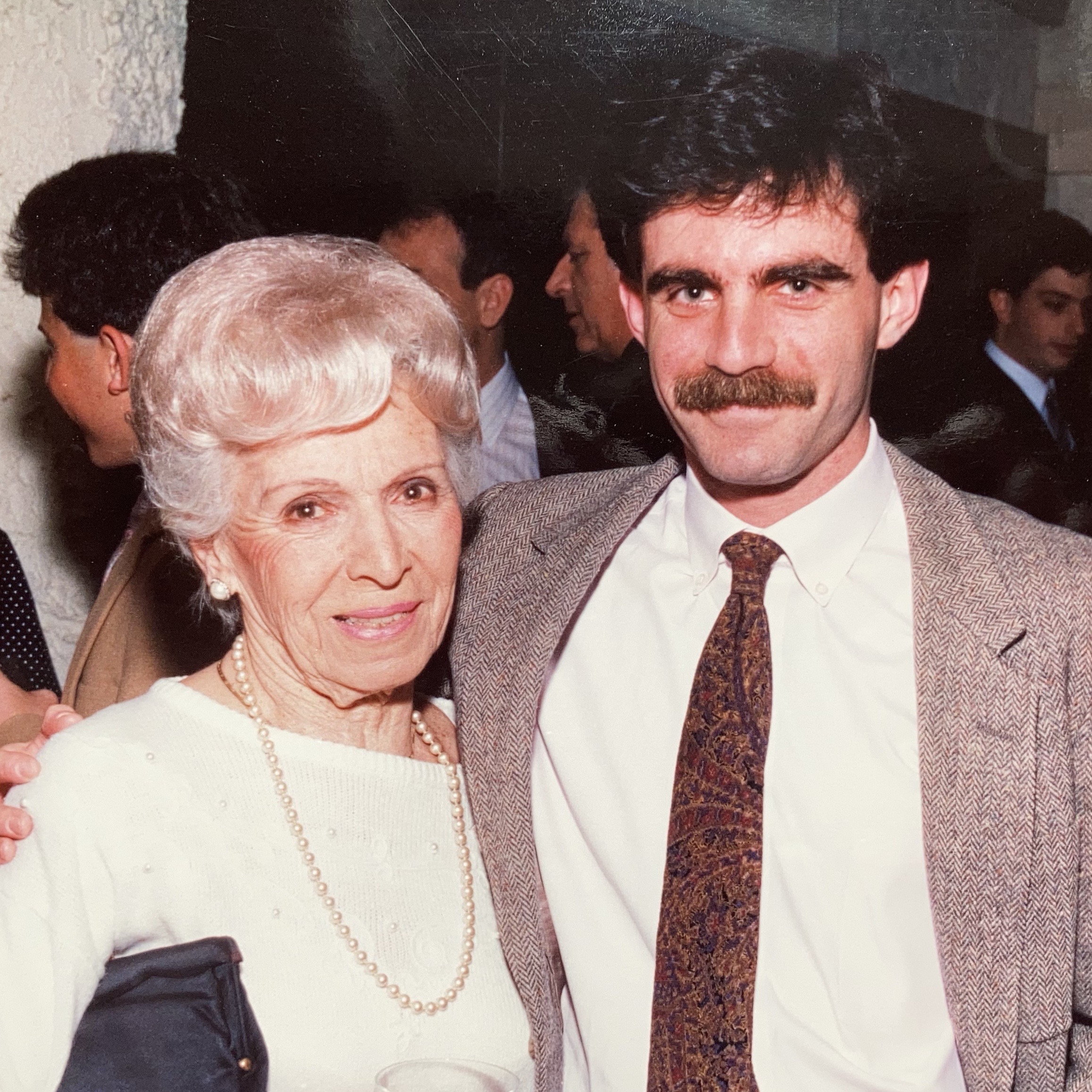

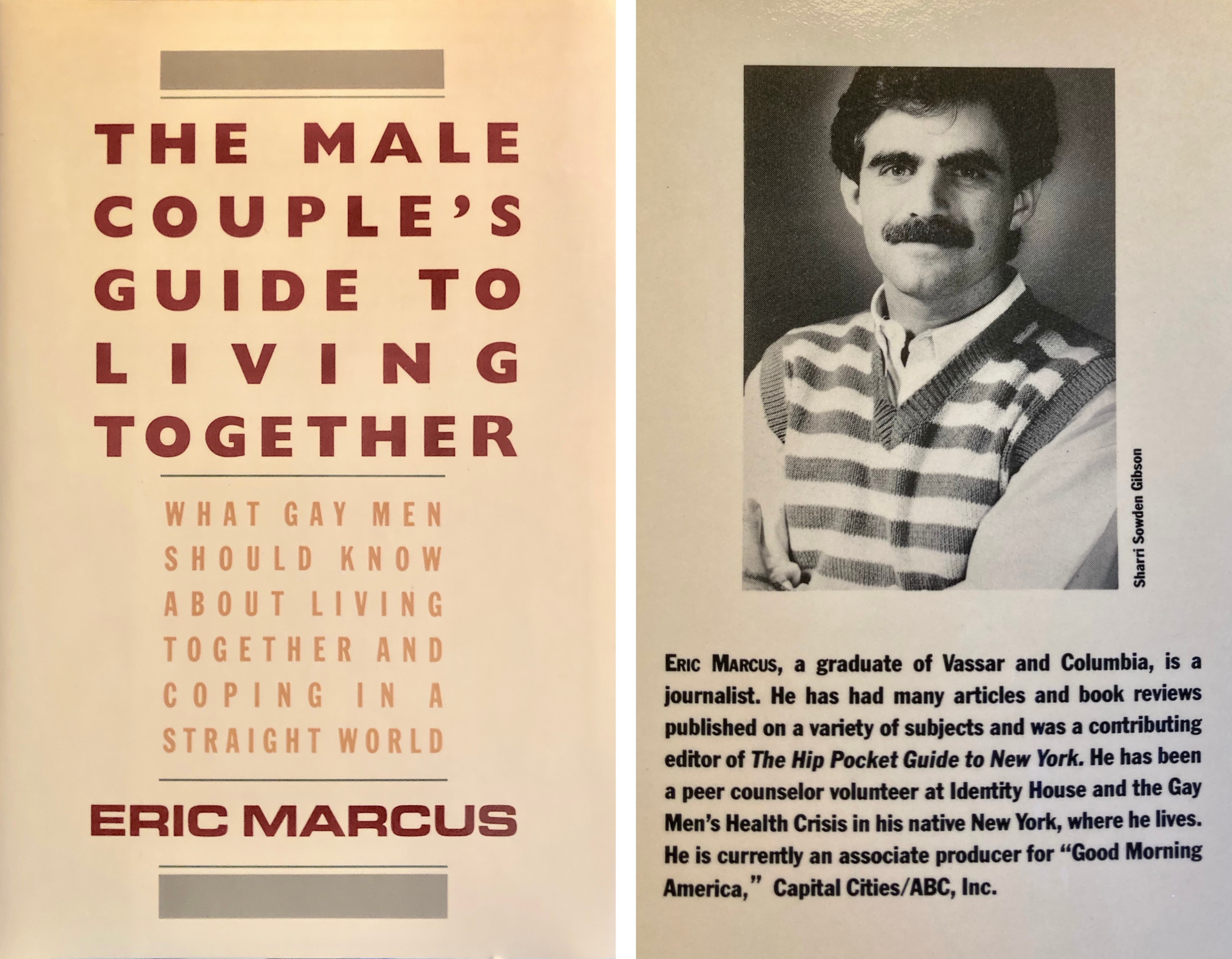

In the episode, Eric talks about coming out to his grandmother after the publication of his first book, The Male Couple’s Guide to Living Together: What Gay Men Should Know about Living Together in a Straight World. Read a book tour interview with Eric in this Bay Area Reporter article from March 1988. Watch Eric narrate the story of his coming out to his Grandma May in this video.

When Eric interviewed for a job at Good Morning America, his prospective boss asked him to take The Male Couple’s Guide off his résumé. This kind of pressure was not uncommon and compelled many LGBTQ people to live a double life in and out of the closet. Learn more about the history of sexual orientation discrimination in the workplace here.

Eric worked at both ABC News and CBS News at a time when the mainstream media was not yet comfortable or fair in reporting on LGBTQ people. Read about the media’s reporting during the early years of the AIDS crisis here, do a deeper dive here, or read this article on the history of the New York Times’s AIDS coverage. Edward Alwood’s 1996 book, Straight News, offers a historical overview of the gay community’s efforts to get the mainstream news media to responsibly report on lesbian and gay people and covers the history of the lesbian and gay press from the Mattachine Review to the Advocate.

At ABC’s Good Morning America, Eric co-produced a segment on Mothers of AIDS Patients (MAP). Among MAP’s most prominent members were Barbara Peabody, Mary Jane Edwards (for her son Greg), Barbara Cleaver, and Miriam Thompson Slater. Learn more about MAP here.

Also at Good Morning America, Eric worked on a profile of Ryan White, who was diagnosed with AIDS following a blood transfusion in December 1984 at the age of 13. In 1985, White was banned from attending his local school in Kokomo, Indiana. The White family fought the ban in court and had it overturned, amidst enormous media attention. The case helped to dispel myths about AIDS transmission through casual contact, and White became a cause célèbre, drawing the attention and support of celebrities, including Michael Jackson and Elton John.

White died from AIDS-related complications on April 8, 1990. Learn more about his life in this short documentary or this 2016 interview with his mother, Jeanne. Four months after White’s death, the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency (CARE) Act was passed by Congress to provide HIV-related care and treatment to underserved, low-income Americans.

On March 10, 1987, the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power (ACT UP) was formed at New York City’s LGBT Center after a fiery speech by activist and playwright Larry Kramer. Their first demonstration took place on Wall Street that same month to protest the high cost of AZT, the only approved AIDS drug at the time. ACT UP is a grassroots political group still working today to end the AIDS epidemic. To learn more, read Sarah Schulman’s Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993, watch the documentary United in Anger: A History of ACT UP, or listen to interviews through the ACT UP Oral History Project.

In 1988 Rick Kot, an editor at Harper & Row, invited Eric to write a book proposal for an oral history of the gay and lesbian civil rights movement. The book was published in June 1992 under the title Making History and later revised and released as Making Gay History. Find out more in this conversation between Eric and Kot.

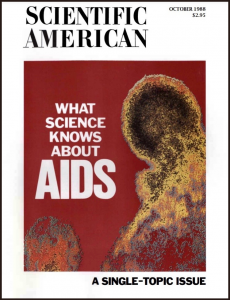

In the episode, Eric references the October 1988 issue of Scientific American, which was entirely devoted to AIDS. You can read it here.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and in this season of Making Gay History, I’m revisiting my past to share some of my experiences from the 1980s, when the AIDS epidemic tore through my community. All too many people didn’t make it out alive; life would never be the same for the rest of us. This audio memoir is about that time and those people.

This is chapter five: “In or Out.”

It’s the Friday before Gay Pride Day in June of 1986, and I’m sitting in a hospital room with our friend Mark, the bow tie-wearing graphics designer from work. I’m suited up in a mask, gloves, and protective gown. It’s to protect him, not me. His immune system has been decimated and he’s battling pneumocystis pneumonia. His breathing isn’t great, his chest heaving as he sips air through an oxygen mask. I’ve brought him some watercolors so he can paint. We’re talking about what he’s gonna do when he gets out of the hospital—like going back to work and maybe a summer getaway to the countryside for the four of us. These are as much plans as they are daydreams; we’ve all become familiar with the hospital admission and discharge dance: one infection suppressed, live to fight the next one…

Two days later, Barry and I are just home from the Pride March. The light on the answer machine’s blinking. Barry presses play while I take off my shoes. I hear Mark’s partner’s voice. Not the words, his voice. I try to block it out. I don’t want to hear the rest of his message. It’s too late. Mark is dead.

———

Eric Marcus: And then Barry and I, uh, planned his memorial service at the Vassar Club, um, which was located at the Lotos Club, which is a fancy private club on the Upper East Side, which had never seen an AIDS memorial before. Barry came up with the idea of a—we called it the balloon benediction. We got all these helium balloons that we brought with us to the, to the Lotos Club, and each one had a little plastic bow tie attached to it. And after the service, we went out to Central Park, and we released the balloons with these little bow ties on them. That for us was, um, uh—we couldn’t, we couldn’t say that it wasn’t people like us at that point.

———

EM Narration: I spend the rest of the year working like crazy on my book, The Male Couple’s Guide. Writing a guide to living together when so many around us were sick and dying was an escape for me. The book was aspirational. Let me read you the full title: The Male Couple’s Guide to Living Together: What Gay Men Should Know about Living Together and Coping in a Straight World. It sounds so vanilla now. But in that swirl of uncertainty and sadness, I wanted a textbook for living and loving—to build a bridge to a hopeful future. The book is based on interviews with 20 couples. I record them on my junky tape recorder, never knowing exactly what people were going to say, but astonished by how eager everyone was to share their stories. No one had asked them before. And I was all ears, hearing stories about how these couples met and how they navigated their relationships at home and out in the world, where being an out gay couple was still exceptional.

Listening back to those interviews 35 years later, they are so of their time: the sound of people finding their way—including me…

———

Speaker 1: Want me to start?

EM: Doesn’t matter.

Speaker 1: I’m 44. And, um, we met about eight and a half years ago, and, uh, I was married at the time.

Speaker 2: But we went down to the bar, and we were dancing and things, and I suddenly stopped and grabbed this man and said, “Are you coming home with me or not?”

Speaker 3: Why not.

Speaker 2: And, uh, he came home with me and we’ve been together ever since.

Speaker 1: You know, I, I reached the point where I realized in my marriage that something wasn’t right. And there was something that, you know, that I was missing, that I was looking for. And it turned out to be men.

Speaker 4: I could be a bitch on wheels, and I could be so hurt by that, that I, uh, looked to hurt him back in some other subtle ways—you know, cut him up into little cubes and feed him to the sharks because of the hurt that I felt. But, luckily, I, I wasn’t playing those kinds of games with him.

Speaker 5: This AIDS thing is just frightening beyond belief. I feel, I feel very healthy. I feel I don’t have a worry about it. Doesn’t mean I’m not careful, but I don’t have a worry about it. Justin has some worries, I think, though.

Speaker 6: Well, I don’t—I, I think I’m just more cautious than he. I don’t know that I’m so worry-worried, you know. I have friends whose sex lives have been totally destroyed by it. You know, imagine, I mean, feeling guilty enough about having had a little fling and then killing your lover with that fling.

Speaker 7: I guess the downsides have been over the usual things, have been over money and, you know, making ends meet. Uh, tensions run high when you, when you’re short on cash, you worry about things like that, and it’s easy to get in your thoughts. You sometimes disagree on how to raise kids and…

Speaker 8: It wasn’t till recently that I met really long-term relationships—15, 20, 30, 40 years…

Speaker 9: Well, hence my comment. The other problem with, with lack of gay role models is that gay couples, because of the environment, frequently just disappear. I mean, they’re just, they’re never heard from again. You know, and they go off, you know, to—you know, the age-old thing, you know, if you’re single you live in Manhattan, if you’re, you’re a duo you live in Brooklyn.

Speaker 8: If you’re a what?

Speaker 9: A duo.

EM: A duo, right.

Speaker 10: And the new house will have one bedroom. And I’m, I’m…

Speaker 11: What the hell.

Speaker 10: Oh yeah, you know. And it’s stupid to go through anything other than that. If that’s a problem for anybody…

Speaker 11: That’s their problem.

Speaker 10: … we will, we will sense it. No, it can be our problem. We will sense it and that side of the house that is, in effect, the private side of the house will not be shown. That’s very simple.

Speaker 12: You know, you can’t show up with a…

Speaker 13: With your husband…

Speaker 12: … with your husband at a black-tie benefit, you know…

Speaker 13: Whereas at Vogue anything goes.

Speaker 12: See, that’s the other thing. With him it’s totally different because on the reverse, he wears [inaudible] because he’s very—and he has my picture on his desk.

Speaker 13: Two pictures on my desk.

Speaker 12: He has, you know, he doesn’t have to worry about that at all.

EM: Also, I mean, there must be an assumption that if there’s a problem, we’re going to work it out.

Speaker 14: There haven’t been problems.

EM: Okay.

Speaker 14: Amazingly enough. There have not been problems.

Speaker 15: I think that’s an aspect of the fact that we’re extremely complicated people, and that we can roll around a little bit because, in theory and in practice, we agree. We know what we want, which is we want to be together in the happiest possible way for the rest of our lives. And that we will do what is necessary or not do what would interfere with that prospect.

———

EM Narration: I handed in the manuscript for The Male Couple’s Guide in January 1987.

———

Shane O’Neill: We didn’t really talk about, like, how exciting was it when your first book was published.

EM: I remember the moment that I opened the envelope that had the first copy of The Male Couple’s Guide. And I sat down in our big beige chair, which had been my mother’s big beige chair, and held the book in my lap as if it were a newborn child. It was the ugliest cover you’ve ever seen—all text—they wouldn’t let me use any images of men. And I was so proud of myself.

But I also knew in that moment that I was gonna have to tell my grandmother that I was gay because I was gonna be going on a tour for the book. Um, I put myself in the position of having to come out to one of the most important people, if not the most important person, to me in my life, um, who I loved, who loved me. And, um, I was gonna have to tell my sister, too.

———

EM Narration: Grandma May and I had a special relationship from the very beginning. My grandmother told me that when I was in the pulling-myself-up-on-the-frame-of-my-crib stage, that as soon as she came through the door I jumped up and down in jubilation and made all the happy sounds a baby can make before they have words. That feeling never went away. Growing up in a family where my parents were at war with each other, my grandmother was an anchor of stability. Childhood overnights in Brooklyn were wrapped in crisp sheets, fluffy comforters, and hugs.

Even in my late 20s, I was a weekly dinner guest at my grandparents’ modest apartment in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. I never arrived without flowers in hand or left without a care package that included a desiccated roast chicken and a little bag of almost inedible homemade dietetic raisin cookies. My uncle called them pebbles. My love for my grandmother had nothing to do with her cooking.

We were cut from the same cloth. Extremely judgmental. Fastidiously neat. Minimalists when it came to design. Obsessed with good lighting. And we had a connection that may or may not have had bearing on our relationship. I was the son of her son who killed himself. And she was the mother of my dead father. Whatever the connection, I loved her more than anyone who walked the planet. More than my mother. Even more than I loved Barry, but I never told him that.

I’d written a book. I wanted to share that with her. I was proud of The Male Couple’s Guide. And I also didn’t want her to find out I was gay from the TV or radio or a neighbor once the book came out. Some of my family members were not in love with the idea of telling her my truth. My grandparents were in their mid-80s and they’d say: “Don’t tell your grandmother. It’ll kill her. Don’t destroy her image of you. She’s old, how much longer could she live anyway?” My grandfather was already well into dementia, but my grandmother was sharp as a tack, and keeping my sexuality hidden from her had required considerable emotional and practical gymnastics.

———

EM: She and my grandfather came to visit our apartment, and it was a two—allegedly a two-bedroom apartment. It had a tiny little room off the kitchen and it had a big bedroom upfront. Barry was six years older. He had a real job. I think I must have been in graduate school at that point—uh, yeah, I was. And we made up the rooms to look like the little room was Barry’s room and the big room was my room. And my grandparents—oh, it was so embarrassing…

———

EM Narration: It made no sense that Barry was relegated to a six-and-a-half by eight-and-a-half-foot roomette with no closet. When I gave my grandparents a tour of the apartment, they just nodded and didn’t ask questions. I should have been relieved, but I felt sick to my stomach. It’s what secrets do to your insides.

It’s a Saturday afternoon at the very beginning of 1987 when I arrive at my grandmother’s front door, my heart pounding, and despite the cold, my shirt is soaked with sweat. I’ve timed my visit to coincide with my grandfather’s weekly trip to the library. I’m hoping she already knows. That Grandma May has already put it together. I hadn’t had a girlfriend since freshman year of college back in 1976. Barry and I had been living together for the past three years. I’d even brought him to my brother’s wedding.

We’re sitting in the little TV room, just inches apart. Usually it’s cozy. Right now I feel like I’m going to suffocate. “Grandma, you know that Barry and I are more than friends.” From the look on Grandma May’s face, it’s very clear that she has no idea what I’m talking about. I take a deep breath. “Grandma, I’m gay, and Barry and I are a couple.” Grandma’s expression doesn’t change. She’s not a crier, at least not when anyone’s watching. Her eyes are full, but her cheeks are dry. We don’t say much after that or through lunch, but before I leave, Grandma hands me a bag with a chicken and cookies. She hugs me, and tells me that she loves me. Her voice is flat. I think she’s in shock.

———

EM: Um, and now that I’m thinking about it, Grandma said, “You better talk to your sister.”

Heidi Katz: Yeah.

———

EM Narration: That left Heidi, my big sister. We had drifted apart after our father’s suicide, and she’d been living in Maryland for the past 12 years or so. It just seemed easier not to say anything to her until I absolutely had to.

———

EM: I specifically called you and asked you to meet me in Washington to have a conversation. Um, and I, I remember sitting with you on the Mall in Washington.

HK: That’s exactly what I remember. And we were sitting on this ledge, and I think there was water right behind us. And you telling me, and me thinking, wow, why didn’t Eric come out and tell me about this before? I am so hurt. And he’s telling me that I’m the last one in the family that he’s actually telling this to.

EM: And that felt terrible, but there was also, there was no going back. I couldn’t go back in time.

HK: When in fact I pretty much had put it together that this was a serious gay relationship. And that was your—part of your identity, of who you are.

———

EM Narration: Heidi and I had not talked about that moment in over three decades. We’re much closer now than we were then, but still, we’d never discussed it.

———

EM: And I wonder, did you ever talk to Grandma about this?

HK: Hmm. Not—yes. Yes, yes, yes. Yes, I did. Because she said, “I would never give up my grandson. I would never give up my Eric.” So, you know, she would never, never sacrifice that. So, yes. Yeah. She made a proclamation, a declaration to me, very, very clearly on the phone, that there was absolutely no way that any parent or grandparent should sacrifice and break that relationship.

———

EM Narration: It’s hard to put into words what that unconditional love meant. Still means. I first came out to myself in 1975 when I was 16. In other words, I said to myself, although not out loud, I’m gay. It was another year before I said that to another person—to my little brother, Lewis. And since then I’ve come out more times than I can count—to family, friends, coworkers, strangers on planes who ask questions that require it. And it always scares me. Despite publishing books about gay life and history, despite hosting this podcast, coming out still makes me anxious.

It’s hard to unlearn the fear, to forget the pressure to keep quiet. But—and I know exactly how corny this sounds—Grandma May’s enduring fierce love has helped guide me through it all.

After handing in the manuscript for The Male Couple’s Guide, it was also time to find a job. I’d spent the advance, the book wouldn’t hit stores for another year—I needed a paycheck. I really wanted to work in TV journalism, in the mainstream of the mainstream, on one of the morning shows. To my mind, Good Morning America was the mothership. My prospective new boss looked over my resume at the interview. He asked if I could remove any mention of The Male Couple’s Guide. He had no problem with me being gay, he said—he was gay and out himself—but he thought his boss might have a problem with it. At 28 I was going to be a published author, and now I was being asked to pretend it wasn’t happening. But it wouldn’t be the first time I’d had to hide my identity to get a job. What could I do? Reluctantly, I revised my resume, and I got the job.

I dress up for my first day of work, tie and a blazer, and just about skip down Broadway to Good Morning America’s offices. I was very excited. I get on the elevator with a short old guy in a suit. The doors close and he asks, “Who are you?” I introduce myself and tell him it’s my first day as an associate producer for Good Morning America. He introduces himself: he’s the vice president for morning programming at ABC. My boss’s boss’s boss. Oh.

“What were you doing before you got hired?” he asks. I want to tell him about my book. I hesitate. Then I say, “Do you want to know the truth or what’s on my resume?” He smiles. “Why don’t you come to my office when you get settled in and you can tell me.”

Day one. I haven’t even sat down at my desk yet, and already the deceit’s unraveling. I explain to my boss what happened in the elevator and then go down the hall to the big guy’s office and tell him about the book. I’d thrown my boss under the bus, and made an enemy. Not a good move on your first day. But I just didn’t want to have to pretend I was someone else. And I was angry that I’d been asked to.

Ever since journalism school I’d been warned that doing stories about AIDS or about my community could damage my career, and I didn’t want to be accused of bias, but the epidemic was all around me. Every day at breakfast, Barry and I read the obituaries in the New York Times. We jokingly referred to them as the gay men’s sports pages. Super dark, but it was a morbid ritual—tracing the contours of the epidemic in the death notices. Kind of like a 1987 equivalent of doomscrolling. Men cut down in the prime of life shrunk to a few lines of copy, littered with euphemisms to mask the real cause of death, to sweep relationships and identities under the carpet. “He died at home, aged 36. He died of pneumonia. Of organ failure. Or cancer. He is survived by his mother, his two sisters, or a companion.” You didn’t have to be Sherlock Holmes to guess what was left out. It should have made me so angry—all of it. Mostly it made me sad—and scared.

I was never an activist. I lasted five or ten minutes at my first and only ACT UP meeting. The AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power—a potent political force that harnessed so much grief and rage—was founded in March of 1987. I went along to a meeting at the Gay Center in Greenwich Village. The raw emotion terrified me.

But at work, it felt to me like I was often perceived as exactly that: an activist. I felt like I couldn’t win. I wanted to report on the AIDS crisis because I was gay, but because I was gay, I would be accused of bias. Over the next year and a half, with stints at Good Morning America and CBS This Morning, I’d find myself in that bind over and over again. I loved my job, I wanted to build a career. But navigating a system that had little interest in, or capacity for, honest and clear reporting about the epidemic or fair representation of gay people was, at times, head-spinning.

———

C. Everett Koop: You must remember that our experience with AIDS is barely six years old. It all began with only five reported cases in June of 1981, uh, to a cumulative total as of last week of nearly 33,000 cases of people with AIDS. And over half of them have already died of the disease, and most of the rest apparently will.

———

EM Narration: This is U.S. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop addressing the National Press Club on March 23, 1987.

———

CEK: Last year, more than 13,000 new cases were added to the total. And this year, we expect an additional 23,000. By the middle of 1991, a decade after the first few reports came in, we expect that a quarter of a million Americans will have contracted AIDS, a disease that so far has a mortality rate of essentially a hundred percent. Make no mistake about it: AIDS is fatal and AIDS is spreading.

———

EM Narration: The surgeon general wasn’t mincing his words. It was well past time for more honest conversations at kitchen tables across the country and on morning news shows. In the spring of 1987 I was assigned to a five-part special series on Good Morning America about being single in America. The original outline didn’t include anything about AIDS. How could we do a series on being single in America in 1987 without addressing AIDS? And that meant including gay men. My boss agreed and got it approved.

———

Joan Lunden: It is now 39 minutes after, and Kathleen Sullivan is here with part two of her series on what it means to be single in America today.

———

EM Narration: The segment was called “Singles and Sex.” Joan Lunden was the Good Morning America cohost and Kathleen Sullivan was the special ABC News correspondent assigned to the series. I wish you could see Joan and Kathleen’s matching voluminous hair helmets, complete with sprayed-in-place bangs. Think Joan Cusack from the movie Working Girl.

———

Interviewee 1: The whole AIDS scare, epidemic, whatever you want to call it, is going to revolutionize American society. It affects everything.

Interviewee 2: Because of AIDS I’ve had to make some very serious and some, in some ways, very, very difficult changes in my patterns.

Interviewee 3: The, uh, one-night stand of two years ago may be the person they wake up next to in the hospital two years from now. And it’s scary.

Kathleen Sullivan: The AIDS epidemic is most evident in cities like San Francisco—cities with large gay populations. In New York City, the disease is the leading cause of death among men 25 to 44, and among women in their late 20s.

Mathilde Krim: It may be 10 years before we have it available, a vaccine that is safe enough to be given to children, for example, but something will be available to prevent infection with the AIDS virus. And at that time we are going to be able to go back to a sexual revolution that was rudely interrupted.

———

EM Narration: Back in the studio, Kathleen wrapped up her report with a conversation with Joan.

———

KS: But for now, Joan, the big question appears to be, is, can there be safe sex for singles with multiple partners? Researchers at the National Institute of Health say the only safe sex is mutual masturbation. Uh, Mathilde Krim is a little bit more hopeful. She says for anal and vaginal intercourse, use a condom and a spermicide together—it offers, offers the highest degree of protection—but use them properly.

ABC News promotional photo of Kathleen Sullivan, 1986. Credit: Photo by Disney General Entertainment Content via Getty Images.

———

EM: You said the words “vaginal and anal, anal intercourse” on morning television.

———

EM Narration: I’m talking with Kathleen Sullivan, who’s on the phone from her home in Rancho Mirage, California, for a little shoptalk about that long-ago moment of blunt honesty about AIDS and sex at Good Morning America.

———

KS: And I’m surprised that they didn’t tell Joan it was coming.

EM: And what did you say to Joan about, about safe sex?

KS: Uh, uh, mutual masturbation. That’s the one where ABC just said, “We’ve gotta get rid of her,” you know. Everything I had was from Anthony Fauci.

EM: So, so did you talk to Anthony Fauci in advance of this?

KS: Tony Fauci was so important to every single reporter. Tony Fauci was there for them even privately, when they had a loved one who was sick. But Tony Fauci was there for us on every single question about AIDS, on the record and off the record. And that’s the one, the line I do remember. “Mutual masturbation” will be on my tombstone. It’s a quote from Anthony Fauci!

EM: It was very good advice. And you could certainly have plenty of fun that way. Um, although I know there were people who said that they didn’t think of that as sex. Um, and, and what, what was Joan’s reaction? Did she say anything or do you recall the look on her face?

KS: Oh, I think her lower jaw, you know, hit, hit the, hit the chair. I mean, honestly.

———

JL: Kathleen, thank you very much.

———

EM Narration: Apparently, the local TV stations that broadcast the show flipped. Kathleen thinks the segment was at least a part of the reason for her unplanned departure from ABC. When it came to talking about AIDS on morning TV, the reality and hard facts about the epidemic had to be packaged just right. Producers were always in search of a silver lining—a good news angle. Or an angle that didn’t involve talking about drug use, gay men, and sex.

And so a teenager from Indiana named Ryan White had become America’s AIDS poster child.

———

KS: Ryan, I haven’t seen you in about a year. You, you’ve lived in, uh, was it Cicero, Indiana, now for a year since moving out of Kokomo? How’s your new house, how’s the new home?

———

EM Narration: Ryan’s being interviewed by Kathleen Sullivan, who by this time is an anchor over at CBS This Morning.

———

Ryan White: It’s going really good, everything seems to be going really nice.

KS: And you’ve gained some weight, haven’t you?

RW: Yeah, I gained about 10 pounds.

KS: And how much treatment are you going through now?

RW: Well, I’m getting pentamidine twice a month and gamma globulin once a month. And I’m still on AZT.

KS: Are you exercising? Are you—you look terrific. Obviously you’re eating more.

RW: Oh, yeah. I’m eating a lot more, but I’m not really exercising.

KS: And you’re—are you that worried about getting, you know, any kind of cold or any…? I remember before, about two years ago, you were contracting colds and sore throats and had some hearing problems. Is that all better?

RW: Yeah, it’s—I’m doing really great now.

KS: That’s terrific.

———

EM Narration: Ryan White was infected with HIV in 1984, when he was 13. He was a hemophiliac, and at that time the blood products he needed weren’t yet screened for HIV. He recovered from an initial illness, but when he tried to go back to school in his hometown of Kokomo, Indiana, they told him he couldn’t, out of a mistaken belief that he was a danger to the other kids. He was bullied—blamed for getting sick, accused of being gay, told that it was “God’s punishment.”

Ryan’s family moved to a more accepting nearby community where he was able to return to school. He appeared before Congress to testify about his experiences, celebrities befriended and championed him, including Michael Jackson and Elton John. Both Ryan and his story were irresistible.

It’s early 1988, and by now I’ve followed Kathleen over to CBS This Morning, after I, too, was booted from Good Morning America. I’m waiting for Ryan and his mother to arrive at CBS’s studio on West 57th Street. It’s not the first time we’ve met: we spent time together in Indiana when I was working on a profile of him the year before. It’s really early, but he and his mother are nothing but gracious as I collect them from the lobby to usher them into makeup. One of my colleagues whispers in my ear. The makeup crew is refusing to work on him. They don’t want to touch him.

We scramble, and manage to find a makeup artist for a soap opera on the second floor who says they’ll do it. We’re getting dangerously close to air time, so we have to take the stairs. Following behind Ryan I can see he’s struggling to catch his breath. I’m enraged and embarrassed. The poster child they won’t even touch.

I’ve only been at CBS This Morning for a couple of months when the word comes down from one of the senior producers: “We’re doing too many AIDS stories.” In other words, I was doing too many AIDS stories. I was producing one a week. News coverage of AIDS had reached an all-time high in 1987. But in the years that followed, coverage actually shrank. Editors were worried about “saturation.” Reading the obituaries each morning, there were too many AIDS stories. By the end of 1988, another 32,000 cases were reported, with 11,000 deaths. So we should cover it less? I was pissed, but it was nonnegotiable. Only the occasional feature allowed.

If I couldn’t tell the stories I wanted to tell, to do the kind of journalism I valued as a producer, I wanted to do something else. I wanted to be on the other side of the camera, to be a correspondent. I’d been secretly working on a demo reel in my spare time, and coworkers who’d seen it encouraged me to go for it.

I managed to get an appointment with a CBS executive who made those decisions. If you don’t ask, you don’t get—but I was pretty sure I knew the answer. At that time, there were no openly gay on-camera correspondents on any national TV or cable news network. I asked the question what felt like seven different ways. Finally, the executive gave me her answer: no, CBS would not put an openly gay correspondent on their air. Door closed.

What is it they say about doors closing and windows opening? I got a call from an editor at Harper & Row about a book he hoped I might write. An oral history about the gay rights movement. He liked how I’d done the interviews in The Male Couple’s Guide, wanted someone fresh to the subject—could I write a proposal.

CBS didn’t want me because of who I was, at least not where people could see me. Harper & Row wanted me because of exactly who I was. Valued the part of me that I’d struggled to accept and embrace. Wanted me to excavate the history of a movement that’d made it possible for me to have a partner, to be out to my family, and to have a job where I could be out, even if I was the only one and behind the scenes. I took a leap, left CBS, and spent the summer writing a proposal. There was no guarantee I’d get a contract, but I was confident that if I did a good job it’d be accepted. My biggest worry wasn’t whether I knew how to write this book. I was afraid of getting sick and dying before I could finish it.

Barry and I still hadn’t been tested for HIV. We’d decided when the test first became available back in 1985 we wouldn’t get tested until there was an effective treatment, a bit of hope instead of an unqualified death sentence. Here’s U.S. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop addressing the National Press Club again.

———

CEK: It’s our hope that we will have a safe and effective AIDS vaccine generally available sometime toward the end of the century—say the late 1990s. And that’s about as optimistic as we can reasonably be. I hope you carry this information back to the people who write the headlines over your stories. They are frequently overstated and at variance with the facts presented in the stories themselves.

But I want to say how much I appreciate what you have done thus far to bring to the people of this country the terrible problem that they are faced with AIDS. I think you’ve done a really magnificent job. But we’re facing the same situation in regard to drugs. The only one we have now, AZT, provides some relief and even a few more months, maybe years, of life for AIDS patients with pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, but AZT does not cure anyone of AIDS itself.

———

EM Narration: In October, the latest edition of Scientific American landed in our mailbox. It was a single-topic issue on AIDS. One of the articles was a study about AZT. I already knew about AZT. David’s partner, Lou, was on it. Our friend Mark was given the chance to be in a clinical trial, but his father, who was a doctor, advised him against it because the drug could kill you. Half the people put on AZT had to stop taking it because of severe anemia. Until I read that issue of Scientific American, the benefit of AZT was still unclear. But there was the study, in black and white, that said this drug bought time. It was enough for me. So Barry and I made an appointment to get tested on November 9, three days before my 30th birthday. Next time.

Postscript. Ryan White died shortly before his high school graduation, on April 8, 1990. He was 18 years old. His death was the lead story for virtually every national and local news outlet. More than 1,500 people attended his funeral, including First Lady Barbara Bush and Michael Jackson. The New York Times reported that singer Elton John, who had maintained a bedside vigil during Ryan’s final week, led the congregation in singing a hymn, then accompanied himself as he sang his own composition “Skyline Pigeon.”

The Ryan White Care Act, the largest federally funded program for people living with HIV/AIDS, was signed into law four months later by then president George H.W. Bush. Even in the moment, it seemed more than a little bizarre that the program was named for a white teenager from a small town in Indiana when AIDS disproportionately killed gay men, Black women, and IV drug users in the nation’s biggest cities. But if not for Ryan and the poster child role he heroically embraced, it’s hard to imagine that Congress and the president would have had the courage to fight the AIDS-phobia and anti-gay headwinds and indifference that had kept the government from providing the desperately needed funds.

Grandma May very quickly adjusted to the fact I was gay. In 1992, after reading the original Making Gay History book from cover to cover, she said, “Now I understand, gay people just want to love and be loved like everyone else.” Not only had the truth about my life not killed my grandmother, she became my biggest champion. Grandma May lived to 102 and died in June 2005. On the way home from her funeral, we got stuck in traffic trying to drive across Manhattan during the city’s annual Gay Pride March. I think of her every day.

———

Many thanks to our hard-working crew at Making Gay History, including story editor Sara Burningham, assistant producer and sound designer Rae Kantrowitz, deputy director Inge De Taeye, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter. This season was recorded at CDM Sound Studios. Thanks, as well, to our interviewer-slash-oral historian Shane O’Neill and our listening circle, including Syd Baloue, Cheryl Furjanic, Dr. Jamila Humphrie, Barney Karpfinger, Ann Northrop, Benjamin Riskin, Jenna Weiss-Berman, and Mike Winerip.

Thanks also to Kathleen Sullivan and my sister, Heidi Katz, for sharing their memories.

Thank you to CBS News for use of their archival tape from CBS This Morning and C-SPAN for the recording of Dr. C. Everett Koop at the National Press Club. Good Morning America footage is courtesy of ABC News VideoSource.

Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers, with additional scoring by Rae Kantrowitz.

This season of the podcast was made possible by the generous support of the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, the Calamus Foundation, the Kipper Family Foundation, Christopher Street Financial, Andra and Irwin Press, Joel Sekuta and Christopher Williams, Bill Kux, Louis Bradbury, Jeff Soref, Kathy Danser—Daltin’s mom—and scores of other individual supporters.

“Coming of Age During the AIDS Crisis” is a production of Making Gay History.

I’m Eric Marcus. So long, until next time.

###