Barbara Smith

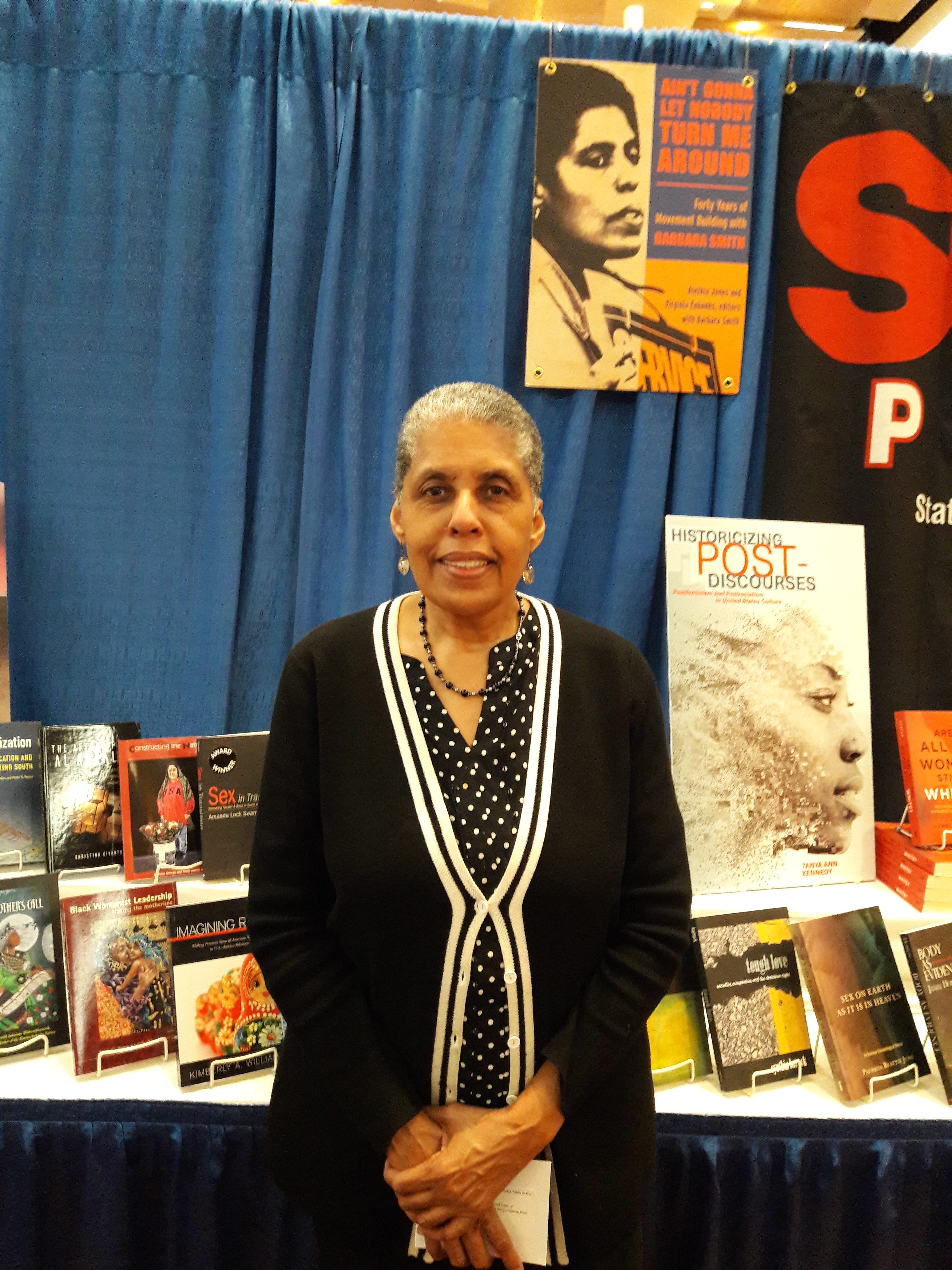

Barbara Smith, Albany, New York, August 1987. Credit: Photo by Robert Giard © Jonathan Silin courtesy of the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library.

Barbara Smith, Albany, New York, August 1987. Credit: Photo by Robert Giard © Jonathan Silin courtesy of the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library.Episode Notes

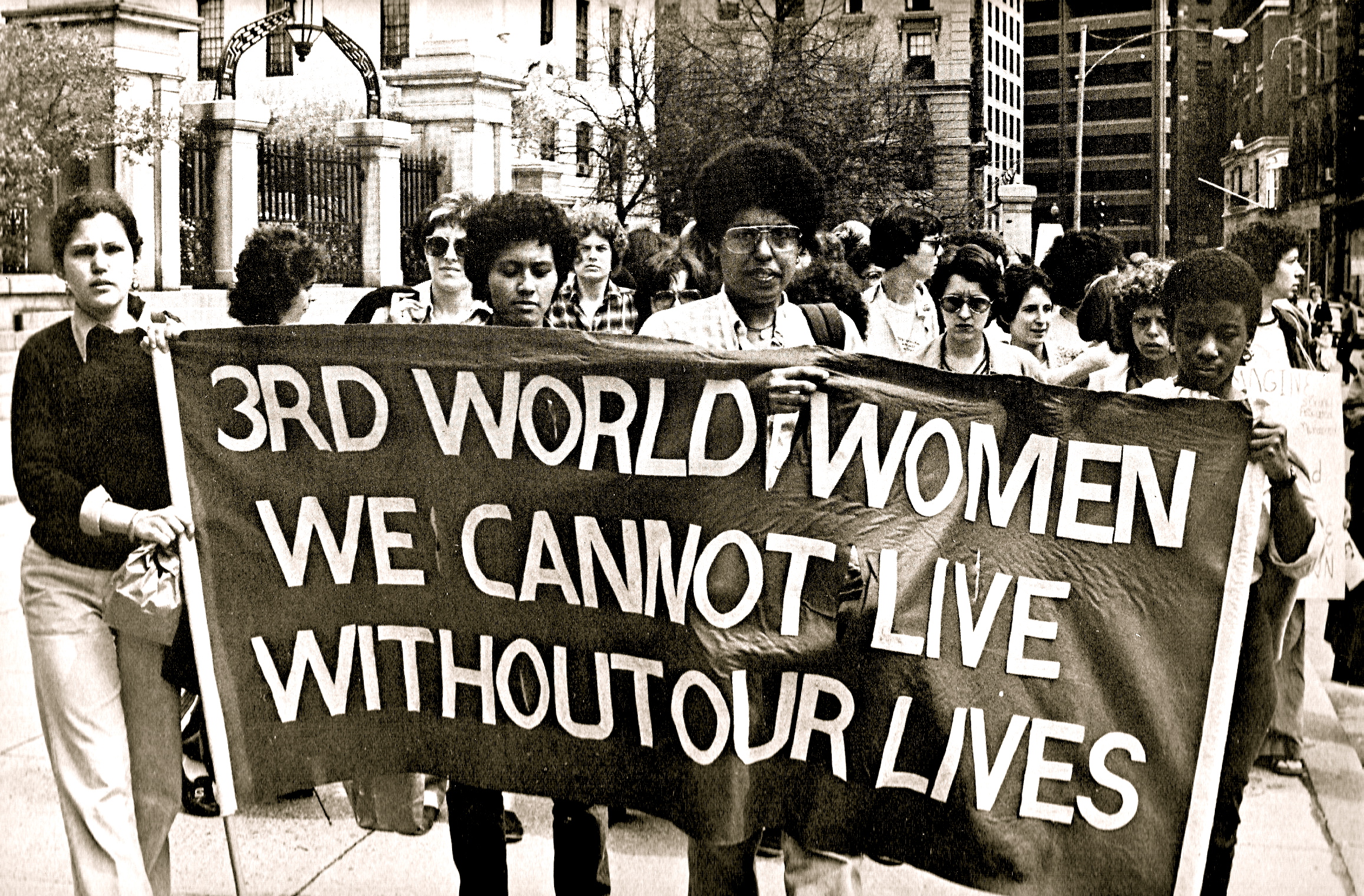

For nearly half a century, Barbara Smith has been speaking truth to power—as a woman against misogyny, as an African American against racism, as a lesbian against homophobia, and as a Black lesbian against those in the gay rights movement who sideline the concerns of LGBTQ people of color.

Episode first published November 21, 2019.

———

From Eric Marcus: Barbara Smith inspires me to sit up straight, pay attention, and strive to do better. That’s the power of her unapologetic truth-telling, passion, and open-hearted joy for life. We first met in my living room in upstate New York nearly two decades ago for one of a dozen new interviews that I conducted for the second edition of Making Gay History. (The other interviewees included Al Gore and Ellen DeGeneres, among others.)

It was Barbara’s founding of Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press and her involvement in the 1979 National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights that caught my interest, but those topics were only the jumping-off point. We had a memorably far-ranging conversation about her lifetime of activism and scholarship—all accompanied by plenty of laughter, although some of the laughter you’ll hear is my incredulous response to the shocking things Barbara shared with me. Have a listen.

———

Get better acquainted with Barbara Smith by watching this short video. For an in-depth look at her life and work, read Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around: Forty Years of Movement Building with Barbara Smith, edited by Alethia Jones and Virginia Eubanks. Listen to Barbara talk about coming out here, and check out her oral history, which is kept at Smith College.

For more on Barbara’s broad and intersectional social justice agenda, read this Autostraddle interview and watch this lecture. Read about her frustrations with the mainstream LGBTQ civil rights movement in the Nation and the New York Times. Watch Barbara in conversation with young Black feminist leaders here. For a list of books she’s written and edited, go here.

In 1974, Barbara co-founded the Combahee River Collective. She was one of the primary authors of its statement, a powerful articulation of lesbian-inclusive Black feminist politics.

In 1977, Barbara published “Toward a Black Feminist Criticism,” the groundbreaking essay that prompted her invitation to speak at Howard University the following year. Learn more about Frances Cress Welsing, the psychiatrist who responded to Barbara’s speech by declaring homosexuality “the death of the race,” here.

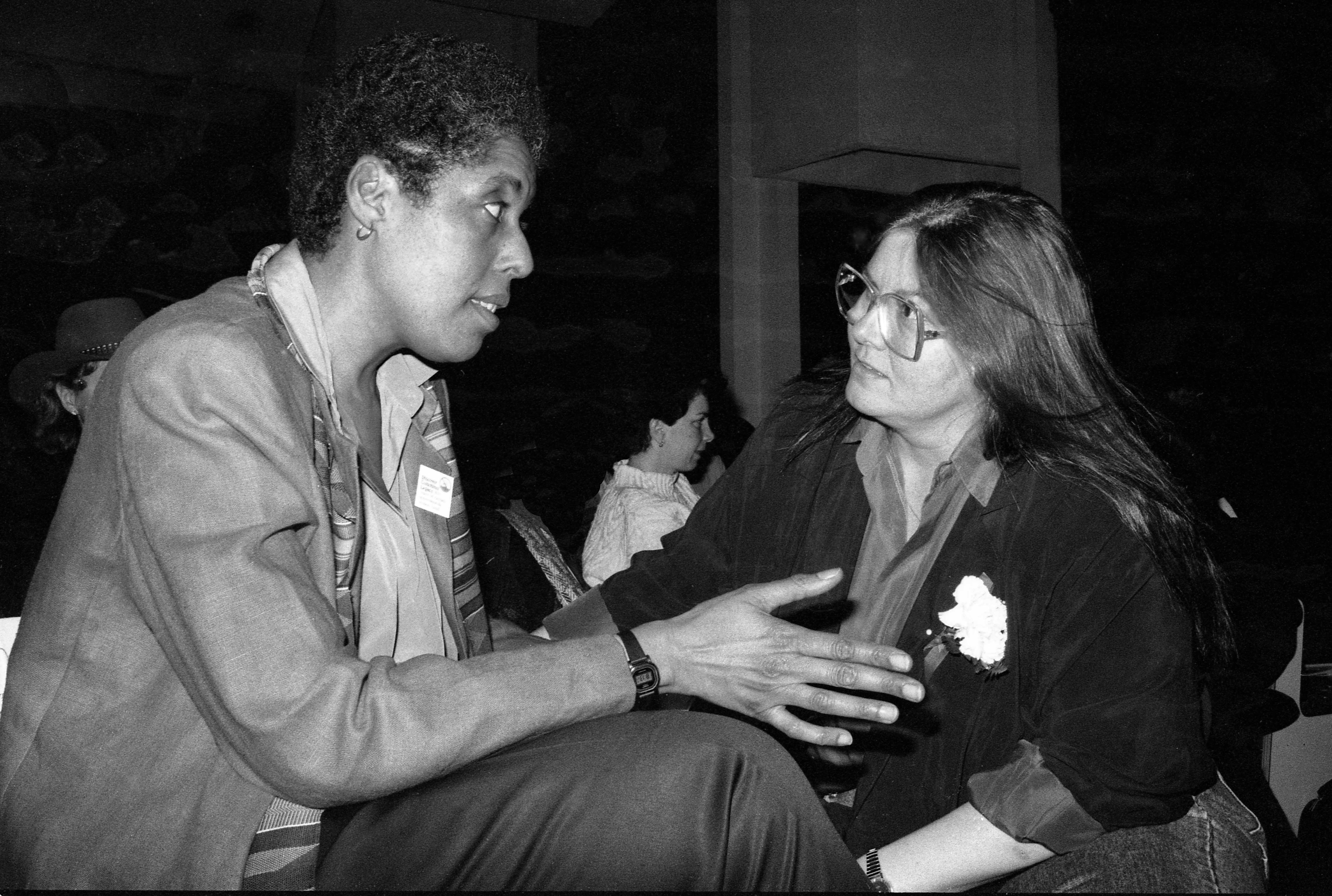

In 1980, Barbara and her friend Audre Lorde co-founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, the first national publishing company run by and for women of color; Barbara describes the founding of the press in this essay. Kitchen Table published dozens of works, including Barbara’s own Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology. You can read it here and hear Barbara talk about it here.

To learn more about Audre Lorde, watch this short video, listen to this interview about her experiences as a young Black lesbian in 1950s New York City, or read her poetry. For more audio recordings of Audre, visit the Lesbian Herstory Archives website.

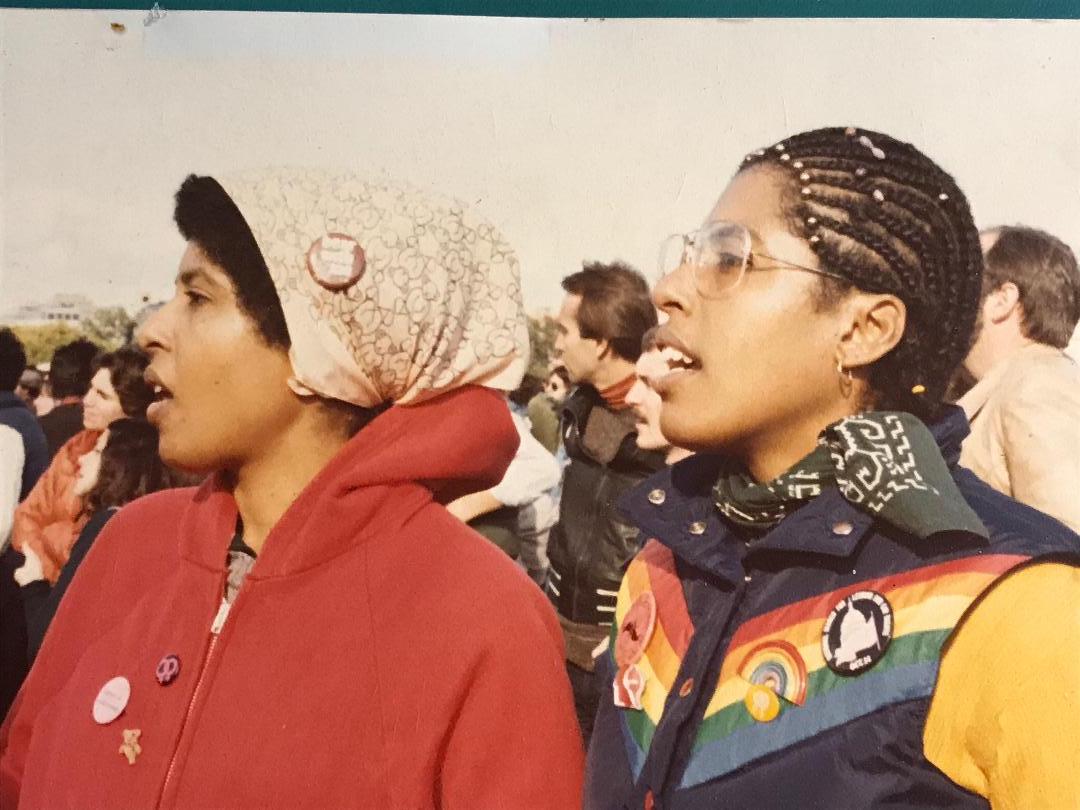

At the top of Barbara’s Making Gay History episode, she describes a photo of her and her sister at the 1979 National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights (you can see it below). Read more about the march here and listen to the speech Audre Lorde gave to the many thousands who assembled for the march’s rally. Hear more audio from the march here and here, and read the program of events.

———

Episode Transcript

Eric Marcus Narration: I’m Eric Marcus, and this is Making Gay History!

Barbara Smith has never been a single-issue activist. Her entire life she’s demanded justice and dignity for those whose voices aren’t heard. That’s just how she was raised.

Barbara and her twin sister Beverly were born in 1946 in Cleveland, Ohio. That’s where the family had settled after leaving small-town Georgia in the Jim Crow south. Their mother, Hilda, the first person in the family to earn a college degree, died when they were nine. The sisters were then raised by their extended family, in a household of women who put great stock in education.

In the mid-1960s, Barbara attended Mount Holyoke, an all-women’s college where she later recalled she was surrounded by “lesbian undercurrents that were not spoken.” At the time, Barbara wasn’t aware of any gay rights efforts, and while her feelings for women were nothing new, she didn’t come out until the mid-1970s.

In 1974, Barbara co-founded the Combahee River Collective, a Black feminist organizing group dedicated to the struggle against “racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression.” In 1980, Barbara and Audre Lorde—the self-described Black lesbian feminist mother poet warrior—co-founded the Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press. It was run by and for women of color whose writings got short shrift by the mainstream publishing industry.

By the time I interviewed Barbara, she’d been speaking truth to power for decades—as a woman against misogyny, as an African American against racism, as a lesbian against homophobia, and as a Black lesbian against those in the gay rights movement who sidelined the concerns of LGBTQ people of color.

So here’s the scene. It’s January 29, 2001, and Barbara has driven from her home in Albany, New York, to my weekend place a half hour south. We’re seated on an overstuffed sofa looking at photographs that Barbara brought with her. She shows me a photo of herself and her twin sister at the 1979 National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights.

———

Barbara Smith: This is my sister and me at the march in ’79.

Eric Marcus: Oh my!

BS: And I’m the one on the right, with my hair braided. And I was thinking about that as I pulled that picture out. I mean it took hours to get my hair braided. I only did it, like, a couple of times. Because I am so not into the muss and fuss of it all. I was thinking, like, just seeing the fact that I had my hair braided shows how special I thought this march was.

EM: Do you recall anything in particular about the march? People who spoke or other impressions?

BS: I just remember the feeling of incredible joy. And being there. And excitement. There is such a kick in being visible and out, you know. And doing that in a mass way. I think that if one is, like, manifesting or if one is visible, and by yourself, that’s really kind of scary. That scares me. To this day. But the thing is to have the support of numbers.

Everything, like this is a general statement about the ’70s. Or the second half of the ’70s, which was the period when I was first out. There was a feeling that we could do anything. I had the feeling that we could do anything. That everything was possible. Um, because we were toppling such mammoth taboos and such mammoth notions.

EM: Such as…

BS: That women were supposed to, you know, be passive. And stay at home and have babies. And in a Black nationalist context, stay home and have babies for the Nation. There’s an extreme amount, it seems to me, of male chauvinism in a certain Black context, which is a direct result of racism and the deficit of never being able to lead and have freedom in a racist country. So to make up for white supremacy, in certain Black political contexts, the Black men are even more chauvinistic. Because they’re really going to show, you know, who’s boss. Because they are so rightfully angry about not being recognized as capable and full human beings in a context where white men get to call the shots.

Being a lesbian feminist as I was in that period was about just sticking holes, you know, in every cherished value and belief.

EM: When you say you were doing feminist lesbian work, what do you mean by that?

BS: There was a actual lesbian feminist movement which was very vital and had great positive impact on the way that issues in a variety of movements were shaped and were defined during that period. And we worked with gay men. Like, you know, we were able to work with gay men, you know, who were ready to deal with us as non-second-class citizens. So the thing is that the line between, you know, lesbian feminism and feminism and the lesbian and gay liberation movement, those lines were not, like, hard and fast. So lesbian feminists were active in the reproductive rights movement. Lesbian feminists were key in building the movement against domestic violence and sexual assault. If it wasn’t for lesbians, there would be no movement. But the thing is, a lot of that history is erased.

Um, we really… We were so…. What’s the word? Um, hated. We were so hated and so ostracized, I believe, by our communities of color. There was nothing sane to be heard. Hardly anything sane to be heard about the reality that not everybody is heterosexual in a people of color context anywhere.

EM: What were the kinds of things you’d hear?

BS: I spoke… Howard University used to have national Black writers’ conferences. They sponsored them throughout the ’70s. And I was invited to the last one which they ever had. It was in 1978. I had written “Toward a Black Feminist Criticism” and published that in 1977, and as a result of that, I was invited to speak at that conference. And I was supposed to speak from the essay, where I talk about lesbian this, and lesbian that, and lesbian the other.

It’s such a perfect example of how Black people were dealing with the reality of both gender and sexuality politics. Um, so I was invited to speak. It was on their first panel they’d ever had about Black women writers.

EM: But it wasn’t Black lesbian writers?

BS: No, no. And they wouldn’t even invite any other feminists. I asked them to invite… “Would you please put another feminist on this panel?” And they refused to do that. It was at one of their large auditoriums at Howard. Um, the place was packed. You know maybe 500 people. I read excerpts of “Toward a Black Feminist Criticism.” And then I wrote a few paragraphs that were specifically aimed at the Black community. Not cruel things, by any means. Just interpretive things that would be helpful given that the essay had originally been written for a primarily white and feminist audience. So, you know, I read it, you know, and then I sat down. And all hell broke loose.

EM: Why?

BS: Because they were so upset.

EM: What did you say that upset them?

BS: That lesbians exist and we deserve not to be hated. Oh yeah. Oh no. They went wild. You gotta read the essay. You should read the essay. Because, like, when I tell you how upset they were, you should see what they were responding to. Which was like, “Hey, you know, there’s a Black women’s literary tradition. You know, it’s as strong and long as anybody else’s. And it’s legitimate. And we should use a feminist perspective to look at writing by Black women. There is such a thing as sexism. And the people who are most marginalized in this whole mix are Black lesbians and Black lesbian writers. But yet, we are going to continue and do what we do.”

The first person who got up is a person who is still with us named Frances Cress Welsing. She’s a psychologist. And she’s well-known. She basically said, “Well, you know, I really feel sorry for the sister and, you know, I pity her…”

EM: You?

BS: Yeah. Me! Me! Yeah. “I really feel sorry for her. And feel… And, you know, like, I have pity on you since you can’t be a heterosexual like me. But, you know… But, you know, you have my sympathy.” Whatever. “But, homosexuality will be and is the death of the race.” That was the first statement. “Homosexuality is the death of the race.” And they were off and running. And I was just devastated.

Just to tell you how frightening the atmosphere was there… There was a whole little row of my friends, people had come from Boston, New York… And Audre Lorde was there. Now Audre of course is known as a warrior and the bravest of the brave and what have you. She did not open her mouth. The crowd turned ugly, you know. They were so angry and so frightening.

And, see, Audre being several years older than I—12 years older exactly—um, she had been involved in the Black arts movement of the 1960s and ’70s. And they knew her as, you know, one of their poets. And then when she came out… or at least when they began to reevaluate her as this lesbian, she really paid a high price for that. And I think she was so scarred by that experience… The attack was so visceral and so violent… I can’t think of any other word except for violent, Audre did not open her mouth. And she said to me later that she was sorry that she didn’t say anything or couldn’t.

And when I went to the back of the auditorium when the ordeal was finally over, I saw someone who I vaguely knew. A Black male critic. And I was saying how awful it was. I mean ‘cause… I mean, these are my people. And they are aiming all this hatred at me. And I say to this guy… I was speechless, practically. And I was looking to him for some kind of like, “Oh yeah, it was really rough.” And you know what he said to me? He said, “Well, at least you weren’t lynched.” Black person to Black person. One to another. You know. “Well, at least you weren’t lynched.”

EM: What were some of the other things that people said to you?

BS: I really can’t remember much other than that. But it’s like one of those traumatic experiences that you probably… You can remember the feeling, you don’t necessarily remember the details.

One of things that someone said… I don’t know if I should tell you this. But it flatters me. I like it. She said… I think this was a straight woman. She said… And of course you also have to remember that most of the people there had never heard anything about lesbian and gay reality except for how awful it was, how sinful it was, how sick it was, and how debased it was. But, anyway, this Black woman, who I’ve seen fairly recently, said, “Well, you know, what I remember is just how beautiful you were.” She said, “You know, you were just so beautiful.” And I did look very nice. I made a special effort to look very nice.

EM: Did you? Why was it important for you to look nice that day?

BS: You know, being raised by Black women as I was, you try never to go out looking like you just rolled out of bed or whatever. And it was particularly important—Howard! Howard, the most distinguished Black university in this country. I mean, after all.

It was particularly important, I thought, for me to look well because the stereotype of course is that the reason that one is a lesbian, one of them, is that because you’re so unattractive that no male would want you. And we used to laugh a lot about that and joke about that, you know, in the ’70s when we were all young and gorgeous. Because we would say, “Well, they obviously never been to the bars we’ve been to.” Every woman was more gorgeous than the last.

Not only were we young, but we also had this inner glow of spirit, of spirit released. Because, you know, we were creating something that was just so amazing and magnificent, which was our own way of being in the world. So not only did we have the glamour of youth or the looks of youth, we also had this incredible self-confidence.

EM: Did you ever go back to Howard?

BS: No. Howard… I’ve not spoken at Howard since then. I don’t get invitations from Black institutions, to speak at Black institutions, except for Spelman.

———

EM Narration: The homophobia Barbara encountered at Howard University was hardly an anomaly—and it didn’t end there. In the early 1980s, Black civil rights leaders were making preparations for the 20th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Barbara and the National Coalition of Black Gays—or NCBG—tried to persuade the organizers to invite a gay person to speak at the celebration.

The suggested speakers included James Baldwin, Audre Lorde, and Barbara herself. But despite that impressive short list, NCBG was told there would be no gay speaker. That’s when several gay African American men decided to step in—or rather sit in… at the office of Walter Fauntroy. He was the District of Columbia’s non-voting Congressional representative.

A quick heads-up. I’m not sure what I did back in 2001 when I recorded Barbara’s interview because in the story that follows, the audio quality isn’t up to our usual standards, but it’s a story worth hearing.

———

BS: And they went to his office and they sat in his office. And they were arrested over this issue of whether there was going to be a Black gay or lesbian speaker at that march. And as a result of that sit-in, and those arrests, indeed we did get our speaker. Audre Lorde was the speaker as it turned out. And it was just so ironic. I mean, he was a guy who had been in the civil rights movement, who participated in sit-ins…

EM: Who?

BS: Fauntroy. Yeah. Had been… You know, like this is a tactic that he had used against the white power structure. And then, because of homophobia, it was a tactic that had to be used against him. He made the infamous statement that, as far as he was concerned, that gay rights… He said, “If we had someone speaking about gay rights, then we might as well have someone speak about penguin rights.” Subsequently, like, at gay prides and what have you, there were people who would actually dress up as penguins. To make the point. Gay. Penguins. Whatever. Anyway… That was quite a triumph. But you know that was one piece of work that we did together. And then…

EM: That march was in November of ’83?

BS: Yes. And so then I moved to…

EM: Audre Lorde spoke there?

BS: Yes, she did. Yes, she did. It was incredible. You know it’s like, well, there’s my friend kicking, kicking behind. No. It was an incredible feeling. Just feeling for that moment that at least truth and sanity is being conveyed to a group of people for whom this is news.

EM: And they knew who she was?

BS: I don’t think they knew really who she was. A lot of Black people did not know who she was.

EM: Did they know at the time she spoke that she was a lesbian?

BS: Absolutely. Oh yeah. Oh no. She always told people that up front. She always led with, “I am a Black, lesbian, warrior, mother, cancer survivor here to do my work. Are you doing yours?”

EM: So it was a big, it was a high point…

BS: It was a very, very big deal. It’s a very important piece of Black lesbian and gay history. I mean, my life’s work in the context of LGBT organizing has been to try to raise the level of understanding and to lessen the level of homophobia and sexism in Black contexts. That’s my life’s work.

I think the reason that my politics have remained as steadfast and strong as they have is because I’ve always had a base of women of color, of people of color, to fall back on and to rely upon so that I’m just not just this one crazy voice saying, “Did you ever think about racism and police brutality or poverty and homelessness?”

The ethical framework that I was raised with, some of it through the church, some it just through the people around me who functioned in this way, was that I had responsibility. And also I was to be decent and caring about all in need.

I mean there’s just been this real move to the right in the country in general. And it has affected the lesbian and gay movement, too. You know, “Give me gay marriage, you know, I’ll shut up. I’ll never do anything to disrupt or turn over your little apple cart. I will not mention those other people. They can, you know, like… Whatever iceberg they’re floating on, they can just sink or swim on their own. You know, the poor, the people on welfare, you know, people of color, women. Don’t care about them. You don’t have to be threatened by me. And I’ll even vote Republican if that’s what you’d like me to do.” I mean, a non-movement. Making no connections. You know. Nothing that has revolutionary potential because when all you want is a few reforms given to you by corporate entities and/or by the government, you’re not really talking about fundamental political and social change. You’re not.

EM: Because that comes from where?

BS: That comes from the fervor of people who are the most oppressed, saying, “It has got to be different from now on.” That has been my experience of how movements are built. That’s the spirit of Stonewall. That’s the spirit of the women’s movement. It was the spirit of the anti-slavery movement. It was the spirit of the Black civil rights movement. Nobody in Washington said, “I think Black people really need to be treated better here.” They didn’t say that. They didn’t give a flying F-U-C-K. They did not care.

EM: I want to speak briefly about ’93. You said that ’93 march was difficult to go to. What happened?

BS: Everything has gotten more corporate. And we also had the impression that they wanted people to be presentable. That they wanted to show a really kind of a bland and non-threatening face to middle America.

It wasn’t just about people of color. It was about anything that wasn’t squeaky clean vanilla, you know, sell it on the evening news. And that I find offensive. You know when I talk about the joy of being at those early demonstrations, part of it was just seeing how outrageous people were and could be. And how very lovable they were in that, you know. That included people who were sex radicals. It included people, you know, in drag. It included people who were in, you know, into leather.

It thrilled me in some ways being a girl, having been a girl who was raised in a Midwestern city—albeit Cleveland, you know, which faces East, admittedly—um, coming from definitely a family who had come from the deep South, and being raised in the Black Baptist church, that I could actually be talking to a guy in a dress. And very happy to be doing so. That thrills me. Because it’s about breaking boundaries. It’s about, like, finding what connects you to other people that doesn’t have to do with trappings. You know? That’s a part of what we were fighting for. Even though I myself… I always describe myself as being pretty socially conservative though politically radical because of that background that I just described to you. The only thing I do outrageous is fight for revolution and freedom, you know. But the thing is, in the supermarket, it’s just, you know, there’s the middle-aged Black lady again.

———

EM Narration: In the years after I first met her, Barbara Smith got deeply involved in local politics and helped elect Albany County’s first African American district attorney. That was before she ran for public office herself and won a seat representing her neighborhood on the local Common Council from 2006 to 2013. During her final year in office, she also helped elect the city of Albany’s first female mayor.

In 2014, Barbara and her co-authors, Alethia Jones and Virginia Eubanks, published Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around: Forty Years of Movement Building with Barbara Smith. It’s an account of Barbara’s contributions to Black feminism, Black women’s studies and literary criticism, urban politics, and plenty more.

Recently, Barbara was invited by the New York Times to reflect on life after Stonewall. Her piece was entitled “Why I Left the Mainstream Queer Rights Movement.” In it, Barbara acknowledged that the LGBTQ civil rights movement had made great legislative and social strides, but noted that many in the community continue to struggle. And “Gaining rights for some while ignoring the violation and suffering of others does not lead to justice. At best, it results in privilege.”

After more than four decades as an activist, Barbara is still trying to keep us honest. I think that’s what Audre Lorde would call “doing the work.”

———

Many thanks to everyone who makes Making Gay History possible: senior producer Nahanni Rous, producers Josh Gwynn and Katherine Cook, deputy director Inge De Taeye, audio engineer Jeff Towne, researcher Brian Ferree, photo editor Michael Green, and our social media team, Cristiana Peña, Nick Porter, and Denio Lourenco. Special thanks to Jenna Weiss-Berman and our founding editor and producer, Sara Burningham. Our theme music was composed by Fritz Myers.

Making Gay History is a co-production of Pineapple Street Media, with assistance from the New York Public Library’s Manuscripts and Archives Division and the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Season six of this podcast has been made possible with funding from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, the Calamus Foundation, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, the Small Change Foundation, Irwin and Andra Press, and our listeners, including Ann Northrop. Thanks, Ann!

Stay in touch with Making Gay History by signing up for our newsletter at makinggayhistory.com. Our website is also where you’ll find previous episodes, archival photos, full transcripts, and additional information on each of the people and stories we feature.

So long! Until next time!

###