Bonus Episode — From the Vault: Sylvia Rivera & Marsha P. Johnson, 1970

Brian Ferree finds the 1970 “Interview with Members of S.T.A.R.” in the basement of the Lesbian Herstory Archives. Credit: Photo courtesy of Brian Ferree.

Brian Ferree finds the 1970 “Interview with Members of S.T.A.R.” in the basement of the Lesbian Herstory Archives. Credit: Photo courtesy of Brian Ferree.Episode Notes

In 1970, a young radio reporter recorded an interview with Sylvia Rivera, Marsha P. Johnson, and other members of the newly formed Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries—STAR. Nearly 50 years later, MGH unearthed their remarkable conversation in a basement archive.

Episode first published December 27, 2019.

———

From Eric Marcus: In the spring of 2019, as we were working on our Stonewall 50 season, Sara Burningham, Making Gay History’s founding editor and producer, asked our researcher and self-described archive rat Brian Ferree to hunt down whatever audio he could find related to the Stonewall uprising—the lead-up to the uprising, the uprising itself, and the year following.

Brian’s hunt led him down into the basement of the Lesbian Herstory Archives in Brooklyn, New York. Though his search there turned up nothing that he was looking for, he stumbled on a box containing a long-lost recording from 1970—an interview with members of the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR)—which we’re featuring in this episode, along with my interview with Brian about his discovery.

I’ll let Liza Cowan, who recorded the 1970 interview, pick up the story from here.

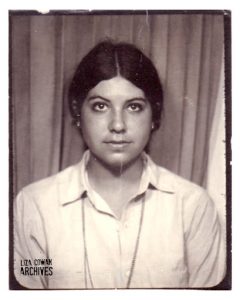

From Liza Cowan: In December of 1970, I was 20 years old, and working as a staff producer and reporter at WBAI-FM, listener-supported radio in New York City. It was a year before I came out as a lesbian. I was new to feminism, and I’d had no previous experience with people who at the time were referred to—and referred to themselves—as “transvestites” or “cross-dressers.” But I’d always been interested in clothing. And I was curious. I decided to interview some transvestites about clothing and sex role stereotypes.

This was two years before I began to write my series “What the Well Dressed Dyke Will Wear” for Cowrie Magazine and then for DYKE, A Quarterly. My 1970 interview with STAR would have been a precursor to that series had it gone the way I’d imagined it would. It didn’t.

My initial interest was in how humans are affected by the clothing we wear. Do we change our mannerisms when we change our clothing? If so, which comes first: intention or clothing? Are men more “manly” when they wear suits and ties? Are women more “womanly” when they wear dresses and high heels? And, if so, what happens when we swap the clothes we are supposed to be wearing for clothing made for the opposite sex? That was the question I hoped to explore in my WBAI piece.

Because I didn’t know anyone who would suit my needs for the interview, I asked my WBAI colleague Charles Pitts for some leads. Charles was the first out gay man I had made friends with, and pretty much everything I knew about being gay I’d learned from him. Charles directed me to Craig Rodwell, who had opened his Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop just a few years earlier.

I went over to Mercer Street to ask Craig for suggestions and he put me in touch with some people he thought would be willing to talk. I contacted them and they agreed to meet for an interview. I took a taxi down to a tenement building on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, walked up several flights of stairs, and entered into a small apartment.

I don’t know whose apartment it was. Possibly it was STAR House on East 2nd Street where Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, just recently formed, was headquartered. Possibly not. This rundown neighborhood, historically the home of immigrants, was now also attracting artists, beatniks, and hippies who could afford the cheap rents or even find places to squat rent-free. A few blocks away, the 5th Street Women’s Building Takeover, a feminist offshoot of the community movement in opposition to the Model Cities urban renewal program, was being planned for the following month.

In the apartment, I met Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, someone named Victor, and Mark Giles. Mark [not heard in the episode] was not trans. She was a butch lesbian, unique in being herself, but not so different from the many lesbians of that era whose look consisted mainly of jeans, button-down shirts or T-shirts, comfortable shoes, and short hair. She worked as a bartender at Gianni’s, a lesbian bar in Manhattan, and had recently been involved in the creation of the periodical Come Out! along with Roz Bramms, Martha Shelley, Suzanne Bevier, Kay Tobin, Lois Hart, Marty Robinson, Jim Owles, and a host of others. I think her profession was typesetting. She told me that she had worked at TV Guide in Los Angeles, which I thought was mighty impressive.

The apartment was dark and chilly on this cold winter night. What heat there was came from the steam pipes, which were banging and hissing so hard I was afraid that my sound recording would be spoiled. We drank tea and began to talk.

The stories I heard were all news to me. I’d been living in Italy during Stonewall, and hadn’t paid much attention to what was happening in gay New York. I wanted to talk about clothing. Marsha and Sylvia wanted to talk about the political actions they were involved in. I sensed that their stories were going to be more interesting, mostly because it was what they were passionate about. So that’s mostly what we discussed.

Now, almost 50 years later, the interview has been retrieved from the depths of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, where it ended up in the wrong box after I donated it decades ago. I thought it was lost forever. And since it turns out to be the first known recording of Marsha and Sylvia, I’m glad we talked politics.

———

To learn more about Liza Cowan’s interview and details about the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries and STAR House, read this article from Women at the Center at the New-York Historical Society.

Find out more about Sylvia Rivera in our two-part 1989 interview with her here and here.

For more Marsha P. Johnson, listen to this MGH episode, which features a 1989 interview with her and her then-roommate, fellow activist Randy Wicker.

Marsha and Sylvia were also featured in the second and third episodes of our Stonewall 50 season.

For a deeper dive into the lives and activism of Sylvia and Marsha, check out the resources listed on the webpages of each of the episodes linked above.

A note from Liza Cowan about how old audiotape was edited: “The tapes were edited using Scotch tape, not glue. Literally Scotch tape, but not the kind you use to wrap gifts. It was a special size tape and adhesive, made by 3M, or Scotch, to use with the magnetic recording tapes that they also manufactured. The entire editing process was done by hand, using special reel-to-reel players [see photo in transcript below] with a special little channel where the tape would go to be carefully sliced with a razor blade and then stuck together in the right place with tape. It was difficult, time consuming, and most definitely a learned skill.”

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus—and this is a special bonus episode of Making Gay History!

The sixth season of our podcast has focused on LGBTQ activism in the post-Stonewall ’70s. Two of the most prominent trans activists to emerge out of that period were Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson. In 1970, the year after the Stonewall uprising in New York City’s Greenwich Village, the two friends founded Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries—or STAR—and set up a bare-bones refuge in a rundown apartment building on the Lower East Side of Manhattan for street kids much like themselves. They called it STAR House.

In December 1970, Liza Cowan, a 20-year-old reporter for WBAI radio, conducted what we believe is the oldest recorded interview with Sylvia, Marsha, and other members of STAR. She used a reel-to-reel tape recorder and set out to do a story on what was then known as “cross-dressing.” Eventually, a single reel containing an edited version of the interview found its way into the basement of the Lesbian Herstory Archives in Brooklyn, New York. And that’s where Making Gay History’s self-described archive rat, Brian Ferree, found it in the spring of 2019.

Before we share some of that incredibly rare tape with you, I thought I’d ask Brian about his experience of discovering this long-lost interview.

———

Eric Marcus: How did you find this tape? Where were you and what were you doing?

Brian Ferree: So I was looking for audio for the fifth season of Making Gay History, for our Stonewall season. And my mission was to find archival audio tapes that were made around 1968 to 1971. So I went to the LGBT Center Archives, I went to the New York Public Library, and I went to the Lesbian Herstory Archives. In the basement of the Lesbian Herstory Archives I was going through all of their cassettes for WBAI shows. I didn’t find anything that reached back that was applicable to what we were looking for, but out of the corner of my eye in the basement, I saw a box of open-reel, open-reel audio, which is an older style of audio recording than cassettes would be.

EM: So what is…? Can you describe what open-reel, uh, recording is? Is it like, is it—you see in the movies or in photographs—an actual reel of tape?

BF: Yes. These are the big reels. These are like, well, three inch, five inch, seven inch, 10 inch… And I didn’t know what was in this box when I saw it, but I went upstairs to the volunteer archivist, Rachel Corbman, and I asked her if I could go through it.

And right there in the middle of the box, I pulled out this recording that was labeled “STAR.” I was afraid to open it because some of these tapes, they’re so fragile when they’re 50, 60, 70 years old, they are so fragile that you can destroy them, and I know how difficult it is to get archival material surrounding STAR.

EM: Yeah. So what did you, when you saw this, besides being afraid that you would, you could possibly damage the tape, um… I mean, it’s almost like finding the Holy Grail.

BF: You know, you want to listen to it immediately when you find a tape like that and you can’t.

EM: Why couldn’t you just play it?

BF: Well, for one, there are some tapes that, as you play it, they will erase when they’re 50 years old. So you will listen to it, but nobody else will.

EM: So if you want to have a tape digitized like that, what do you do?

BF: We took the tape to a studio in Harlem called Swan studios that specializes in this type of digitization. I took so much care when I took it out of that building. I was so afraid of damaging it. It was like I had $10,000 in my backpack and couldn’t let anyone near it.

So I arrived at Swan studios in Harlem and Robert, the sound engineer, started rewinding the tape, and when he did, every single manual edit snapped.

EM: Oh my. So this is an edited… This was an interview that was done that was then edited. And, and, and how did they edit tape?

BF: Well, they had to take it physically and slice it, and then with adhesive, glue it back together. So each and every time it hit one of these physical edits, it would snap, which for me was terrifying, but for him was just run of the mill. He would just take the two ends, reapply adhesive, and keep rewinding it.

EM: Once he rewound it, what did he do next?

BF: Well, he was kind enough to let me sit in the studio and listen to it as he played it for the first time, and I knew I was listening to something very special.

EM: What made it special?

BF: It was special for me because they’re not just talking about the organization that they created. They’re also talking about their lives, and they’re talking about how they see the world around them and how they see gender. It’s all very personal. They’re not all toeing the same line.

EM: What did you take away from hearing that recording?

BF: I think it reminded me of how young everyone was then. I think the Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera that I’ve grown accustomed to, they were older by the time, um… The film that I’ve seen of them, the video that I’ve seen of them, the recordings that I’ve listened to from them, they had more time under their belt, and this, it was, it was like they were freshly arrived in New York and just letting it all out.

———

EM Narration: The quality of the tape you’re about to hear in this remarkable and far-ranging conversation is a bit uneven. In addition to a snippet of Jefferson Airplane, you’ll also notice hissing in the background during part of the discussion. Anyone who has ever lived in an old New York City apartment will recognize that sound. It’s coming from the faulty valve of a steam heat radiator.

The first person to speak is 19-year-old Sylvia Rivera. The second is someone named Victor, and the third is Marsha P. Johnson, who was 25 at the time.

———

Sylvia Rivera: Before my mother passed away, my, my first three years, my mother used to dress me in girls’ clothes and my mother… My grandmother kept on buying, like, little blouses and girls’ slacks until about I was six or seven years old, before I went into school. Then she started dressing me in boys’ clothes. During that period, that’s when I discovered my homosexuality with, like, you know, watching television and placing myself in the role of the female or just placing myself as another, as another boy, and the males, um, and the, and the man that was playing such a fantastic love role on the television.

And, um, I found when I left home at 11 was really when I went into transvestism and makeup. Um, hustling in the streets and the games, I guess, whatever you want to call them.

Victor: My, uh, experience is different from Sylvia’s. I, I did it all secretly because, uh, if my mother would catch me, she would forbid it. And, um, by the time I was five years old, I knew enough that, uh, uh… to do these things secretly. Uh, so I used to, when no one was around, put on makeup and, uh, wear, um, women’s clothes I could get my hands on. But otherwise I grew up quite masculine. I went to school, I played baseball, I went to college, so… And, um, I even grew a beard and was a revolutionary. I did time in jail for, uh, pacifist demonstrations.

And, um, just recently, um, I decided what’s, um, you know, why not wear the clothes I prefer to wear? And I was, I was, um… All this time I was living a masculine role that, uh, I didn’t really prefer. At least I didn’t prefer to do it permanently. I preferred at times to be feminine.

Women’s lib people, um, feel that, um, women are forced to take certain roles which are unacceptable to them. And, uh, they want to break out. Now, I’ve often, uh, felt the same way about being a man, that I’ve been forced to take certain roles. Uh, number one, something as unimportant as the clothes, uh… I have to wear men’s… The restrictions on men’s dress are much more severe than the restrictions on women’s dress, so men are forced to look a certain way and I didn’t want to look that way. And, of course, there’s the… A man has to, uh, be tough. He has to have responsibility. He has to take care of people. You know, suppose I wanted to be, uh, petted or I wanted to be taken care of?

Marsha P. Johnson: As I was growing up, I met a lot of men. They never appealed to me, you know, too much sexually. I used to try and keep away from them because in my hometown, you were homosexual, you were out of it. And they would call you all kinds of names. Um… And then when I first came to New York, I was 17 years old. That’s when I started getting kind of transvest—more like a transvestite.

I started out with makeup in 1963, 1964. And in 1965 I was coming out more and I was still wearing makeup, but I was still going to jail, just for wearing makeup. In 1969, I started wearing female attire full-time.

Usually I wear a short dress every day of the week. I just don’t put on much makeup anything until after dark because it draws too much attention. If I were to wear a lot of makeup in the daytime, they might think that I was a male. But if I wear a little makeup, they think I’m a female and they just let me ride on by. And if I wear a lot of makeup at night, they automatically know I’m female. They really can’t tell the difference about me because I’m on my way to be a sex change.

I have hormone treatments, and my bust is, uh, about a, a small… It’s a small bust, but it’s a nice handful and they feel that nice handful and they automatically go into the illusion that I might be real. From going into hormones, I’ve gotten so that I, I kind of, kind of just like heterosexual men. And if I was to marry a male, it would strictly be a gay male because I don’t care for heterosexual men as a husband. They’re too, they’re too, uh… I can’t think of the word, but it’s too masculine for me.

SR: Too oppressive. Be more realistic about it.

MJ: I could always talk like a woman. I could always act like a woman. I could always do things that women would do because I was raised by my mother. Like, I could wash, I could iron, I could cook, I could sew. I can, um…

Unidentified Speaker: That’s very oppressive…

MJ: Well, that’s what they’re good for doing.

Unidentified Speaker: Oooh! Stop!

MJ: That’s what women do. That’s what my mother always did. Well, some women don’t do that, but my mother was poor. She had to do it all herself.

SR: I, as a person, don’t believe that a transvestite or a woman should do all the wash and do all the cooking and do everything that was forced on by the bourgeois society and the establishment that women have to do this. I don’t believe in that. That’s a whole lot of baloney. If you have a lover or you have a friend that you really care for, you split everything down 50/50. If you don’t feel like doing it, you just don’t do it. Let him do it. Because this is what we’re all trying to get across. Men are oppressive. They just oppress you in all different ways.

V: All transvestites have a, a very feminine image. Some of it is, um, a Marilyn Monroe type of sexpot. Some of it is a motherly figure. Mine was a fashion model.

Girls have always told me that, uh, they have trouble at night. Men bother them.

MJ: We do, too.

V: Uh, well, I, I never believed them until I went out in the street in drag for the first time. And the first time I decided it would be best at night. People couldn’t see me very clearly. I went out and, um, men start following me and they make lewd remarks to me in my ear. I got so scared.

MJ: They’re trying to pick you up.

SR: I’ve met many a man through my hustling experiences that were transvestites but were married. They were supposed to be heterosexual males. At this time, like, I would be dressed in unisex clothes and flamboyant hairstyles and makeup and the whole bit, you know. And they would come up and proposition me. And I was, you know… They would like to wear my female clothing, uh, or either go with me to a store and help them shop so they can come to my house and I showed them how to dress and put on the makeup and whatnot. They would just get their kicks, the, the sexual satisfaction by being in female clothing. Like, I never knocked them. I just, I just don’t understand it.

I knew a person that was a female impersonator on stage—transvestite. And she was forced into coming out to the public and say, “Look, I’m a heterosexual male, not a homosexual.” I think what… I think if these men would get their heads together and start facing this and… It’s really beautiful because it’s like the same thing a homosexual transvestite has to go through with telling their family.

Like, my grandmother completely freaked out for a number of years until she just recently has to be satisfied that I’m, that I’m going to be my way. And now she calls me Sylvia. I’m her dear granddaughter. I’m all this, you know.

Society keeps on saying, “You can’t do this because this isn’t your role.” Who is to tell who what role we’re supposed to take?

I was at a demonstration, um, when the gay people, um, charged, um, the United States with genocide. And this person wrote a paragraph or more, you know, a short thing on when we, the street people and transvestites, appeared on the scene. So right away he throws everything on me. And he starts off, “Mr. Ray Rivera… Mr. Rivera likes to be called by his transvestite friends as Sylvia.” This is very oppressive. I… Everyone calls me Sylvia. My name is… I’ve had this name for nine years, straight or gay. Even on my job, the girls that I used to—the women that I used to work with called me Sylvia. And, like, it’s not just transvestites that call me Sylvia or consider me or treat me as she. They, this is what… People respect you. This is respect.

Like, um, Marsha was written up in the same article. “A Black male transvestite.” Why does he have to say what you are? Just say “transvestite.” Do not… Not “he.” But if he doesn’t want to put down “she”… Because I think whatchamacallit, if he’s gonna write, he shouldn’t classify people. Just say “transvestite” or, um, um, “The transvestite brigade showed up,” or whatever.

But he did very wrong, like, to say, to classify people like me as “Mr. Ray Rivera” because, like, um, he knows me from Gay Activists Alliance when I first joined there, like, um… I was there when GAA first started, four months, when it was four months old. And, like, um, I was… I made a phone call from Jersey and said, “Do you accept transvestites?” At that time, I was still using the word “drag queen.” I said, “Do you accept drag queens?” “Sure, come on down.”

So my friends and I tipped down there to the meeting from Jersey, and we walk in, we took a peek, and it was nothing but butch male homosexuals that always oppressed transvestites. And we were very flamboyant with the makeup and everything, you know, tipping in, you know, really looking… beautiful. So, like, we walked away. We walked up the block and we came back and we peeked in some more. I said, “No, let’s go home.” We walked about five blocks. I said, “No. Let’s go in and freak them out for the hell of it.”

So we walked in, and like, um, … “What’s your name?” At the table, you had to write your name. I said, “My name is Sylvia.” He says, “What is your name?” I said, “I’m Sylvia!” He says, “Well, we can’t accept that name.” So I wrote down “Sylvia Lee Rivera,” but in parentheses I have the habit of putting “Ray Rivera,” my real name. Even butch-identified, even men, you know, homosexual males that are dealing with their sexism are always discriminating against transvestites because they just can’t… We’re threatening their masculinity. That’s the way they feel.

I would never go, I would never… I’ve never been to bed with a woman. I’ve never… I would never marry one. I would never consider even the sport. But I as a person could never see myself going to bed with a woman.

V: Oh, stop.

SR: Women terrify me as far as that goes. I’m sorry. I’m being realistic. I’m actually… Like, I, I love to be around women. I can’t stand to be in a room full of males because they get me uptight. I get very uptight. Like, you know, they look at me and, like, you know, I get very uptight. I like, um… With women, I’m more free. You know, like, they understand. A woman seems to understand because you’re gay and you’re a transvestite. They understand you more than a male does and they won’t ridicule you that much.

I’m dealing with my own, my own problems. Like, self-discipline is like, um, trying to deal away with using the term “Miss Thing” or “drag queen.” Like, before when he called me “Miss Thing,” I had to hit him because I don’t like it. “Mary.” We got to get rid of that.

Unidentified Speaker: It’s very oppressive.

Liza Cowan: Do you ever go to, um, drag balls?

SR: I’ve been to two. I don’t like drag balls. I don’t believe that… Like, I don’t believe in competition. And, like, everything there’s competing against each other and it’s like, if you feel you should’ve won the first prize, the first trophy, grand prize, these break into fights. All this violence. I believe in fighting violence. For god’s sake, go out and beat up a pig or something, but don’t beat up your sisters for, for the reason because you thought you made a better gown than she did and you should have this trophy.

———

EM Narration: Both Sylvia and Marsha remained very visible participants in the battle for equal rights in New York City. They’re remembered today as iconic and pioneering trans activists.

Marsha P. Johnson died in 1992. She was 46. Sylvia Rivera died ten years later at the age of 50. To learn more about their lives and STAR House, have a listen to Making Gay History’s three episodes featuring my 1989 interviews with Sylvia and Marsha.

———

Many thanks to everyone who makes Making Gay History possible: senior producer Nahanni Rous, producers Josh Gwynn and Andre Bellido, deputy director Inge De Taeye, audio engineer Jeff Towne, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media team, Cristiana Peña, Nick Porter, Denio Lourenco, and Will Coley. Special thanks to Jenna Weiss-Berman and our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

A big thank-you to our researcher Brian Ferree, for unearthing the STAR interview you just heard, and to Liza Cowan, who recorded it back in 1970. After her stint at WBAI, Liza went on to write for Cowrie magazine and later became editor and publisher of DYKE, a Quarterly. Today, she’s an artist and graphic designer; you can find her work at smallequals.com.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Studios, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

This podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, the Calamus Foundation, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, the Small Change Foundation, Irwin and Andra Press, and our listeners, including Rob Darrow. Thanks, Rob!

Stay in touch with Making Gay History by signing up for our newsletter at makinggayhistory.com. Our website is also where you’ll find previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature.

So long! Until next time!

###