Christopher Isherwood

Christopher Isherwood, 1937. Credit: Howard Coster/© National Portrait Gallery, London;

Free Creative Commons.

Christopher Isherwood, 1937. Credit: Howard Coster/© National Portrait Gallery, London;

Free Creative Commons.Episode Notes

Author Christopher Isherwood left England for Germany in 1929. His stories about his years there inspired the musical Cabaret, which shaped the image of decadent interwar Berlin in the popular imagination. But as he told Studs Terkel in this 1977 interview, to him, Berlin meant, above all, boys.

Episode first published October 1, 2020.

———

Read a short biography of Christopher Isherwood here. For a book-length biography, check out Peter Parker’s Isherwood: A Life Revealed. Watch the author talk about his life and work in this short collection of filmed interviews, spanning nearly four decades, and this 1974 interview.

Find an overview of all of Isherwood’s published works here. Hear him read from his work on the album Christopher Isherwood Reads…, which he recorded when he was 71 years old, or listen to a recording of a live reading of his work here, starting at 3:44.

Isherwood and W. H. Auden had an epic, life-long friendship—the kind people write books about. As young men they explored gay life in early 1930s Berlin and wrote three plays together: The Dog Beneath the Skin (1935), The Ascent of F6 (1936), and On the Frontier (1938). They also collaborated on a book of travel writings called Journey to a War (1939). Isherwood and Auden were part of a circle of modernist British writers that included their close friend Stephen Spender.

Isherwood first found literary fame with his semi-autobiographical novels Mr. Norris Changes Trains (1935) and Goodbye to Berlin (1939). The latter inspired the play I Am a Camera (1951) and the stage musical and film Cabaret (starring Liza Minnelli).

In 1976, Isherwood published Christopher and His Kind, a candid memoir in which he revisited his Berlin years, including the time he spent in the city’s gay bars.

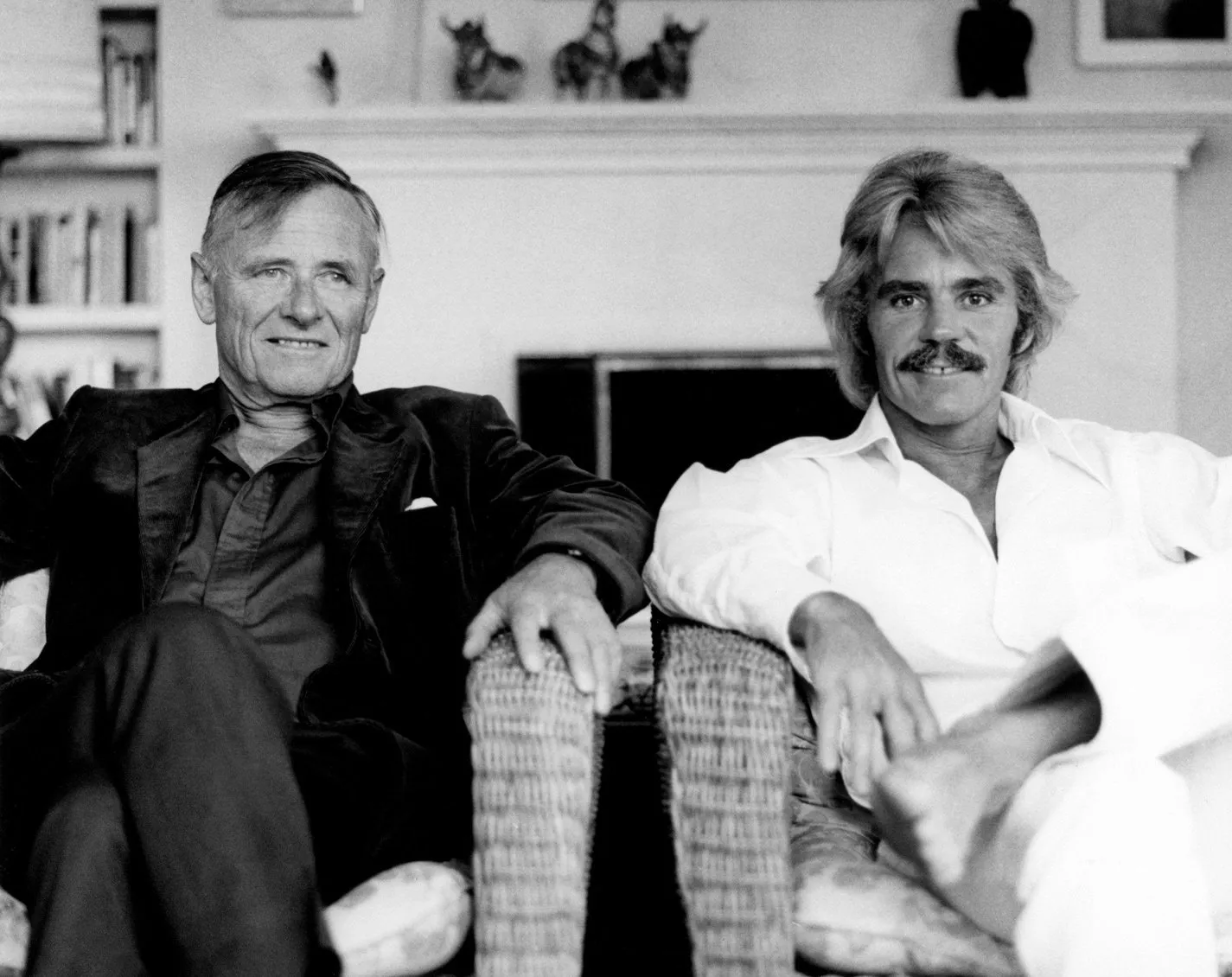

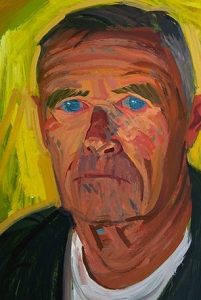

For over 30 years, Isherwood was in a relationship with Don Bachardy. For a look into their lives together, watch the 2007 documentary Chris & Don: A Love Story. Bachardy is a portrait artist; you can see some of his work here. He still lives in the house he and Isherwood shared (take a tour) and works to keep their legacy alive through the Christopher Isherwood Foundation. Bachardy sketched and painted Isherwood countless times, including right before, during, and after his death. Their three decades’ worth of love letters were published in the book The Animals, which in turn was made into a podcast with Alan Cumming and Simon Callow. See Bachardy in a virtual conversation with Eric Marcus here.

Isherwood was a prolific letter writer: read his correspondence with his mother in Kathleen and Christopher; check out Stephen Spender’s 1930s Letters to Christopher; and read Letters between Forster and Isherwood on Homosexuality and Literature for a glimpse into Isherwood’s friendship with E. M. Forster. Or go straight to the source and read Isherwood’s actual letters to his mother, brother, and editor, made available by the Beinecke Library at Yale.

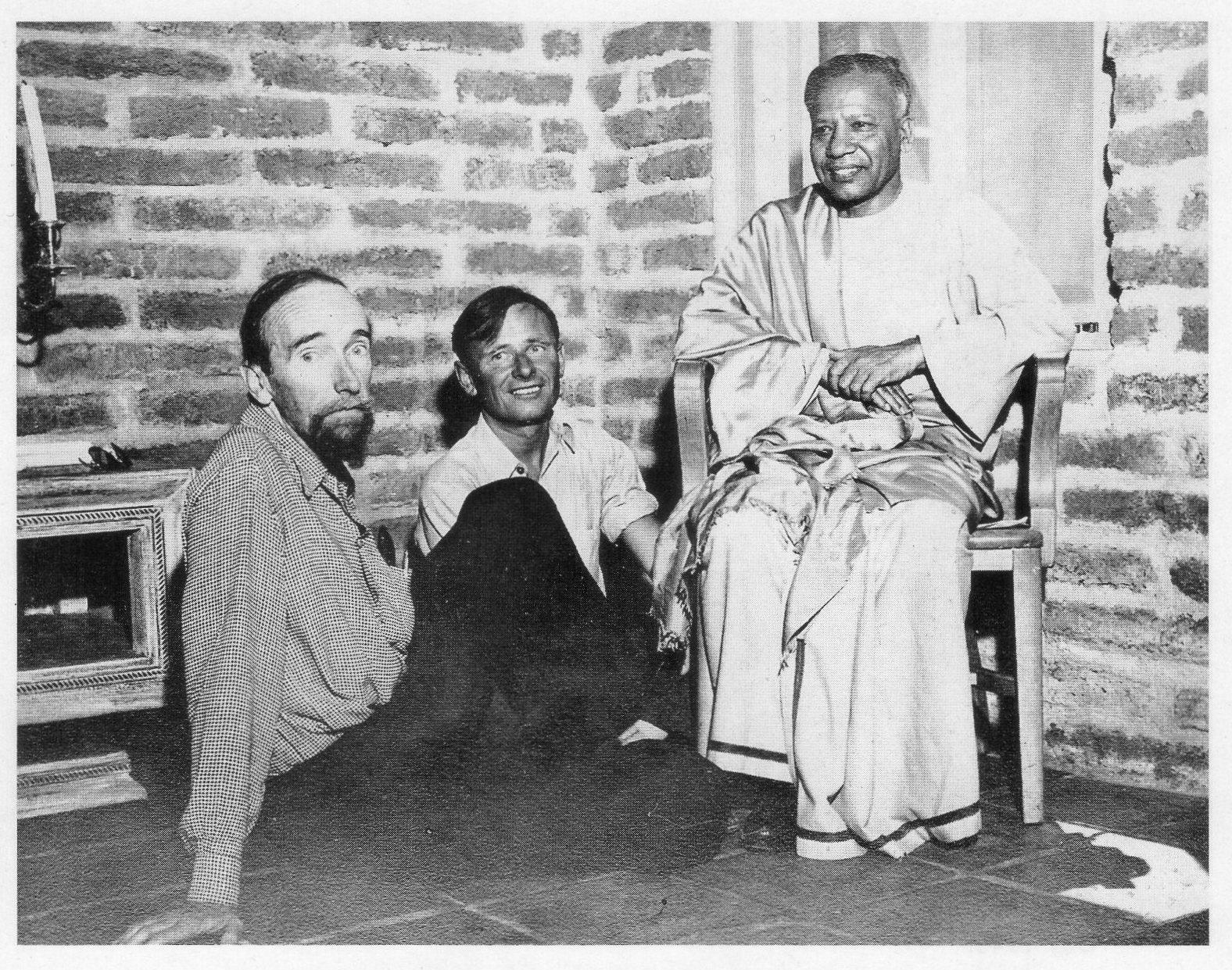

Isherwood was a follower of the Indian philosopher Swami Prabhavananda, with whom he translated the Bhagavad Gita. Isherwood also wrote a biography of Sri Ramakrishna, the founder of Prabhavananda’s spiritual order, and occasionally gave lectures about him.

After Isherwood’s death in 1986, his diaries from 1939 to 1983 were published in three volumes.

In the episode, Isherwood discusses Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld and his Institute for Sexual Research. To learn more about Hirschfeld, listen to this Making Gay History episode about his life and legacy.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus and this is Making Gay History.

This season we’re reaching beyond my own collection of interviews to bring you voices from the Studs Terkel Radio Archive. The archive holds more than 5,000 programs that the pioneering oral historian and broadcast legend recorded for WFMT radio in Chicago between 1952 and 1997.

If interwar Berlin conjures images of decadence and racy nightclubs, that’s partly Christopher Isherwood’s doing. His short novel Goodbye to Berlin inspired Cabaret, the enduring stage musical and 1972 movie adaptation. My grandmother actually took me to see the film when it first came out. She was mortified by the sexual undercurrents and what she’d exposed me to. She didn’t have to worry. I just liked the music and didn’t pick up one bit on the homosexual, bisexual, or plain old sexual storylines.

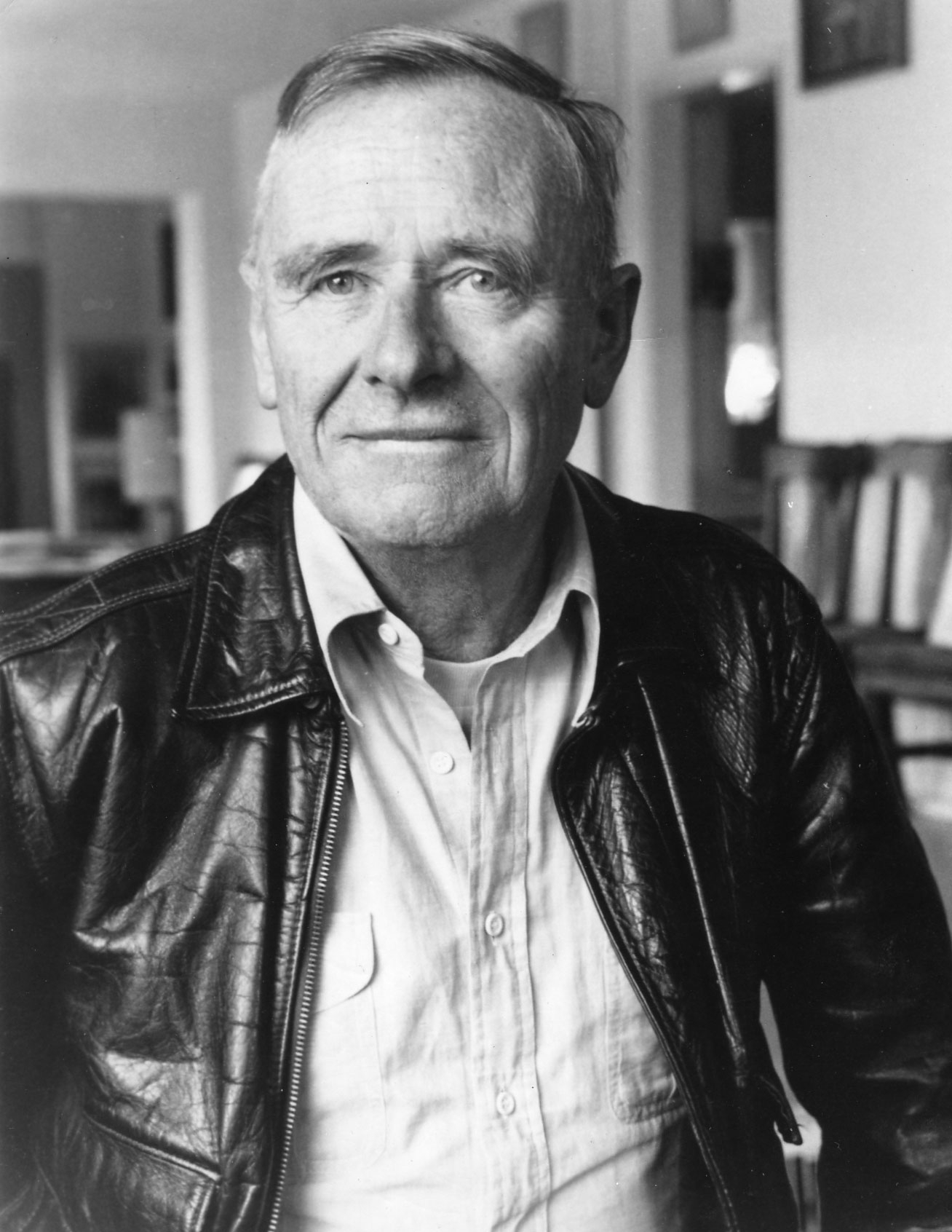

Christopher Isherwood was born in England in 1904. From an early age, he chafed at the respectability and rigid expectations of the upper middle class society in which he was raised. By his mid-twenties, he was itching for a change of scenery: his first novel had flopped and medical school, which he’d attended for all of six months, was a lousy fit. So he moved to Berlin, and spent the next three and half years of his life there. He picked up prostitutes in the city’s boy bars, slummed it with other expats, fell in love… And he wrote.

Christopher had always been out to those who knew him, but his semi-autobiographical early books about his Berlin years were vague on the subject of the narrator’s sexual orientation. In 1976, Christopher ditched the ambiguity and published Christopher and His Kind, a candid memoir about his life and work in the 1930s. And that’s the book he discussed with Studs Terkel in an interview first broadcast on February 10, 1977.

By now, Christopher is 73 years old, an American citizen, a Californian, a Hindu disciple—and, to Studs’s obvious delight, a fount of literary gossip and frank reflection. Studs begins by taking Christopher back to his days in Germany.

———

Studs Terkel: So there you are in Berlin in 1929, and the question is, what led you to Berlin in 1929?

Christopher Isherwood: Well, the immediate reason was that, um, my friend, uh, Wystan Auden, W. H. Auden, was there and wanted me to come over and visit him, and um, I was also very drawn to the idea that, uh, I was going to meet a lot of German boys there because, being homosexual, that idea appealed to me very much, and, uh, uh, I went over there and spent, uh, 10 days or so with, um, Auden.

And then, um, I began to think, well, I really would like to go back, I would like to see more. I quite fell under the spell of Berlin, and, um, so later in the year I came back on my own having made arrangements so that I could live there at least for a while, and, um, I just found out how I liked it.

ST: And also you were looking for a home. And in a way there’s a feeling here of a restlessness. You of course were wanting to write so bad, so right you could taste it, but you were looking to… not quite England, right? Not quite England.

CI: I really wanted to be on my own.

ST: On your own, yeah.

CI: And as I now realize, more than I did then, I wanted to be in another world where I could speak another language. Uh, I wanted my own language, so to speak, for myself while I was writing, but I wanted to have a, a sort of different persona, as they say nowadays. Uh, I wanted to be German Christopher instead of English Christopher.

ST: Yeah. Is this true, too, just a question: being in a different land, a different culture, you as a writer could be, know more about your home there than here—why so many went to Paris in the ’20s, that… something they realized, something about America… Is that…?

CI: Oh, that’s very true.

ST: Yeah?

CI: Yes, and also I was strongly persuaded at that time, and indeed I still believe it, that you are a different person in different places. You see, uh, you go to Berlin, suddenly you’re a German Studs and it’s very interesting to find out what the German Studs is like.

ST: Yeah…

CI: For instance, um, I was being asked, uh, just now, uh, about, uh, England and America, and I said that while I’m in England, my American half—after all, I have lived here more than half my life—comes out, but while I’m here, my English half comes out.

ST: Mm-hmm.

CI: Here I always think of myself as English, so I suppose the answer is, I think of myself as a foreigner.

ST: So wherever you may be, you’re a foreigner, and yet a foreigner yet at home. A crazy paradox.

CI: Yes, because you see, I don’t mind—

ST: Yeah, yeah.

CI: I like being a foreigner. It’s… I don’t feel, uh—I don’t understand this thing very well about roots, to tell you the truth.

ST: Yeah.

CI: I mean, I have roots, very strong roots. I’m very, very British in many ways, but I can plant, re-plant them anywhere, you know, in a moment.

ST: What’s moving me about Christopher and His Kind—which you call a revisionist autobiography—what’s very moving to me is the candor. But the, over and above that, the good humor throughout. There’s a, there’s a joy to it. Uh, that you’re free. Not that you weren’t free then—you always have been sort of a free man, but within limitations, haven’t you? Certain things you had to hide.

CI: Oh, yes, that’s true.

ST: Throughout this book we have this aspect of it, which you are so open—I suppose you might call this a liberating book, too, isn’t it, in a way…?

CI: Well, it’s liberating for those who need to be liberated. I don’t know. That depends on people. Oh, you mean liberating for me?

ST: Yeah.

CI: Oh, yes, yes. To some extent. Um, it does make a difference, that’s the funny thing. I mean, one can feel things and talk about them to one’s friends and be perfectly open about them, but actually to print them and see them going out to book shops and all sorts of people reading them, it does make a slight difference. Yes, there’s a slight sense of extra relief. There’s a sort of feeling, now, really, uh, uh, I’m absolutely—it doesn’t matter a bit. I don’t have to be, uh, the least bit cautious with anybody.

ST: Could you have done this book 10… Would you have done this 10, 15 years ago? Assuming you had the time and the energy at that time to do it?

CI: Fifteen years ago, maybe not, no. Ten years, maybe so.

ST: Yeah.

CI: I should explain to you also, there’s another thing, another thing involved there. You see, um, very, uh, very soon after my first arrival in, um, in, um, America, uh, I got to know this Hindu monk, who had a center in Los Angeles. And I became, by degrees, uh, his disciple and, um, uh, remained so ever since.

Now, as far as he was concerned, he knew all about me, including about my homosexuality, and of course the Hindus take a very different view of this. They’re not moralistic in the same sense. But he had a congregation, and um, the, uh, many of the members of the congregation brought with them their kind of Western prejudices, and they were always a little bit, uh, worried about me, uh, because from time to time rumors used to come…

ST: Mm-hmm.

CI: … uh, about me, uh, which reached their ears since I was living right there in the city. And so I did have a certain hesitation in really embarrassing him beyond a certain point.

ST: Mm-hmm.

CI: But then as time went on, this became less and less of a, of a problem, and that’s why I say that perhaps 15 years ago, quite aside from anything else, I might have hesitated.

ST: Yeah. This is one of those mysteries… How’d you come to recognize your foibles? Cause how… It’s hard for a person to recognize his own foibles.

CI: Well, you know, I was taught by masters. I mean, uh, Auden told me from morn till eve what all my peculiarities were. He was very outspoken and very candid about them. And he was always telling me that I was this or that or the other, and um, he, uh, he decided, uh, that I was infantile, but I said, uh… We both agreed really basically that, uh, people who are incapable of being silly are really not intelligent. I mean, uh, people who take themselves too seriously, who are, have sort of, um, who reach something called “maturity” or the wisdom of, uh, senior, uh, citizens or something, that’s terrible. That’s a kind of death, I think. That, that sort of, uh, um, the idea that you grow wise in some way, uh, and then, uh, can’t be silly anymore, can’t find anything funny anymore, but it’s all—you find out something called “the truth about life.”

But the truth about life is, of course, uh, just the same when you’re young, uh, and when you’re old. It’s a double-sided affair, life, and to say that it’s, uh, has to be taken seriously is just as silly as to say it has to be taken frivolously.

ST: You know, it’s beautiful, uh—not to be afraid to look like a fool. That is, not to be, not to be afraid to take risks, is what you’re… And never to lose that childlike—not childish, but childlike—wonder, sense of wonder, I suppose.

CI: Well, I wish I could say that I could maintain it. This is only a kind of aim rather than a, something that I have succeeded at. But it’s—the rigidity of not ever being childish or childlike is what is so dangerous.

ST: That’s why this book is so beautiful. It is anti-rigid and, mind, anti-pomposity, too. I found Auden’s poem about Christopher Isherwood here. Why don’t you read it? It’s about you.

CI: Yeah, this was a poem that he wrote in a book of mine and there’s, um, there’s really no other—this is just a tiny bit of it, but I, I copied it out and sent it to, uh, Auden’s literary executor. Uh, it’ll be published, I guess, one day. But this is… He was making fun of me, you see.

He says, “Who is that funny-looking young man, so squat with a top-heavy head?” He was always talking about the—my enormous head. “A cross between a cavalry major and a rather prim landlady / Sitting there sipping a cigarette? / If absolutely the whole universe fails to bow to your command, / How you scamp your bright little shoe, / How you pout, / House-proud old landlady, / At times I could shake you.”

ST: So throughout there was this, this air of, uh, self-mockery. Kidding.

CI: Oh, yeah, he…

ST: Auden, Auden had that, too.

CI: Oh, terrific. Yes, yes.

ST: We have come to something that is so much part of that time. Of course the 10 years here, in these 10 years, Christopher and His Kind, 1929 to ’39… These 10 years were, of course, traumatic and cataclysmic and overwhelming years for the world.

CI: Terrible, yes.

ST: And there you were in Germany.

CI: Yes.

ST: Now you were… Were you ever—you touch on this—politically committed to anti-fascism, say, as Spender at, at that time and Auden were, particularly when the Spanish Civil War broke out?

CI: Oh, very much so, yes. Absolutely. Uh, and, uh, also, you see, I did have a sort of special, uh—I, I mention that earlier in the book—a special kind of indoctrination, uh, as regards the, um, uh, the homosexual aspect because I, by pure accident, I, I became, uh, a boarder, uh, at this house, uh, which involved our going to have lunch every day at the institute of Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, who was the great expert on sexology and so on.

And he was a man, uh, he was himself homosexual and Jewish, uh, and also leftist inclined, and he was very, very well aware of the fact that the Nazis, even long before they came to power, said, “Germany lost the First World War because of the leftists, the Jews, and the homosexuals. These three groups undermined her morale and caused her to be defeated.”

And they were passionately on the warpath against, uh, Hirschfeld. They tried to kill him a couple of times. Once they almost succeeded. This was way, long before Hitler came into power. Because he was so daring he went and made speeches in Munich, which was their kind of, uh, headquarters and breeding ground at that time.

ST: Mm-hmm.

CI: So I did at least get through my head very early one thing: that the Nazis were bad news for me and my kind.

ST: And these are the years… Things are popping now. Oh, you also meet the German boys at these places where boys gather to be picked up, and these are mostly working-class…

CI: Uh, yes.

ST: … mostly working-class kids?

CI: Uh, it wasn’t… That was really because I had a sort of preference for them. Uh, I mean, there were lots and lots of middle class, uh, German boys who were homosexual. Um, but I, I just so happened—I always felt they were a little bit prissy. I thought they were too, sort of, dainty. They are, uh, the, what I’ve… What I liked about the German, uh, working class was as they say in, uh, in that, uh, song of, of, uh, Brecht’s, “Even his Sunday collar wasn’t white as snow.”

ST: Mm-hmm. Interesting also… You imply attraction of opposites here, too. The blonde Teutonic, and you, I guess, you were a dark-haired, young, small Englishman.

CI: Yes, there was that, too, and then of course, um, I was an upper-class Englishman.

ST: Yeah, an upper-class…

CI: And, therefore, light—I felt that the, uh, working class was forthright and, uh, and, uh, more sort of, um…

ST: This was kind of a romantic version?

CI: … less tricky somehow.

ST: Sort of a semi-romantic version, too, to some extent?

CI: Yes, yes. I, I, …

ST: At the same time you were, you were socially conscious in that respect.

CI: Oh yes. I think this feel—these feelings I would have had every bit as much if I had been heterosexual. That wouldn’t have made any difference.

ST: Yeah.

CI: I think at this period I would have been drawn strongly to working-class girls.

ST: Yeah.

CI: Uh, for exactly the same reasons.

ST: Yeah. Now there’s your mother, Kathleen. She was almost an Edwardian figure, wasn’t she? Your mother?

CI: Oh, yes, uh, very much Edwardian.

ST: When did your mother recognize your preference, that you were homosexual? Or did she ever accept it?

CI: Well, she did and she didn’t. My mother was the sort of person who, uh, was, uh, very good at kind of glossing things over. Uh, and, um, yes, she accepted it, but um, she didn’t quite, uh… She said to me once in a moment of candor, uh, she didn’t really qui—it didn’t seem real to her, because she really couldn’t imagine, uh, any kind of sexual act in which a woman wasn’t involved.

ST: Very funny.

CI: Therefore, I suppose, lesbianism would have seemed perfectly natural—doubly natural—to her.

ST: But there was one part you, about your mother, when, uh, it was a German working-class kid, your, your young friend Heinz, was it, I think? She was… Was it Heinz, or, or…?

CI: Yes.

ST: She wasn’t too crazy—she accepted it, but later on when a couple of English boys came along, upper-class ones, that was different. A matter of class was involved there.

CI: That was much nicer, yes, yes.

ST: Yeah.

CI: She liked that, yes, yes.

ST: There’s a very funny story—do you think—with the marriage, uh, the marriage of convenience between Auden and Erika Mann, Thomas Mann’s daughter.

CI: Yes.

ST: Now, she wanted to marry you. Suppose you set the scene for that.

CI: Yes, well, what happened was that she, uh, had an anti-Nazi cabaret and they used to perform in such places as Holland and Belgium, in Austria, which then was not occupied by the Nazis yet, and, um, in Switzerland and in Denmark.

And, uh, I was in, um—at the time I guess this was in Belgium, maybe Holland, I forget… And she said to me one day, “Christopher, I have something rather personal to ask you. Um, would you marry me?” And the reason was that she’d just heard that the Nazis were going to take away her citizenship. And at that time the law was that if you married a British subject, you became British instantly without any former, uh, any further formalities whatever.

And I, uh, had a couple of reasons why I didn’t want to get married. Um, one sounds really truly childish, uh, but, uh, it was curiously strong: I was terribly embarrassed at the idea that anybody would think I was trying to pass for a heterosexual by getting married. And, uh, so, um, I, um, uh, I thought, well, at least I’ll see if I can’t get somebody else. And I immediately thought of Auden, who was always very adventurous in any—anything of this sort. And he wired back: “Delighted.”

Well, they got married and that was all right, and the funny thing was that, uh, a little while later, when we get to the United States, um, we went to stay with the Manns. Uh, a Time magazine photographer came, and the Time photographer said, “I can understand why Mr. Auden is sitting in this family group, because after all, he’s your son-in-law, but what is Mr. Isherwood doing here?” And, uh, Thomas Mann answered in German, which everybody understood except the photographer. He said, “He’s the family pimp.”

ST: You were the matchmaker! You had arranged it.

Perhaps this last—before we say goodbye for now… Not that you were less politically—you never were… You are not less politically committed, but now fully committed to the idea of, in a sense, liberation of the homosexual.

CI: Yes, and in, in, in a more general way, if you asked me what my politics were, I should really say I am a member of the American Civil Liberties Union. That’s to say I am a regular kind of liberal. And I’m much more interested in local causes, uh, by and large. I mean, I’m more interested in California politics than in national politics…

ST: Yeah.

CI: … uh, insofar as I…

ST: Well, perhaps you may have the answer to a great deal of what is the dilemma today, people looking for some little triumph, some little victory, some little effect of thems—of what they do since they’re overwhelmed by other events, and maybe community victories and community matters might, in that sense, extend to the city, to the country, to the world. The little victories.

CI: Oh, yes. I know many people whose lives are absolutely, uh, enriched by doing these things.

ST: Perhaps you could read this last part. You speak of third person…

CI: Oh, yes.

ST: This last part, in a sense, might be close to your credo.

CI: “He must never again…”

ST: Yeah.

CI: “… give way to embarrassment, never deny the rights of his tribe, never apologize for its existence, never think of sacrificing himself masochistically on the altar of that false god of the totalitarians, the Greatest Good of the Greatest Number—whose priests are alone empowered to decide what ‘good’ is.”

———

EM Narration: By his own admission, Christopher Isherwood wasn’t very concerned with gay rights when he first moved to Berlin in 1929. He treated homosexuality as “a private way of life discovered by himself and a few friends.” But through his visits to Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Research he began to discover a broader kinship.

By then, it had been more than three decades since Dr. Hirschfeld had founded the Scientific Humanitarian Committee, the world’s first homosexual rights organization. As Christopher told Studs, Hirschfeld was a gay leftist Jew who became an early Nazi target. On May 10, 1933, the Nazis burned his institute’s library, along with a bust of Hirschfeld himself. Christopher was there, and looked on in quiet horror. He left Berlin a few days later.

In 1939, on the eve of World War II, Christopher and his lifelong friend W. H. Auden both emigrated to the United States. Auden settled in New York, Christopher in Los Angeles. He wrote fiction, as well as autobiographical and dramatic works, and he published translations of Hindu texts in collaboration with his spiritual teacher.

When he was in his late 40s, Christopher began a relationship with 18-year-old Don Bachardy, who became a gifted portrait painter. They remained partners for more than three decades.

Christopher Isherwood died on January 4, 1986. He was 81. Don Bachardy still lives in the Santa Monica home they once shared.

To learn more about Christopher Isherwood and to listen to our season four episode about Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, please visit makinggayhistory.com. That’s where you’ll find all our past episodes as well.

Many thanks to everyone who makes Making Gay History possible: senior producer Nahanni Rous, co-producer and deputy director Inge De Taeye, audio engineer Jeff Towne, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media team, Cristiana Peña, Nick Porter, and Denio Lourenco. Special thanks to Jenna Weiss-Berman and our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Studios, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Season eight of this podcast is produced in association with the Studs Terkel Radio Archive, which is managed by WFMT in partnership with the Chicago History Museum. A very special thank-you to Allison Schein Holmes, Director of Media Archives at WTTW/Chicago PBS and WFMT Chicago for giving us access to Studs Terkel’s treasure trove of interviews. You can find many of them at studsterkel.wfmt.com.

Making Gay History’s eighth season has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, proud Chicagoans Barbara Levy Kipper and Irwin and Andra Press, the Small Change Foundation, and our listeners, including Greg Adgate, who made a generous donation in honor of his daughter Anna. Thanks, Greg!

So long. Until next time.

###