Coming of Age During the 1970s — Chapter Two: Fire Island and Other Stories

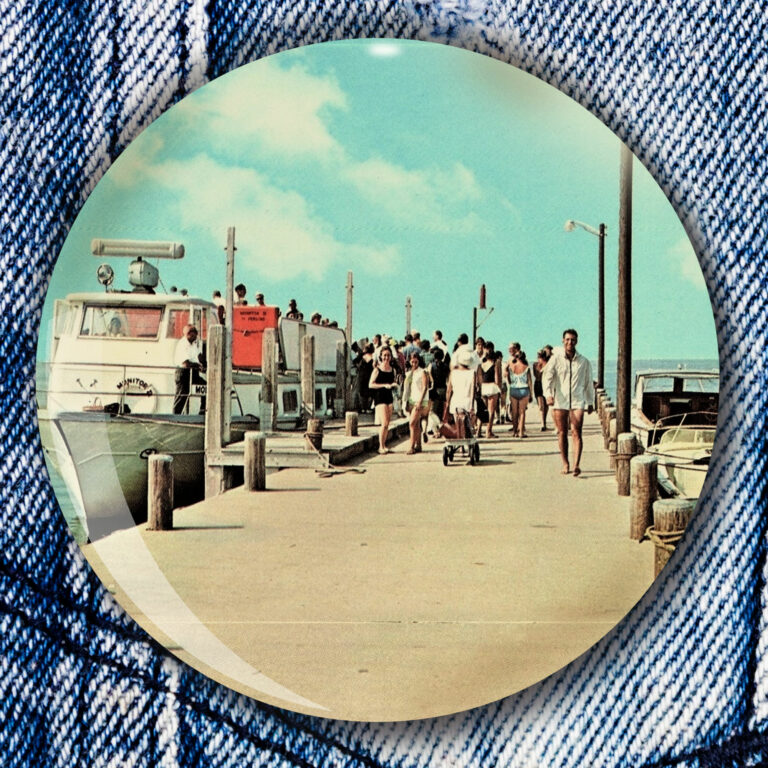

1968 postcard showing the ferry dock in Cherry Grove, Fire Island. Credit: Image via Vintage Cherry Grove NY/Facebook.

1968 postcard showing the ferry dock in Cherry Grove, Fire Island. Credit: Image via Vintage Cherry Grove NY/Facebook.Episode Notes

While activists are demonstrating, filing lawsuits, and pushing for anti-discrimination laws, 16-year-old Eric is on a ferry to Fire Island, a legendary gay refuge off Long Island, with his neighbor Rev. Mullen—a trip that would introduce him to a vivid slice of mid-1970s gay life, ready or not.

Episode first published April 27, 2023.

———

Learn more about some of the topics discussed in the episode by exploring the links below.

General resources about Fire Island:

- Cherry Grove, Fire Island: Sixty Years in America’s FIrst Gay and Lesbian Town, by Esther Newton (Duke University Press, 2014).

- “The Fable of Fire Island” by Clark Polak (Drum, November 9, 1965).

- “Cherry Grove Stays Aloof from Gay Activists’ Cause” by Tom Buckley (New York Times, July 14, 1972).

- “Hidden in a Fire Island House, the Soundtrack of Love and Loss” by T.M. Brown (New York Times, April 29, 2022).

- “The Very Gay History of Fire Island,” the Bowery Boys podcast (2021).

- Local preservation organizations: Fire Island Pines Historical Preservation Society (FIPHPS), Cherry Grove Archives Collection (CGAC).

Fire Island: locations, traditions, ambience:

- History of Cherry Grove: collection of short films with archival footage and commentary (CGAC); interview with Michael Fisher, director of the documentary Cherry Grove Stories (2018).

- History of the Meat Rack (FIPHPS).

- History of the Tea Dance (FIPHPS).

- “Invasion of the Pines” tradition (est. 1976): historical overview (FIPHPS); The Panzi Invasion, a documentary by Parker Sargent (2019).

- Mid-1970s footage of Fire Island (Nelson Sullivan/YouTube).

- The 1970s party scene (FIPHPS).

International Male catalog:

- “How One Mail-Order Catalog Changed Men’s Fashion—and Queer Desire—Forever” by Nathan Tavares (GQ, June 1, 2021).

- ALL MAN: The International Male Story, a documentary by Bryan Darling and Jesse Finley Reed (2022); trailer here.

A Very Natural Thing film:

———

Episode Transcript

This episode of Making Gay History contains adult content and strong language. It is not appropriate for children or for class use below the college level.

———

Eric Marcus Narration: Shane O’Neill is interviewing me again. He’s a journalist at the New York Times, and a friend. We worked on the “Coming of Age during the AIDS Crisis” season together, and he’s once again turning the tables: he’s asking me the questions, recording my oral history. We’re on Zoom, and this time he’s taking me back to my mid-teens. Shane’s asking me about my life in the new neighborhood we’d moved to in 1974—Jamaica Estates, Queens.

It’s almost four years since my father killed himself. My mother used the money that came to her after the deaths of my father and her mother to buy a house. A house! A skinny three-story Tudor Revival on a narrow lot on a leafy street in a fancy neighborhood that’s just two stops on the subway from my old neighborhood. It’s a far cry from the one-bedroom apartment we left behind.

———

Eric Marcus: Not long after we moved in, there was a, a knock at our front door. And I saw this sort of smiling, Midwestern face with glasses, in a tie and a camel-hair coat. And I opened the door, and this man, who must have been then about 40-something, introduced himself as our neighbor. Uh, the Reverend Mullen. And I soon learned that he was a widower. My mother was a widow, and I had thoughts of Rev. Mullen and my mother living happily ever after. He was well-dressed and he was smart, so—and he had a beautiful house that was, like, three times the size of ours.

Shane O’Neill: So you, he shows up at your door. You’re like, maybe my mom can have a boyfriend. Did that work out?

EM: No, uh, no. Not even close, because he was much more interested in me than he was my mother. Um, but the interest he took in me, uh, uh, was that of an older person… Um, I don’t know if I thought of him as a father figure, but I certainly was a boy in search of that kind of person in my life. And he recognized me as somebody who might need that. And I’m guessing he spotted early on that I was probably a gay kid. Uh, and he took an interest in me.

He, probably not long after that, invited me to go to the Harvard-Yale game with him, and to see Yale University. I was at that point looking at colleges. I come from a working-class background. Harvard, Yale, … I mean, it’s a, a whole other world. I had never been to those places.

Um, after my father and mother split, I spent every other Saturday with my dad, and we might go to Connecticut to visit friends of his or Long Island to visit my aunt and uncle. And then when he, after he killed himself, that was like my world came to an end, and I would sit by the window on Saturdays and watch and hope that he’d come back. Yeah, and he wasn’t coming back.

So to have an adult who was worldly and asked questions and invited me to go someplace, um, I was, I, I was so happy to do it. And I liked him. He was smart.

But I remember being at Yale and going by the gym, this magnificent gym, and he told me how when he was at Divinity School, they would swim in the pool naked. So there were various, uh, ways in which he brought things up in a probing way that I, you know, I didn’t realize what was going on.

SO: Um, so, first of all, I guess I would, I would, I would start this just by saying, obviously I think we’re gonna be talking about kind of a sensitive story for you. So, like, please, if you don’t want to remember something or dive into something, obviously, Eric, I hope you would know that you can say, “I don’t wanna talk about that,” or redirect it in a way that, that you feel comfortable with.

EM: There is nothing that I would redirect.

SO: Okay, great.

EM: What’s interesting to me is that, that it still makes me uncomfortable…

———

Vito Russo: No, Mary, we’re going to Fire Island… We’re going to Fire Island…

———

EM Narration: I’m Eric Marcus. This is “Coming of Age During the 1970s,” a production of Making Gay History. Chapter two: “Fire Island and Other Stories.”

———

Tom Buckley Voice-over: From the New York Times, July 14, 1972: “Homosexuals may be offering resolutions at the Democratic National Convention, demonstrating at city halls and state houses all across the country, and going into court to demand equal treatment under the law, but here, on the seacoast of Bohemia, no sound fiercer than the shrieks of the circling gulls is to be heard. ‘We don’t need gay liberation,’ said the head of the decorating staff at a New York department store, expressing a commonly held view. ‘We have always been liberated out here in the Grove.’”

———

EM Narration: July 1975. My first time on Fire Island. At a house in Cherry Grove. It belongs to a friend of Rev. Frank Mullen. I’m 16 years old. And I’m watching a naked man vacuum an orange shag rug.

Even 50 years later, the story I’m about to share with you feels like a betrayal. It feels like a betrayal on a couple of levels. First, on a personal level, it feels like a betrayal of a person who I still think of from time to time—who introduced me to a broader world, who introduced me to my first love, and who helped me understand my identity as a gay man. It was one of the most consequential relationships of my young life, with a man who gave a lot of himself to a lot of people, who was not out in his lifetime—whatever “out” might have meant to him.

Second, it feels like something of a betrayal of my community—us LGBTQ folks—to say anything that could add fuel to the fire of the bigots who call us groomers, and worse. I feel protective of our elders, those who went before me through times much harder, scarier, and more dangerous than when I grew up in the 1970s. For newer generations, those experiences, those realities, are, thank god, almost unimaginable.

But I’m telling this story because it’s a part of my coming-of-age story—more than that, it’s central to it. And I’m telling it because our stories are complicated, and life is nuanced, and I trust that we—you and I—can hold this space together. And the bigots? They can go fuck themselves.

The bay between Sayville and Fire Island’s Cherry Grove is smooth as glass. It’s Saturday morning on a sunny and warm mid-July day in 1975, and I’m on a ferry boat with my neighbor, Rev. Frank, heading to a sliver of a barrier island 20 minutes from the mainland. He invited me to go with him for a beach day to a place that’s only about an hour and 15 minutes east of where we live in Queens. But it’s all new territory for me.

Rev. Frank tells me there are no cars where we’re going—just boardwalks and small houses. He also tells me there might be some gay people. At 16, I had never knowingly met any gay people. How would I? There are no GSA groups for teens. PFLAG is still in its infancy. And being out in high school is so beyond the realm of possibility that it’s not even imaginable.

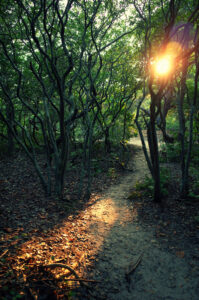

Our first stop is a visit with a friend of Rev. Frank’s who has a small house a short walk from the ferry landing. There’s a magical, hidden-in-the-woods feeling to the place as we turn off the main walkway onto a side path bordered by high, scrubby shrubs and trees. And then we turn again onto a little raised boardwalk that leads to an open front door of a one-story wood-sided cottage.

Rev. Frank walks in ahead of me, says “Hello” to the guy in the living room, and continues through to the back deck through an open sliding glass door.

I follow him, but I stop in my tracks at the entrance to the living room. There is a very tall, very handsome muscular man with dirty blond curly hair, and a huge penis, vacuuming the burnt orange shag area rug. He is completely naked except for sandals. He looks at me, sees me looking at his you-know-what, smiles, and goes right back to his vacuuming, and it goes back to swinging this way and that, as the vacuum cleaner rhythmically glides back and forth on the rug.

This is not like any penis I’ve ever seen. Not that I’ve seen a lot. Almost all of them have belonged to the boys at Jewish summer camp. I’ve never seen an uncircumcised penis before. I’m guessing that that’s what I’m looking at. I can feel myself turning bright red. Almost as red as the vacuum man’s sunburnt behind, which has also grabbed my attention. I’m mortified.

———

EM: And I said “Hello,” and then I walked out onto the deck, and there were two of Frank’s friends, one of whom was a large man in a kaftan with a big gold amulet around his neck. And that was, that was how the visit started.

SO: Was there any mention about why this person was vacuuming naked?

EM: No. And I didn’t think to say, “Why is there a naked man…?” In my memory—’cause I’ve gone over this memory many times—I think he has probably grown from five-ten to six-six, um, in my head…

SO: To say nothing of how the foreskin has grown in your memory.

EM: Right. Uh, it was memorable. Nobody discussed it, and I didn’t ask any questions. Um, but at the table, you know, there was, there was chitchat about what was going on, you know, what we were doing there. And Frank described, you know, what the day was: we were gonna have a walk over to the Pines… And, and one of the guys, one of the two men, said, um, “Be careful, uh, uh, in the Meat Rack. You could get raped.”

So I didn’t know what a “meat rack” was, and I didn’t know what, what he meant by getting raped because how could a man be raped? So he explained what the Meat Rack was—this area of shrubbery between the two towns where guys would go to have sex.

I mean, I think about it now… I was a young teenager and they must have seen the expression on my face. I’d never heard of anything like this before. And then I asked, “How could a man be raped?” And they described how a man would rape a man.

As soon as I got Rev. Frank alone, I said, “We’re leaving, we are going home,” because I was really upset at that point. And he persuaded me to, to stay—that there was something called Tea Dance in the afternoon, we would walk along the beach to the Pines, we would not go through the Meat Rack…

And so I stayed. And we went to Tea Dance. There was also a disco next to the deck where there—and I didn’t drink, I was way too young…

SO: Says you.

EM: Says me is right! I didn’t have my first drink until I was 18.

SO: Yeah.

EM: Shane, I was such a straight-laced kid. I was the Andy Tobias “Best Little Boy in the World.” I didn’t take drugs, I didn’t smoke, I didn’t have sex. I was like, I never broke curfew. There was never any danger of, of curfew because I didn’t go out.

So there was a, a sort of disco place—uh, I think it may have been the Monster or something else. And we went in and there were two guys kissing on the dance floor. It was almost all men. And Frank said, “Aren’t you gonna ask someone to dance?” I was like, “No.” Um, and then I spotted the one—at least it was one girl in cutoff jean shorts and a T-shirt and close-cropped hair… And I asked her to dance, and she looked at me like I was nuts. We did not dance.

Um, uh, and we went home and I didn’t tell my—my mother said, you know, “How was it?” I said, “Oh, you know, it was a nice day at the beach.” Didn’t tell her a thing.

———

EM Narration: My lips were sealed. I didn’t tell my mom anything about that day. Walking along the beach to the Pines. The naked man vacuuming. The teasing about rape and the Meat Rack. How scared I’d been. How repelled and intrigued and confused. I didn’t tell her. Didn’t tell anyone for the longest time, because there was no one to tell. Who? I wasn’t out. Not even really out yet to myself.

But this was such a significant day in my life. It was the first time ever I had been in a gay space. It was the first time ever I knowingly met other gay people. Over the years, conducting interviews for Making Gay History, I’ve lost count of the people who told me about how their first times in gay spaces felt like coming home. That they had found home. All I wanted to do that day was go home. Run away. Pretend it never happened.

And it could have been so different. Fire Island didn’t have to be terrifying. It is a cherished and almost sacred site for LGBTQ people. And you know what? I still haven’t been to the Meat Rack. And it wouldn’t feel right to visit Fire Island without taking a peek…

David Boyer is an oral historian and producer who started researching the Meat Rack 10 years ago. He’s gonna take us on a tour through that scrubby brushland between the Pines and the Grove and its rich, but largely uncovered history.

———

David Boyer: So I am heading into the Meat Rack on what is supposed to be the busiest time, which is a Saturday as the sun is beginning to go down. And we are heading in from the bayside, and to my left are a couple of swans. I love this place.

———

David Boyer Narration: For a hundred years, amidst acres and acres of pine trees, with waves crashing in the distance, men have been having sex here, myself included. This is a public space made private by hidden nooks and a network of narrow paths that weave through the scrub and sandy-floored forest. Wearing old school over-the-ear headphones, pointing a mic in the air, into the bushes, down at my feet, I am a strange sight, even for the Meat Rack.

———

David Samuel Menkes: What are you listening for?

DB: I’m doing an audio interview history of the Meat Rack… What?

DSM: I don’t know, should I talk or not?

DB: Up to you.

DSM: What are you…?

DB: By the way, we don’t have to use your name.

DSM: I don’t care. I’m a rather public figure.

DB: Oh, good. Even better. What’s your name?

DSM: Hi, I’m David Samuel Menkes.

———

DB Narration: As luck should have it, I have bumped into one of a handful of unofficial mayors of the Meat Rack, which is also known as Judy Garland Memorial Park and the Enchanted Forest.

———

DSM: I kind of take care of this forest. I’ve been doing so since 1982 or ’83, making sure the paths are clean and… Would you like to go on a tour?

DB: Yeah. Come on now.

DSM: Right now we’re in, we are in the low forest, the cedar grove, and up there, that’s Cocksucker Hill, and that’s Cocksucker Hill Two. And that’s the Main Rack. Then there’s the Lower Rack, just on the other side of the hill, and then there’s the Ballroom.

DB: What are you doing?

DSM: Picking garbage out of the trees, what does it look like? I try not to think badly of people ’cause this is the heat of the moment and…

DB: What’s in your hand?

DSM: Condom wrappers. Thank god they’re using them, I suppose.

DB: So how do you feel about the history of the Meat Rack being told?

DSM: I think the Meat Rack fulfilled a certain function for a certain group of guys. And whether it’s doing that still or not, it still has that history. It’s like any, any place. Like Alexander Hamilton’s homestead: “This happened here.”

DB: What happened here?

DSM: People had sex here without fear.

———

DB Narration: At least since the 1920s. That’s when Long Island Railroad began shuttling city dwellers on steam-powered passenger trains. Carl Luss, a Cherry Grove historian who helped get the town’s theater on the National Registry of Historic Places, explains that, from the beginning, the Grove attracted New Yorkers in the arts and culture looking for a private getaway.

———

Carl Luss: These people began to talk and they would say, “By the way, did you know that there’s this wonderful place, you know, 50 miles away from here, where, you know, you can go and be yourselves?”

———

DB Narration: By the time painter Jack Dowling arrived in Cherry Grove in the early 1950s, the town was an established artist enclave, and some of the biggest names in theater, literature, and fine arts summered here.

———

Jack Dowling: The Meat Rack didn’t grow into what it famously became until later. It wasn’t like that in the ’50s because, to start with, the Pines did not exist. Uh, so the dunes between here and where now the Pines were enormous. And there was a little fishing shack up in those dunes that I, I used to go up into, and it was really high. Um, it was a great cruising spot.

———

DB Narration: From this vantage point, Jack could see the action on the beach in front of him and in the woods behind him.

———

DB: Was it called the Meat Rack? When do you…?

JD: No.

DB: What was it called back then?

JD: It wasn’t called anything because it was just open land.

———

DB Narration: By the ’60s, that open land had become the Pines, a thriving, mostly gay resort community with a harbor, a hotel, a yacht club, and upwards of 100 homes. Men from the Grove made their way through the forest to go dancing at the Sandpiper in the Pines, and the guys from the Pines marched en masse to the Grove’s Ice Palace.

———

JD: And I think that’s when and how the Meat Rack developed. Uh, the interchange between the two communities. So there was the path through the area that we now call the Meat Rack. And so people might go off that walk for a little, uh, business. But there weren’t all the paths there are today. Today it’s like a spider web of paths.

———

DB Narration: Dominic DeSantis arrived in the Grove in the late 1950s, finding a paradise of openness and acceptance. But the harsh realities of rampant homophobia cast a shadow from the mainland that stretched all the way to this haven across the Great South Bay.

———

Dominic DeSantis: You never gave your full name; you only gave your first name or your camp name. There was Terry, Susie, … We never knew their real names unless you got real close to them, but a lot of people, we only knew them by that name.

DB: Why do you think?

DD: Because once they got back to the mainland, they had to revert back and they didn’t want anything spilling over there to ruin their—uh, they couldn’t come out of the closet, as they say.

DB: Like, if you were in the Meat Rack, would people be using camp…?

DD: No! No, no. You never talked in the Meat Rack. You could puff out a cigarette and the end of the cigarette lit, you could see where people were. Because it got dark out, down there, as you probably know already.

DB: I do. Did you go to the Meat Rack or did everyone go to the Meat Rack?

DD: Everybody went to the Meat Rack.

———

DB Narration: By the late ’60s, if you were gay and living in or near a big city, you probably heard whispers of a magical place called Cherry Grove on Fire Island. Bob Whiteman read about it in a dime store novel, which sent him on a quest to see it in person.

———

Bob Whiteman: I did find out that there was a ferry from Sayville, and, well, it was very exciting coming across because it was first of all packed—packed with men. Yeah, this is, this really is where I want to go. So I get off the ferry and I kind of, you know, meander toward the ocean, and I get out to the ocean, and I was a terrified 16-year-old out on the beach. So I put my blanket out and I lay there, and I got a terrible sunburn my first time. And, um, I just took it all in. I just took it all in.

DB: What were you taking in?

BW: Well, just the frolicking about the beach. I, I, I think that people came here to frolic because they didn’t have an outlet. They didn’t have an opportunity to be themselves at that point in time. I mean, everything was undercover, you know, and, you know, we were outlaws, we were psychiatric… And I think here they could, they could be themselves.

At that point there were no signs, “Keep off the dunes,” and people really did always walk up into the dunes and cross over into the Meat Rack. And people would be climbing up and sliding down and playing in the dunes. And, um, where the driftwood had accumulated, they had built these little beachside enclosures that they called cribs, where men were having all kinds of sex.

Basically, they built them so that they could be recessed into the, into the dune and open to the ocean, and a guy could be standing there and watching for the police coming by. The cops used to go into the Meat Rack and, um, arrest people and they would, uh, bring them and they would actually handcuff them at the dock, and they’d get a boatload—I’m not kidding you—um, like, prisoners. And they’d, um, bring ’em back to the mainland.

———

DB Narration: And after the men were booked, the police would routinely release their names, addresses, and professions to the press, outing them and often ruining their careers and their lives. This practice began in the late 1930s and only ended in 1968, after 17 men successfully fought the charges in court with the help of the Mattachine Society. This was an early victory for the gay community, just a year before Stonewall.

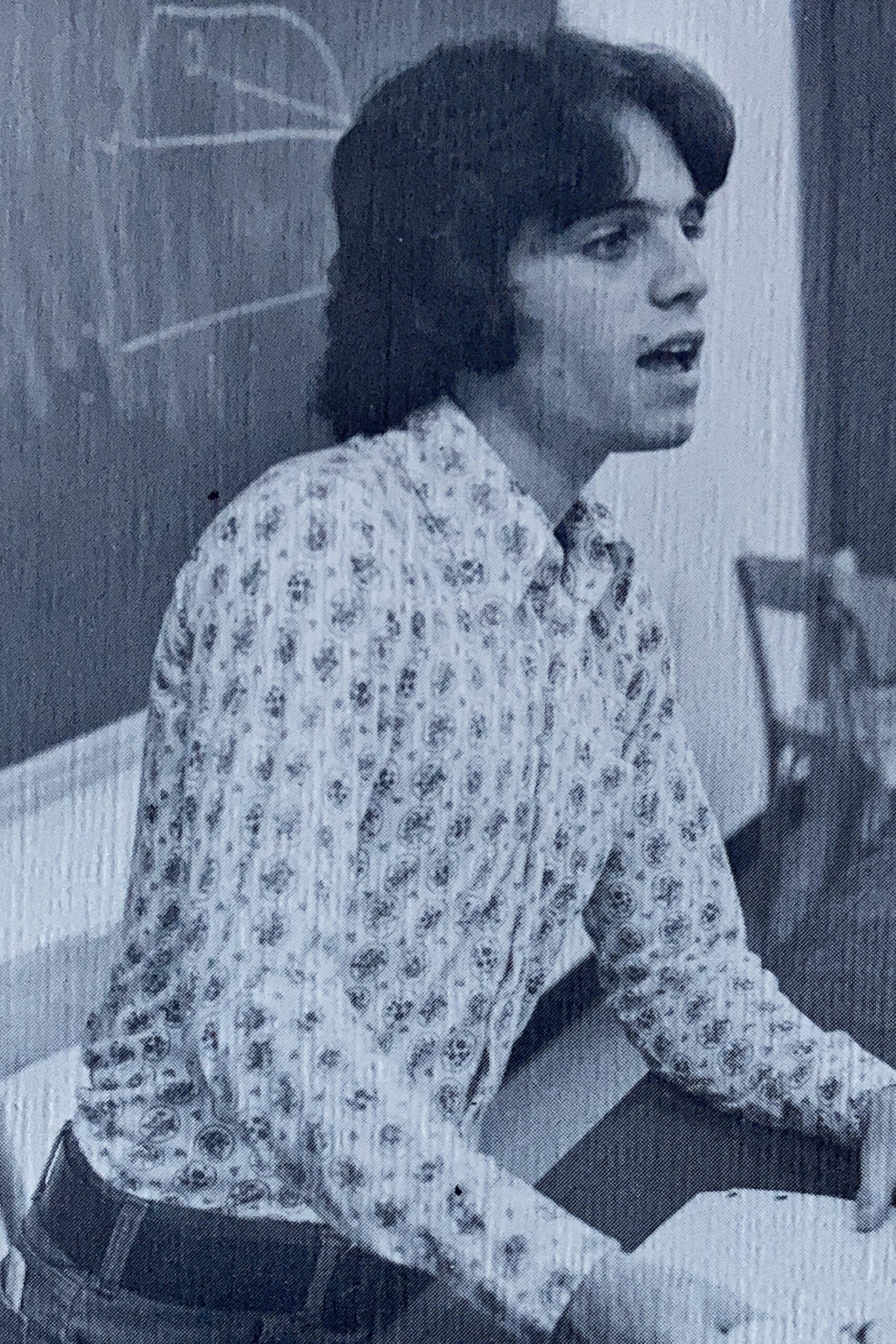

So we arrive at the ’70s. Gay liberation had become entwined with sexual liberation, and when Eric came to Fire Island for the first time in 1975, the Meat Rack was at its zenith. I can only imagine how 16-year-old Eric, looking like a cross between Greg Brady and the oldest Partridge brother, might have been received by the crowds in the Meat Rack.

One longtime Grove visitor who prefers to remain anonymous struggles to find the words to describe the epic-ness of the Meat Rack in the mid ’70s.

———

Grove Visitor: In those pre-AIDS days, it was really something to see. Um, the Meat Rack wasn’t just, you know, one little adventure here and there. It was, like, a huge, uh, uh, how would you call it? Fuckodrome.

DB: Fuckodrome.

Grove Visitor: With, uh, something like, like, uh, thousands of people at times, you know, on Saturday nights. During the night, it was, like, everywhere.

DB: Wow.

Grove Visitor: Just everywhere. It was just, it was crazy and fun.

DB: Yeah.

———

DB Narration: A busy night these days is a dozen guys looking to get off. But back in the mid-’70s, it was so fashionable and frequented that many scenes were going on at any given time. Tony Bondi describes a place that was about more than sex. It was a party, with candelabras hanging from trees and full-on dinner parties.

———

Tony Bondi: People on the weekend used to go to the Rack between 2:00 a.m. and 6:00 a.m. That’s when everybody left, when the sun came up. You used to meet your friends in there, have conversations. Some people would bring champagne and they’d light candles. It was a whole happening, you know? It was something everybody did.

DB: Now?

TB: Now? No, no. I haven’t been there in 15 years. I’m too old for it now. Did it, done it, been there, done that.

———

EM Narration: Well, I didn’t do it, wasn’t there. Didn’t want to. And I am definitely too old for it now. And too married. But thank you, David Boyer, for that immersive tour of what I so narrowly missed.

But now let’s get back to my conversation with Shane O’Neill, and back to sorting through the memories and questions I have from my life in the mid-1970s, especially after that trip to Fire Island with Rev. Mullen.

———

SO: Hearing this story, I’m of several minds. On the, the one hand, you know, as someone who’s also fascinated by gay history, I’m just thirsty for these details and curious about what Fire Island was like in the ’70s, so that’s interesting to me.

I also feel massively protective of you and, like, upset on your behalf that you would be put in this situation that’s so uncomfortable and so potentially dangerous. And as someone who cares about you, it hurts me to hear you say, like, “I want to go home,” and to hear someone who has control over you be like, “No, I’m not, we’re not doing what you want,” is very scary and sad.

By the same token, I also—and I’m, I don’t know if this is, like, a defense mechanism or what—but there’s a part of me that is almost immediately saying like, well, it was the ’70s. It was a different time. You didn’t have the Internet. These days a 16-year-old boy would have more context. They didn’t know what they were doing…

There’s a part of me that feels like, for some reason I’m almost bending over backwards, even though I’m angry and sad and worried on your behalf, that I’m also somehow, like, excusing this from a historical context. What’s your take on how history plays into this, or what the time was like then versus now?

EM: I did and do exactly as you have said. I excuse men of that generation because of the world in which they grew up. It was a very different time. The men who were then in their 40s, they would’ve come of age long before, uh, gay life was anything recognizable to us. Yeah, I excuse them, and I blame myself for not knowing better and putting myself in that situation, um, of course without knowing what I was putting myself into.

So yes, I excuse them. But on the other hand, these guys were in their 40s or early 50s, and they should have known better that their behavior was potentially harmful. But that’s not how they approached it, um, at all.

———

EM Narration: That wasn’t how Rev. Mullen approached it, and for years I’ve wondered about why. What was he thinking? Perhaps he was thinking that I was a young gay guy, and it was his responsibility to introduce me to the culture, to bring me out. Maybe he recognized himself in me? Maybe that was why his exposing me to this stuff was creepy to me but apparently not creepy to him. Maybe he assumed I did know what Fire Island was and my going along was a kind of consent. I don’t know what he was thinking because he never told me. During the two years when we were close—or what I thought of as close—we talked for hours and hours and hours, and he asked me all sorts of probing and intimate questions. But I didn’t really know him. He hardly talked about himself. I’m not sure I asked.

———

SO: Was Fire Island the first sort of inkling that you had that Rev. Mullen might have been gay or bisexual, or when did that enter the equation for you? When did that thought enter your mind?

EM: It, it slowly dawned on me. But he seemed so not sexual. Now I think I, I think of him as kind of smarmy. He was this doughy Midwestern guy, very pale, and so not appealing. And he was old. So I didn’t think of him as a sexual being.

SO: You are literally describing me right now, Eric.

EM: I am not. Oh, my god.

SO: Doughy, Midwestern, and the exact same age that Rev. Mullen was. So I hope this isn’t too triggering for you. Um, tell me, what were your conversations, what were you getting out of these conversations that you weren’t from your friends or family?

EM: What’s so interesting about my conversations with Rev. Mullen is I remember almost nothing of the conversations. I do remember being in the car once—he was dropping me off, I don’t remember if we were coming back from Fire Island or from where… He asked me something about being bisexual and the hair on the back of my neck went up and I either ignored the question or said I didn’t know anything about that. I had not told anybody about what was going on in my head, and I wasn’t about to tell even Rev. Frank.

———

EM Narration: We’re back in Jamaica Estates, Queens. By now it’s 1976, and I’m 17 years old. Rev. Frank calls on a Saturday morning in early May. Can I come by to help him fix a leaky faucet in his en suite bathroom. A secret you might not know about me is that I’m actually pretty handy. I gather up my tools and head down the block. Rev. Frank greets me dressed in a crisp white shirt and pristine khaki pants. He is not dressed for plumbing work.

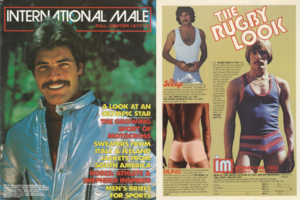

Frank leads me upstairs and into his bedroom. As we’re passing through, he picks up a magazine from his bed and asks if I’ve ever seen one of these before. I haven’t. It’s called International Male. If you can, look it up right now. There are a couple of mustachioed handsome men on the cover, dressed in what we’re gonna call “fashion-forward” clothes—super oversized bell bottoms, wild patterns, sexy leisurewear—and they’re showing a lot of skin. It’s sort of a cross between a physique magazine and a clothing catalog.

International Male means a lot to gay men of a certain generation. Seventeen-year-old me doesn’t know that, but it’s certainly making an impression. As I thumb through page after page of good-looking, muscular men in bathing suits, underwear, and kaftans, I’m trying really hard not to give anything away, because the clothes aren’t my style, but there’s a lot I see that I do like. If you know, you know, and if you just looked up International Male, now you know. Anyway, I get to the last page, hand the magazine back to Frank, and say, “Nope, never saw one before.” He tells me he has a stack of them if I’d like to see more. I say nothing and head for the bathroom for my date with the leaky faucet.

I know this sounds like a porn scene. Young guy, fixing a faucet, older man, offering magazines. But Rev. Mullen never laid a finger on me. I don’t know exactly what his deal was, but it for sure wasn’t that.

———

EM: Um, I led the way out of the bedroom, he was behind me, and passed an open door and heard a “Hello.” And, um, Rev. Frank rented a room or two to college students. We were around the corner from St. John’s University. Frank said, “Oh, come meet Bob.”

———

EM Narration: So I double back to the open door and the sight in front of me is like something out of a fantasy I didn’t know enough to have. Standing on a chair, in a pair of cutoff jean shorts and nothing else, is a beautiful young man, as sleek as a seal, on his tiptoes screwing in a light bulb. He says “Hi,” as the light bulb blinks to life with the final turn. He steps off the chair and reaches out to shake my hand, and introduces himself as Bob.

Bob wears aviator glasses, has an aspirational light brown mustache, fine light brown hair, and a body that is so breathtakingly beautiful to me that I can already hear my heartbeat pounding in my chest. Bob’s handshake is firm. His skin is warm, not sweaty, not dry. Perfect to the touch. We’re the same height, so when he looks at me, I can’t help but look straight back, for a few seconds too long, before getting nervous and turning away.

———

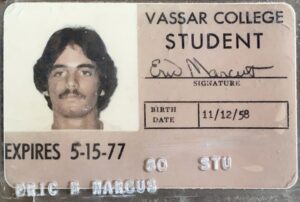

EM: Bob was a college student at St. John’s, I came to find out that he was 23. And Frank said, “Oh, Eric is going to Vassar in the fall, and Bob’s in college already. Why don’t you two chat?” So… I, I didn’t have to be persuaded to, to chat with Bob, and…

SO: A lightbulb moment in more than one sense.

EM: I was, um, smitten, and it was along the lines of, I want him. But it was also scary because I wanted him. I’m not sure I knew exactly what that meant or how I was gonna get there. Um, so Bob gets down off the chair. He’s finished putting in the light bulb. He flips the chair around so that the back of the chair is facing me, and he sits, straddles the chair and puts his arms over the, the back of the chair.

SO: Like Michelle Pfeiffer in the Dangerous Minds music video.

EM: Yes. And at some point in the conversation he says, “So when did you know you were gay?” I said to Bob, “Um, I never said I was gay.”

———

EM Narration: My actions in the weeks after meeting Bob spoke a lot louder than my words. I was totally besotted and worked hard at finding ways to see Bob that didn’t seem obvious, like watering the flower beds in the front yard at around the same time that I thought he’d be walking home from classes at St. John’s. It was hit or miss at first because it wasn’t the same time every day. But over a few weeks that spring, I figured out his schedule, and Bob would always stop to talk. On occasion he’d invite me over to help with chores or just visit over milk and cookies—always when Rev. Frank was out.

One afternoon when we were sitting across from each other at the kitchen table at Frank’s house, my leg accidentally brushed his leg, but he didn’t move. We were both wearing shorts. And I just let my leg rest on his. That’s when it happened again. That feeling of liquid bliss I remembered from the pool at the Caribe Hilton in Puerto Rico. Just like the last time. I didn’t know what to do about it. I had no experience with this sort of thing. I was 17 years old and I’d never even kissed another person. I’d read about heterosexual seduction in a couple of novels I’d found in the libraries of neighbors while babysitting. And there was a pickup scene between a teenaged boy and an older man in a book excerpt I’d read in Reader’s Digest. But I had no idea how I was going to get from that kitchen table to my bedroom or Bob’s. And I was scared. Scared because I didn’t know what to do and scared because of what it meant that I wanted to be with Bob so desperately.

———

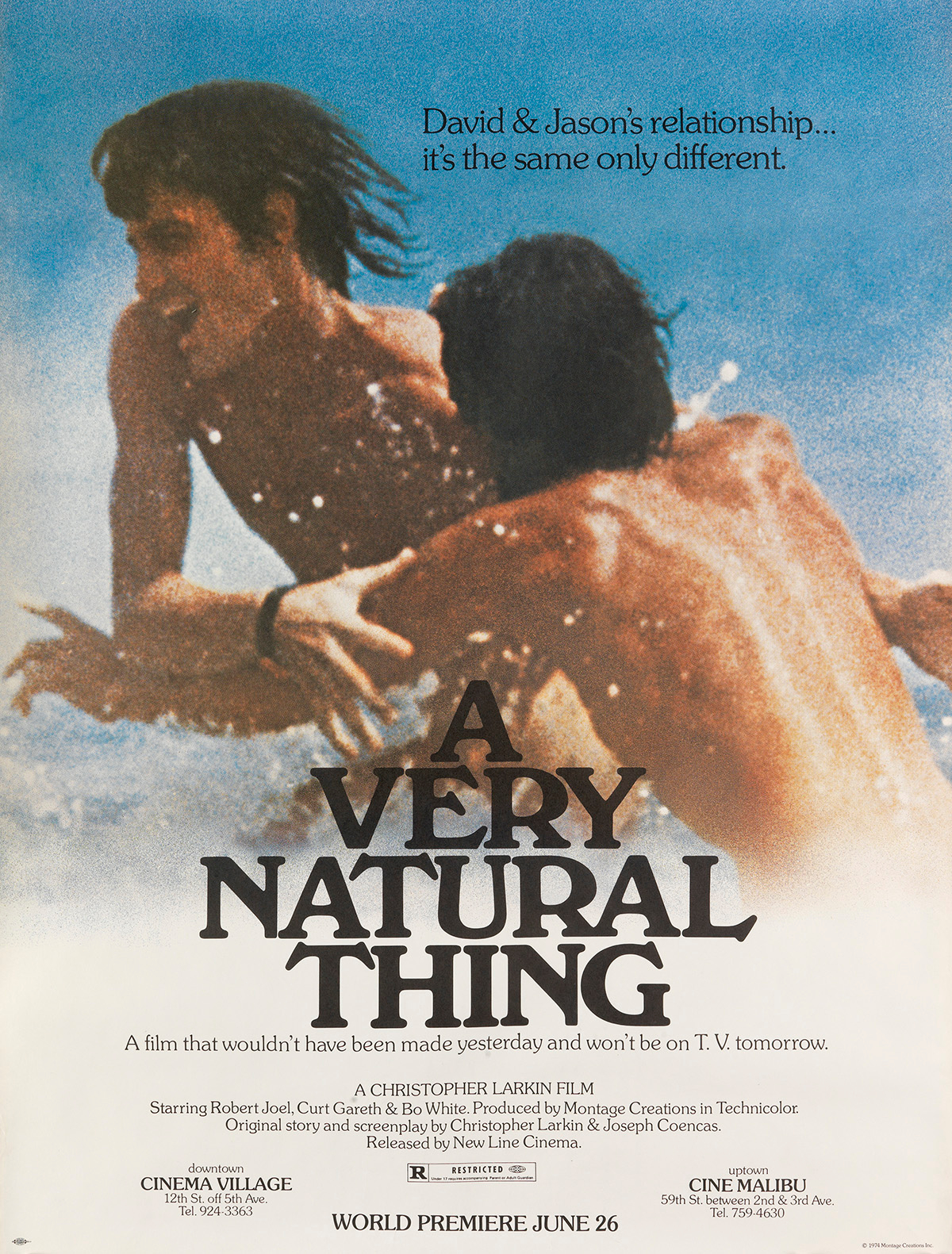

EM: At some point Bob invited me to go to a movie, um, in Manhattan. And I guess by that point I must have said something about being bisexual, I don’t know what. Uh, so we went to see a movie; it was called A Very Natural Thing.

SO: Indeed.

EM: And in the movie there’s, uh, actual footage of the 1973 march, uh, Gay Pride March.

SO: This, this was a movie explicitly about, about gay issues.

EM: Oh, it was a gay movie. No, it was about, it was about, it was a sort of a love story, kind of, sort of. I just remember the poster, which was two guys, um, frolicking in the waves at a beach.

SO: I’ve never heard of this movie. I’m kind of shocked.

EM: It’s, um, it’s, uh, it’s a long ago movie. Um, yeah, I think it’s A Very Natural Thing. I’m just gonna very quickly make sure that I’m talking about the right thing. Yes. There’s the—yes, there it is. There’s the, um… “A Very Natural Thing is a 1974 American film. The plot concerns a gay man named David, who”—what does he do?—uh, “leaves a monastery to become a public school teacher by day while looking for true love in a gay bar by night.”

SO: It’s like Taxi zum Klo but 30 years prior—20 years.

EM: Yeah, right. Um, “It was released to lukewarm reviews in 1973 and given an R rating.” So Bob and I went to see that. Um, and then, uh, he took me to my first gay bar. I was scared. Uh, it was Charlie’s East, which was very popular with people from Queens because it was just over the bridge or through the tunnel. Um, very smoky. It was incredibly smoky, and I felt safe with Bob, but it was scary. It was all older men. They were all over 20, probably some in their 30s.

And then we, um, headed home to Queens. Almost got beaten up on the subway by three kids who spotted us as gay, but we managed to escape them. And long story short, I dragged Bob home that night—and he had to be dragged because he was terrified. I was 17, I was underage. But at that moment I thought, if I don’t have him, I will die, in only the way a 17-year-old can act. And that night was the first time that I told anyone that I was gay. Um, because being wrapped up with him, in his arms, and having him in my arms, without our clothes on, was the first time in my life that I felt normal.

I had a great first experience with somebody who was very considerate of me and my age and where I was. And then we went to Jones Beach the next day with some of his friends and frolicked in the waves. That was magical.

———

EM Narration: One month later, my mother dropped me off in the parking lot of my dorm at Vassar college, turned around, and drove home. We were hardly speaking to each other by then, after a summer of increasingly tense conflicts over just about everything. She wasn’t going to stick around to help me settle in and I was happy for her to go.

I arrived at Vassar on that warm and sunny late August day intent on “fucking myself straight.” That was an actual expression people used back then. As transporting and blissful and revelatory as my experience with Bob had been, within about 24 hours of frolicking in the waves at Jones Beach, I felt crushed by the idea that I was a homosexual, and was determined not to be. From everything I knew about that life and the shame and secrecy and the guaranteed ruin that went along with it, I set out to find a girlfriend and leave men behind. I was so clueless that I thought such a thing was possible.

Within days, I found a girlfriend. I also attended the first meeting of the gay student organization—the Gay Alliance—under the pretense of caring about my gay friends. And I started secretly sleeping with an upperclassman who I met at the Gay Alliance.

I broke up with my girlfriend just before my 18th birthday in November, slept with various other guys, and, perhaps unsurprisingly, just about had a nervous breakdown. I spent the last week of the semester in the infirmary with a head-to-toe rash and a high fever. They sent a blood sample off to the major medical center in Albany, the state capital, but the various tests all came back negative. There was, of course, no blood test to diagnose a semi-closeted teenager who was deeply conflicted, emotionally exhausted, and very depressed. What I really needed was a therapist.

All during this time, there was one person I talked to routinely about what was going on: Rev. Frank. My long-distance phone bills were crazy. He was my emotional lifeline, asking me questions about what was going on, especially detailed questions about what I was doing with the men I was having sex with and how I experienced it. It didn’t occur to me until much later that there was a prurient aspect to what was going on and that he might have been getting off on my teenaged fumblings. Still, he was my lifeline.

When I think about Rev. Frank and my long-ago relationship with him, I find it easy to have compassion. He grew up in a very different world than I did and no doubt had to twist himself into a complex pretzel to navigate the world as a hidden gay or bisexual man. And however much he may have used me, he also introduced me to the life that I came to embrace. He also taught me, by example, how not to be a mentor to LGBTQ people, especially young gay men, a role that I deeply value.

By the time I started my sophomore year of college, I’d pulled away from Rev. Frank. I was mostly out of the closet at school, found friendship with a small group of classmates who I could talk to, and met a boyfriend my own age, whose parents embraced me and our relationship. I still struggled with coming to terms with my identity, but Rev. Frank was no longer my lifeline. I stopped calling and so did he.

Over the decades that followed, I thought of getting in touch with Rev. Frank to ask him about his recollection of those two tumultuous years. But I never did. And despite my increasingly high profile in the media because of my work as a journalist and author working in the gay space, he never contacted me. If I’m really honest about it, that still hurts. I’m embarrassed to admit it, but a part of me craved his approval.

In 2002 he moved back to the Midwest to be near his brother. He died at the age of 83 in 2014. Reading his obituary for the first time just the other day, it’s clear that he had a rich, productive, and varied life that I knew almost nothing about—and that there were aspects of his life that I did know about that it seems he kept secret from most people to the very end. May he rest in peace.

Next time on “Coming of Age During the 1970s,” “Family Ties,” the story of PFLAG.

———

This season of Making Gay History was produced and written by me, Eric Marcus, and Making Gay History’s founding editor, Sara Burningham, with archival research and production assistance from Brian Ferree. Special thanks to interviewer-slash-oral historian Shane O’Neill and a special thank-you, as well, to David Boyer for recording and producing his tour of the Fire Island Meat Rack. Our studio engineers for this episode were Katherine Cook and Michael Bognar. “Coming of Age During the 1970s” was mixed and sound designed by Anne Pope.

Many thanks to our hard-working crew at Making Gay History, including deputy director Inge De Taeye, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media producers, Cristiana Peña and Nick Porter.

This season was recorded at CDM Sound Studios. Our theme music and additional scoring were composed by Fritz Myers.

This season of the podcast was made possible by the generous support of the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, the Calamus Foundation, Andra and Irwin Press, Louis Bradbury, David Quirolo, Maria Lefkarites, and scores of other individual supporters. And big thanks to Patrick Hinds and Steve Tipton for their extremely generous support of Making Gay History’s mission to bring LGBTQ history to life through the voices of the people who lived it. Thank you, Patrick and Steve!

Please consider joining us on Making Gay History’s Patreon channel where you can support our work and at the same time gain access to exclusive interviews, behind-the-scenes conversations, and additional archival audio excerpts that we think you’ll enjoy hearing. Sign up for just $5 a month at patreon.com/makinggayhistory or just go to makinggayhistory.com and click on the Patreon button.

———

I’m coming back because it just occurred to me you might be wondering what happened to Bob. Mmm, Bob, okay.

———

EM: He holds a different place in my life than I hold in his life. So I was not so surprised that we fell out of touch, he was not interested in a younger person in that way. Um, although, you know, at 17, I thought, I’m going to marry this man, ’cause I was very much, I wanted to have, uh, a boyfriend. And despite everything that everyone was saying at that time, which was that gay men couldn’t possibly have long-term relationships, that’s what I was looking for. So I moved on when it was clear that he didn’t, he wasn’t interested.

Um, so I saw him again in 1988. The Male Couple’s Guide to Living Together had just been published and I was on a book tour. And I was in Philadelphia and he was living in that area then—he was a, a, a nurse. And he showed up at the book signing. And it was great to see him, and he gave me his number and said I should call. And I called, and I never heard from him again.

Uh, and then, 30 years ago, um, I was on a first date, when I was briefly single between my two long-term relationships, and I was walking in Battery Park City here in Manhattan with, with my date, first date. And I saw this young man with another, with a much younger man, uh, with his, a couple bicycles. They were standing, and, and, and the older of the two was taking his shirt off, which obscured his face, but I thought, I know that body. I know that body.

SO: So can you recognize people by their abs just in general? Like, is that a skill you have?

EM: At 17 I was so deeply imprinted with this, this one young man. Um, no, no, that’s, no, I can’t. But I did recognize Bob right away, and he was as beautiful as I remembered him. And we chatted and, um, he, he gave me his number again and said, “Call me. I’d love to get together.”

SO: Wow.

EM: It’s more than 30 years. I left a message. I’ve never heard from him again. But I did write about him in Newsweek, and he had said to me when I ran into him—it was probably about 1992 or 19…, it was ’92—he said, “I read that piece in Newsweek. I wondered if that was the Bob you were referring to.” It’s like, “Bob, like, of course it was you.” Um…

SO: Have you Googled him?

EM: Of course.

SO: That was, that was sort of the litmus test to make sure we’re having an honest interview here.

EM: Of course. And, and I thought, should I go back and interview him to ask him what his experience was of that, and what it’s been like through his life to know that he turns up every now and then in my work? Because he’s not a public person.

Um, but, you know, he gave me a book called Men and Masculinity, which, uh, was an exploration of, of what it meant to be a man. It was a very meaningful book to me, and also helped me understand what it meant to be a gay man, and a responsible gay man.

So in that regard, I’m very, I was very fortunate that he was such a good person, as opposed to people who were not looking out for my best interests.

———

EM Narration: “Coming of Age During the 1970s” is a production of Making Gay History. I’m Eric Marcus. So long, until next time.

###